There was no consensus in Berlin and Rome over where the Allies would strike next. Hitler’s strategic perception was that the Balkans were the most critical to Germany’s military survival, owing to the importance of Romanian oil and the supply of critical raw materials from elsewhere in the region. The Italian and German high commands variously pointed to Sardinia, Sicily, Crete, and Greece as the next Allied objective. This led to a crippling dispersion of the already weakened Axis forces. To amplify this uncertainty, Britain conducted a deception campaign, with Operation Mincemeat as its most brilliant ploy. The body of a dead man was dressed in a British officer’s uniform. A briefcase chained to the corpse contained phony documents addressed to General Sir Harold Alexander describing a forthcoming “Operation Husky” against Greece by General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson’s forces in Egypt, an “Operation Brimstone” by Alexander’s forces against Sardinia, and a deception campaign to convince the Germans that Sicily was the objective. The body was deposited off the Spanish coast by submarine on the night of April 30, 1943, on the presumption that it would wash ashore and be turned over to German officials. This indeed proved to be the case, and copies of the contents of the briefcase arrived in Berlin. Hitler was already inclined to view the Balkans as the main Allied objective and the Mincemeat documents bolstered his preconceptions. Between March 1943 and July 1943, Wehrmacht strength in the Balkans rose from eight to 18 divisions and those in Greece from one to eight; Sicily received barely two divisions. This was not solely attributable to the Mincemeat deception, but rather that Hitler’s previous inclinations had been supported by Mincemeat.

Italian coastal defense doctrine focused on the protection of major ports. The Syracuse-Augusta stronghold was heavily fortified, including the Batteria Opera A on Cape Santa Panagia, which covered both ports. This turreted mount was built during World War I on the pattern of the famous Amalfi battery and was armed with twin Vickers 15in. guns, known in Italian navy service as the 381/40. This battery fired on British warships attempting to land special forces on June 10, but the guns were spiked and the crews retreated on the morning of July 11 before being captured by advancing British forces. (MHI)

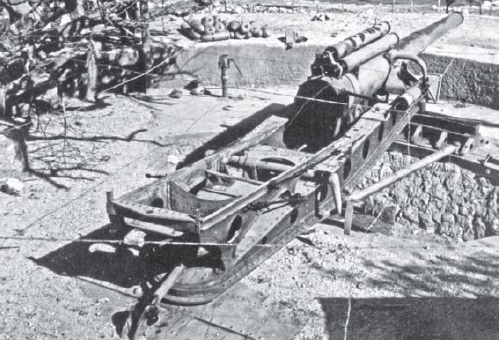

Palermo had extensive coastal fortifications, which offered little defensive value when the US Army approached from landward. This is an Ansaldo 152/45 S.1911, a World War I siege gun built under license from the French Schneider company. It was deployed in the Palermo area for coast defense with two batteries of the army’s 41o Gruppo d’artiglieria pesante. (NARA)

Berlin’s assessment of the situation was not shared by Rome. The Comando Supremo thought that Sardinia was the most likely target for the upcoming Allied operation, owing to its obvious potential as a forward base for the Allies to leapfrog into northern Italy and southern France. Both German and Italian theater commanders were far more concerned about the threat to Sicily. Kesselring and Guzzoni both felt that Sicily was a highly likely objective. The reinforcement of Sicily with two German divisions was a local initiative. The creation of the Division Sizilien was initiated by Baade, and the transfer of the Panzer-Division “Hermann Göring” was initiated by Kesselring with the acquiescence of Berlin. The location of the two divisions was the source of some controversy. Guzzoni wished to have both divisions located in southeastern Sicily owing to his assessment that this was the most likely locale for Allied landings. Kesselring was concerned that the Allies would want one of the western ports such as Palermo or Trapani, and so he ordered 15. Panzergrenadier-Division deployed there.

The real Axis strategic dilemma in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1943 was Italy’s ultimate intention towards the Rome–Berlin alliance and its willingness to continue the war. The German foreign ministry was paying close attention to rumors of King Victor Emmanuel’s disaffection with Mussolini and there was ample evidence of a crisis in the Italian government. By the spring of 1943, a toxic cynicism permeated Italian–German relations. In mid-May 1943, the German general staff completed contingency plans codenamed Alarich and Konstantin on Hitler’s instructions. Operation Alarich, named appropriately enough after the sack of Rome by Goth invaders in ad 410, was entrusted to Erwin Rommel. The plan was to infiltrate four German divisions into Italy, followed by a dozen more divisions, to take over control of Italy. Operation Konstantin was a related scheme to disarm Italian forces in the Balkans in the event that Italy switched sides.

The threat posed by Allied airborne operations prompted the Italian army to form special anti-paratrooper units (NAP: Nuclei antiparacadutisti), usually relying on truck-mounted infantry. This is an Autocarro unificato Fiat 626 fitted with a Bredo 20mm mod. 35 in the rear-bed. (MHI)

On June 21, 1943, the Italians presented the Germans with a long list of weapons they needed to continue the war. At the same time, the Italian army was adamant that a strict limit be placed on the number of German divisions allowed into Italy for fear they would be used to impose a new government subservient to Germany. Berlin regarded the extravagant weapons demand, and the likely German refusal, as an Italian pretext for giving up on the war. The mistrust on both sides was entirely justified; the Italian government was plotting ways to extract itself from the war and the Germans were plotting to take control of Italy.

In the wake of the Casablanca conference, the Allies created the Force 141 headquarters in the suburbs of Algiers to formulate the Operation Husky plan. Its first “Tactical Appreciation” was released on March 15, but received little attention from senior Allied tactical commanders, who were focused on the conclusion of the Tunisian campaign. The two predominant tactical considerations in the plans were airfields and ports. Tedder and the other air chiefs insisted that the operation needed to seize airfields as soon as possible. The bases on Malta were already beyond their capacity and Sicily was on the outer edge of the range of many of the fighters such as Spitfires. Sicilian airbases would immeasurably aid in achieving air dominance over the island. The navy chiefs wanted the planners to focus on the need for port facilities to supply the army units once the landings had taken place. The best port on Sicily was Messina, with a daily capacity of 4,000–5,000 tons, but this objective was ruled out immediately since it was so heavily fortified and beyond the range of fighters based on Malta. The next best port on Sicily was Palermo on the north coast, while Catania and Syracuse on the east coast could each handle more than 1,000 tons of cargo per day.

The original plans for Operation Husky attempted to meld the airbase and port requirements into a complicated scheme of sequential landings. The British Eastern Task Force would conduct four separate landings on D-Day to capture airfields and smaller ports, followed by a main landing on D+3 against Catania. The American Western Task Force would begin its landings on D+2 to capture the airfields at Sciacca and Castelvetrano, followed by D+5 landings on either side of Palermo to capture the port. This scheme immediately ran into opposition since it was overly complex and would lead to a dispersion of Allied forces. Eisenhower suggested a concentration of landings in the southeast, but at first this was rejected owing to the need for the port of Palermo in the northwest. By the end of March 1943, Montgomery became involved in the planning, and he was very critical of the weakness of the British landings in the southeast. One option would be to use one of the American divisions from the Western Task Force to seize Gela on the western side of the British beachheads.

By late April, the naval commanders were becoming increasingly worried about the threat of Axis airpower against the invasion fleet after reading the alarming intelligence assessments, and so more supportive of Tedder’s push for capturing airfields. British corps commander Lt. Gen. Oliver Leese suggested abandoning the multi-pronged concept in favor of a unified attack against the southeast corner of Sicily. With its cluster of airbases and proximity to the ports of Syracuse, Augusta, and Catania, this area became more and more attractive as the central focus of Allied operations. Nevertheless, the conference again deadlocked, forcing Eisenhower to convene yet another conference on May 2. This time, Montgomery personally made a strong case for the unified approach, which was supported by both Eisenhower and Alexander, ending the debate. Neither Patton nor Bradley was entirely happy with the plan since the Seventh US Army no longer had a major objective beyond acting as a flank guard for the British 8th Army. On the other hand, neither was inclined to make a strenuous protest, recognizing that, in Bradley’s words, the whole planning process had taken place “in a fog of indecision, confusion, and conflicting plans.” Now at least, a degree of unanimity had finally prevailed.

The May 19 Husky plan was primarily focused on the initial landings and the rapid seizure of airfields near the landing area. The next phase of the land campaign was concentrated in the British sector, with an aim to capture the ports of Augusta and Catania, as well as the airfield complex around Gerbini. The final phase of the campaign, “the reduction of the island” was not tightly defined in terms of objectives or focus and this would be the root of later difficulties.

One of the most useful technical innovations that saw its debut during Operation Husky was the DUKW amphibious 2½-ton truck. This not only provided the capability to move supplies ashore like conventional landing craft, but also, on reaching the shoreline, the DUKW could continue to its destination beyond the beachhead, greatly simplifying logistics, and helping to reduce the usual congestion in the beachhead. This DUKW is moving through Port Empedocle on July 25, 1943. (NARA)