5

ON SEPTEMBER 29, 2000

The assertion by Alan Dershowitz, that the Bostonian “provocateurs” got what they deserved from the occupying forces of the British empire on the night of the Boston Massacre, would be little more than a minor nuisance to the revolutionary history of the United States if it hadn’t foreshadowed the Harvard law professor’s far more serious infidelity toward the great achievement of the American Revolution—the Bill of Rights. How did it come to pass that Dershowitz, who once described the Bill of Rights as “our most precious national resource,” and who opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam, would devise a jurisprudence for a counterterrorist “preventive state” that would maximize the police, military, and surveillance powers of the United States?

The answer can be found to a good extent in Dershowitz’s writings about the Israel-Palestine conflict—which has been the predominant focus of his work since the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States—and in his views in that context on state power and terrorism. Indeed, Dershowitz wrote his 2006 manifesto of the counterterrorist preventive state, Preemption, in his capacity as Israel’s chief public defender in the United States. Dershowitz, in effect, touted that role himself with the prosecution/defense format of his 2003 book The Case for Israel, with Dershowitz pleading the defense case for Israel in response to the work of Noam Chomsky, Edward Said, and other critics of Israel. And the point of Preemption was to lay out his Israel-influenced jurisprudence for preventing terrorism and to recommend it for adoption by the United States and other Western democracies. However, the argument here is that Dershowitz’s defense of Israel’s Mideast policies, and the development of a jurisprudence of prevention derived largely from the counterterrorist practices of the Israeli government, should not be viewed as transferrable to the United States, given that the Dershowitz-made law derived from Israel clashes fundamentally with human rights abroad and long-standing American liberties at home. The purpose of this chapter is to present a case study of these claims by looking at how Dershowitz depicted the events that occurred before and after September 29, 2000, and how that depiction influences the terrorism-prevention jurisprudence that he seeks to apply to the United States.

Longtime U.S. presidential advisor Dennis Ross, in his 2004 book The Missing Peace: The Inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace, provides one of the most detailed accounts of events that began in earnest with the Camp David summit in July 2000—involving Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, Palestinian chairman Yasser Arafat, and President Clinton—the failure of which led to the start a few months later of the Second Palestinian Intifada1 on September 29, 2000. Ross’s account of events is of special interest here, not only because he was the chief U.S. negotiator under the Clinton administration for the Israeli-Palestinian talks, but also because he is a major source in Dershowitz’s own books and articles about the important events that occurred during those last several months of Bill Clinton’s presidency.

One page before describing the events that led to the course-changing confrontation of September 28–29 at the Haram al-Sharif / Temple Mount in the Old City in East Jerusalem, Ross reported that he had personally lobbied Israeli and Palestinian government officials in Washington a few days earlier to continue the talks that had broken down during the Camp David summit in July. Ross noted that just before the negotiators arrived, “Arafat visited Barak at his home” in Israel and that “both sides reported that the meeting was very warm.”2 In his 2008 book The Much Too Promised Land, Aaron Miller, a U.S. negotiator at Camp David on Ross’s team, reported that “in late September [2000], before the outbreak of the second intifada, [Barak] would have his best meeting with Arafat ever, and negotiations continued.”3 Ross also reported that Barak and Arafat “called President Clinton before concluding their evening, with Barak telling the President, ‘I will be a better partner with the Chairman [Arafat] than even [former Israeli prime minister] Rabin.’” About the cordiality, Ross wrote that “it was in this seemingly hopeful setting that the negotiators arrived for three days of discussions” starting September 26, 2000. Ross also wrote that “little did I know that these three days [September 26–28] would mark probably the highest hopes for peace during my tenure—and that a descent into chaos and violence would soon follow.”4 Given these accounts, it is likely that neither Barak nor Arafat expected what was about to break out on September 29.

Indeed, looking back, Ross wrote: “At the time, there was one development that Palestinians say transformed everything: Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Haram al-Sharif / Temple Mount. Sharon, the leader of the Likud opposition, visited the Temple Mount on September 28 with a large contingent of Israeli police providing security for him: both Likud Party politics and his desire to demonstrate that the Barak government could not surrender this sacred ground [in negotiations with the Palestinians] prompted his visit.” Ross also revealed that on September 27, Saeb Erekat, a Palestinian negotiator, approached Ross during the negotiations in Washington with “a personal request from Arafat: Might I [Ross] be able to use [U.S.] influence to stop Sharon from going to the Haram Al-Sharif [Temple Mount] the next day?” Ross turned down Arafat’s request, explaining: “I told Saeb that if we were to ask Sharon not to go, he would seize the U.S. request to make political hay with his right-wing base; he would castigate us and say he would not give in to pressure from any source—including the United States—on Israel’s right to the Temple Mount.”5

Thus, with Barak’s acquiescence and no opposition from the United States, on September 28 Likud Party leader Sharon went to the Temple Mount in the Old City in the heart of Arab East Jerusalem, which Israel had annexed in 1967 immediately, and illegally, after its pivotal triumph in the Six-Day War.6 The issue of which side rightfully claims sovereignty over the Old City and East Jerusalem is one of the most contentious issues of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

In an article with the headline “Sharon Touches a Nerve, and Jerusalem Explodes” and a dateline of September 28, the New York Times’ Joel Greenberg reported the events at the Temple Mount pursuant to Sharon’s visit: “Tightly guarded by an Israeli security cordon, Ariel Sharon, the right-wing Israeli opposition leader, led a group of Israeli legislators onto the bitterly contested Temple Mount today to assert Jewish claims there, setting off a stone-throwing clash that left several Palestinians and more than two dozen policemen injured. The violence spread later to the streets of East Jerusalem and to the West Bank town of Ramallah, where six Palestinians were reportedly hurt as Israeli soldiers fired rubber-coated bullets and protestors hurled rocks and bottles.”7

On September 30 (with a September 29 dateline), the Times reported:

Violence erupted in the sacred, contested center of Jerusalem’s Old City today as stones and bullets interrupted a day of prayer for Muslims and Jews, turning it bloody. Four Palestinians were killed at Haram al-Sharif, known to Jews as Temple Mount, in a second day of rioting that began when Ariel Sharon, the rightist opposition leader, visited the Muslim compound on Thursday to assert Jewish claims to the site. Wearing full riot gear, Israeli police officers today stormed the Muslim area, where they rarely set foot, to disperse Palestinian youths who emerged from Friday prayer service to stone first a police post at the Moghrabi Gate and then Jewish worshippers at the Western Wall.8

On October 1 (September 30 dateline), the Times reported on the escalating violence: “Violent clashes between Palestinians and Israeli troops left at least 12 Palestinians dead and hundreds wounded in the third day of fierce fighting set off by the defiant visit on Thursday of a right-wing Israeli leader, Ariel Sharon, to the steps of the ancient mosques atop Jerusalem’s Old City. . . .The Israeli military said tonight that seven Israeli soldiers had been lightly wounded by rocks in the disturbances today. At least 16 Palestinians have been killed and hundreds injured in the last three days.”9 Thus, up to this point, only Palestinians had been killed (“at least 16”), with no fatalities among Israelis.

On October 2 (October 1 dateline), the Times noted that “nine Palestinians were reported dead today, bringing the Arab death toll to 28 since Friday” (September 29). The Times also noted that “the riots claimed their first Israeli victim today, a border policeman fatally wounded during a gun battle that began when Palestinians surrounded Joseph’s Tomb, a holy Jewish site, in Palestinian controlled Nablus.”10 In an article in the same edition, and in dramatic contrast to the optimism of September 26–28, the Times’ Jane Perlez wrote about the implications of the Palestinian rioting and the harsh Israeli response:

With the outbreak of the last four days of violence, the prospect that President Clinton can broker an end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict before he leaves office has all but evaporated, diplomats and other experts said today. . . . Several experts pronounced the peace effort virtually dead, at least for the rest of Mr. Clinton’s administration, largely because of the time it would take to reinvigorate a process that was already deadlocked over the future status of the Old City of Jerusalem, the very place that prompted the violence. In addition, the violence and the loss of trust it has generated may further undercut the peacemaking efforts of Prime Minister Ehud Barak of Israel, who was already in a weakened political position. And the clashes may also make it more difficult for the Palestinian leader, Yasir Arafat, to deliver the concessions that the administration has been looking for him to make.11

Thus, the prospects for a comprehensive peace agreement went from a day (September 26, 2000) that marked “probably the highest hopes for peace during my tenure” (Ross) to only a few days later, when the peace process “has all but evaporated” (Perlez) following Ariel Sharon’s provocative visit to the Haram al-Sharif / Temple Mount on September 28, the stone-throwing Palestinian uprising on September 29 in response to Sharon’s visit, and a post–September 29 casualty count of twenty-eight Palestinian fatalities and one Israeli soldier.

Indeed, the next day, October 3, the Times reported that “Prime Minister Ehud Barak of Israel said on Monday [October 2] that peace talks were now ‘on the shelf’ and Yasir Arafat called for an emergency Arab summit meeting as violence tore through Israel and the Palestinian territories for the fifth straight day.”12 Also on October 3, the Times’ Deborah Sontag wrote about the purpose of Sharon’s September 28 visit to the Temple Mount:

What was Mr. Sharon’s motive? Mr. Sharon maintained that it was just an ordinary visit by an Israeli to what Jews call Temple Mount, above the remains of the First and Second Temples—among the holiest sites of Islam, the holiest of Judaism. Many Israelis applauded him for this, whatever the consequences. Political experts [in Israel], however, widely speculated that Mr. Sharon was trying to steal the spotlight from Mr. [Benjamin] Netanyahu, his rival for leadership of the right wing, on the day after corruption charges against Mr. Netanyahu were dropped. Additionally and more significantly, Mr. Sharon, an old-time hard-liner, was seen to be making a deliberate nationalist statement, well aware of its potential both to hijack the peace efforts and to undermine Mr. Barak.13

Thus, at this key juncture in the peace negotiations, it was the Israeli domestic political situation, and the actions of Israeli political leaders, that accounted for the breakdown of negotiations, rather than any secret plan by Yasir Arafat, as Dershowitz has charged (see further on), to sabotage the negotiations by launching a terrorist campaign on September 29, 2000, against Israel.

With respect to Palestinian casualties, on October 4, the Times’ William A. Orme Jr., upon interviewing Dr. Khaled Qurie, “the director of East Jerusalem’s busiest hospital,” reported the doctor’s observation pertaining to “the high number of upper body injuries” that were sustained among the thirty-five Palestinians who had been admitted to Makassed Hospital on September 29 alone. Orme noted that “Israeli soldiers are taught to fire the coated [‘rubber bullet’] projectiles from specially adapted M-16s from at least 100 feet away and only at the feet and legs.” However, he reported: “But there are many documented instances of close-range shootings at eye level: since Friday [September 29] doctors at St. John’s Eye Hospital in Jerusalem have treated 18 Palestinians who were shot in the eye with rubber projectiles.” Most of the damaged eyes “were left sightless,” said Michael Cook, the chief executive there. Orme then reported:

Israel’s critics, backed by the European Union, are calling for an international inquest into the casualties. At least 42 Palestinians have been killed in the clashes, including 13 children. And for the first time since peace talks led to the creation of the Palestinian Authority six years ago, Israelis have fired on civilians from helicopter gunships using armor-piercing missiles. To the dismay of Israeli officials, the United States has joined in the criticism. At the United Nations Security Council meeting in New York today, the United States provisionally agreed to a draft statement condemning Israel for “the acts of provocation, the violence, and the excessive use of deadly force against Palestinian civilians in the past few days.”14

On October 7, with the United States abstaining, the UN Security Council passed a resolution that “deplore[d] the provocation carried out at Al-Haram Al-Sharif [Temple Mount] in East Jerusalem on 28 September 2000, and the subsequent violence there and at other Holy Places, as well as in other areas throughout the territories occupied by Israel since 1967, resulting in over 80 Palestinian deaths and many other casualties.” The resolution “condemn[ed] acts of violence, especially the excessive use of force against Palestinians, resulting in injury and loss of human life.”15

To summarize events within the twelve-day period of September 26 to October 7: The lead U.S. negotiator, Dennis Ross, described an atmosphere of optimism among Israeli and Palestinian negotiators just prior to and during a three-day round of informal peace talks in Washington on September 26–28; Sharon’s visit of September 28 to the Haram al-Sharif / Temple Mount was probably designed to be deliberately inflammatory and obstructive to the peace negotiations; the New York Times reported in its day-to-day coverage that Israel had employed nearly all of the deadly force on and immediately after September 29, with nearly all of the fatalities being Palestinian; and that the Israel-Palestine peace process under the auspices of the Clinton administration was seriously threatened as a direct consequence of this chain of events. While this narration of events would not seem to point toward a plot orchestrated by Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat to sabotage peace negotiations, or to the onset of Palestinian terrorism against Israeli civilians, that is how Dershowitz has unambiguously constructed these events in his books, newspaper articles, and public speeches since September 2000.

In probably his most influential book about the Israel-Palestine conflict, The Case for Israel, published in 2003, and while seamlessly welding the time framework of the Camp David summit in July 2000 to the Taba talks of January 2001, and thus opportunistically mashing together a highly differentiated sequence of events, Dershowitz observed in the introduction: “I decided to write this book after closely following the Camp David–Taba peace negotiations of 2000–2001, then watching as so many people throughout the world turned viciously against Israel when the negotiations failed and the Palestinians turned once again to terrorism.” Similarly, and also in the introduction, Dershowitz wrote that in response to “Barak’s generous offer [in July 2000], Arafat decided to make his counteroffer in the form of suicide bombings and escalating violence,” and that “the [Palestinian] excuse for the escalation of suicide bombings was Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount.”16 Although these statements apparently have no factual basis, such statements are a staple in Dershowitz’s books and articles about this juncture in Israel-Palestine relations.

Dershowitz then explained why the world “turned against Israel” after the failed peace negotiations and the start of the Palestinian Intifada:

The answer comes in two parts. The first is rather obvious: Arafat played the tried-and-true terrorism card that had worked for him so many times over his long and tortuous career as a terrorist diplomat. By targeting Israel’s civilians—children on school buses, pregnant women in shopping malls, teenagers at a discotheque, families at a Passover Seder, university students in a cafeteria—Arafat knew he could get Israel to overreact, first by electing a more hawkish prime minister to replace the dovish Ehud Barak, then by provoking the [Israeli] military to take actions that would inevitably result in the deaths of Palestinian civilians.17

In his sequel The Case for Peace: How the Arab-Israeli Conflict Can Be Resolved, published in 2005, Dershowitz repeated the claim that Arafat had ordered a terrorist campaign following the failure of the peace negotiations: “A leadership willing to use violence rather than settle for 95 percent of the loaf [the West Bank] is not a leadership really interested in peace. This was demonstrated by Yasser Arafat at Camp David and Taba in 2000 and 2001.”18 Dershowitz repeated the same claim elsewhere in his book, including “after Israel made momentous concessions at Camp David and Taba and Arafat rejected those concessions,” Arafat “opened the floodgates of suicide terrorism.”19

All of this follows his 2002 assessment in Why Terrorism Works: Understanding the Threat, Responding to the Challenge:

In light of the success of terrorism as a tactic, it should come as no surprise that Arafat would once again play the terrorism card after walking away from the Camp David negotiations in 2000, when Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak’s government, with the support of the Clinton administration, had offered the Palestinians nearly everything they were seeking. Rather than trying to negotiate some additional concessions—or compromising their maximalist claims—the Palestinians reverted to the terrorist tactics that had brought them so far already. These included the renewal of the intifada of the late 1980s—only this time featuring much more deadly violence against Israeli civilians than before.20

Although Dershowitz repeats this rendition of events ad nauseam in his published writings, as far as I can tell there is no discernible factual basis for it in the documentary record.

Even more to the point is the detailed chronology of post–September 28 deadly fire by Israelis and Palestinians. Recall that Dershowitz wrote that “by targeting Israel’s civilians [with terrorism] . . . Arafat knew he could get Israel to overreact, first by electing a more hawkish prime minister to replace the dovish Ehud Barak, then by provoking the military to take actions that would inevitably result in the deaths of Palestinian civilians.” However, the election to which Dershowitz refers—in which the right-wing Ariel Sharon became Israel’s prime minister by defeating Ehud Barak—took place on February 6, 2001.21 Yet the first Palestinian terrorist attack inside Israel during this period did not occur until October 28, 2001, according to a document titled “Major Terrorist Attacks in Israel” issued by the U.S.-based Anti-Defamation League.22 The ADL’s chronology of terrorist attacks inside Israel following the events of September 28–29, 2000 is corroborated by numerous reports by the major human rights organizations and the United Nations—none of which support Dershowitz’s claim that it was the Palestinians who initiated lethal violence after Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount on September 28, 2000.

In its first public statement on the events of September 28–29, 2000, an Amnesty International press release dated October 2 stated:

Amnesty International condemned indiscriminate killings of civilians following four days of clashes in Israel and the Occupied Territories which have left at least 35 Palestinian civilians dead and hundreds of others injured. “The dead civilians, among them young children, include those uninvolved in the conflict and seeking safety,” the human rights organization said. “The loss of civilian life is devastating and this is compounded by the fact that many appear to have been killed or injured as a result of the use of excessive or indiscriminate force.” “Israeli security forces appear to have used indiscriminate lethal force on many occasions when their lives were not in danger,” Amnesty International said. “We have been saying for years that Israel is killing civilians unlawfully by firing at them during demonstrations and riots.”23

One week later, on October 9, Amnesty issued another press release, this one about the findings of a three-person delegation that the human rights organization had sent to investigate the circumstances of the killings:24

“Since 29 September, Israeli security forces have frequently used excessive force on demonstrators when lives were not in immediate danger,” Amnesty International said today. In preliminary conclusions from Amnesty International’s delegation in Israel and the Occupied Territories the human rights organization reiterated its condemnation of the excessive use of force by law enforcement officials. “In many cases the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), the Israel Police and the Border Police have apparently breached their own internal regulations on the use of force, as well as international human rights standards on the use of force and firearms,” Amnesty International said. More than 80 people, including children, nearly all of them Palestinians from the Occupied Territories and Israel, have died since clashes began on 29 September 2000 between Israeli security forces and Palestinian demonstrators all over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, as well as in Israel.25

In a report issued in October 2000, and following a fact-finding investigation that it conducted into the unlawful use of force in Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, Human Rights Watch issued the following assessment:

[Human Rights Watch] found a pattern of repeated Israeli use of excessive lethal force during clashes between its security forces and Palestinian demonstrators in situations where demonstrators were unarmed and posed no threat of death or serious injury to the security forces or to others. In cases that Human Rights Watch investigated where gunfire by Palestinian security forces or armed protestors was a factor, use of lethal force by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) was indiscriminate and not directed at the source of the threat, in violation of international law enforcement standards. In Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, the IDF regularly used rubber bullets and plastic-coated metal bullets as well as live ammunition in an excessive or indiscriminate manner. A particularly egregious example of such unlawful fire is the IDF’s use of medium-caliber bullets against unarmed demonstrators in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and in some instances, such as the Netzarim Junction in the Gaza Strip, against medical personnel. These military weapons, which inflict massive trauma when striking flesh, are normally used to penetrate concrete and are not appropriate for crowd control.26

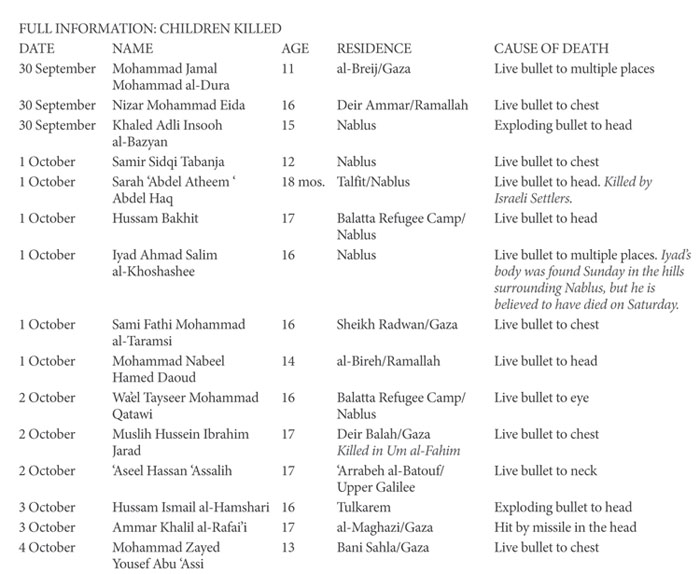

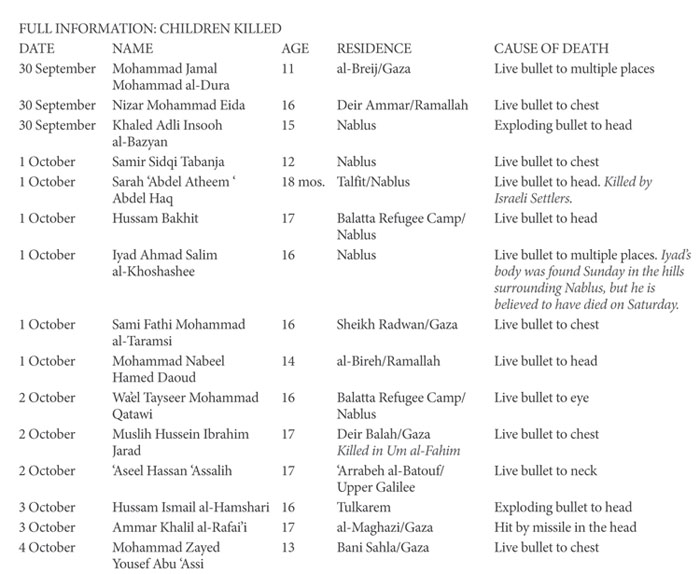

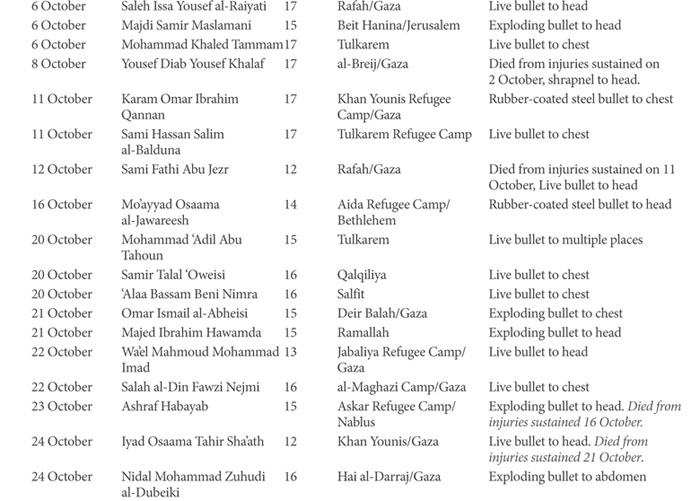

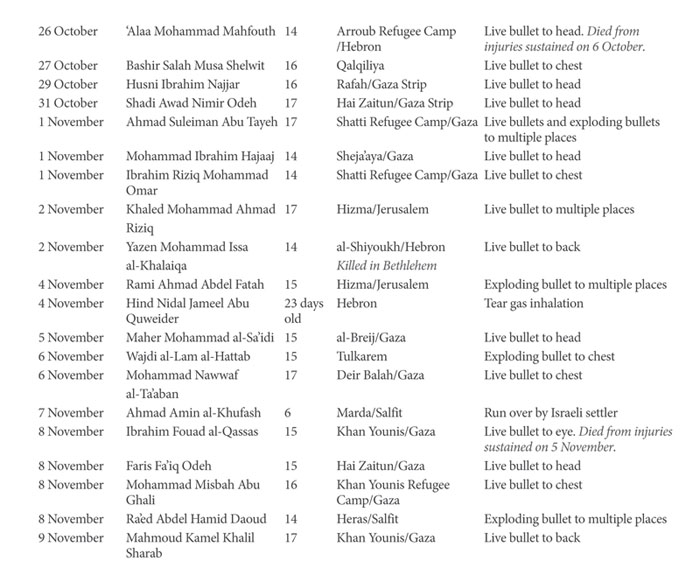

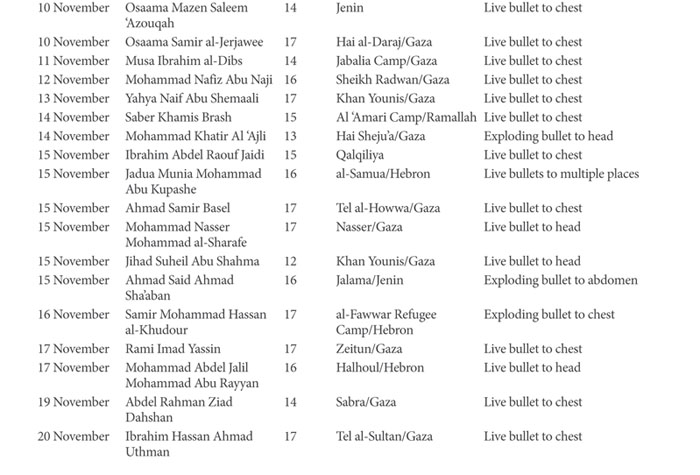

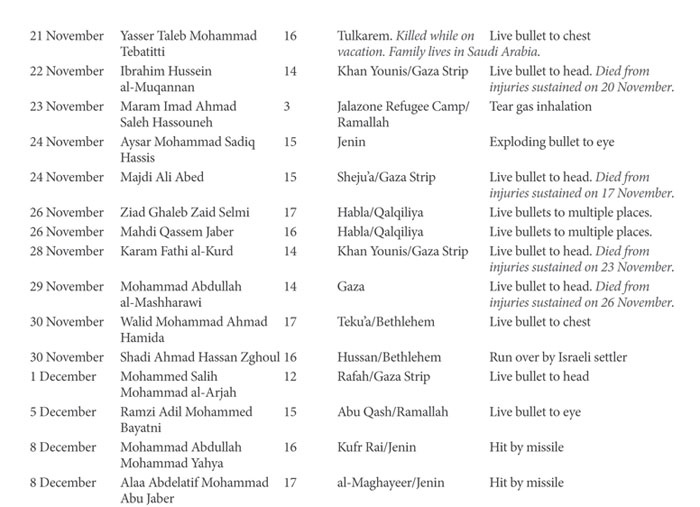

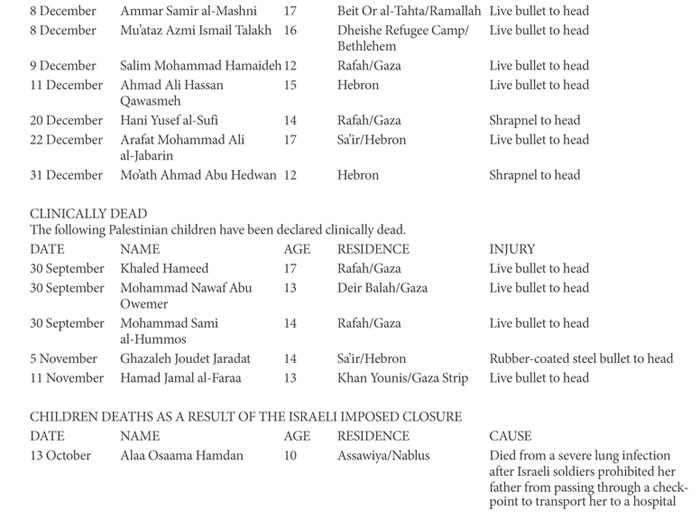

In a report issued on December 31, 2000, Defence for Children International, a Switzerland-based independent NGO founded in 1979, the International Year of the Child,27 published a detailed list, reproduced here, of the names of Palestinian children “who were killed as a direct result of Israeli military and settler presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territories” from September 29 to December 31, 2000.28

This compilation of fatalities is corroborated by other human rights organizations. In a report that was issued in March 2001, Giorgio Giacomelli, the UN’s Special Rapporteur to the Commission on Human Rights, wrote: “From 29 September to end of February 2001, Israeli settlers and soldiers killed approximately 145 Palestinian children under 18, of whom at least 59 were under 15 years of age. An overwhelming 72 percent of child deaths have resulted from gunshot wounds in the upper body (head and chest), which may indicate a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy.”29 Also in March 2001, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in a report authored by John Dugard of South Africa, Richard Falk of the United States, and Kamal Hossain of Bangladesh, following a visit to the occupied Palestinian territories and Israel on February 10–18, 2001, and citing “conservative estimates,” reported that from September 29, 2000, to February 21, 2001, “84 Palestinian children under the age of 17 years have been killed and some 5,000 injured; 1 Israeli child has been killed and 15 injured.” Overall, the authors of the report found that, since the beginning of the Palestinian Intifada on September 29, 2000, “311 Palestinians (civilians and security forces) have been killed by Israeli security forces and civilians in the OPT [Occupied Palestinian Territories],” and that “47 Israelis (civilians and security forces) have been killed by Palestinian civilians and security forces,” while “11,575 Palestinians and 466 Israelis have been injured.”30

One could continue to quote likewise from such reports, with similar results, including those issued a year or more after the start of the Palestinian uprising. For example, in October 2001, John Dugard, then the Special Rapporteur to the UN Commission on Human Rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, issued an assessment of the violence following the events of September 28–29, 2000: “The first few months of the second intifada were characterized by violent clashes between Palestinian protestors, whose weapons were stones and Molotov cocktails, and the Israel Defense Force. Most deaths and injuries were the result of gunfire from the Israel Defense Forces.”31

In summary, there is no discernible basis to support the assertions by Dershowitz that when the peace negotiations in 2000 failed, “the Palestinians turned once again to terrorism,” or, more specifically, that Arafat had targeted Israeli civilians with terrorism in order to “get Israel to overreact, first by electing a more hawkish prime minister” (Ariel Sharon), “then by provoking the [Israeli] military to take actions that would inevitably result in the deaths of Palestinian civilians.”32

That the Palestinians had not resorted to lethal violence against Israeli civilians either on September 29, 2000, or for many months afterward, undermines only one count of Dershowitz’s two-count indictment of Yasser Arafat and the Palestinians. Recall Dershowitz’s claim that “after Israel made momentous concessions at Camp David and Taba . . . Arafat rejected those concesssions.”33 To assess the credibility of this claim, one must review the details of what was presented to the Palestinians (a) at Camp David, Maryland, in July 2000; (b) at Washington, DC, September 26–28, 2000; (c) at the White House on December 23, 2000; and (d) at the Egyptian resort city of Taba on the northern coast of the Gulf of Aqaba in late January 2001.

Camp David, July 11–25, 2000. While a number of commentators have written about the proposals that were tabled at the Camp David summit attended by Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak and President Bill Clinton,34 Dershowitz relies heavily on Dennis Ross and his book The Missing Peace. For example, in The Case for Israel, Dershowitz wrote, again resorting to ambiguous and nonspecific assertions, in this case concerning “Barak’s offer” and “Israel’s offer”:

Virtually everyone who played any role in the Camp David–Taba peace process now places the entire blame for its failure on Arafat’s decision to turn down Barak’s offer. President Clinton, who was furious at Arafat and has called him a liar, has blamed the failure completely on Arafat. Dennis Ross, who was the chief U.S. negotiator, has said that Arafat was unwilling to accept any peace proposal, because for Arafat “to end the conflict is to end himself.” The best proof of Ross’s point is that Arafat did not even offer a counterproposal to Israel’s offer. He simply rejected it and ordered preparation for renewed terrorism.35

Since Dershowitz cites Ross as his most authoritative source about what happened at Camp David in July 2000, it seems appropriate to quickly review how Ross himself represented what the Israelis and Americans presented to the Palestinians as a final-status peace agreement.36

On July 15, Day 5 of the Camp David summit, Barak presented his opening proposals, including a map of the West Bank that, according to Ross, “showed three different colors—brown for the Palestinian state, orange for the areas the Israelis would annex, and red for transitional areas,” which depicted a 14 percent Israeli annexation of the West Bank, including “orange areas in the Jordan Valley and in the corridor from Jerusalem to Jericho,” thus depicting a corridor of Israel-annexed Palestinian land not only along the east border of the West Bank, but another corridor of Israel-annexed land that severed the bottom third of the West Bank from the top two-thirds.37 At Camp David, according to Ross, Barak later proposed Israeli annexation of 10.5 percent of the West Bank, leaving 89.5 percent to the Palestinians (Day 6),38 Israeli annexation of 11.3 percent of the West Bank, leaving 88.7 percent to the Palestinians (Day 7),39 and Israeli annexation reportedly of 9 percent of the West Bank (with a 1 percent swap of unspecified Israeli territory), leaving a net 92 percent of the West Bank to the Palestinians (Day 8).40 This is very different from what Dershowitz described in his nonspecific claims about “Barak’s offer” and “Israel’s offer.”

Furthermore, it is curiously unclear in Ross’s book whether Israel ever withdrew its proposal to dissect the West Bank—with a west-to-east corridor of Israel-annexed West Bank land from Jerusalem to Jericho, connected to the north-south corridor of Israel-annexed land along the Jordan River—since Ross cited the proposed Jerusalem-to-Jericho corridor in his Day 5 account of the Camp David negotiations, without revisiting the status of that detail again in his book.

Washington, DC, September 26–28, 2000. After the breakdown of negotiations at Camp David in July 2000, the chief negotiators met two months later in Washington. One question at issue during this round of meetings was whether the Clinton administration would present a comprehensive peace plan to the Israeli and Palestinian delegations at some point. (The administration formally presented no such plan at Camp David in July.) Although Ross told the negotiators that it was up to the president to decide whether he would issue such a proposal, Ross nevertheless gave each side “a sense of [the U.S.] direction on each issue”:

On borders, I [Ross] said our proposal would be less than 9 percent [Israeli] annexation discussed at Camp David, but would be closer to that 9 percent [annexation] than to the 2 percent [annexation] the Palestinians had countered with at that time; on [territorial] swaps, I said we would offer more than at Camp David but the swap would neither be equal to the Israeli annexation nor large; on security, I told each [delegation] that the Dahlan [Palestinian negotiator] approach was serious, but the [Israeli] right of reentry [of military forces into the newly created Palestinian state] in clearly defined emergencies was important; on refugees, I said there would be no right of return [of Palestinian refugees] to Israel.41

The White House, December 23, 2000. In December, President Clinton and his advisers had decided to present a set of “ideas” or “parameters” for a comprehensive Israeli-Palestinian peace. Clinton declined to present his parameters in writing, and no publicly issued official draft exists of what the president put forward. Rather, Clinton recited the parameters verbally at the White House to the Israeli and Palestinian delegations. In The Missing Peace, Ross itemized the Clinton parameters as follows:

Thus, according to Ross’s summary of the Clinton parameters, the United States had offered the Palestinians the following: (a) a state that would permit Israel to annex—that is, incorporate into Israel’s territorial and legal dominion—4 to 6 percent of West Bank territory for the benefit of 80 percent of Israel’s West Bank settlers, with “a range of 1 to 3 percent swap” of Israeli territory in return; (b) three “early warning” Israeli military facilities located permanently in the West Bank; (c) a “nonmilitarized” Palestinian state that would be required to allow Israeli military forces to enter West Bank territory during “emergencies” declared by Israel at its discretion; and (d) Palestinian sovereignty over Palestinian airspace that nevertheless would have to accommodate Israeli military “training” and “operational” needs.

Clinton also presented his parameters to both parties as nonnegotiable. Yet, it appears that Israel was permitted to modify the Clinton parameters, which already were favorably disposed toward it, by “accepting” the parameters with “twenty pages of reservations,” as Jimmy Carter reported.43 On this count, Ross wrote: “On the twenty-seventh [of December], Barak convened his security cabinet in Jerusalem and they voted to accept the Clinton ideas with reservations. But the reservations were within the parameters, not outside them.”44 Ross provided no additional details. However, as Jeremy Pressman observed in a detailed review of Ross’s book in Boston Review: “Barak had the Israeli cabinet approve the Clinton plan and then, in a separate time and place, presented Clinton with its own list of reservations,” and “in January 2001 Barak publicly rejected the Clinton plan’s call for Palestinian sovereignty over the Haram al-Sharif, the Noble Sanctuary.”45

Yet, when Arafat sought “clarifications” about the Clinton parameters, as one might imagine in the absence of a formal written draft and, for example, about Palestinian “sovereignty” over its airspace and borders that nevertheless must accede to Israel’s “security needs” inside the West Bank, Ross wrote: “Arafat was never good at facing moments of truth. They tended by definition to close doors, to foreclose options. Now, especially with the end of the conflict as part of the President’s ideas, he was on the spot. Almost immediately he looked for ways to avoid an early decision. He wanted clarifications.” Or, as Ross also reported: “Arafat was not up for peacemaking” due to “his rejection of the most basic elements of the Israeli security needs, and his dismissal of our refugee formula.”46 In his book, Ross’s account of the negotiations essentially ends with his account of the Clinton parameters of late December 2000, after which he devoted only one brief paragraph to the Taba round in January 2001.47

Apart from Ross, Dershowitz also relied to a good extent on an article published in March 2003 in the New Yorker titled “The Prince: How the Saudi Ambassador Became Washington’s Indispensable Operator,” by Elsa Walsh. However, while citing the December 2000 Clinton parameters and Bandar’s talk with Arafat on January 2, Walsh provided few details concerning the actual negotiations and seemed at times to be ill-informed about their most fundamental aspects. For example, she wrote:

Clinton, who continued to apply his considerable energy to finding a Middle East solution, came to believe, in December of 2000, that he had finally found a formula for peace; he asked once more for Bandar’s help. Bandar’s first reaction was not to get involved; the Syrian summit had failed, and talks between Barak and Arafat at Camp David, in July, had collapsed. But when Dennis Ross showed Bandar the President’s talking papers Bandar recognized that in its newest iteration the peace plan was a remarkable development. It gave Arafat almost everything he wanted, including the return of about ninety-seven per cent of the land of the occupied territories; all of Jerusalem except the Jewish and Armenian quarters, with Jews preserving the right to worship at the Temple Mount; and a thirty-billion-dollar compensation fund.48

However, as Ross reported, President Clinton offered the Palestinians not 97 percent per se “of the land of the occupied territories,” as Walsh reported, but 94 to 96 percent, with a swap of unspecified land from Israel of 1 to 3 percent. Also, the president did not offer the Palestinians “all of Jerusalem except the Jewish and Armenian quarters,” at least as far as sovereignty was concerned; rather, Clinton’s offer to Arafat was Palestinian sovereignty of the Arab quarter in the Old City, which is a one-square-kilometer section of East Jerusalem49—the total area of East Jerusalem overall is seventy square kilometers.50

Furthermore, Walsh’s narrative is of interest for another reason. In The Case for Israel, Dershowitz spoke of “Prince Bandar, who played a central beyond-the-scenes [sic] role in the peace negotiations.”51 Yet, in her New Yorker article, Walsh detailed no input from Bandar on the content of the negotiations; she wrote that Bandar had not been involved in the peace negotiations prior to Ross approaching him about the Clinton parameters of December 2000 and there is no evidence of Bandar’s involvement with Clinton officials beyond his receipt of that single briefing from Ross.52 The portrait painted in the New Yorker is not of Bandar being an insider to the negotiations, but of Bandar agreeing to do a last-minute favor for the American administration by picking Arafat up at the airport on January 2. Despite these limitations, Dershowitz cited the New Yorker article by Elsa Walsh as a key source53 in The Case for Israel to support his claims that Arafat had rejected Barak’s generous parameters (when the parameters in fact were Clinton’s) and to assert a crucial role for Bandar “behind-the-scenes” in the negotiations (when Bandar’s role was minor). Thus, Dershowitz wrote: “In a remarkable series of interviews conducted by Elsa Walsh for the New Yorker, Prince Bandar of Saudi Arabia has publicly disclosed his behind-the-scenes role in the peace process and what he told Arafat. Bandar’s disclosures go well beyond anything previously revealed by an inside source to the negotiations and provide the best available evidence of how Arafat plays the terrorism card to shift public opinion not only in the Arab and Muslim worlds but in the world at large.”54

Taba, January 21–27, 2001. Nearly three weeks after Arafat’s meeting with President Clinton on January 2, 2001—and after Ross rejected Arafat’s request for clarifications—bilateral negotiations between Israeli and Palestinian negotiators were conducted at Taba on January 21–27. As to the question of which side ended these negotiations, one might turn to what a couple of genuine insiders to the peace talks—Israeli journalist Akiva Eldar and Israeli negotiator Yossi Beilin, who was present at Taba—have written about this question. In his introduction to the “Moratinos Document,” which is a first hand summary of the Taba negotiations by the European Union’s representative to the Taba talks, and which was published for the first time in Ha’aretz in February 2002, Eldar reported what Beilen had told him about the Taba negotiations: “Beilen stressed that the Taba talks were not halted because they hit a crisis, but rather because of the Israeli election” on February 6, 2001.55 In his 2004 book about the peace process, Beilin himself wrote: “The talks at Taba were stopped on Saturday night, January 27 [2001], because Shlomo Ben-Ami [chief Israeli negotiator] and Abu Ala [chief Palestinian negotiator] agreed that it would be difficult to reach further breakthroughs at that juncture. It was resolved that the talks would continue in a more limited framework over the next two days, ahead of a possible summit meeting between Barak and Arafat in Sweden on the thirtieth [of January]. . . . But a series of events prevented the summit.”56

With respect to those events, Beilin wrote about Arafat’s reaction to the lethal Israeli response (detailed earlier) to the Palestinian Intifada that had begun on September 29, 2000: “And then on Sunday [January 28, 2001], Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat appeared before a large audience at Davos [Switzerland], and after Peres’s speech, Arafat issued a poisonous attack on the Israeli government. He accused Israel of using non-conventional weapons and deliberate economic suffocation, in language reminiscent of the pre-Oslo Arafat.” According to Beilin, and due to Arafat’s speech, “the irreversible impression had been created that Arafat was not prepared for a reconciliatory summit meeting.” Beilin wrote that “Barak was stunned by [Arafat’s] speech and the tone with which it was presented.” Arafat then “attempted to correct himself, and expressed his desire to reach an agreement, but this could not soften the harsh impression he had made.” Barak “said that he would not meet with Arafat in light of the Davos speech, but later decided not to close the door on the summit.” After no summit invitation had been issued by the Swedish government, and after three Israeli settlers were killed in the West Bank by Palestinians around that time, “Barak announced that there would be no summit meeting with Arafat.”57 Thus, Barak—not Arafat—cancelled the summit and terminated the peace process. Days later, Ariel Sharon defeated Barak in the Israeli election of February 6.

While Dershowitz may be the most prolific U.S. proponent of the view that Arafat rejected peace at Camp David in July 2000 and resorted instead to terrorism on September 29, 2000, he is not its only advocate. For example, in his 2009 polemic One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict, Israeli historian Benny Morris dramatically interpreted the failure of the peace negotiations in 2000 as a rejection by the Palestinians of a two-state solution to the conflict:

Had the Palestinian national movement really abandoned its one-state goal? As with 1937 and 1947, the year 2000 represented a milestone in the Palestinian approach to a solution to the conflict. But, in a sense, it was a more defining milestone than its predecessors. For in 1937 and 1947, in rejecting the two-state solutions proposed, respectively, by the Peel Commission and the UN General Assembly, the Palestinian Arabs had merely been expressing their consistently held and publicized attitude toward a resolution of the conflict; only a one-state solution, a Palestinian Arab state with a miniscule, disempowered Jewish minority, was acceptable. In rejecting the two-state solution offered, in two versions, in 2000, they were also—so it seemed—reneging on a process and on a commitment they had made, and repeated, in the course of the 1990s. And whereas in 1937 and 1947 they had rejected merely a two-state vision, a possibility, as it were, in 2000 they were also rejecting a reality, denying the legitimacy and right to life of an existing state [Israel], subverting a principle on which the international order rests.58

In the United States, Ethan Bronner, then the Middle East editor of the New York Times, in his November 2003 review of The Case for Israel, assimilated Dershowitz’s core claim by writing, “in 2000, when Israel offered Yasir Arafat more than 90 percent of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip for a Palestinian state, his rejection was accompanied by a terrorist war that shows no sign of stopping.”59

But not everyone in the United States and Israel shares these views. On the one-year anniversary of the collapse of the July 2000 Camp David summit, New York Times reporter Deborah Sontag wrote a lengthy review of the failed negotiations, which included the following assessment:

In the tumble of the all-consuming violence, much has not been revealed or examined. Rather, a potent, simplistic narrative has taken hold in Israel and to some extent in the United States. It says: Mr. Barak offered Mr. Arafat the moon at Camp David last summer. Mr. Arafat turned it down, and then “pushed the button” and chose the path of violence. . . . But many diplomats and officials believe that the dynamic was far more complex and that Mr. Arafat does not bear sole responsibility for the breakdown of the peace effort. . . . Mr. Barak did not offer Mr. Arafat the moon at Camp David. He broke Israeli taboos against any discussion of dividing Jerusalem, and he sketched out an offer that was politically courageous, especially for an Israeli leader with a faltering coalition. But it was a proposal that the Palestinians did not believe would leave them with a viable state. And although Mr. Barak said no Israeli leader could go further, he himself improved considerably on his Camp David proposal six months later [at Taba]. “It is a terrible myth that Arafat and only Arafat caused this catastrophic failure,” Terje Roed-Larsen, the United Nations special envoy [to the Palestinian territories], said in an interview. “All three parties made mistakes, and in such complex negotiations, everyone is bound to. But no one is solely to blame. . . .” Despite reports to the contrary in Israel, however, Mr. Arafat never turned down “97 percent of the West Bank” at Taba, as many Israelis hold. The negotiations were suspended by Israel because elections were imminent and “the pressure of Israeli public opinion against the talks could not be resisted,” said Shlomo Ben-Ami, who was Israel’s foreign minister at the time.60

Nearly a year after this article in the Times was published, a Benny Morris interview with Ehud Barak appeared in the New York Review of Books in June 2002, which began with Morris describing a phone call that was placed the year before to Barak by former president Clinton: “The call from Bill Clinton came hours after the publication in the New York Times of Deborah Sontag’s ‘revisionist’ article on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process.” Barak took the call while swimming in a cove in Sardinia. Clinton said (according to Barak, via Morris): “What the hell is this? Why is [Sontag] turning the mistakes we [the U.S. and Israel] made into the essence? The true story of Camp David was that for the first time in the history of the conflict the American President put on the table a proposal, based on U.N. Security Council resolutions 242 and 338, very close to the Palestinian demands, and Arafat refused even to accept it as a basis for negotiations, walked out of the room, and deliberately turned to terrorism. That’s the real story—all the rest is gossip.”61 As Morris noted, “Clinton was speaking of the two-week-long July 2000 Camp David conference that he had organized and mediated and its failure.”62

While quoting Barak referring to those who challenged the Clinton-Barak rendition of the negotiations as “revisionists,” Morris wrote: “Regarding the core of the Israeli-American proposals, the ‘revisionists’ have charged that Israel offered the Palestinians not a continuous state but a collection of ‘bantustans’ or ‘cantons.’ ‘This is one of the most embarrassing lies to have emerged from Camp David,’ says Barak.” Morris then quoted Barak as follows: “I ask myself why is [Arafat] lying. To put it simply, any proposal that offers 92 percent of the West Bank cannot, almost by definition, break up the territory into noncontiguous cantons. The West Bank and the Gaza Strip are separate, but that cannot be helped.”63 (Note that Barak apparently was referring to his final offer at Camp David of 92 percent of the West Bank to the Palestinians.)

Finally, in response to Benny Morris’s interview with Ehud Barak in June 2002, Robert Malley, who in July 2000 was director for Near Eastern Affairs in Clinton’s National Security Council and a U.S. negotiator with Dennis Ross at Camp David,64 and Hussein Agha, a Palestinian negotiator at Camp David,65 disagreed with the Barak-Morris explanation of why the 2000 peace negotiations failed. They wrote, also in the New York Review:

Barak’s assessment that the talks failed because Yasser Arafat cannot make peace with Israel and that his answer to Israel’s unprecedented offer was to resort to terrorist violence has become central to the argument that Israel is in a fight for its survival against those who deny its very right to exist. So much of what is said and done today derives from and is justified by that crude appraisal. . . . The one-sided account that was set in motion in the wake of Camp David has had devastating effects—on Israeli public opinion as well as on U.S. foreign policy. That was clear enough a year ago; it has become far clearer since. Rectifying it does not mean, to quote Barak, engaging in “Palestinian propaganda.” Rather, it means taking a close look at what actually happened.66

One of the things that happened during the discussions among U.S. negotiators between the Camp David summit in July and the presentation of the Clinton parameters in December, as reported by Dennis Ross in The Missing Peace, was a conversation between Ross and his aides, including Robert Malley and Aaron Miller. Ross wrote:

Our internal discussions were heated. Indeed, I would often say that if outside observers saw our discussions, they could easily conclude that we disliked each other. They would have been dead wrong. Our passion for the issue—the desire for peace—was an extraordinary unifier. It was a bond that we shared. However, we also felt the responsibility that came with putting an American proposal on the table. Suddenly our judgments about what would work also came into conflict with what we thought was right or just or fair. Aaron [Miller] was also arguing for a just and fair proposal. I was not against a fair proposal. But I felt the very concept of “fairness” was, by definition, subjective. Similarly, both Rob [Malley] and Gamal [Helal] believed that the Palestinians were entitled to 100 percent of the [Gaza and West Bank] territory. Swaps should thus be equal. They believed this was a Palestinian right. Aaron tended to agree with them not on the basis of right, but on the basis that every other Arab negotiating partner had gotten 100 percent. Why should the Palestinians be different? I disagreed. I was focused not on reconciling rights but on addressing needs.67

While foregoing any actual examination of Palestinian rights under international law, and declining to explain why Israel’s political “needs” might trump Palestinian territorial rights, Ross noted: “I felt that that the Israelis needed 6 to 7 percent of the [Palestinian West Bank] territory for both security and political purposes,” while also observing one paragraph later: “I felt strongly about a 6 to 7 percent [Israeli] annexation [of Palestinian territory], and I was not prepared to lower the ceiling. Nor was I prepared to introduce the idea of an equivalent [land] swap.”68 In fact, at no time throughout the 2000 peace negotiations, under the tutelage of Bill Clinton and Dennis Ross, did the United States or Israel acknowledge that the Fourth Geneva Convention renders the Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem and the West Bank illegal and that Israel had no right to retain any of its settlements (see chapter 6 in this volume), or that the Palestinians at a minimum had a right to a one-to-one territorial swap as a fair measure of compensation for any Israel-annexed Palestinian land.

While former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak referred to those who found fault with the official edition of facts as “revisionists,” Dershowitz was less restrained while referring to the same group of commentators as “enemies of Israel.” Thus, how did Israel’s “enemies”— Noam Chomsky, Richard Falk, Edward Said, and Norman Finkelstein, identified as such in Dershowitz’s 2008 book The Case against Israel’s Enemies—describe the events of 2000? Here are a few brief samples, all of which more accurately reflect the facts than what Dershowitz has written about the negotiations.

In Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy, published in 2006, Chomsky wrote:

In the real world, the Camp David proposals could not possibly be accepted by any Palestinian leader (including [Mahmoud] Abbas, who rejected them). That is evident from a look at the maps that were easily available from standard sources, though apparently are nowhere to be found in the U.S. mainstream. In the most careful analysis, Ron Pundak and Shaul Arieli conclude that Barak’s opening offer left Israel in control of 13 percent of the West Bank . . . though Barak’s final offer reduced it to 12 percent. The most authoritative map, which Pundak provided in another analysis, reveals that the U.S.-Israeli proposal established three cantons in the remnants of the West Bank left to the Palestinians. The three are formed by the Israeli salients [corridors] extending from Israel well into the West Bank. . . . The effect is largely to separate the southern and central [West Bank] cantons from the northern one. Along with other significant expansion, the proposals effectively cut off the major Palestinian towns (Bethlehem, Ramallah, Nablus) from one another. And all Palestinian fragments are largely separated from the small sector of East Jerusalem that is the center of Palestinian commercial, cultural, religious, and political life and institutions.69

In a 2003 volume Unlocking the Middle East: The Writings of Richard Falk, the Princeton professor of international law wrote:

It has been endlessly repeated, without any demonstration, that the Israelis under Prime Minister Ehud Barak made a generous offer at Camp David in the summer of 2000. It is then alleged that Arafat rejected an offer he should have accepted and resumed armed struggle. Further, it has been alleged that Arafat’s rejection was tantamount to saying that the struggle was not about establishing a Palestinian state but about ending the existence of the Jewish state. It was this one-sided assessment, alongside others, that led to [Ariel] Sharon’s election, which meant that Israel would henceforth be represented by a man with a long record of uncompromising brutality toward Palestinians and a disregard of their legitimate claims for self-determination.70

Writing about the September 28, 2000 visit by Likud leader Ariel Sharon to the Haram al-Sharif / Temple Mount and the start of the Second Palestinian Intifada, Edward Said wrote this analysis in his 2001 volume The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After:

Misreported and flawed from the start, the Oslo peace process has entered its terminal phase of violent confrontation, disproportionately massive Israeli repression, widespread Palestinian rebellion and great loss of life, mainly Palestinian. . . . Labor and Likud leaders alike make no secret of the fact that Oslo was designed to segregate the Palestinians in noncontiguous, economically unviable enclaves, surrounded by Israeli-controlled borders, with settlements and settlement roads punctuating and essentially violating the territories’ integrity. Expropriations and house demolitions proceeded inexorably through the Rabin, Peres, Netanyahu, and Barak administrations, along with the expansion and multiplication of settlements, military occupation continuing and every tiny step taken toward Palestinian sovereignty—including agreements to withdraw in miniscule, agreed-upon phases—stymied, delayed, canceled at Israel’s will.71

In his 2005 book Beyond Chutzpah, which scrutinized in detail numerous factually problematic claims by Dershowitz, including those relating to the 2000 peace negotiations and the start of the Second Palestinian Intifada,72 Finkelstein wrote: “During the early weeks of the second intifada (beginning in late September 2000), the ratio of Palestinians to Israelis killed was 20:1, with the overwhelming majority of Palestinians ‘killed in demonstrations in circumstances when the lives of the [Israeli] security services were not in danger’ (Amnesty International).”73 Furthermore, in a lengthy review of Dennis Ross’s book The Missing Peace, with a focus at one point on the matter of Ross’s subordination of established Palestinian rights to Israel’s domestic political needs, Finkelstein wrote: “It is not immediately obvious why a standard of rights reached by broad international consensus and codified in international law is more ‘subjective’ than a standard of needs on which there is neither consensus nor codification. . . . What is most peculiar about Ross’s argument is his apparent belief that his personal adjudication is less arbitrary than reference to a consensual body of laws.”74

According to the Anti-Defamation League, the Palestinian terrorist attacks that killed and injured civilians inside Israel began on October 28, 2001—not on September 29, 2000—and continued as follows:

These terrorist attacks initiated a long line of Palestinian terrorist attacks against Israel, most of which targeted and killed Israeli civilians, violated international humanitarian law and human rights law, and were deplorable and criminal acts. If the policy objectives of the United States and Israel are to prevent such terrorist acts, one should note that the long sequence of terrorist attacks on Israeli civilians in this instance began more than a year after the onset of the Second Palestinian Intifada on September 29, 2000, and thus well after Israeli security forces had killed hundreds of Palestinians, including many Palestinian children, while injuring many thousands more, including those who were severely injured and permanently disabled. Furthermore, these lethal Israeli attacks on Palestinians not only violated humanitarian law and the human rights of the Palestinians who were killed and injured, they followed peace talks at which both the United States and Israel ignored Palestinian territorial rights under international law, as Dennis Ross, the chief U.S. negotiator, clearly concedes.

On the basis, therefore, of the sequence of events detailed previously, this chapter functions as a case study to support the argument in this volume that aggressive warfare by the United States and Israel generates anti-American and anti-Israel terrorism, and that a plausible theory to reduce the threat of such terrorism would be for the United States and Israel to comply with existing international law with respect to Muslim populations. This chapter also shows that Dershowitz is an unreliable reporter of facts, and that his jurisprudence of terrorism prevention for the United States—which is grounded in misleading representations of the causes of Muslim terrorism and would probably lead to an increased threat of terrorism against the United States and increasingly intrusive counterterrorism measures—threatens the Bill of Rights.