One of the most curious friendships in the rainforest is between the wolf and the raven. Wolves have been documented eating all kinds of rainforest birds, but they’ve never been known to hunt or eat a raven.

One of the most curious friendships in the rainforest is between the wolf and the raven. Wolves have been documented eating all kinds of rainforest birds, but they’ve never been known to hunt or eat a raven.

Friends in High Places

This book began by talking about how wolves have been feared and persecuted by people almost everywhere the two live side by side—which unfortunately is almost everywhere in the wolf’s world. But not in the Great Bear Rainforest. The GBR has been home to different First Nations people for millennia—thousands of years. And far from making an enemy of the wolf, coastal First Nations have honored and respected it.

Before European explorers began colonizing British Columbia, the Great Bear Rainforest was home to tens of thousands of aboriginal people. But the way those people lived was very different from the way people live today. They relied on the forest and the ocean for everything. They ate fish, and they built their houses and crafted their canoes from the rainforest trees. They clothed themselves with skins from the animals they hunted and bark from the red cedar. Yes, they took from the forest but never more than what they needed to survive. They understood that nature was a balance, and that if that balance was tipped too far in one direction or the other, nature would suffer—and they would suffer too. It was their world, and they were part of it.

Wolves and ravens share a long and mutually beneficial history. Ravens help wolves locate prey, and wolves help bite into the carcasses of animals whose skins are too tough for raven bills to penetrate.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise to learn that just as the territories of wolves, bears and deer overlap each other in the Great Bear Rainforest today, so did the territories of animals and the villages of people hundreds of years ago. Life wasn’t a competition between them the way it is now. There were no wire fences, garbage dumps and paved roads keeping people in and animals out. The villages Native people lived in fit into the forest like a bear or wolf den. In fact, many of the wolf dens that have been identified in the Great Bear Rainforest are near what were once First Nations village sites. BC coastal First Nations didn’t drive wolves away or slaughter them as so many Europeans and North American settlers did; they lived next door to them. And they did so peaceably. First Nations people viewed the wolf as an intelligent, social and spiritually important animal. One only has to look at the carvings of wolves in their totems or the corner posts holding up their big house roofs to realize that the wolf was a culturally significant animal. Today, stories are still told that describe the wolf as a provider and protector.

But it’s not only coastal people who have had a close relationship with coastal wolves. Strange as it may sound, ravens and wolves have long been good rainforest friends, and they remain so today. Sometimes when you see a flock of ravens traveling through the forest, a family of wolves won’t be far away. And while coastal wolves will eat almost any bird they manage to catch—herons, geese, cranes, ducks, you name it—they aren’t known to eat ravens.

If you’ve never seen a raven, they look very much like the common crow, only bigger. The best way to tell the two apart is to look at their tail feathers. The raven’s form a wedge, while the crow’s are blocked off in kind of a square. Ravens are excellent fliers. They can soar hundreds of meters above the ground and travel great distances in a single day—as much as sixty-five kilometers (forty miles). They also can perform amazing acrobatics in the sky—dive-bombing and looping the loop—and have a very elaborate language. Sometimes they sound like falling water or a cat meowing. They can even imitate human language.

According to one First Nation legend, the raven created the rainforest by dropping pebbles into the sea. These turned into islands, providing a home for other rainforest animals like this spirit bear.

The raven is famous in some Pacific First Nations cultures for being the creator of the world. According to one legend, Raven created land when he grew tired of flying over an open ocean—the Pacific. He dropped pebbles into the sea that grew into the islands off what is now the BC coast. Then, using wood and clay, he made animals and humans so the islands wouldn’t be empty. This explains why the raven, like the wolf, figures so prominently in First Nations carvings and artwork.

To coastal wolves, however, the raven is important for more practical reasons. If a seal or a whale happens to wash up on the opposite side of an island, the wolves may not know about it right away. But the ravens will because they can see a lot more from the air than wolves do from the ground. So the ravens will call the wolves and tell them about the carcass. Why? Not because ravens are especially generous. In nature, creatures rarely are. Usually when they do something, they do it for themselves. In this case, deer, moose, seal and sea lion skin is tough—too tough for a raven to break open on its own. So if there’s a family of wolves willing to do it for them, why not let them? For ravens it’s like having their own crew of butchers. The only catch is that these butchers usually want their share of the meat first.

Ravens also alert wolves to intruders and help keep the places wolves live clean. They’re excellent scavengers, so they eat whatever scraps wolves leave behind. And even though this sounds gross, ravens will eat wolf droppings because there’s nutritious stuff in them. For example, when a wolf eats a seal carcass, not everything gets digested as it passes through the wolf’s gut. So a raven can benefit when it eats what’s politely known as wolf “scat.”

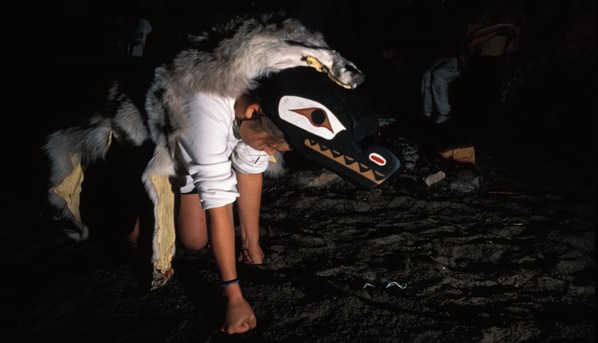

While European cultures have historically despised the wolf and most often hunted it to near extinction, First Nations cultures have always honored it. Here a group of Heiltsuk youth celebrates wolves and wolf culture at a big house.

First Nations people living along the BC coast pay their respects to wolves by wearing their skins and creating masks in their likeness.

However, the relationship between wolves and ravens is about more than just food. It’s also about fun. If you have a pet, you’ll know that animals love to play. Wild animals do too. The same Pacific First Nations who credit the raven with creating the world also credit him as a trickster. No one in the forest is said to like a game or joke better than a raven. So sometimes ravens and wolves play tag. They chase each other like children across the broad stretches of island sand. Other times ravens dive-bomb wolf pups like kamikaze pilots and then nip at their ears as they take off again. It drives the leaping pups crazy. Or if they don’t attack the pups from the air, they may act like hunting decoys on the ground. They walk in front of the pups and the pups stalk them as if they were stalking deer. But the wily raven is too clever to be caught. Just when the pup is about to pounce, the raven will fly away. This curiously endearing relationship is played out everywhere wolves and ravens exist together.

Members of the Tlingit First Nation, who live in the northernmost part of the Great Bear Rainforest, have observed this close wolf-raven relationship for centuries. In fact, the wolf and the raven have become major symbols in their culture. Every member of the Tlingit Nation belongs to either the wolf or the raven clan. Clan membership is determined by one’s mother. If your mother is a raven, you’ll be a raven too. If she is a wolf, you’ll be a wolf. According to Tlingit custom, those from the wolf clan are only allowed to marry someone from the raven clan, and ravens are only allowed to marry wolves. As well, a member of one clan must perform funeral rites for a member of the other clan. And at feast time, only wolves may serve ravens (and vice versa).

A wolf and three ravens share a misty gray day on the coast.

So, who’s afraid of the big bad wolf? Certainly not people who understand them. For millennia, it must have seemed to the Tlingit and other coastal First Nations that the rainforest belonged to them and the animals. They lived side by side as the seasons changed and the years passed. Then something happened. Two hundred and fifty years ago, European explorers set eyes on the beautiful BC coast, and nothing has been the same since. As European and, later, Asian cultures and customs overtook those of First Nations people as the preeminent cultures of British Columbia, the rainforest changed too. Industry arrived. Trees were cut. Animals were shot for sport, and rivers were polluted and emptied of fish. Explorers brought modern ways to the rainforest, and while those modern ways have brought an economic advantage to many, it has come at a terrible cost to the natural world.

The relationship between ravens and wolves isn’t always about work. Sometimes it’s about play. The raven is known by coastal First Nations as the trickster of the rainforest. No wonder. Wolves and ravens will play tag with each other, and ravens will tease wolf pups by dive-bombing them like kamikaze pilots and nipping at their ears as they take off again. This drives the leaping, yelping pups crazy, but the ravens don’t care. They’re enjoying themselves too much.