Those of us who cut wood for a living know that it is hard work and that by afternoon you may be pretty much on automatic pilot. I complained to a farmer friend that I was getting so old that when I pulled my foot out of a tree crotch where I’d wedged it, I got plantar fasciitis that took two months to heal. “Tell me about it!” he roared. He rolled up both pants legs and one shirtsleeve to show he was wearing braces on one elbow and both knees.

It will not do to romanticize the art of cutting wood. Still, it was and remains a remarkable and responsive kind of work. The more the hand learns, the more the brain knows, and the more the brain imagines, the more the hand tries something new. It is practical physics, joined to practical biology. One of the most common uses for coppiced hazel was to help shape hedges. The best of these living fences could stop a charging bull while simultaneously keeping a lamb or even a rabbit from shimmying through beneath. It had to be very strong and very thick.

There is evidence that the art dates at least as far back as 6000 BC. The word hedge itself has survived almost unchanged from the Proto- Indo-European, always meaning fence. Hedge laying was already fully developed by 57 BC, when Julius Caesar noted a hedge that he encountered in what is now Belgium:

The Nervii, in order that they might more easily obstruct their neighbours’ cavalry who came down on them for plunder, they half cut young trees, bend them over and interweave the branches among them, and with the brambles and young thorns growing up, these hedges present a barrier like a wall, which it is not only impossible to penetrate but also to see through.

The military-minded Caesar may have mistaken for a fortification what was in fact a means to keep cattle in, not marauders out. Still, his report is testimony to the strength of the barrier. Wire fences began to replace hedges late in the nineteenth century. During the Great Depression, neglect of hedges led to their losing their form, a good excuse to change to the apparently cheaper wire. And at some point, the cash-cropping agro-businessperson began to realize that the damned hedge covered two acres for every hundred. Why should he not turn that additional land to make a profit? Between 1947 and 1985, more than 96,000 miles of hedge were grubbed up and thrown out. Hedge laying would have become a lost art by the 1970s, had it not been for those parishes and counties in England and elsewhere, where hunters wanted hedges for their steeds to leap in pursuit of the fox. Leicestershire, for example, where foxhunting is a leading pastime, is famous for having the best hedges and the best hedge layers. There, the tradition never died. When Ernest Pollard and his colleague wrote their wonderful book Hedges in 1974, there remained 620,000 miles of hedge in Britain alone. Later in the twentieth century, this man-made ecosystem acquired prestige for its diversity. Then, too, somebody bothered to calculate the life cost of a wire fence versus a living quickset hedge. It was found that over the fifty-year life of a hedge, before it needed to be relaid, the costs of keeping the living fence was less than that of buying, placing, and replacing barbed wire. (One nineteenth-century wire maker is said to have had his tombstone crafted out of wire, but now it has rusted away.) As hedge laying begins again across Europe, it is to these counties that people go to learn.

Hedging is a beautiful and a technical art. To lay a hedge, in accord with the ancient meaning in Old English, Old Dutch, and Old German, is to cause the plants to lie down, creating a fence. The billhook is the principal tool. There are still more than a dozen kinds of billhook, but each is a short-handled tool with a blade about a foot long and usually with an end that seems to bend back upon itself. It looks dull and bulbous—phallic, in fact—but it is actually razor sharp, at least from the handle along the blade and out to the fat distal bend. Some billhooks are bladed on both bottom and top, so the handle is the only thing that won’t cut you.

Hawthorn is the most common hedge plant, blackthorn (also known as sloe) second, but almost any broadleaf plant can be used. You establish a row of five- or six-foot-tall plants along the future hedge line. Both the art and the science are in the stroke with the hook. Each little tree is called a pleacher. You support the pleacher near its top, while you bend over with the tool in your opposite hand. (This is why right handers usually lay left to right and left handers right to left.) The cut should enter the trunk at a height about three times the diameter of the stem, but who has time to measure, since you have hundreds of thorns to lay. It is a matter that, with time and work, the hand, eye, and brain make good. The cut must angle in steeply through the tissue, then flatten out along the stem, creating a thin strip of unsevered living wood called the tongue, stretching as near to the base of the stem as possible, without severing it at any point. The tongue needs to be thick enough that it will not break when you lay the thorn down to the 30–50 degree angle at which it will rest in the hedge. It needs to be thin enough that when you lay it down the bark does not split away from the stem, killing the slim tongue. The upstanding stump that your cut leaves in the ground is called the heel. The next cut reduces the heel, cutting it low at an angle that mimics the direction of the cut into the tongue.

Strength, decision, and delicacy meet in the stroke. Then, too, you need a little nick and tuck in the tops—light cuts to make stems easily bent or to remove unwieldy ones—to get one laid thorn to rest comfortably against its neighbor, and you must angle each a little toward the field side of the hedge, so that good light comes to the heel.

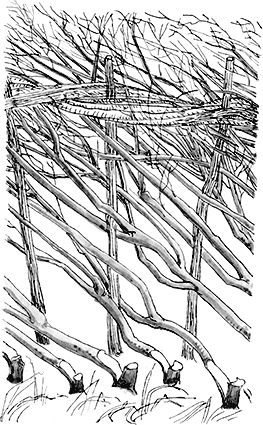

Pleachers with their tongues, stakes, and binders in a new-laid hedge.

Next comes the hazel. You need two sorts of coppiced rods, the first pile about 5 feet long and an inch and a half to two and a half in diameter at the thick end, the second about 8 feet long and no more than an inch thick. The first makes the stakes. A good hedge layer rests the thick end against his thigh and cuts a four-angled point with the billhook, revolving the stake as he cuts. (The trick is not to shave your leg, or worse, while doing it.) He knocks off the head of the stake to make a flat top. Many hedge layers even today use the old ell measure—from the elbow to the tip of the fingers—to space the stakes in the hedge, driving each in solid a little to the field side of the row. Again, the idea is to keep light coming to the pleachers and the heel. The long slender rods become the binders that join pleachers to stakes and hold the new hedge in place. Two by two, the maker twists the hazels, running them in front of and then behind and then in front of a set of stakes. He weaves one strand of the next pair back into the preceding braid and so on, making a thick twining rope of the 8-foot rods. The stakes and the binders make the hedge sturdy from the start.

Why so complicated? Most of us have clipped a modern hedge at least once. You can see that nowadays they just put the shrubs—privet or box or yew—close together, and then shear them into a single unit as they continue to grow. Nothing to it, especially with a gas or electric trimmer, though when you use hand trimmers, particularly the Japanese carbon steel ones, you can very much enjoy the act of shaping. But what cast of the primitive mind made these peoples of the past so fussy? Why did they pleach, why twine and plait the stems, and why make a fence out of hazel interwoven with a hedge of thorns?

It is hard for us who get most of our meat at the supermarket to imagine a time when the loss of lambs or the wandering away of a herd of cattle might have serious consequences for our lives and the lives of our families. We might be losing soup, meat, leather, wool, shoes, pants, sweaters, tunics, fertilizer, our stock in trade, and the potential increase of our herd. The escaped creatures might also end up grazing in someone else’s fields, resulting in fines and restitution.

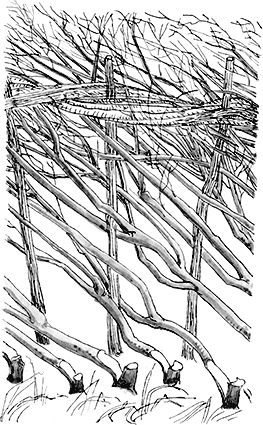

An often-sheared hedge, likely at least eight hundred years old, in winter.

The point of a laid hedge is to be impermeable from day one. The strength and durability of the hedge will come from its sprouting. Some of the stems will rise from laid trunks of the thorns, but most will jump up from the heels. Over time, the hedge will become thick with living growth, so that an annual trimming—like the one we give a present-day hedge—will suffice to keep it thick and happy. It may be fifty years before it will need to be relaid. But it is the slant-laid living trunks and the frame of hazel stakes and binders that directs the ingrowth and that gives bull-proof stability to the hedge from the moment it is laid.

From the Neolithic until the 1900s, most of Atlantic Europe used laid hedges to keep its stock in bounds. From a distance or even from the air, you can tell an old hedge, because it is bendy, irregular, following the line of a stream or a slope, a dell or a trackway. In England, some of the boundary hedges that are drawn in the eleventh-century Domesday Book are still in place and still trace the same line on the ground. Such a hedge has been relaid many times and clipped countless thousands. Some are derelict, having grown up into rough open lines of trees and shrubs.

As Pollard and his colleagues showed, the older a hedge is, the more species of trees and shrubs inhabit it, adding very roughly one additional species per century, as birds dropped, squirrels buried, and the wind blew. An ancient hedge has likely at least acquired hazel, dogwood, field maple, serviceberry, spindle bush, and sloe. They might also take into their folds or even be interplanted with bramble, currant, cranberry, bilberry, moorberry, strawberry, pear, apple, medlar, viburnum, beech, oak, walnut, rose, crab apple, sallow, juniper, and pine. In the understory are dog’s mercury and wood anemone. Not far southeast of London is a hedge that was catalogued in a Saxon charter. There is no dominant species in it, but it contains hazel, hawthorn, oak, two native roses, field maple, dogwood, crab apple, and two willows, ten species in all. Another old hedge near Salisbury has twelve species. By Pollard’s count, then, those hedges are about one thousand years old and twelve hundred years old, respectively

Quickset is a lovely name. It refers to the hawthorns that are often the key plant in the hedge: thorny and thick. When I was a kid in church, they intoned each week, “He will come again in glory to judge the quick and the dead.” I had a vision of God’s hand grabbing us no matter how fast we ran away. Quick means alive. So the quickset in the hedge is not only the fast-growing, long-lasting plant, but also the hawthorn that is set there not as seeds or cuttings but transplanted as living plants. Many of the great nurseries now quick in Europe began by supplying quickset to the hedge-laying trade.

About half the hedges surviving in England predate the eighteenth century. The sixteenth-century agricultural poet Thomas Tusser—a worthy vernacular successor to Cato and Virgil—peppered his Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry with hedge advice. Then, the quickset was either gathered or bought at market.

Leave grubbing or pulling of bushes, my son

Til timely thy fences require to be done.

Then take of the best for to furnish thy turn

And home with the rest for the fier to burn.

Hedge making often involved interplanting with other useful trees:

Buy quickset at market, new gathered and small,

Buy bushes or willow, to fence it withall:

Set willow to grow, in the stead of a stake,

For cattle in summer a shadow to make.

The stakes and the binders (called edders) were also often gathered in the course of other cutting:

In lopping and felling, save edder and stake,

Thine hedges as needed to mend or to make.

The practice was so widespread and so common that people took their names from it. All the Hayes, Hays, Hedgemans and Hawes, the Haigs and the Hages; the Hagelens, Hagemans, Haggarts, and Hagers; the Hagedorns, Hagles, Hagstroms, and Haglunds; the Haines, the Hainers, and the Hakes, the Haywoods and Hayworths, either lived beside hedges or made them. (Hay once meant hedge, as in the High Hay for a tall hedge.)

Then came the Enclosures, a movement that seized most of the common land in Britain, privatizing it and hedging it round. It was a jackpot for hedge layers and the makers of quickset, though a disaster for the millennial culture of the commons and the independence of those who lived by them. (Here first, not with the factory, is where the craftsman was turned into a laborer.) During the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714), only about 1,500 acres were enclosed. Her successor, George I (1714–1727), presided over the seizure of almost 18,000 acres, but that was just the beginning. Under George II (1727–1760), almost 320,000 acres were enclosed, and under George III (the one who lost the American colonies), the total was almost 3 million acres.

Each privatized field needed a new hedge. This was the beginning of the reign of number and proportion, so you can tell an enclosure hedge from an old hedge not only by the smaller number of species but by the fact that the newer hedge is straight, measured corner to corner in furlongs (furrow lengths) or chains. Quickset, usually nursery bought, was the prime ingredient, with perhaps a little sloe mixed in. Where an old hedge bordered a road or wood, however, it was sometimes incorporated into the enclosure hedge. An enclosure-age hedge is more likely to add the spreading sloe, roses, ash, and elderberry. All may be cloaked with opportunist vines: bryony, clematis, bindweed, honeysuckle. Some vines are so common in the hedges that they take their common names from them: hedge feathers, hedge bells, hedge lily, hedge cherry.

The living hedge is a linear forest, on average about 6 to 9 feet high—with the occasional 30- to 50-foot pollard in the older hedges—and about 6 to 8 feet wide. The miles of this forest in 1974 in Britain alone would circle the Earth at the equator six and a half times. It is a remarkable product of human skill, imagination, and learning, in concert with Great Nature. Because the forest is all edge, it has a remarkable diversity of invertebrates, who attract an equally extraordinary number and variety of birds. In a healthy hedge, you will find 209 different species of insects and mites on the hawthorn alone, 153 on the sloe, 118 on crab apple, 107 on wild rose, 106 on hazel, 98 on beech, 51 on field maple, 48 on honeysuckle, and 19 on spindle. On the fruit of these sun-loving plants feed blackbird, song and mistle thrush, the fieldfare and redwing. (Cuckoo is the symbol of spring, as we have seen, as fieldfare and redwing are of the end of autumn.) Some both feed and breed; among the commonest are the blackbird, chaffinch, hedge sparrow, linnet, cuckoo, greenfinch, robin and wren, whitethroat, and yellowhammer. Pollard figured that if there is roughly one breeding pair of any species per hundred yards of hedge, then there must be about 10 million hedge-breeding birds in England.

In the United States, Louis Bromfield wrote about a small farmer in his neighborhood in rural Ohio, who unlike his neighbors in the 1930s had not ripped out the hedges to plant more corn. His hedges were far more basic than English ones, but they also increased diversity. Bromfield described finding the old man kneeling and peeping into the low shrubs of the hedge. When the farmer noticed Bromfield, he invited his neighbor to quietly see the young bobwhites almost invisible in their tiny nest on the ground. “They used to laugh at me for letting the bushes grow up in my fence rows, but they don’t anymore,” said old Walter. “When the chinch bug comes along all ready to eat up my corn, these little fellows will take care of ’em.”

It was not only creatures that took sustenance from the hedge. So did people. The pollards in ancient hedges went for firewood, charcoal, and fencing, some even for shipbuilding. There are still tens of thousands of pollards in the old hedges of eastern England. Fruits and poles were also important. Edge hazel was coppiced for stakes and binder to make more hedges. Willow could be coppiced for basketry, fences, and clothespins. Crab apple and rose hips and blackberries made jams and jellies. Blackthorn gave its flavor to sloe gin. Elderberry was as good for jam as for wine.

Whether or not a living hedge is cheaper or lasts longer than a wire fence, whether the creatures living in the hedge are on balance better or worse for the crops in the field, whether diversity is better in itself or not. . . . Perhaps these nicely weighed matters of debate miss the point. The making, the maintenance, and the use of a living hedge require attention and response. A good hedge layer like Clive Leake has an intelligence focused not strictly on innovation but on seeing what is before his eyes clearly and responding in a way that helps it to go on. The phrase to “size up” in fact comes from hedge laying, for when it is time to re-lay an aging hedge, the skill of the maker is in choosing which stems to eliminate, which to choose as his new pleachers, and how low to cut them.

We would be better to focus more on acts and less on looks. Hedging puts us into the landscape intimately. It makes us pay attention. When we pay attention, we are repaid in many ways. Attention manifests itself in our activity, not simply in our reflection. The activity may produce only marginal benefits, but the attention multiplies these exponentially. My father always patted his plants; the biodynamic gardeners make elaborate and strange preparations using herbs, minerals, and cow horns, elixirs stirred a prescribed number of times in one direction and then in another. Who knows what outward effect these actions have, but attention is first, prior to what we do, which is always an experiment. The experiment without attention is usually counterproductive, regardless of its content.

We learn best in response to the living. The English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead thought that the condition of our intelligence in fact depended on the responses mediated by our hands: “There is a coordination of senses and thought, and also a reciprocal influence between brain activity and material creative activity,” he wrote. “In this reaction, the hands are peculiarly important. It is a moot point whether the human hand created the human brain, or the brain created the hand. Certainly, the connection is intimate and reciprocal.”

We live not in a world of things, but of neighbors. Each neighbor responds to the others. The real question is not “How can I become more efficient and show better numbers?” but rather “In what I am doing, am I a good neighbor or a bad?”

I said something like this to a friend, who replied, “Come on! We can’t go back to the nineteenth century!”

“Yes, I agree,” I said. “How about the twelfth?” If we are to get out of the dead end that our mastery of nature has backed us into, we will need to draw a much larger circle in time.