At the Metropolitan Museum we are working to keep our trees young. We prune them to preserve them in their youngest stage of life. In Leitza and at Burnham Beeches and at Epping Forest in London, Helen Read and her colleagues are caring for ancient pollard beeches, some more than five hundred years of age, seeking to make old trees young enough to last, though she works with them in the third stage of their life, when they are growing down.

Read takes seriously Aragón Ruano’s notion that these ancient, much used trees are monuments as important as cathedrals and castles, perhaps more so. In my native California when I was a boy, we learned that our hero John Muir regarded the groves of giant sequoia and redwoods in the high sierra and the coast ranges as cathedrals. They looked primordial and untouched, but in fact were the result of thousands of years of Indian craft and care (see page 207). The amazing groves of ancient beech trees in Europe—principally in England right in and near London, as well as in northern Spain and southern France—do not look in the slightest untouched. Their smooth gray trunks divide into huge rising fingers of wood that shoot straight up fifty or sixty feet into the air. They are forests of upraised hands, showing very clearly that they were cut and used by humans for hundreds of years, then let go to grow these astonishing ash-gray moon shots, but they are cathedrals just as surely as the sequoias are. Not only that, but these ancient trees even in their decay are the habitations of hundreds of beetles, pseudoscorpions, flies, lichens, mosses, and other creatures that once inhabited the wild wood, and now live nowhere else but in these ancient trees. Muir succeeded in making the big trees a stop on every tourist’s itinerary. Why shouldn’t these pollards be too?

The beeches are as seriously threatened as the big trees. When they were forgotten and let go, they began to grow in a way that cannot help but destroy them. Huge stems attached at the base to old cuts must in the long run fall apart in wind and storms, and sometimes even without these. Often, they cracked apart at the bole, or bolling. That is the place—usually six to ten feet above the ground—that they had last been cut during the early 1800s. Read must bring the trees back into relationship to people, if they are to survive, and even more than we do in front of the Met, she has no pruner to guide her, because she is doing something that has never been done. We can look to the past; she must look to the future.

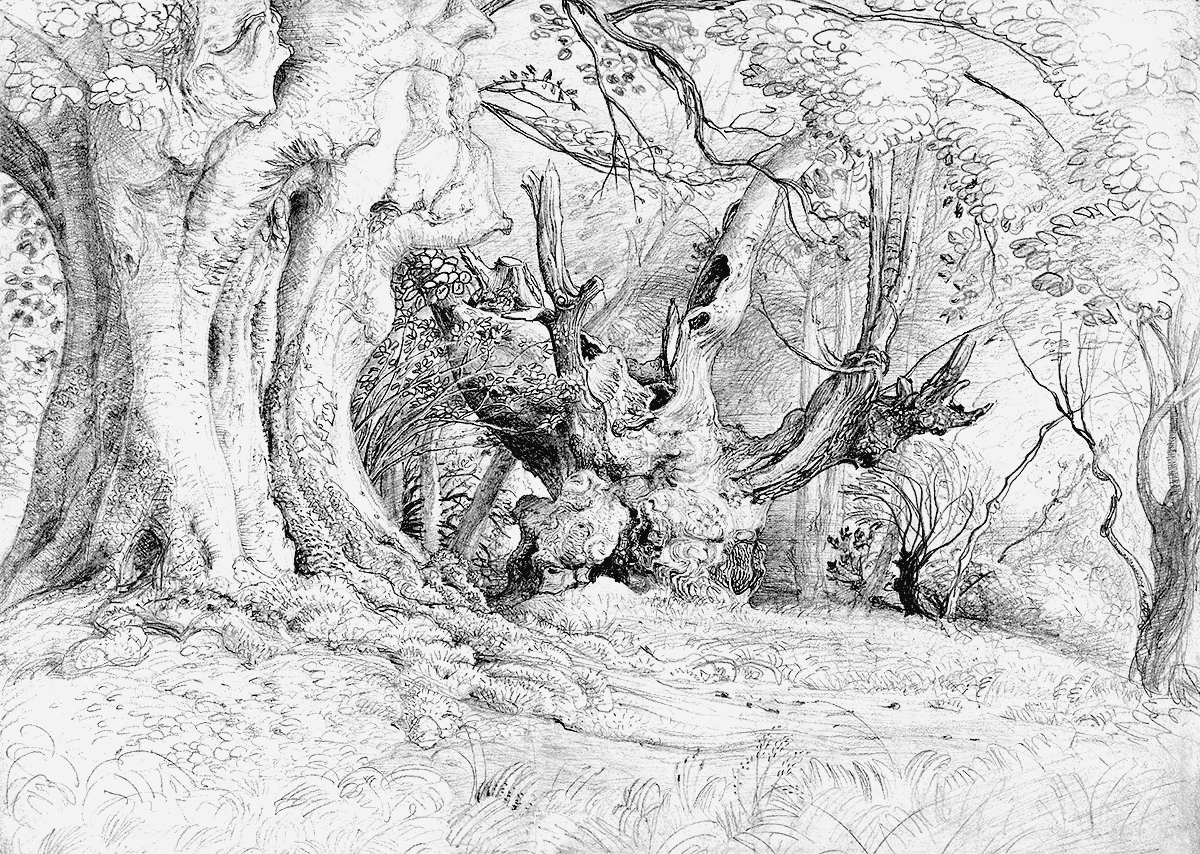

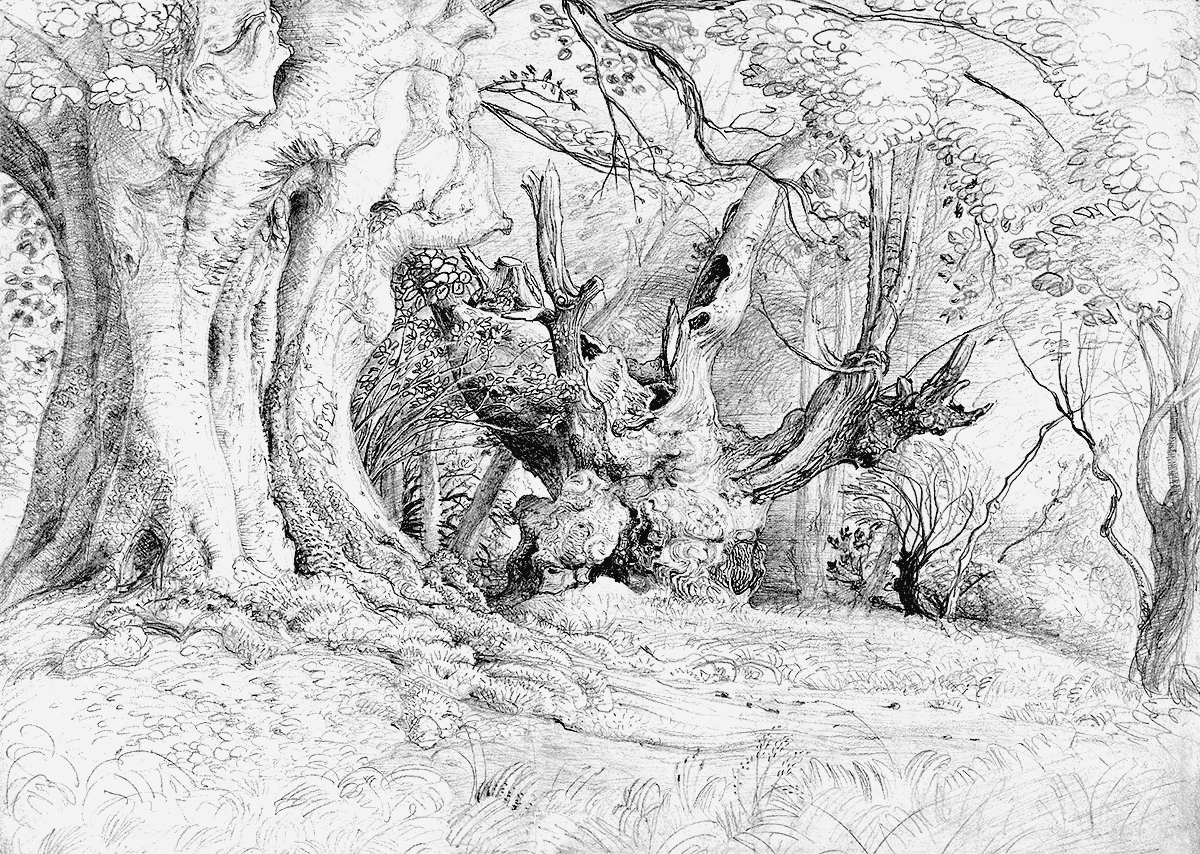

Ancient beech pollards in a drawing by William Blake’s disciple Samuel Palmer.

More than half a million people visit Burnham Beeches, on the outskirts of London, each year, and almost as many go to Epping Forest. To preserve the trees is not only to help keep the visitors unharmed, but to make sure that they see before their eyes an alternative to the world they inhabit. There was a time when people did not devour things, crumple them up, and throw them away. It is a way to remember a possible future, when we will again live in the way the people lived among the beeches.

Burnham Beeches was and is a commons. It is open to everyone. It has been so for at least the last eight hundred years. In the past, the locals had rights to grazing and to pollard firewood. They might also have made charcoal to burn bricks. Once there were 3000 pollards of beech and oak here. The last firewood cut may have been as much as two hundred years ago; the last regular grazing stopped around 1920 (though they are now beginning it again). When Read arrived here in the 1990s, there were about 957 pollard left, but they were falling apart at an alarming rate. What was to be done?

The first thought was to cut the trees right back to the bolling, a cut one or two centuries old, and so let them start over again. But how to make the cuts? Alex Shigo, the American pruning visionary, had taught that a proper pruning cut was right to the parent limb, leaving no stub. The pruners decided to try that. And, although it is shade tolerant, beech does not grow well and does not regenerate branches when it is in deep shade. Many volunteer trees had grown up around the old pollards and were shading them out, so logic dictated that the new trees should be removed, opening up the beeches once more to the light.

The results were disastrous. Trees cut back to the bolling sprouted well the following year, but thereafter they rapidly declined and died. The “proper” pruning cuts removed the many dormant buds that typically lived in the stub just beyond the parent limb. And when the surrounding trees were removed, opening the beeches suddenly to the light, their bark scalded and the trees declined.

The pruners had to try to think like the trees. If a tree had been living on its erstwhile sprouts for two hundred years, it was a poor idea to remove its livelihood all at once. Instead, they began to remove only a selection of the older stems—maybe a fifth of them—and to take them back ten or fifteen feet, but not all the way to the bolling. To keep a good supply of dormant buds, they learned, it was almost always best to leave a long stub on each cut stem, at least a foot and a half. They made sure all the while to leave active smaller branches with plenty of leaves, young sprouts to draw up the sap from the roots. After an interval of ten to fifteen years, if the trees responded well, they cut them deeper.

In releasing the beeches from the shade, they also went more modestly. Calling it “halo cutting,” they gradually pulled back the volunteer trees from around the ancient ones, sometimes only topping a volunteer, not entirely removing it, in order to bring light in gradually, a little at a time.

At Epping Forest, Jeremy Dagley was working the same way. Together, they have dramatically reduced the rate of tree failures. At the same time, they have started large numbers of new beech pollards. Read aims for a thousand new beeches, because no matter how well they care for the ancient trees, eventually those older beeches will go. The arborists play the role of the commoners, cutting new trees to begin the cycle again. For the new trees as for the old, modesty and response are the watchwords. They will cut out the tops and one or two aggressive branches, wait for the tree to reply, and then cut again.

For Read and Dagley, the trees become their teachers. They have to be patient, responsive. In 1996, C. S. Holling and Gary K. Meffe wrote an essay in the journal Conservation Biology called “Command and Control and the Pathology of Natural Resource Management.” In it, they showed how, in many different realms—in fire suppression in forests, in monoculture farming, in flood control dams, in the floodplain of the Mississippi River—the effort of human beings to impose their will upon a complex natural population led to disastrous unintended consequences. Likewise, the insistence upon making the trees look exactly “right,” quickly, led to dead trees.

In 2003, Read was on a tour of Europe to look at its ancient pollards. She sought models to help her care for the trees at Burnham Beeches. When she got to the Basque country, she was overwhelmed. Beeches, oaks, chestnuts, ash, willows, alders, poplars, and more, all had been pollarded in profusion. Thousands and thousands of them still survived. Leitza was her paradise. Beech pollard was the staple crop, seconded by oak and chestnut. More than half the forestland was beech, maybe 5 percent was oak and chestnut. She met José Miguel Elosegui and his wife and the other people in town who cared about the woodlands.

The last of the Leitza iron foundries had closed sixty or seventy years prior. Since that time, most of the beeches had never been cut. Their rising stems had grown as thick as Doric columns. Many had failed in storms. In no uncertain terms, Read told anyone who would listen how important they were and how endangered. She spoke of their cultural and historical importance, of their crucial role as an ecological niche, of their beauty and fragility. “Before Helen came,” remembered José Miguel Elosegui, “we didn’t value the pollards. She opened our eyes.” With José Miguel’s son, the forester Miguel Mari Elosegui, and a few people sent from the town council, they decided in 2005 to start pollarding again.

How should they cut the trees? At first, they followed the counsel of Miguel Barriola, who had distant memories of making charcoal in his youth. He had recalled that when as young men they had pruned the stems, they took them right back to the place that they had been cut before—that is, to the bolling. From a nest of Doric columns, they created what looked like the upthrust fist of a giant. They did the work in the waxing moon for beeches, in the waning moon for oaks. This was the timing that according to traditional wisdom got the best result.

A man named Gabriel Saralegi was there from the beginning, pruning the limbs with his sharp Urnieta axes. “We cut them way back at the beginning,” he said, “just as we cut back hard the ash and the chestnut that we still pollarded.” The response was good at first. When Read returned with a group of English arborists the following year to help with the work, she was troubled by the deep cuts. It was just what they had first tried on her London beeches. The Leitzans worked together with the English arbs but were puzzled by how little the English cut—sometimes taking off only fifteen feet from the top and sides, rather than thirty feet or more. They dubbed the cutting “estilo inglés,” English style. A group of young Spanish arborists from an association called Trepalari joined the party. Soon the three units were working together on a regular basis, exchanging traditions, experience, and hope.

At the end of 2017, they met again in Leitza for a conference that was properly dubbed, by Read’s colleague Vikki Bengtsson, “a meeting of pollard geeks.” There were talks, and there was fieldwork. Over the last twelve years, they had learned a great deal about how to restore the old beeches. Though the Basques still liked deeper cutting, they all agreed that it was important to leave some smaller leafy branches on the pruned tree. It was also good to leave “eyes,” the closed wounds where small branches had previously been pruned, since these often had many dormant buds around their edges. For the same reason, they had learned to cut leaving stubs of branches or even natural tearaways. It was crucial to make sure that all the newly cut branches had access to sun, but not to suddenly expose them. In Leitza, said Miguel Mari, they now worked annually, adding a few more trees to the restored group each season. Of those that had been cut, seventy were doing very well, thirty were fair, and eight had died. The eight were distinguished by too deep cutting and too much shade. Likewise, as they began to form new pollarded beeches—a new generation eventually to replace the old—they needed to keep the new trees in the sun. Otherwise, the trees responded poorly.

In the field, two Trepalaris did the second cut on a beech that had first been pruned in 2007. One of them learned that when you cut with an axe, you have to be able to plant your feet and swing your hips, not so easy in the top of a tree. Samuél Álvarez, with his modern saw, danced around at his rope’s end, pulling back branches by fifteen feet or more and leaving long tearaway wounds, which made it look as through the branches were sticking out their tongues. This was the polar opposite of Shigo pruning. It was a thing learned from thousands of years of culture, not only from nineteenth-century science. “No es mutilar”—It isn’t mutilation—read the T-shirt one of the Trepalaris wore.

The effect of the pruning could be seen in the cross section of one branch that the arborists had just pruned. Its inner growth rings were so tightly packed they had to be cleaned and polished to even be counted; the outer ten rings—formed since the last cut—were bold and wide, each with as great a radius as all the inner rings combined. The latter represented the first fourteen years of the branch’s life, when it had languished in the shade of other branches. The growth increment of the annual rings had been tiny. After the first cut seven years ago, the branch was released from the shade. It had grown like gangbusters, putting on large growth increments and very wide annual rings.

There had been twelve years of great practical study, like the learning of a shared language. The arborists had spoken in saw, and the beeches had answered in sprout. But why do it? Why spend all this time, energy, and intelligence on an old and superseded practice on trees that were already more than half dead?

Someone said that every civilization reaches a still point. The progressives can’t go forward, and the conservatives can’t go back. One demands continual advance, the other longs for yesterday. Both seem more than a little crazy. They growl and lunge at each other, like two packs of dogs in a small back alley. In that situation, the saying goes, you must use that stagnant point as the center and draw as large a circle as you can around it. That circle reaches much farther back in time, well beyond the short memory of the conservatives, and much farther forward, well beyond the sanguine hope of the progressives.

That, they say, is what opens the imagination and allows a way forward. It may be that a nuclear disaster, a pollution implosion—a third of the untimely deaths in the world are now from pollution—or both will occur, and then we will need desperately to know how to pollard again. God willing, no such thing will happen. Even if we never need to cut trees again as once we did, the larger circle draws on the well of deep memory. Burnham Beeches, Epping Forest and Leitza rise to the surface. We may not do exactly what they did for the reasons that they did, but they give us the power to imagine new ways to act like that. It is no longer a commons for wood or grazing, but a commons for the imagination.