E. B. White was not the first to admire a strange and apparently everlasting tree. In England, at the National Arboretum in Westonbirt, among all the mature and lovely woodland specimens, is an ancient monument. When I saw it, it consisted of several dozen low tree stumps. They were set out along the edges of a rough ring of ground about as big around as the light a street lamp casts. Within the ring, the center was empty of all but sparse grass. To one side, bound with a cord, was an amazing sheaf of several hundred poles, each about twenty feet high and four to eight inches in diameter. It looked like a gigantic sheaf of harvested wheat. All were slender trunks that during the previous winter had been cut from the ring, leaving the stumps.

The witches had told Macbeth that he would be defeated only when Birnam Wood should come to Dunsinane. The murderer-king in his castle had laughed, but the soldiers had cut trees and advanced behind them. These tall stems indeed would have done the trick. Each soldier could have carried one, the whole approaching like a wave of lime trees—limes are what the British call lindens—small for the species but big enough and many enough to hide a lot of men.

This unlikely monument was older than Big Ben. It was older than Westminster Abbey, older than London Bridge, older than the Roman baths at Bath. It was a tree that had been cut and allowed to sprout again for about two thousand years. When it had been a seedling, Jesus had been teaching in Galilee. Then, it might have grown into a tree with a trunk about a foot in diameter. Likely, there had been many more limes around it. The people who lived there had cut each tree to the base, confident that it would sprout new stems.

Every decade or so, they repeated the process, harvesting the tall slender trunks that had grown back. The cut poles might simply be used for firewood, or converted into charcoal to fuel pottery, iron, or glass works. They might be used for wattle and daub, the infill that made the walls for houses. They could be used for posts or turned for chair legs. The inner bark—the tough and stringy phloem layer—might be peeled and woven into a durable, serviceable rope. New trunks on the periphery of the old ones grew back again, and so decade by decade, the original trunk expanded to a fairy ring of dozens and eventually of hundreds of rising stems. The cycle had gone on for centuries, as dark ages came and went, royal wars were fought, the parliament rose, and the modern age came on. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the wood was still harvested for use.

It is as important a monument as many that are much taller and that look much finer. It is not a dead thing: a house or a castle or a church. It is a living cathedral dedicated to the power of sprouting. As often as you cut it, all by itself it grows its pillars again. It remembers the long age when such self-renewing wood was the foundation of cultures around the world—from Japan to Norway to Bulgaria to Afghanistan to Morocco to Sierra Leone to California—and when it led to the birth and the long long life of the healthiest woodlands that human beings have ever known. It is a monument to the world founded on coppice and pollard.

I say the words with love and reverence: coppice and pollard. My listeners, whether they be students, clients, friends, or strangers, say, “What are you talking about?” From ten millennia to about two hundred years ago, every person in every forested part of the world would have known exactly what I meant. Indeed, they themselves would have been alive and thriving because of coppice and pollard. We should know these words again, for by means of them, people built their world out of wood for ten thousand years. The persistence, power, intelligence, patience, and generosity of the trees guided them. Home, culture, poetry, and the spirit were shaped by the cutting of trees. Long before the word “sustainable” had ever been coined, human beings learned a way of living with their woodlands that benefited and sustained them both.

The idea is a simple one: when you break, burn, or cut low the trunks of almost any leafy tree or shrub, it will sprout again. New branches will emerge from behind the bases, either from buds that were dormant, waiting for their cue to grow, or from twiglets newly formed by the all-powerful cambium.

A tree can’t move. It has to live where it first came up. For 400 million years, in order to stay alive, trees and shrubs learned to respond actively to damage. A wind took down a branch. An aurochs chewed a young tree right to the ground. A vascular disease killed everything above the root system. A bigger tree fell on a smaller one. A flood tipped a whole tree over. A decay fungus like the artist’s conk, Ganoderma applanatum, caused most of the plant to die back to the base. Each and all of these disasters did not necessarily end the tree’s life, because it had learned how to sprout again. Eighty percent of the trees in a leafy forest are not virgins from seed, but experienced sprouts.

At least a hundred centuries ago, people had observed what living wood could do. They needed to make fires, to weave fences, to build houses, to make bridges. Found wood was good, but what if they could multiply it? When a section of a woodland burned, they saw, many of the plants sprouted again right from the ground. The new branchlets, arching up from an existing root system, grew fast and straight. The woodsmen learned how to burn or to cut a part of a woodland intentionally and to harvest the trunks and branches that grew back. Once cut, the shrubs and the trees responded by sprouting again. If people were not greedy and timed the cuts to allow the woods time to recover, they could repeat the operation again and again.

The old Indo-European word for tree, varna, also means “to cut.” This language was spoken in the seventh millennium BC, and already embodied the idea that trees are to cut. In Europe, the cutting came to be called coppice—from Old French meaning to chop, that is, to cut with a blow. The very sharp and precise Neolithic stone axes could cleanly part a stem from its root. The earlier, Mesolithic axe had been easy to make, simply by chipping a flint, but it was more a bludgeon than a cutting tool, and it did not last long. The Neolithic axe was laboriously worked from a large flint to a size like our present axe head, sharpened carefully by pressure flaking and polished for a day or two on sandstone so that it would hold its edge.

The Neolithic went wild with varna, with coppice and sprouts. The piers on which stood the lakeside dwellings of the Swiss and German Alps, the fen bridge supports at the Somerset Levels Sweet Track, the fences and gates of every pasture, the stems for the baskets, all were made with wood that had been coppiced. How do we know that? Because each used hundreds of poles, all of about the same dimension. All must have been cut and regrown for a similar period of time, then selected and cut again. Had they not been coppiced, the people would never have been able to find so many stakes of like length and breadth.

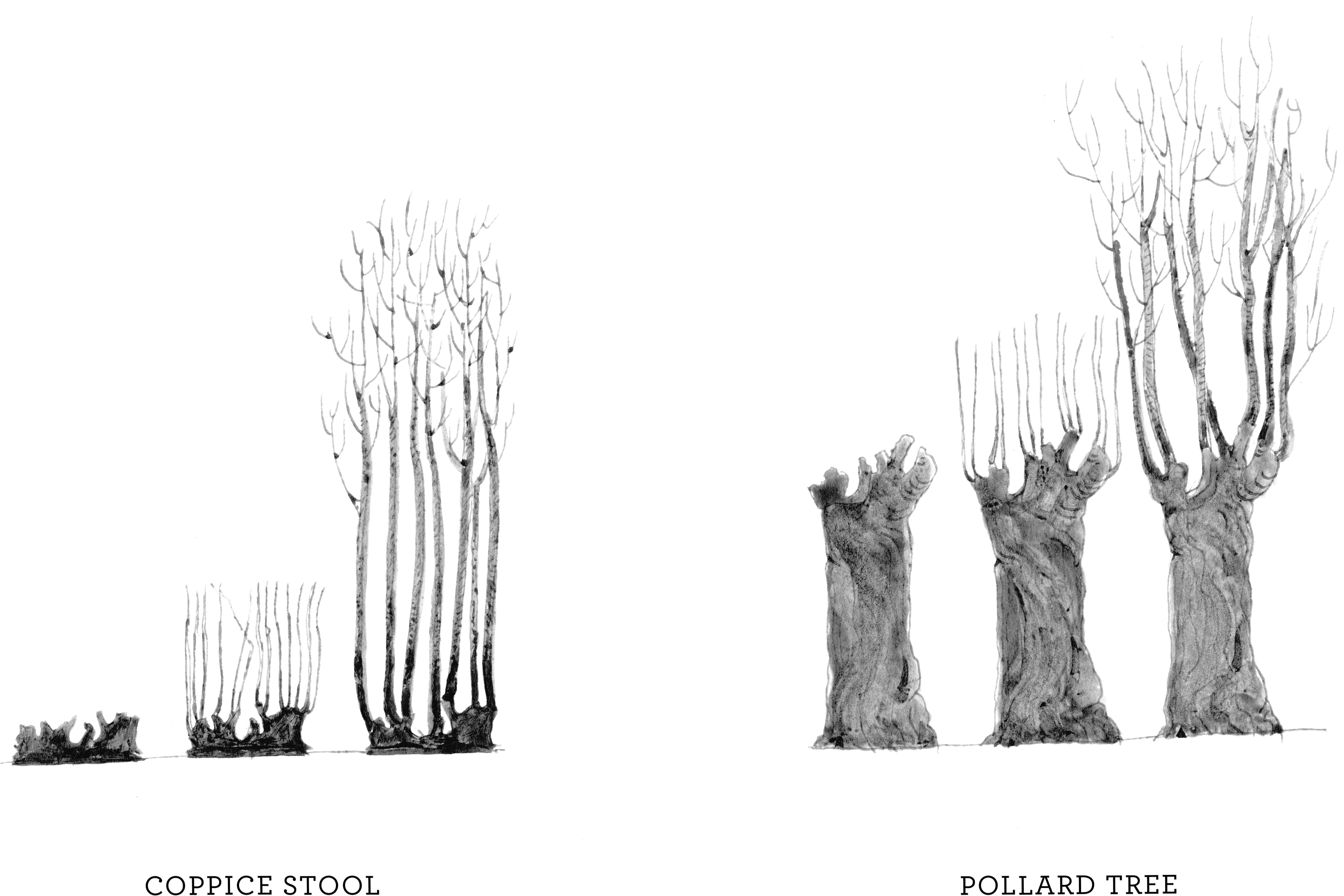

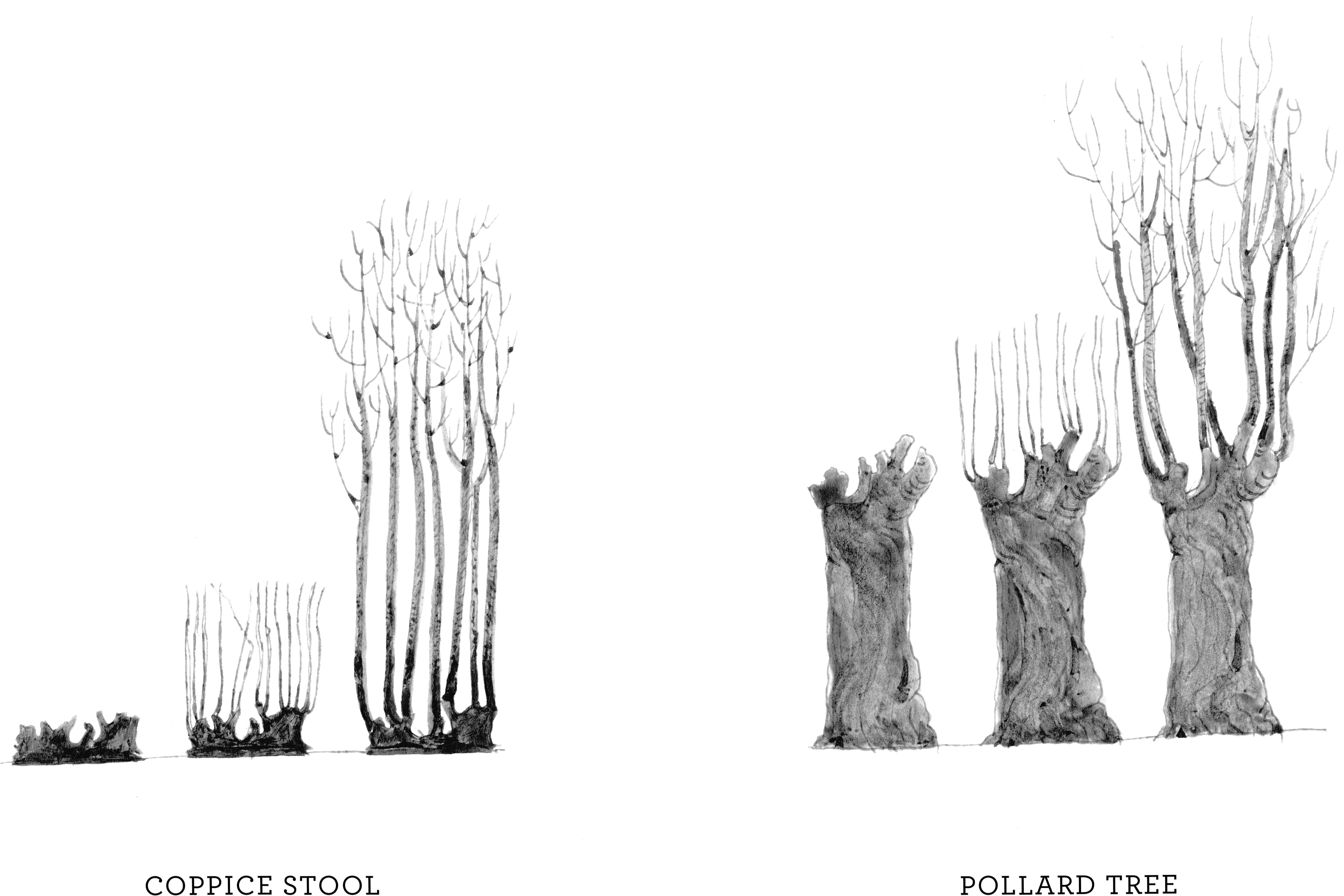

At left, a coppice stool, cut near the base. At right, a pollard tree, cut at about six-foot height on the trunk. In each drawing, from left to right, are new-cut, one-year-old, and five-year-old stems.

In many parts of the globe, however, cutting to the base was not a good idea. People depended upon their animals—cattle, sheep, goats, pigs—to concentrate the goodness in ephemeral grasses and leaves into a form that humans could eat. If you turned your animals loose in a new-cut coppice woodland, their mumbling mouths would munch the new sprouts as they arose. Once cut, your coppice would never come again, because every time it sprouted, the slender green new stems would go down the gullets of the stock.

One solution was to keep the animals out until the new trunks were strong enough to resist them. Ditches and banks, sometimes topped with hedging, were one solution. So were fences made of woven wood. A third idea did not require fencing. They called it pollarding. The word comes from “poll,” meaning to cut, crop, or shear, as in “polled Hereford,” a heifer whose horns have been cut off. The Hebrew prophet Ezekiel wanted the priests of God to be pollards: “Neither shall they shave their heads, nor suffer their locks to grow long; they shall only poll their heads.” That is, priests had to have haircuts. Because the hair is on the head, the word came to be used to describe an individual person, a pate, a head. The “poll tax” was a tax by the head, or the individual, and going to the polls is going to register the opinions of your individual head.

Pollarding a tree meant creating a number of “heads,” each of which would get periodic haircuts. To start a pollard, instead of cutting back to the ground, you pruned the trunk or the branches at a spot where the tree was at least six to eight feet tall, high enough that no cow or sheep or goat could stretch its jaws to reach it. You might cut right to the trunk, or cut back all the branches that were six feet or higher off the ground. If you first cut back to the trunk, it answered with a rosette of rising branches. Those branches became the scaffold on which to cut and cut again. Then, just as with coppice, you let the new sprouts grow for anything from one to thirty years, depending upon the size of the wood you want to harvest and the willingness of the tree to respond. As you continued to cut each branch at the same place, new sprouts emerged only from those blunt ends.

There were wonderful, graphic names for these strange, prolific, bulbous tips. The French called them têtes de chat, the Spanish cabezas de gato. Each meant “cat’s heads.” In English, they were heads or knuckles. The end of each branch got fat and thick. (On some species, it could get so large and heavy that it eventually threatened to break its branch.) The ends thickened because the tree responded intelligently to the cutting. It ceased to make new sprouts up and down the length of each stem, as would happen on an ordinary branch. Instead, it directed its buds to form and sprout only at the ends of each branch. There, hundreds of buds gathered, together with great quantities of starch to feed their release and their rapid growth. If you have seen a piece of furniture or a bowl made from burl, you have been able to look at the polished evidence of the thousands of swirling dormant buds that wait beneath the bark for their moments in the sun. A pollard head or knuckle is in essence a kind of burl, created by the mutual action of trees and people.

From the Mesolithic onward, at the latest, coppice and pollard not only supported human beings but changed their minds, opened their hearts, and instructed their hands. Food, fire, cooking, building, boundaries, bridges, and even ships all depended upon the twin practices. The more the people cut, the more they learned; the more they learned, the more they could imagine. As we shall see, the idea of springtime turned upon coppice; the eight-hundred-year tradition of classical Japanese poetry did too. The street, summer vacation, and homecoming all were invented in the cultures of coppice and pollard, but the most important thing that the trees taught people was to live in the presence of their days. You had to cut, all right, but you also had to know when to stop, and you had to learn how to wait before you cut again. If you failed in your response, it wasn’t that the authorities fined you or the editorials criticized you, but that you were cold and hungry in the coming year. Great Nature herself would punish you. For ten thousand years, trees were our companions and our teachers. They brought us this far, and perhaps they will carry us on. The only trouble is that we have forgotten almost everything they taught us.