If you haven’t got an instrument,

then play as best you can

upon the instrument of light

that fills the whole sky.

Miyazawa Kenji

Not far from Lars Grinde in the western fjord-lands, at the turn of the twentieth century, lived Nikolai Astrup. He grew up in the town of Alhus on Jolster Lake and lived all his life on its shores. He changed a precipitous hillside into a terraced farm, and he painted his family’s work and life there. I stumbled upon him because he drew and painted pollards. I became obsessed with his life. He is Norway’s most beloved landscape painter. Astrup, like Grinde, lived in the presence of his day. He conceived plans for his farmwork and his paintings, put his heart into their doing, and learned from his hands as he made them. Dirt, rock, plants, pigments, and canvas were his materials, but it was the light of western Norway that gave them life. In one sense, he was a rare creature, but in another he was exemplary. He showed how head, heart, and hand can make a full life out of unexpected materials, and how the difficult love of a place and its people can transform a person.

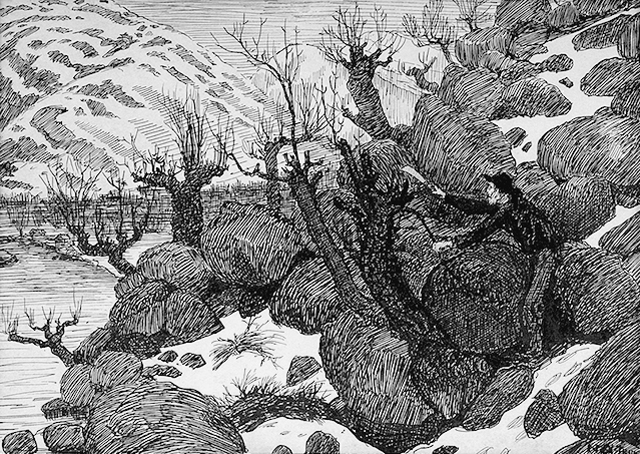

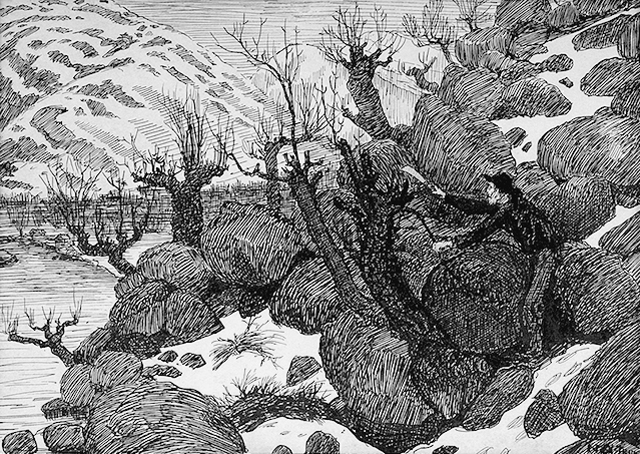

Nikolai Astrup’s drawing of a woodland of pollards on a rocky slope.

Astrup farmed to feed his family, and the family, the farm, and the mountain landscape with its pollards were what he captured in the light. In this, he closely resembled his contemporary Miyazawa Kenji, half a world away in northern Honshu in Japan. (Likewise, I had stumbled upon Miyazawa when I looked at coppice forests in Japan.) Both men considered farming a primordial art. At once poet and teacher of agriculture, Miyazawa wrote a poem in which an old white-haired man, with a stroke of a hoe, taught the farming teacher how to sow red turnips. “What brush stroke of ink painting, / what fragrance of a sculptor’s chisel,” he wrote, “could be superior to this.” When he wrote a poem of praise and challenge to a student who played the bassoon most beautifully, Miyazawa commanded the boy to learn to play upon the instrument of light. In other words, his art was not the fruit of its practice alone, but of a fully lived life.

At the age of twenty-six, Astrup fell in love with Engel Sunde, a fifteen-year-old local farmgirl. All of the Jolster district was scandalized when they wanted to be married, not because of the difference in their ages—in those days fifteen was not considered too young to marry—but because of the difference in their classes. Nikolai was the son of the Alhus priest, an upper-crust civil servant like the teacher and the sheriff. (Norway’s is a state church.) Engel was the daughter of a farmer, not a mere cotter—a sort of sharecropper—to be sure, but still a whole social rung lower than a civil servant. Astrup’s family was particularly troublesome. “I was just about done for when I met her,” he wrote, “and I owe it to her that my vitality flared up in me again, and the 15 year old girl, who followed me without fearing rumours, also gave me back my faith in human beings again, and why should I not marry her, despite the rumours and the talk in the family?” They were married the night before Christmas Eve, 1907.

They moved to the remains of a cotter’s farm, called Sandalstrand, reached only by a precarious flight of stone straight up a steep slope. The long stairway was about as wide as the average doormat. When you walked up or down it, you had to keep your feet together, or you would fall off. The first time Astrup climbed the steep stairway, he noticed that if you dropped something, it rolled down the hill until it fetched up in the alders at the lakeside. The last direct sun hit Sandalstrand around the first of October. It did not return until the middle of March. There were two small houses on the property, but the rain came in the roofs.

The first thing they needed was a way to get home. Astrup carved a three-turn switchback path from the lake up to the cabins, wide enough for a horse and a cart, and gentle enough for them to get up without losing their breath. Part he dug into the hill, part he supported on stone and dirt foundations. It took a year to build it. Three fast streams came through the property. He dug deep channels for them and made bridges over the path to prevent erosion. He dug out a pool by the place where he planned a barn, in order to keep milk cool.

For his family’s private gathering place—he called it the Grotto—he pollarded a linden and a willow, training the sprouts to cover the flat terrace at the back of which he installed a fire pit in the hollow beneath a rock. Nearby were a pair of goat willows that he twined together when they were young, so they grew up in a strange embrace. Below the houses rose tall birches that made the family think they were living like birds in the treetops. “In spring,” he wrote, “it is lovely to have the windows open here, and hear the song thrush outside in the treetops.”

He planted extravagantly, both to feed the family and to keep the steep slope from eroding away. His first nursery order contained 451 fruit trees (apples, sweet and sour cherries, blue, Victoria, and Mirabelle plums), 611 berry bushes (raspberries, black currants, red currants, gooseberries), 100 rhubarb plants of ten different varieties, and 500 vegetables. He might have fed an army of frugivores, if not for the beast he called “the devilish hare.” Of the hundreds of fruit trees that he planted in 1914, not more than 50 were still alive a decade later. The price of this purchase amounted to a tenth the cost of the whole property.

To present this botanical menagerie to the sun, he built almost two dozen terraces on the slopes above and behind the houses. The tallest terraces rose almost thirty feet from the land beneath them. Others made small fields a mere five or ten feet above their neighbors. Into a small terrace on top of the tallest hummock, he built a cold frame to start the vegetables. Dynamite, dirt, stone, and three years’ hard work put them into shape. He did not like bare stone walls, so he clothed the retaining walls with sod, each tranche held in place with posts driven through peat blocks. It was not simply an aesthetic choice. Astrup appears always to have been thinking of the sun, not only what it could give but what it might take. He reasoned that covering the walls with grass would reduce erosion when the torrents of spring came at last, and that the clothed undergirding of stones would shift less in the freeze and thaw. He edged all the terraces with berry bushes—currants and gooseberries, chiefly, tough stringy bushes that sent out explosions of clinging roots into the erodible edges.

One of Astrup’s greatest interior paintings at Sandalstrand shows Kjokkenstova, what was for years his family’s main house, on Christmas morning. A young daughter—the couple eventually had eight children—stands on a backed wooden bench leaning over a table filled to overflowing with colored fruits. The window behind frames the table and the lake beyond. It is a spacious and encompassing picture. Looking at it, you would never guess that it showed almost the entire inside of the house. Here was a microcosm of the family’s life. They lived in a mountain-enclosed land, with a short growing season, using tiny growing plots, and in a very small community, where neither of them fit the expectation of what they were meant to do and be. More than once, Astrup wrote to friends that he would give it up and move away, to Denmark or to somewhere even more cosmopolitan, but he never did. Almost grudgingly, he wrote, “I have become fond of this farm, where I have taken on so many heavy tasks.”

Looking from the fields above the dwellings at two of the three principal houses at Sandalstrand and Jolster Lake below.

Ingeborg Mellgren-Mathiesen, a fine garden maker working to restore the Astrup property, said, “He never called Sandalstrand a garden. It was always ‘the farm’ or at most ‘the farm garden.’ ” Astrup delighted in the contrast between the huge red-stemmed leaves of his many rhubarbs and the delicate white flowers of the cherry trees, and he painted them, but he was equally pleased by the food that they produced. His aesthetic pleasures were woven together with the work and the fruit of his days. The outdoor paintings at Sandalstrand often show his family on the terraces, making rows in the vegetable patch, planting seeds, cutting rhubarb, harvesting mushrooms.

They waited and waited for the coming of spring, when at last the sun would shine on their faces again. In 1921, Astrup wrote to a friend, “We are living here on the ‘shady side’ of the lake—and when after almost half a year’s absence the sun begins to appear—then we move into a permanent sunfilled yearning for the ‘other side’ of the lake, where people have already long been living in the sun’s magic above the thawing slopes and snowy mountains, while over on ‘this side’ we are in shadow all day long—or maybe just get a glimpse of the sun for a couple of minutes each day.” They would walk down to the beach and touch a little of the snowmelt along the thawing shoreline, just to assure themselves that it was really happening. “We begin to think that we too here in the shadow side will finally have spring—the air is full of catkins—you feel that spring is coming as through a cobweb of branches . . . the rushes are already sprouting—and even the old alder trunks have enough sap to bleed one last time.”

Spring brought holy beauty and a hard day’s work. The change was explosive. Everywhere in fjord country, one of the first signs of spring came not to the eyes but to the ears. Sun high on the slopes started the melt. The short, steep-tilted streams and waterfalls—quiet in the gray of winter—woke up and thundered. Everything had to be done at once. Fields had to be manured with what the animals had made in the barn over the winter. The pollards had to be pruned. Cabbage, potatoes, beets, turnips, radishes, swedes, carrots, lettuce, onions, peas: the seed had to be sown or the seedlings that had been started in the cold frame mound set out, the potato eyes cut and planted. Gooseberry and black currants on the terrace edges had to be checked, pruned, and replaced if necessary, before erosion could start. Lambing ewes filled the barn. Winter damage to the fruit trees had to be pruned. The raspberry terrace and its two hundred plants had to be tended to and pruned. Damage to the big path had to be repaired. The roofs had to be weeded. The perennials like rhubarb had to be checked to make sure they were sprouting and perhaps dosed with just a little spare manure. It was not a gentleman’s farm.

The coming sun woke the land so quickly it seemed miraculous. Astrup wrote Per Kramer in the spring of 1920, “Everything was changed in these two days—the apple trees were almost fully sprung, and the cherries and plums in full bloom, rhubarb leaves got twice their size in just two days.” He suddenly had not only to plant and tend the farm garden, but to paint it. “Motifs were everywhere,” he wrote. “I didn’t know where to start painting.” Every year, it must have been delightful and utterly exhausting.

Rhubarb if any was his favorite plant. His first nursery order included 100 plants of ten different varieties, including the immense-leaved Chinese rhubarb and the popular cultivars Victoria and Monarch (both still available today). He asked for one cultivar that he claimed grew only in the king of England’s garden. A great painting shows Engel in a print dress picking rhubarb. She and the red leaves fill the canvas, a delicate white flowering cherry to their left.

The marriage of an artist and a farmer was a strange one. Both sides of society looked askance. Not only that, the fact that a priest’s son had become a painter and a farmer and that he made and drank wine, where his father had never touched a drop, caused people to shake their heads. Out of that difference, however, the family created their place. Astrup loved to tinker. He confessed that he had the bad habit of crossbreeding plants to see what might come of it. (He had a fence-enclosed nursery terrace for the purpose.) Many of his creations died on the vine, but he was particularly proud of the cross he made between the Victoria and Monarch rhubarbs. This unnamed hybrid was the variety he preferred to use to make rhubarb wine. His wine was first popular among his friends, both those from the local community and visitors from far away. He began to give it to people for their wedding feasts, and soon it was in demand all over Jolster.

The Astrups shared produce with their neighbors, both giving and receiving. Even if only fifty fruit trees survived, the fruit and berry produce of the farm was far more than even eight children could eat. They gave fruit to neighbors. They propagated and gave gifts of plants. It became known around the lake that Astrup loved the old-fashioned Jolster plants, as did many of the farmers. When new drainage projects threatened the beloved marsh marigold, he got plants from the neighborhood and tried to keep them at Sandalstrand. When new improved swedes appeared, he championed the old flat ones, collecting them and growing them in his garden.

The Astrups designed village banners for parades and festivals. On one occasion, Nikolai was asked to design a wedding apron, the indispensable centerpiece of a fjord-land wedding dress. He complied, and he suggested that Engel print and make it. For decades afterward, the designs made by Astrup and created by Engel were a main source of wedding aprons in Jolster. From being the couple of a scandalous marriage, they became—through their wine and their wedding aprons—a part of almost every wedding in the district.

Head and heart alone do not cross the barriers of mistrust, but hands do. When they began at Sandalstrand, Astrup and Engel were ostracized. When he died of complications of lifelong asthma in 1928, the entire lake came to his funeral. Indeed, the people of Jolster paid for it.