My obsession with sprouting and with the antiquity and scope of people’s life with trees had taken on the quality of a quest. Everywhere I went, someone sent me further. While I was talking to the Indians about fire coppice in California, someone told me about the culture of coppice oak forests in Japan. They said that classical Japanese culture had been based on coppice woods. It was shocking news to me. Off I went.

In ancient Japan, there were thought to be five elements, not four. Earth, air, water, and fire were four, just as in the West. The fifth element was wood. “Fire cannot sustain itself,” reasoned a seventeenth-century shogun. “It requires wood. Hence, wood is central to a person’s hearth and home. And wood comes from the mountains. Wood is fundamental to the hearth; the hearth is central to the person.” It is hard to put it clearer than that.

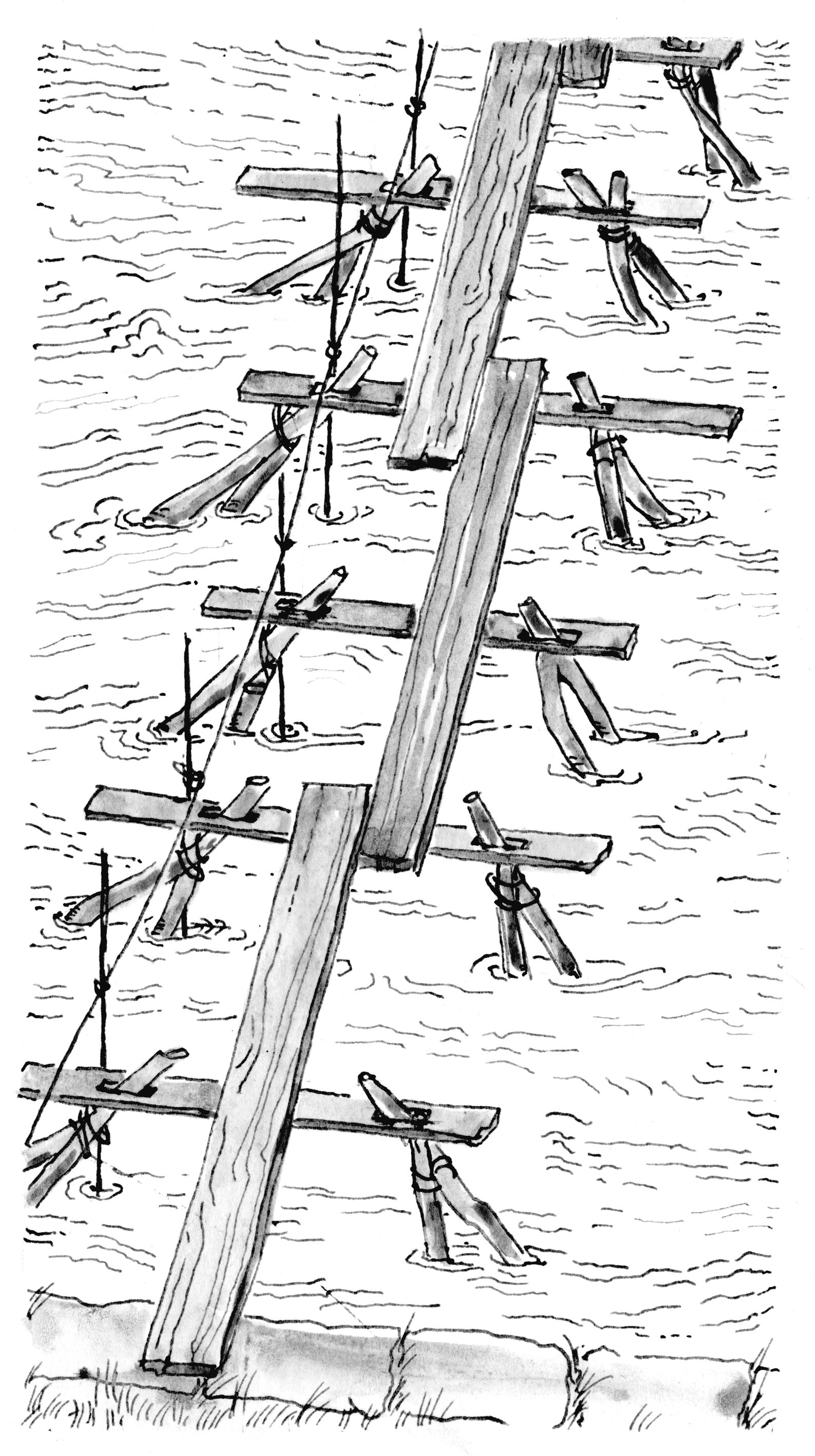

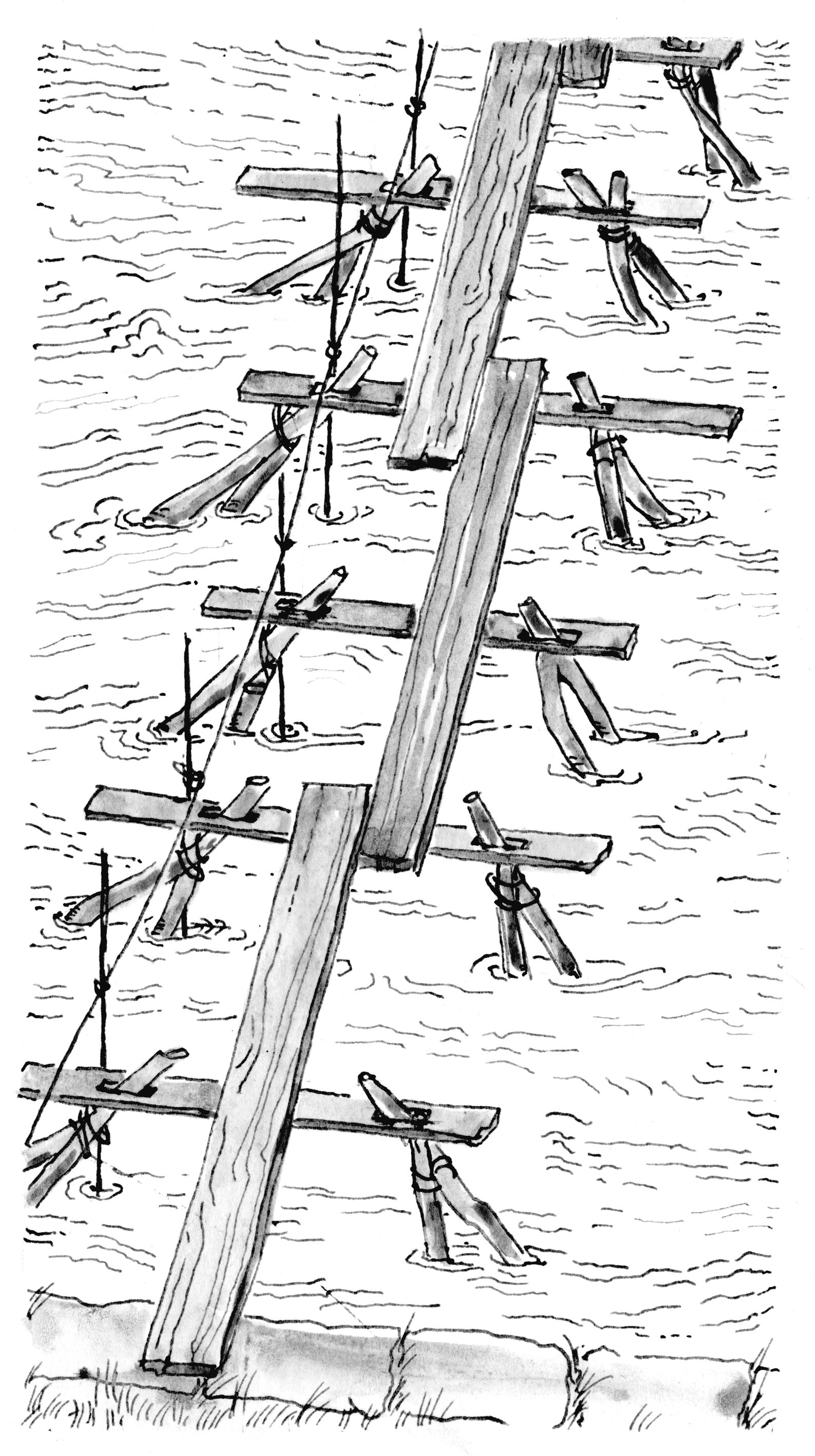

Near the town of Tono in Iwate, a winter-cold northern prefecture on Japan’s main island, stands a footbridge across the Kesen River. At first glance, it looks to have been made by an idiot. There are nice broad cedar planks for a walking platform, but they are not joined end to end. Instead they are in three sections, each butting against another section simply by placing the two ends beside each other, overlapping, on a support. So you walk a straight line, then sidestep, then walk another line, then sidestep back, and finally reach the other side, about two hundred feet from the start. From the air, it would look like diagram of a dance step. The piers themselves stand in the water like the jointed legs of insects. Upside-down coppiced crowns of walnut and chestnut flex as though about to pounce in the river bottom, each piece on two or three legs, the former crown branches of the coppice. These spider legs run in rough pairs across the river. Joining each pair as a pier cap or headstock is a planed board that is mortised to receive the tenoned trunk of the trees. The walking platform is simply laid atop these and a bamboo rail is lashed along one side. The bridge has been there—well, sort of—since about the seventeenth century. It is called a nagereba bridge.

A Nagereba bridge, showing the deck planks, the crosspieces, and the coppice piers.

Nagereba is an inflected form of the Japanese verb nageru. Kenkyusha’s New Japanese English School Dictionary gives the definitions as follows: “throw, hurl, fling, cast, pitch, toss, thrown down, or throw away.” The inflection gives roughly the meaning “In case it should be thrown down, hurled, flung, cast, pitched, tossed. . . .”

When a big storm hits, if the water is high and rough enough, the nagereba bridge comes apart. Like the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz, its legs go one way, its headstocks another. The big planks of the bearing beams are tethered to the shore. They turn to mime the stream flow. The river rushes over them until the storm is over. Then out come the townspeople from both sides. They look for the piers and the headstocks. If they need to, they cut new ones. They reel in the beams. Working as a team, they put the bridge back together.

Nagereba mo. If it is thrown down, put it back.

About six hundred miles away in the city of Kyoto is the Philosopher’s Path, a lovely creekside walk that leads tourists from one stately temple to another. In the great Zen temples, the gardeners rake parallel channels of sand around the islands of selected rocks; they match moss floors and canopies of pale green maple leaves. They have no compunction about treating those Japanese maples just as the country people do their trees to make the nagereba bridge piers: Where they want new branching to ramify a crown, they make selected pollard cuts on the ends of branches. And bang, back come three or four new branches, sprouting just behind the cut. On the ground beneath, they rake away dirt and channel the moss, so the root tops are exposed. Crown and root do not mirror but reflect each other, showing their similar idea and different execution.

My wife, Nora, and I were walking that Kyoto path. We were completely exhausted from temple viewing. Each place was so grand and so perfect, even in its smallest corners. I envied several of the pruners I saw. They simply carried their homemade tripod ladders from one tree to another for their whole careers, meticulously snipping and shaping their one astonishing garden.

A small bridge across the stream had a sign pointing to a jinja, a Shinto shrine. It was uphill all the way, we sighed, but why not? It might prove a change of pace.

Shinto and Buddhism were formerly commingled in Japan, but in the modernizing Meiji period, the Japanese decided to forcibly separate them. Among the bad results was the strident deification of the emperor, who—though in fact a puppet of the rising military oligarchs—was represented as the god figurehead under whose banner the nation was to go to war. It was also the Meiji sages who imported the word “religion” to Japan. (It first appeared in a commercial treaty with the Germans in 1868.) Prior to this time, there were Shinto gods in Zen temples and Buddhist deities in Shinto shrines, but no one thought to sort it out or to call any of it “religion.”

We struggled up the hill, with one or two rests. (At one house, I saw a simple combination of two hydrangeas and one nandina, making a lovely front garden, no larger than a love seat, out of modulating whites, reds, and greens, with short, fat light green leaves mingled with sharp-spear-tip dark green ones.) Finally, we came to the torii gates that led to the very edge of town, where mountain meets houses. Each Shinto shrine is guarded by a pair of spirits, one standing tall with its mouth open and the other seated with its mouth closed. These are meant to show the two ways of resisting evil: by attacking and defeating, or by enfolding and converting. The deities are often lions, dogs, or even foxes. Here, however, they were mice.

Nezumi-sama. Komanezumi. Honored mice. Guardian mice. In the beginning times, a prince fell in love with a beautiful maiden. Her jealous father told the young man to fetch an arrow that he had shot into the middle of a field of grass. As soon as the suitor set out, Dad set the field on fire. As the prince was about to be consumed, a mouse appeared and gave him entry to her hole. The fire passed harmlessly over. (This, by the way, is the best hope to survive a wildfire: Dig a shallow hole and lie down. It is still taught to woodland firefighters around the world.) As soon as the flames passed, the mouse handed the prince the arrow.

At this shrine, one of the mice stands with her mouth open and what is interpreted as a sutra scroll held in her forepaws. The other is bowing, closemouthed, over something that looks like a child’s top but that is said to be a sake bowl. The latter augers a healthy baby, long life, and luck. Young lovers and expectant mothers often pray here. The same thing happens at a church in the South of France dedicated to Mary Magdalene. Young wives go there to scrawl upside-down Us on the dark, damp wall of the crypt where the relics of the saint are enshrined. Within it, they scratch vertical lines, one for each hoped-for child.

In the South of France, things became sacred by association with the holy ones of scripture. In Japan, there was in theory nothing without a soul. Rock, river, hill, cave, tree, fox, mouse, chicken, man, woman, smallpox, cancer, and the cure for cancer: all had been enspirited. Often in the larger shrines and sometimes even in the countryside, one comes upon ropes made of a white paper folded into streamlined quadrilaterals like cartoon lightning bolts. These may be wrapped around an immense Japanese cedar (a cryptomeria), a small boulder, a statue, a lamppost, or the street where a procession will pass. They are most often seen within the precincts of shrines, but sometimes also in the landscape. Each signals that in that place a kami is among us.

There is no shortage of different kami. One shrine in Tokyo is said to enshrine more than 2 million of them. They are not transcendent gods or abstract spiritual entities. It is in fact hard to say just what they are. They are a little like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle for quanta: you can’t simultaneously fix their location and their path. They are perhaps the energy by which a thing acts among other things. “Energy is eternal delight,” wrote Blake, always and only expressed through a particular thing, place, or person. Kami may be grand in their effect or almost trivial: A pair of these kami is said to have created Japan and all that is in it, for example; another kami is said to cure (and yet another to cause) toothache.

People then cannot act as a realm that is apart from nature. Everything has spirit, energy, and everything is enmeshed with everything else. The Japanese are therefore not shy about acting on the world around them. There is little thought of a pristine Nature, apart from human beings. Praying to mice is one aspect of this way of living. So is the deep pruning of a tree. The nagereba bridge is another: It is not superior or inferior to the natural world. It is part of it. The overwhelming energy of a big storm takes it apart; the enfolding energy of the townspeople puts it back together.

The shrine of the nezumi-sama sat on the very edge of Kyoto. The roads led down from it, but above was steep, untracked woodland. (There were in fact a number of makeshift plywood and metal barriers behind the shrine to keep the one from flowing down onto the other.) Almost every shrine, except for some at city centers, is so located: on the edge between steep and level ground. Such land is not hard to find in Japan. Seventy percent of the rural landscape consists of short, steep mountains with narrow valleys at their base. It is the signature landscape of the countryside, and from it a people was made.

No one knows when rice was first grown in paddies in Japan. The technique certainly came from China and from Korea. Perhaps it came not once, but a number of times. The first evidence of a rice paddy in Japan dates back 6000 years, during the Neolithic Jomon period, but not until about 2500 years ago did it become the normal and pervasive way to grow a staple food so important that the name for any meal is gohan, which literally means “rice.” The phrase for “peace and prosperity” is gokoku hoojyoo, which means “a good rice harvest.”

Though the farmers complain that people are now abandoning them for horrible things like croissants, spaghetti, and buttered bread, it was still remarkable to see the extent of rice paddies through the entire countryside. A broader valley had them by the dozen, a narrower one had all that would fit, and even the narrowest defile between canyon slopes had one or two. The lower part of a steep coastal slope might be terraced into a brocade of paddies descending the hill in stages. Even in the small towns, instead of a garden beside the house, four times out of five there was a paddy. The strangely modulated green of them—winking lighter and darker as the light on the water comes and goes—becomes a part of your eyescape. When the color and sheen of them is absent, you think that something has gone wrong.

For at least two millennia, the paddy field has been at the center of Japanese culture, but it did not stand there alone. The grasslands beside the paddies were regularly harvested for thatching, for bedding, and for fodder, and the trees on the woodland slopes fueled and warmed the villages. One poem in the ancient anthology Manyōshū calls Japan “the rice-abounding land of reed plains.” Rain falling on the hillsides soaked into the ground through the trees and the grasslands, emerging near the bottoms in springs, the indispensable source of water to keep the paddies wet. The hills served as reservoirs of groundwater. The growing trees—mainly the two Japanese oaks, konara and kunugi—trickled the water off their leaves and trunks into the dirt. The water percolated into the ground instead of running off. The farmers took up the fallen oak leaves and the grasses, either composting them directly or feeding them to their draft animals. The manure and compost went into the paddies as a fertilizer, all that was needed to supplement the nitrogen supplied by the blue-green algae and the fish and frogs and other animals living in the water.

Before the people ate the rice, they cooked it over charcoal made chiefly from the konara and kunugi oaks. They coppiced a part of every hillside every fifteen to twenty years, cutting back a section of the trees to a few inches above ground. The woods were called the booga mori, the forests of sprouts, the sprout lands. As the trees grew back, different plants also sprouted among them, some brought in by birds or the wind, some from the dormant pool of seeds. It was not an impoverished landscape but as rich a land as the place has ever known. Where uncut woodlands have about 176 different species of plants living in them, the whole mosaic of the booga mori has 351. It is twice as diverse as an untouched forest.

The tree roots stayed in the soil to hold the water and feed the springs. The trees quickly sprouted back. The cut wood went for firewood or for charcoal. (In 1940, the woods still yielded 2.7 million tons of charcoal.) The brushy tops might be kept for fire starter, used to dry sea salt, or even thrown into the water to make habitat for fish or oysters. Some of the trunks were cut into logs, each inoculated with mushrooms. Year by year, people would cut another section, so there were always parts of the woodland in different states of growth. It was a way to make edges, and edges within edges, multiplying the conditions in the landscape, so creatures that loved different habitats all could thrive. In the new-cut lands, the giant purple butterfly (now the national butterfly) lived, along with stag beetles and longhorn beetles, both prized as pets by children. Dragonflies cruised the paddies and the grasslands, straying into the open young forest. Rice fish, frogs, and freshwater molluscs inhabited the paddies. Bumble bees and wildflowers coevolved, so that the order of flowering and the shape of the flowers corresponded to the time when different bees and different bee life-stages were present. The flowers were long and wide when only the bumblebee queen was gathering pollen and short and fat when the smaller workers were out and about.

As the trees grew in, overhanging the paddies and the rice fields, the gray-faced buzzard and the golden eagle perched atop them, waiting for frogs to reveal themselves, harvest mice to nest in the waving grasses, and rabbits to run across a new-mown field. As the grasses grew back and the rice matured, the birds moved into the woods to hunt. Eighty-five different butterfly and moth species fed or reproduced on the regrowing konara and kunugi. The two great songbirds of Japanese poetry—the springtime uguisu and the summer-visiting hototogisu—both live in the regrowing coppice and in the tall grass. When you walk on a paddy edge in June, the call of the hototogisu is sometimes almost constant, along with the last songs of the springtime uguisu, whose song is said to name the Lotus Sutra.

The youngest sprouts—growing in discrete mounds like a colony of tortoises—shared their sunny space with wildflowers and grasses. The people enshrined those they most valued. The sacred rope around them was made out of language. The Haru no nanakusa (Seven Spring Herbs) were gathered for a New Year festival, Nanakusa no Sekku, on January 7. These were the first herbaceous sprouts of the coming spring. People ritually laid out their cooking utensils, sang a song, and went to hunt the plants. They made the catch into a tart soup.

The first sections of the Kokinshu and the Shinkokinshu, two of the principal imperial poetry anthologies, each have more than a dozen poems about going to pick the wild spring herbs. Even today, there is a great deal more seasonal wild food available in Japan than in most other developed nations of the world. Tempura is often made with wild herbs of the paddy, the cut grassland, and the coppiced hill. Yamaudo, taranome, and koshidowa are three whose stems and leaves are battered and quick-fried. Taranome in particular is valued for its tart, almost astringent flavor. The bulb of katakuri, a trout lily that grows in the new-cut woods, is powdered to make a starch to coat and to thicken other foods. The little purple trumpet flowers carpet the ground in early spring under the regrowing coppice.

The Aki no nanakusa (seven autumn grasses) were likewise crucial for both cooking and culture. Among them, the hagi was used to flavor rice or made into a tea, and the kuzu root was ground and used to thicken foods. The glory of these plants, however, was their place in Japanese poetry. In all the great imperial anthologies, the defining classics—the Manyōshū, the Kokinshu, and the Shinkokinshu—the autumn flowers are keys to the season.

They are among the chief kigo, or season words, by which autumn is announced. Hagi, the bush clover, droops gracefully, but sprouts with wild abandon. It was admired for its feminine grace and its perennial fruitfulness. It flowers white even as its leaves are reddening, just as the deer call to their mates. It became a symbol of mono no aware, the evanescence of life and love. The plant appears in 137 autumn poems in the Manyōshū, and in many more in the later anthologies. Ominaeshi, the yellow, fragrant maiden flower, was celebrated for scenting the autumn air and for its waving blossoms. It reminded people of love in autumn and even apparently tempted Buddhist priests to ignore their vows of chastity and nonattachment. A great poetry contest of the Heian period was called the Tenjinoin Maiden Flower Contest.

Here and there in the anthologies, the coppiced oaks themselves appear. The coppice forests were called hahaso. In one poem the mountainside woods were called Hahaki, a pun, or kakekotoba, meaning both oak woods and mother woods.

This landscape of dynamic edges has recently been dubbed satoyama, marking the interface between sato (village) and yama (mountain). So central to the Japanese was this kind of place that when commoners were required to adopt surnames at the end of the nineteenth century—the better for the Meiji modernizers to be able to tax them—the majority chose names that located them in the satoyama landscape. Tanaka was from the middle field, Shibata from the firewood hill, Ikeda from the paddy pond, Kimura from oak wood village. Nishimura came from a village west of there, and Hasegawa lived along the river in the long valley. Yamaguchi lived where the road climbed into the mountains, Morita by the field at the woods’ edge. Maeda lived by the first field out of town, Yamada by the field deepest in the mountains. Takata was from the highest field, Yamamoto from the hill bottom. Koyama lived by a little hill, Takayama by a tall one. The west river of Nishigawa fed the west field of Nishiyama. Oohira and Hirayama came from the broad reed plains. In a hard rain, Uchida got dirt that came down the channel from Ueda’s field above. Wada came from a quiet field and Honda from the center one. Kawasaki lived near the river mouth, Nakagawa in the middle of it. Takagi lived by the tall tree. Kozawa’s field was by the little swamp, and Hamada’s field was on the seashore. A third of the one hundred most common Japanese surnames have either yama (hill or mountain) or ta (paddy, rice field) in the name.

In Japan, the field and forest together created a culture that endured for two and a half millennia. It was not without problems. Early, in the AD 600s, the rise of metallurgy and its need for abundant charcoal seem to have led to overcutting of the booga mori. Some woods were lost, and erosion ruined rice fields. The people put the forests back. A document in AD 821 commented, “The fundamental principle for securing water is found in the combination of forests and trees.” People learned what they could and could not do. In the late Edo period, before Japan opened to the West, rising population led to overexploitation of the forests. The result was the same. The Meiji authorities reined in the excess, and the satoyama recovered.

The third time the coppice woods have been threatened is the present. After World War II, Japanese culture was itself in ruins. Petroleum came into the burned land like a miracle. You could heat the house with it and cook with it. You could even fertilize the rice fields with it. Who needed that laborious old booga mori? Who needed the hahaso? Indeed, who needed the Manyōshū, the Kokinshu, and the Shinkokinshu, silly elitist books? Let’s get people off the land and into the factories! We will become instantly modern! We will have all kinds of stuff! Instead of destruction and starvation.

The booga mori declined rapidly. Annual charcoal production dropped 99 percent, from 2.7 million tons in 1940 to 28,000 tons at the turn of the century. During the 1960s and 1970s, around the big cities, satoyama landscape was turned into new towns and suburbs at a rate of 150,000 acres per year. The area of coppice woods around Yokohama, for example, declined by two-thirds between 1960 and 2005. The Japanese had always prided themselves on being self-sufficient in food. To this day, farmers as a group are protected, and designated farmland can only be bought and sold among farmers. During that same period, however, the ability of the Japanese to feed themselves dropped from 73 percent to 34 percent. And when the coppice woodlands were not urbanized, they were often converted into plantations. Huge tracts of land in rural northern and western Japan were converted from konara and kunugi to Japanese cedar and red pine, marketable timber.

Tama New Town was the archetype of postwar development. To prevent the chaotic suburbanization of Tokyo, as thousands of people moved there, the metropolitan government in 1965 began a meticulously planned project to convert the Tama Hills, twenty miles from the center of the capital, into a network of connected suburbs. Heretofore, it had been almost entirely satoyama landscape. To make the apartment buildings, malls, stations, and parking lots, they cut the tops off mountains and dropped the dirt in the valleys, making flat heights for building and flat bottoms for parking. In 2017, Tama New Town was eight miles long and two miles wide. A quarter of a million people lived there.

Tama Center is its commercial hub. The train from Shinjuku station takes you there, and from there you can fan out on suburban buses and rail lines. Don’t try to walk, however. You cannot cross the street from the station to the mall with its high-rise hotel unless you go up and down half a dozen flights of stairs. Barriers prevent pedestrians from simply walking across the street. This was not an accident of development, but a thoughtful scheme on the part of the developers. For safety’s sake, they decided to keep the human and vehicle traffic separate, but the vehicles did not have to struggle up and down stairs. We people did.

My wife and I made the crossing one Friday in June. Once across, we stood in the remains of a satoyama. It was now called Parthenon Avenue. A wide masonry pedestrian mall bordered by two raised beds with about fifty trees, it was flanked by hotels, department stores, and shops. It sloped up, just as it did when it was hahaso, but at the top, instead of a mountaintop, was a parody of a parody: a three-bay set of concrete uprights topped with concrete plinths. It was hard to tell if it looked more like Stonehenge, an exposed building foundation, a Greek temple entry, or a shrine gate. Mussolini would have been proud of it. Tama Center is known as the City of Hello Kitty. The chief crossing avenue leads to the Sanrio Puro, a Hello Kitty–themed amusement park. On this summer evening, the sunset was obscured by the imitation rainbow arch that invites you there. Schoolgirls in their white shirts and black skirts trooped in and out.

There were once more than 350 plant species in Tama’s woodland. Now, in Tama Center, there were maybe 10 or 12, all disciplined to fit inside the long planter beds that flank that paved avenue. On the other hand, there were thousands of different products for sale. The Mitsukoshi department store alone had an entire floor of restaurants. They had traded one diversity for another: given up the dynamic and living diversity that depended upon intelligent human interaction to maintain and preserve it, in exchange for a vast selection of goods. Where you might have had many different roles in a satoyama—forester, farmer, basket maker, bamboo shoot collector, mushroom farmer, mochi maker, potter, blacksmith, collier, homemaker—there were only three on the Tama Center mall: buyer, seller, or support staff. It was a terrific department store, but somehow it didn’t seem like a fair trade.

Many Japanese agreed. There were protests in the streets. Two great anime movies arose to defend the satoyama. One of them, known in its English release as Pom Poko, though in Japanese its title means The Heisei Raccoon Dog Wars, was actually a saga about the building of Tama New Town. The tanuki, or raccoon dog, is a small mammal that in Japanese legend is adept at transforming itself into other creatures. The film recounts the efforts of the tanuki to prevent the destruction of their habitat by the rapacious humans. This is the best place to see what Tama looked like as a satoyama: there are anime scenes that clearly show the coppice woods and the rice fields together. In one scene, all the tanuki together exert their shape-shifting powers to transform the brand new high-rise suburb back into satoyama. The people looking out their apartment windows are delighted and surprised. One recognizes her mother on a village path. But the effect is temporary.

The second movie is the most popular film ever made in Japan. My Neighbor Totoro tells how two young girls and their father move to a small farm house in a satoyama village not far from Tokyo in the Sayama Hills, to be near the mother, who is recovering in a sanatorium. There, the girls—first four-year-old Mei and then her eleven-year-old sister, Satsuki—meet a gigantic purple egglike creature whom Mei dubs Totoro. (There are also smaller Totoros running everywhere, as well as living herds of charcoal dust.) The girls first meet Totoro together on a rainy evening when he appears beside them at a bus stop. The girls lend him an umbrella. He loves the way the rain sounds when it patters and pelts on the canvas. He appears to think they have given him a musical instrument. Their father says that the girls are lucky. They have met the spirit of the forest. When Totoro helps them, they go to the largest tree in their woods to thank him. My Neighbor Totoro is exactly about the spirits infused in the living world. The Totoro are kami. In the antidevelopment protests, it was often a Totoro banner that led the way, and one rallying cry was “If you destroy the satoyama, we will no longer be Japanese.”

Who were they kidding? Or perhaps it was not such an exaggeration after all. If you took away the rice fields, with their calling frogs, their rice fish, their sansai for seasonal gathering, their hunting buzzards and eagles, their planting, growth, and fruiting; if you took away the coppice woods, with their woodcutters, their singing uguisu, with the seven spring herbs and the seven autumn grasses, with the red autumn leaves of the hahaso; if you took away the grasslands with their annual cutting or burning, their hototogisu singing, the harvest mice swaying on the stems, then what remains to connect a people to their own story?

In the early tenth century, the poet and compiler Ki no Tsurayuki wrote the preface to the Kokinshu. “The seeds of Japanese poetry,” he said, “lie in the human heart, and they sprout the countless leaves of words.” To describe what people see and hear around them, he asserted, was the way in which poets could sing the feelings of human beings in the round of the four seasons. People were not the only singers. “When we hear the call of the uguisu in the cherry blossoms or the voice of the frog in the water, we know every living being has its song,” he continued. If the voices of the creatures were stilled and the words of the poets faded into the barely remembered pastel once-upon-a-time, then where were the Japanese? What would become of the words that could “move heaven and earth, arouse the kami and the spirits, calm the relations between men and women, and pacify the hearts of fierce warriors,” when the things that they referred to were no more? Are the contents of a Mitsukoshi department store, lovely as they are, enough to make up that loss?

Many Japanese have thought not. From protest, they went into action. They had the model of the Nagereba bridge: “Nagereba mo,” “If it is swept away, put it back.” The volunteer movement began in the very shadow of Tama New Town, at Sakuragaoka Park. A concession to the citizenry, the park opened in 1984. It was all hill and valley, all former coppice woods and rice paddies. If you walked into the woodland today, you would see hundreds of kunugi and konara that have not been cut for more than half a century. Each of their multiple sprouting trunks are now as big around as a barrel. If you were to cut the trees again, they might not answer well. They have been let go for too long. The forest they have created is now dark.

In the sun on the edge of one such wood, however, were three long garden beds. Each was planted with the perennials and shrubs that once grew in the satoyama here. The plantings were separated into the three seasons of flowering: spring, summer, and autumn. It was a study garden. Members of the Sakuragaoka Park Volunteers, a group founded in 1990 and now numbering about eighty-five members, learn their plants here, so when they go to restore the woodland, they know what not to cut.

That Saturday morning, when I went to meet them, their room in the park office was a forest of human sounds: scraping of chairs, sharpening of tools, footfalls, giggling, passing woodland gossip, greeting the visiting gaijin (foreigner), comparing bamboo baskets, getting their assignments, filling their water bottles. Kishimoto Koichi, a retired software engineer who knew not a single plant when he first volunteered a decade ago, was their leader. In certain seasons, they cut trees. In others, they found and marked out rare or important plants. At almost all times, they cut back the persistent sasa, a small but very vigorous and fast-spreading bamboo, along with other weeds. Zasso is the name for weeds in Japanese. It is wonderfully onomatopoeic.

The others had gone out to work before we were ready to follow. We walked on an asphalt-paved park path. Suddenly, Kishimoto made a left turn between two newly planted sweet potato plots. “We planted these,” he said in passing. He was walking straight into a wall of bamboo overhung by large old once-coppiced oaks. He pushed his way into the thicket. “Come on,” he told me. Just inside, there was a clean dirt trail, completely invisible from the path. There was a small sign saying that this area—about 4 of the park’s 40 acres—was reserved for the volunteers. He smiled as I came up behind. “Our secret garden,” he said.

Their restoration went up and down hill, in sun and in shadow. They aim to bring back both konara and kunugi coppice, with all the plants of the booga mori. When they started in the 1990s, they simply tried to cut back all the bamboo and coppice all the oaks. It was a disaster. The sasa came back faster than the trees, and they were unprepared to keep after it. They made several false starts before they learned how to manage a regenerating coppice wood. (It heartened me to hear it. They were just like we were at the Met, with no manuals and no information online.) Now, they used a carefully plotted set of thirty-seven field boundaries. Some are designated for active work, others to make a buffer between managed and unmanaged woods. It was an oak and bamboo ballet, measured in a tempo of years. Each year, they cut one of fifteen areas, bringing back its trees. In a decade and a half, they return to the same area. Meantime, the volunteers visit all the actively managed areas at least once per year, keeping back the bamboo and the other invasives.

There were strange tiny flexible arcs in blue or white plastic that marked off certain patches of ground. These protected where the volunteers had found rare or coppice wood species. More than sixty different species had returned since they began, almost all from the dormant seed pool in the overgrown woods. (Animals had also returned. A newt thought to be extinct in Metropolitan Tokyo was recently found in a stream here.) Kishimoto showed me a tall multistem shrub that they have brought back and nurtured. It was a honeysuckle called Uguisu kagura that flowers dark pink in early spring, just when the bird called the uguisu begins to sing, and develops bright red ovoid fruit in summer. The bird loves to sit on its stems and swing while it sings, so the common name for the plant means, “where the uguisu does its sacred dance.” As if responding to a cue, a bird started piping in the trees around us, dodleeeedo, dodeleeedoo. Do deedoo deedoo. The call would follow us for the next half hour, sometimes making it hard to understand one another. It was the uguisu, just at the end of its season of song.

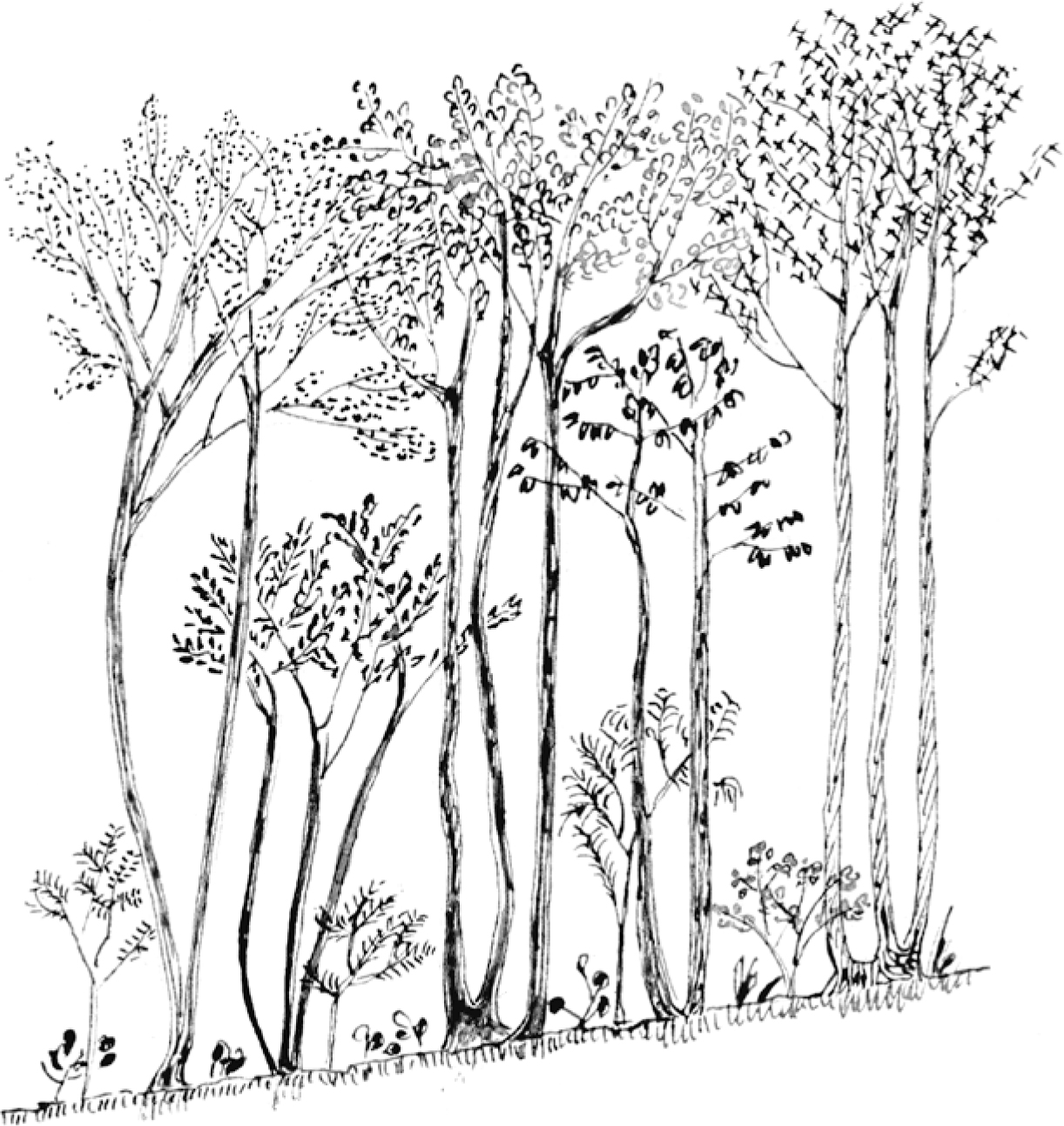

A selection of resprouting konara and kunugi oaks, at Sakuragaoka Park near Tama New Town, Japan.

The volunteers were in a shady hollow, armed with shears, small saws, hedge trimmers, and a lot of bottled water. It was a muggy morning. Their talk was much quieter here. The work was not glamorous. Mainly, it was weeding what was invasive and precisely not weeding what was meant to remain. But it was work done together, and they obviously enjoyed the company of their fellow weeders. When they looked to the edge of the area, where a buffer section was, they saw how much difference their work made. Even in the buffer, the bamboo was as thick as the stuffing in a pillow. For two hours in the morning and another three in the afternoon, they would keep it up. The oaks here had been cut five years ago, and they were now back to twelve feet tall, each stem as big around as a person’s arm. A rectangle of white arcs surrounded a stand of a low plant that looked like Solomon’s seal and was clearly in the same genus. “Miyama narukoyuri,” Kishimoto said. “A lily that has come back.”

The Sakuragaoka Park Volunteers have restored no great area here. Most of the park was beyond their reach, both logistically and contractually, but they have restored the connection of hundreds of people to their own land and their own past. Every year, they have festivals. One in July celebrates the huge golden spider lily that has returned to sunnier spots of the coppice woods. The volunteers give guided tours to find it. In autumn, they hold an acorn festival, at which they plant new kunugi and konara. In February, there is a rice festival, at which they make mochi cakes. They compost rice bran, nuka, to fertilize their sweet potato fields, and they learn to make nukazuke, pickles in fermented rice bran. “We used to get more volunteers than we do now,” said Kishimoto, ruefully, but that is not because the idea is dying out. It is because there are now more than two thousand such groups in the Tokyo area alone.

Not far away, on the border between Metropolitan Tokyo and Saitama prefecture, are two of Tokyo’s principal reservoirs: Tama and Sayama. Urban sprawl rapidly overran the Sayama Hills here, just as it had in Tama. An aerial photograph shows a wave of silver, gray, and white, the buildings and roads, their light colors washing up against little fingers of green forests that hug the shore of the reservoir and the courses of streams. This was the place where the director Hayao Miyazaki had set My Neighbor Totoro. Here in 2017 Totoro was not leading protests, but preserving satoyama.

The Totoro no Furusato Foundation (Totoro’s Hometown Foundation) was founded on the model of the United Kingdom’s National Trust. Funded in part by Miyazaki himself, it aims to prevent development of what remains of the rice fields and the booga mori in the Sayama Hills and to restore degraded ones. In response to the protests over vast projects like Tama New Town, the Japanese government made it much more difficult for large developers to acquire and develop whole swathes of countryside. On the other hand, they put no restrictions at all on small developers. The result was a piecemeal destruction of the remaining satoyama niches. In particular, developers from elsewhere in the Tokyo region bought small parcels as dumps for contaminated soils and construction debris. Especially valuable were hill-bottom wetland areas, where the dumping was easy.

The Totoro Foundation started to outbid them, and when the developers could not be outbid, the owners have often been persuaded to sell the land for preservation rather than to have it buried in garbage. Sometimes, the foundation bought degraded land, as well, and restored it. As of 2017, there were forty-one Totoro no Mori (Totoro Forests) in the Sayama Hills. They amount to only about twenty acres in total, but those parcels have cost the foundation more than $5 million. In some places, they simply preserved coppice woods, without putting them back into cycle. In others, they begin the cutting anew, and plant new oak when needed. Some remove the fill from ruined paddies and restore them as working rice fields. We walked with Tsushima Ryoichi and Andoh Naoko of the foundation beside a restored paddy about to be planted. There were houses on one side, palm trees escaping from their gardens and chestnut groves on the other, but the frogs were setting up a terrific din. “The frogs are thanking us!” said Andoh. “They said, ‘Don’t invade here! Give us back our paddy pond.’ And we did.” The goshawks on the overhanging branches must also thank them, for providing abundant frogs, as must the fireflies that have returned and the tanuki. Here at least was one refuge for the displaced raccoon dogs.

Volunteers were important to the success of these efforts. So were local governments. While we were looking at one forest, Tsushima, the foundation’s executive director, met a random visitor and signed him up to help. To restore a paddy, it was necessary not only to remove fill soil but also to turn the original soil and pull the aggressive weeds—not once, but three times per year, until the paddy ecosystem is reestablished. “It takes a lot of biomass energy to restore a field,” joked Tsushima, watching his young recruit walk off. The foundation was not allowed to buy farmland, so sometimes the city or prefecture bought the land and gave it to Totoro to manage. Local governments also bought up forests adjacent to Totoro Forests, extending the preserved areas. Private citizens’ groups also helped. One owner of a small golf driving range organized his neighbors to resist development and begin preservation. “He is the reason there are Totoro Forests in this place,” said Tsushima.

A test came when Waseda University decided to build a satellite campus in the Sayama Hills. The original plans cut hilltops and filled paddy lowlands to make the campus. Totoro objected. So did the local governments. So did the local citizens. Instead of fighting, the university joined them. They resited the buildings and preserved the wetlands. Waseda became responsible for the annual management plan to maintain the restored paddies, reed lands, and grasslands, and the university contributes money each year to the maintenance. At first, the foundation thought it would make paddies, then leave them fallow for a decade to save money, but where sixty or more species had come back from the buried seed bank when they established the paddies, most of them went away again when cultivation stopped. The diversity depends upon the activity of the people.

Beside one field of six-foot-tall susu grass, the university faced a new laboratory building away from the wetland and screened all the windows on that side. The idea was to keep night lights from disturbing the rhythms of the creatures who live there. “Now the researchers complain it is too dark,” said Tsushima. He smiled just a little, then caught himself. There were persistent birdcalls and answers as we bushwacked through the susu, the grass that once was used for thatching and for fodder. It was the first of the hototogisu and the last of uguisu together. The former was a kind of cuckoo who, like western cuckoos, had a penchant for laying eggs in other birds’ nests. In this case, the uguisu was most often the recipient of the hototogisu’s eggs. Both birds were common in the woods and grasslands.

Recently, their work has also brought back the kayanezumi, the harvest mouse. It is a tiny native mouse. The scientists who named it wanted us to be sure about that: Micromys minutus is its Latin name, which, loosely interpreted, means “Tiny mouse. I mean really really tiny.” It is small enough that it actually nests on the grass stalks themselves. These mice build the small ball of their nests out of the grass itself, high on the stems. The nest starts out green and turns brown.

At the shrine in Kyoto were the protector mice. In the Totoro Forest, the mice were protected. There was not just human largesse here, but a kind or reciprocity. The iconography of the Shinto prayer card—you bought it at the shrine and hung it there with your prayers—was almost exactly the same as a natural history drawing of Micromys minutus. In both, one mouse stood tall, the other stooped, enfolding. Coincidence? I think not. Rather I think that in some places there has remained a common understanding that all creatures share these two modes of being, in science, in song, and in prayer. One challenges the enemy directly, the other surrounds evil and causes it to surrender.

Near the big cities, it is a struggle just to keep back the buildings and the dumps. In the countryside, most coppice oak woods have been cleared and replaced with plantations of Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica), pine, and hiba cedar (called ate). Where they have not been cleared, they have simply been abandoned. But on the Noto Peninsula, on the western coast of Honshu, there is a move not only to restore but also to reuse the hahaso.

Ohno Choichiro inherited a charcoal business started by his father in woodland near the town of Suzu on Japan’s far western Noto Peninsula. The area did not escape the postwar mania for profitable plantation forestry. A lot of it was indeed planted with the then fashionable red pine. But the soils were too good. The pine didn’t like them. When a major pest appeared, the pines went down, and the oaks came back.

Ohno called his business Hahaso. It was modest: He had three employees, three trucks, a splitter, chain saws, a mowing machine, and two charcoal kilns. These last stood in a wood-framed hut with corrugated plastic walls and a corrugated iron roof. When you walked in, you seemed to have entered an amateur exhibit about Eskimos. There were twin igloos fashioned out of concrete. Ohno invited me to go inside one of them. “In you go,” he chuckled. “Just like the wood!” It was a tight fit. Inside, three or four hundred upright sticks of finished charcoal, each about three feet tall, leaned against the back wall. They were cooling. It took about a week to cook the charcoal, and another week for the batch to cool.

Some of the charcoal went to city barbecues, where it was in demand. Sacks full of cooled and cut charcoal—made from twenty- to thirty-year-old coppice—stood in ranks in the shed, almost ready for sale. Ohno made the best money on charcoal for the tea ceremony. For this purpose, he used only kunugi, which burned hotter, and he cut it young, when the stems were only about ten years old. He chose the straightest stems. When they were cooked, cooled, and cut into six-inch lengths, each was a thing of beauty: obsidian black all over, inside and out, but look from the end of the stem and you saw a perfect pattern of growth rings punctuated by the sunburst pattern of rays cells, each of which runs from the pith out to the bark. Every year, Ohno cut about four square kilometers of woodland and made about twenty thousand tons of charcoal.

We went to see fresh-cut coppice beside a dirt road. The other side of the road was lined with rice paddies. Until recently, the wood had belonged to a ninety-year-old man who cut it in cycle to get firewood and logs for growing shiitake mushrooms. When he died, his children had had no use for either, so they asked Ohno, their neighbor, to manage the woodland. This was its first coppice since the old man had died. There was nothing picturesque about it, from a distance. It looked like a clear-cut bit of hill. with leftover stumps, some brushwood scattered here and there, and a tremendous amount of grass and weeds.

Only when you came close did the beauty begin to emerge. Nine-tenths of the stumps were sprouting back. There were fresh herbaceous greens tinged with the red of new leaves and purply twigs just beginning to turn woody. Here were konara and a little cherry, both coppiced alike. Ohno pointed out taranome and katakuri growing up in the opened land. One will make tempura, the other its batter. He looked over his work. “This now will wait twenty years,” he said. “Then I will cut it again. If I am lucky, I may get to cut it twice in my lifetime.”

In a nearby woodland of fifteen-year-old trees, I had the feeling I was swimming in a seaweed forest, just as in the pollard grove in Golden Gate Park. Five or six wrist-thick trunks rose from each stump, like bull kelp from its holdfast. Uphill and down, the clumps of stems rose and waved. The canopy was closed here, but it still felt open. Sun reflected in off the light-colored leaves. The sasayuri, an endangered lily, and rhododendrons have now occupied the understory. This was Ohno’s family’s land. His father had first cut it forty-five years ago. Three decades later, he had trained his son there. “He sent me into the hardest places,” recalled Ohno with a laugh.

To manage a booga mori requires successive generations. Ohno was not sure who would follow him, but he has not slowed down. He enlisted the internet, which may provide him with a new generation. He recently bought land on another slope nearby. There, he has already begun to plant kunugi, hoping to expand his tea ceremony business. The new land had been in mulberry and chestnut, but it had gone wild for at least a decade. He used volunteers to help clear it and prepare the soil. “It was really hard work!” lamented a young forester, Ifumi Yuho, who had been among them. For the new section, therefore, Ohno decided to hire professionals to prepare the soil. In two weeks, he raised $18,000 on a crowd-funding website. The work was about to begin.

It was such a small enterprise, compared to the vast conifer plantations that now occupy much of the land that was once in hahaso, but it was a beginning. Above the twin kilns in his corrugated shack was a kamidana, a Shinto home altar. It presided over the space with a rope that marked the presence of the kami. Standing on the altar were tiny facsimiles of two trees, konara and kunugi. “Here he works with fire,” said Ifumi. “It is dangerous and sacred, so he calls on the kami to bless the work.”