Say it, no ideas but in things—

nothing but the blank faces of the houses

and cylindrical trees

bent, forked by preconception and accident—

split, furrowed, creased, mottled, stained—

secret—into the body of the light!

—William Carlos Williams, Paterson, Book 1

Just as Walt Whitman in his poem “This Compost” foresaw Selman Waksman’s cure for tuberculosis, so William Carlos Williams in the first book of Paterson (1946) foresaw what Francis Hallé, Roelof Oldeman, and P. B. Tomlinson would make plain in Tropical Trees and Forests three decades later (see page 42). By model and reiteration—by patterns of branching—every woody plant rises into the body of the light.

It is not only plants. The whole world is pregnant with branching.

In every place.

At every size.

If every branch is alive, then nothing in the whole world is dead.

Under the electron microscope, the sheets of montmorillonite clay are seen to stretch, bend, divide, extend. To join again and to divide again. When you pick the bark off an infected oak, the black whips of the rhizomorphs of the fungus armillaria run in parallel lines, only to branch in every direction. The mycelia of the fungus are running through the oak’s cells in the same way. When they come to a wall, they digest and breach it, then divide entering the next cell, and so on until the plant stops them. The branches of the mycorrhizal fungi, without which few trees could live, ramify within the cells of the roots and into the surrounding dirt, helping the plant absorb water and phosphorus. All the rivers of the earth are questing downhill, meeting resistance, worming their way through, breaking into new streams and flowing onward. In the flats come the meanders, where the stream braids, its separate channels meeting, then dividing again. Henry David Thoreau was delighted with the intestinal branching that the water made as it flowed down new railroad banks, freezing and thawing on the way.

As water percolates into the dirt, it creates an interlocking system of channels through which it flows to the water table. This makes soil structure. There is no more penetrating and persistent force in the world than the one that shows itself in branching. Even underground, the dirt is a network of stems made by percolating water, which finds the pathways among the aggregates of mineral and organic matter. “Water is the strongest thing on Earth,” wrote the Taoists, “because it is not afraid to go to the lowest place.” It breaks rock, carries down iron into the depths, changes crystals of silica and aluminum into the arabesques of clays, distributes organic matter, frees and spreads the elements that plants need to grow.

The roots of all plants inhabit this network, mirroring the branch work through which the water flows. As the roots take up the water from these passageways, they pass it upward to the crown of the plant. The branches above ground are an answer to the ones beneath it. Pollards, with their repeatedly trimmed and resprouting branches, I have observed, often occasion finer fibrous branching in the roots. What is above responds to what is below.

What a wonderful word is anastomosis. You can hear it happening as you say the word: ah-nass-tow-mow-sis. It is the way in which branches that have separated, rejoin, then repart. Ahnass . . . we part; towmow . . . rejoin, sis . . . we part again. The rivers of airways in the lungs through which the blood flows to harvest oxygen anastomose. The meandering slows the blood enough to fill it with oxygen. In your guts the same principle slows the passage of digested food so that its goodness can be harvested for the body’s use. Veins and arteries anastomose. Every leaf of every plant is a network of anastomosed veins that distribute water to the chloroplasts, as well as distribute the products of photosynthesis. Slime molds anastomose. So do highways.

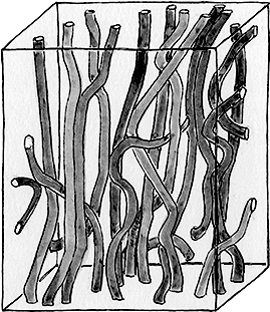

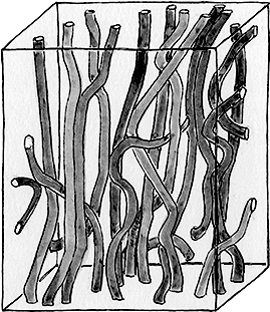

A network of vessels, the xylem, ascends each tree. Its long, winding, interconnected cells stretch from roots through trunk and branch to the slimmest newest twig, bringing water and nutrients from the dirt to the leaves. It constantly anastomoses as the tree grows. The interlacing vessels not only slow the flow, they also make a wildwood of forking paths, so that if one channel is blocked, another can find the way. This happens inside every tree, and is the reason that they can live five hundred years, in spite of every effort of pathogenic, pestiferous, or storm-falling things to destroy them. How many such vessels are there in a mature tree? A ring porous tree like a red oak has fewer and larger vessels than does a diffuse porous tree like a sugar maple, which has more and smaller vessels. The former might on average have around 213 million vessels, the latter about 1.3 billion. In each tree. And every year, the new wood makes more of them.

The birth and persistence of the xylem shows that branching is one of the generative ideas by which the world goes on. Without the idea, how could it ever come to pass that millions of cells each year are formed, seek neighbor cells of the same kind, join each to each in a vast anastomotic network that ascends the tree from base to crown. Then, to add acclamation to calamity, the whole daisy chain of interconnected cells must die and empty out its contents, leaving just the cell walls. Only then can it begin to do what it was born for: to carry the water and nutrients all the way from the roots into the veins of the leaves. There, either the water evaporates, empowering more water to keep rising from the ground, or it enters the green cells where it is half the material of photosynthesis. If one path is blocked—by a fungus or a chain saw, it doesn’t matter—another way up remains.

All these wanderings ask a question, and wood is the answer. What has fallen from the sky and percolated into the dirt, rises up against gravity through the river paths in every stem. A tree’s array of sprouts, twigs, and branches, continually produced anew, is both the means and the memorial of this central idea in things, through which the world around us is created and maintained.

A sample of the xylem vessels in a square centimeter of wood. Wherever they meet, they connect, making a labyrinth of channels.