Half the first season was gone, and I still had nobody to advise me on pruning my pollards. They looked pretty good. People were sitting by the hundreds in the trees’ aborning shade, but how would I get them to grow in beauty like my favorite pollard pinups? A friend of mine suggested Neville Fay. He specialized in such things. I sent him an email. Yes, he responded, he would be happy to ride around with me near his home in Bristol, England, looking at old pollards. We would visit the Somerset Levels, the nearby coastal bottomland, a place only borrowed from the water. In early February of 2014, it looked like the water was about to foreclose. More than 17,000 acres of the Levels had been flooded. A whole village had been abandoned, and another cut off from the rest of the country by the rising. Not anything like as bad as the flood in 1607—possibly a tsunami—which had killed two thousand people and inundated the whole lowland, where the average height above sea level is only eleven feet. But bad enough.

We went for a drive. The ribbon of tarmac was ebony black and polished, since the water had receded only the day before. We were inserted in thick fog like specimens kept from breaking in a bed of cotton wool. For a time, we were the only specimens in the place. There were ditches full of black water, beaten-down brown grass, and a green scruff of wild garlic on the road and channel verges.

That was when the apparitions started. One by one and then in lines, they began to appear resting on the cushion of fog. The first was an ash tree, set just behind the beginning of a gray winter hedge that punched a hole in the fog into which it quickly disappeared again. The ash had a trunk like a torso that rose only about 10 feet into the air, but was about eight times as broad as a man’s waist. From there about a dozen branches snaked off in every direction like Medusa’s hair, only sparser and each strand thicker. Every stem was maybe 8 to 12 inches in diameter, and each stretched anywhere from 12 to 25 feet from the bole—that is, from the spot where the tree had first been pollarded, the top of the torso. Some stems arose alone, while others intertwined. A little farther along the hedge another ash appeared, this one with a shock of many branches, some rising from the bole and others from lower on the trunk, making a symmetrical fan of branches. Another punch through the fog and a third ash stood beside a gunmetal-gray steel farm gate, its torso the same height and girth as the others but its branches lopped crew cut–style. From these three alone, it was immediately clear that J. R. R. Tolkien had not invented the Ents, his tree people in The Lord of the Rings. He had seen them.

The hedge kept on, but the ashes disappeared. The fog settled lower, if that was possible, until it seemed to skim along the road like blown smoke. Then on the opposite side, a ditch of dark reflective water appeared, turning to parallel the track. Beside the ditch on the road side began to appear willow trees with boles only about five feet tall and dozens of gnarly branches rising at a steep angle from each, as though the willows were meant to be broomsticks for the much bigger ash trees. Then the fog closed in again. Next, half a dozen willows appeared, each cut with a trunk about the same height as the last, but this time the branches were younger, suppler, fresher, and more numerous, like a collection of buggy whips. One bole had a broad column of decay that spilled little blocks of pale wood onto the ground. The fog closed up on these specimens. The next appeared suddenly. They were blank boles, monster heads that arched over the water, with bright circles the color of wheat all over their heads, where the branches had been cut, perhaps only a few hours or a day ago. Arborists call these blond rings “cookies” and admire them when they are well made: at the branch collars and without rips or scorings into the remaining stem. Someone was still pollarding these willows, a hundred centuries after the first willows had been cut on this ground.

The head of a recently pollarded willow on the Somerset Levels.

That someone was not far to seek. On the opposite bank appeared a farmstead with the gray ashlar block of a barn half covered in ivy and finished on the end with modern red-gold hollow bricks. A fence enclosed the farmyard: it was made entirely of slender woven willow withies. Thicker willow sticks bent into upright spindles were the warp on which the slender withies twined. There are companies still in business on the Levels that make and sell fences, hurdles, baskets, and brooms of pollarded and coppiced willow.

Young pollard sprouts on willows near the main house and barn.

Along the far bank of the ditch grew a long line of willows. Each had a straight clean trunk five or six feet tall, and each was topped with a like array of straight slender stems, arching up and out like the strands of an old-fashioned shaving brush. They reflected perfectly in the still water before them. Rectilinear regularity and wild exuberance here met and embraced. They were as beautiful as any ornamental pollards I had ever seen. Fay assured me that they were made for use, not strictly beauty, but we could clearly see the impulse in the maker’s hand. Near their house, they wanted the useful to be beautiful too.

Here was help for my perplexities. It was clear from all these willows of different sizes and styles that the pruners had trusted the trees and had listened to them. They cut with vigor, then responded according to what the trees gave back. Where they wanted thicker poles, they might thin the tops, and they might also remove some one year, some the next, choosing each size according to their use for it. When they wanted thinner poles, they might let all the sprouts remain, removing only unhealthy ones, and so let the stems get longer while still slim and unbranching. In many of the pollards I had seen in California, the pruners had seemed to want to create the finished shape from the first cut. In fact, I saw on the Levels, you could rather cut deeply, using timing and selection to get the stems you wanted. The result was a joint creation, the work of companions.

I found that I was learning much more than I had bargained on. I had wanted a book of instructions, but I began to glimpse a history that stretched back almost farther than I could imagine. This foggy flooded outpost of the sea opened for me a deep past where pollarded and coppiced trees were not an ornamental choice but a living need. These useful pollarded willows were by no means the first of their kind. Forty, fifty, sixty, seventy, ninety centuries back, it began, not only here, but around the world, wherever there were sprouting trees. In the Somerset Levels, however, a weaving of raised bogs, blanket bogs, reed swamps, marshes, and winding rivulets had given way today to 250 square miles of peat in which the perishable work of so many centuries had been preserved. This was a very good thing for me, because I now wanted to discover how these trees had been cut in the ancient past.

Where a dry land archaeologist finds only the postholes into which stakes had once been placed or at best traces of poles or boards in dried mud, the bog explorer finds the things themselves, cast in wet peat. Archaeologists called the ancient world the Stone Age, but that is because the rocks were all that had survived, rather than because they had been the primary products of those cultures. The Levels showed that that time might better have been called the Wood Age. In fact, archaeological work in Somerset had begun when people mining peat for fuel came upon inconvenient posts, planks, stakes, floors, fences, hurdles, roof thatch, clothing of flax and lime, lime rope, ladles, axe handles, cat and human figurines, toy wooden axes, coat racks. . . .

In 1975, men from the Eclipse Peat Works had been digging merrily along with a big loader. (Not many years before, the firm had created a small railway with moveable tracks that they shifted around the Levels, on-loading and off-loading the peat turves, which they then piled in storage in stacks larger than Westminster Hall.) They had come upon what seemed like a fallen fence of woven wood. “Better call the archaeologists,” they had reasoned, referring to the Somerset Levels Project, which had been going on for a couple of years then. The peat guys knew the drill, but they didn’t know what they had stumbled onto this time, though it sure looked like a farmstead fence.

The archaeologists recognized it right away, although they had never seen such a fine one. It certainly looked like a long fence made of panels, each about ten feet long and four feet wide, but it had never been stood on end or pounded into the ground. Within weeks, they had made another similar find nearby. These finds were not fences but trackways, ancient bridges. Both had stretched across the fen between Meare Island and the upland Polden Hills. They had brought neighbors and their sheep across the wet levels to each other’s settlements.

Both had been made entirely of coppiced wood, harvested in the uplands, fabricated by skilled stem weavers, and brought to the bog. Some of the panels had simply been laid on the marsh surface, but most had been secured with stakes driven on either side of each panel. They had been woven with such care and skill that not only human or sledge traffic, but even the slender hooves of the sheep could pass without sinking. With care, two could pass abreast. Experiments showed that without these trackways a human foot would have squelched five or six inches deep with every step.

Since then, hundreds of tracks or parts of them have been discovered in the peat all over lowland Europe, more than thirty in the Levels alone. Some were made of whole slender trunks, some of hurdles—woven poles—and some of planks, but most were made from coppiced trees. During the Neolithic, and into the Bronze and Iron Ages, these handmade walkways were as common as sidewalks in a city.

A traditional Scottish game shows how life goes if you live on a trackless fen. It is called the bog race. Leave it to the Scots to create a sport that resembles torture and in which it is not a question of in what order you finish, but of whether you finish at all. In fact, a Bronze Age person has been found facedown in a bog, tacked under a hurdle, so perhaps the original bog race had been a form of capital punishment.

I participated in such a race set up at 10,000 feet, near a stream meander on Golden Trout Creek in the Sierra Nevada of California by my teacher, a Scot named Peter Reid. It was a simple course: somehow or other, the race committee managed to place a standing stake far out in a bog. The poor contestants had to make their way by foot and flounder from the bog edge, out to the stake and back again. As I found to my cost, not many do.

You sank only half a foot when you started, so you reasoned, Okay, this is going to be a slog but doable. Soon, you were up to your shins, then your knees. Quicksand nightmares ensued. Obviously, the best course was to make yourself flat and wide, but it was a task to lie down at all, when you had to laboriously extract both legs from depths where they seemed to have been set in concrete casts. You flopped forward, then back. Finally, you managed to stretch out over the surface, sinking only a few inches and smelling the anaerobic undersides of the disturbed bog. The race then became a swim across the scratchy surface, doing a flailing imitation of the breaststroke, remembering what it was like as a baby or a reptile to slither. Suddenly, you ran into a deep patch and you were really swimming, only to heave up against the semisolid surface once more. By halfway to the stake I was worn out. Only two people finished the race that day. The winners.

It took planning and skill to make a trackway, though the very first trackways may indeed not have been made by man at all, but by beavers. There is evidence that in the Mesolithic, people not only crossed marshes on beaver dams but sometimes made away with the beaver-cut wood for their own use. A 9,000-year-old man-made lakeside platform found in Yorkshire contains both wood cut and split by human beings and poles stolen from the beavers. The earliest trackway may simply have been piles of brushwood or lines of logs. To make woven hurdles took imagination and craft.

On the Somerset Levels at Walton Heath, the intact hurdles were remarkably similar. Each pole had come from trees—mainly hazel—coppiced and assembled at the same time. There had been a workshop on the Levels. Perhaps there had been a weaving season: the men wove hurdles, the women flax and wool. In the Neolithic, weaving was not a menial task, but a prestigious art. The most skillful and reliable practiced it. It was the way to humanize what Great Nature gave.

One intact hurdle of the Walton Track was about ten feet long by four feet wide. It consisted of six transverse warp rods, each of hazel around an inch in diameter. Woven over and under all of them was a weft of 64 long slim hazel rods, each about half to three quarters of an inch thick. The work was perfect: 32 rods over, 32 rods under each of the warp transverses and fitted so tight that the mud could not squelch through them. Were it a coat, you could have slipped it on and worn it. The hurdle had been stabilized by split willow withies, soaked in water and knotted or spliced to keep warp and weft together. On several of the hurdles, the knot could still be seen: a square knot, left over right, right over left, tied 44 centuries ago. John Coles, the archaeologist who led the Levels Project, estimated that a maker and his assistant could fashion about ten panels per day. The Walton Heath Track required about forty panels, because some were stacked on top of others to get across the deeper spots. It took about four days to make the hurdles, then a few days more to lay them.

At about the same time and using hazel and birch from exactly the same source, a different team made the panels for an eighty-meter track across the nearby Ashcott Heath. These panels were not quite as tightly woven as those nearby, but the maker had had a brilliant idea for the ties. Instead of using easily broken withies, he selected stems that had whippy slender ends. He bent and tied these stems back and over the other rods to stabilize the structure.

All the wood for both tracks was cut at one time, and woven green, while it was still pliable. There are more than 14,000 rods in these two tracks alone, a small fraction of the dozens of tracks that once crisscrossed the Levels. Where did they get the wood? Every bit of it had been coppiced. The understories of the open oak woodlands of the Polden Hills were carpeted with multistem hazel. Cutting each of these back to its base on rotations of from four to ten years, the craftsmen got several dozen stems to grow straight off each of the cut stools. The new stems typically grow straight and true, without lateral branching for at least the first six years. And even after ten years, the diameter of the wood at its upper end was only a little less than at the lower end. It was a natural factory of poles.

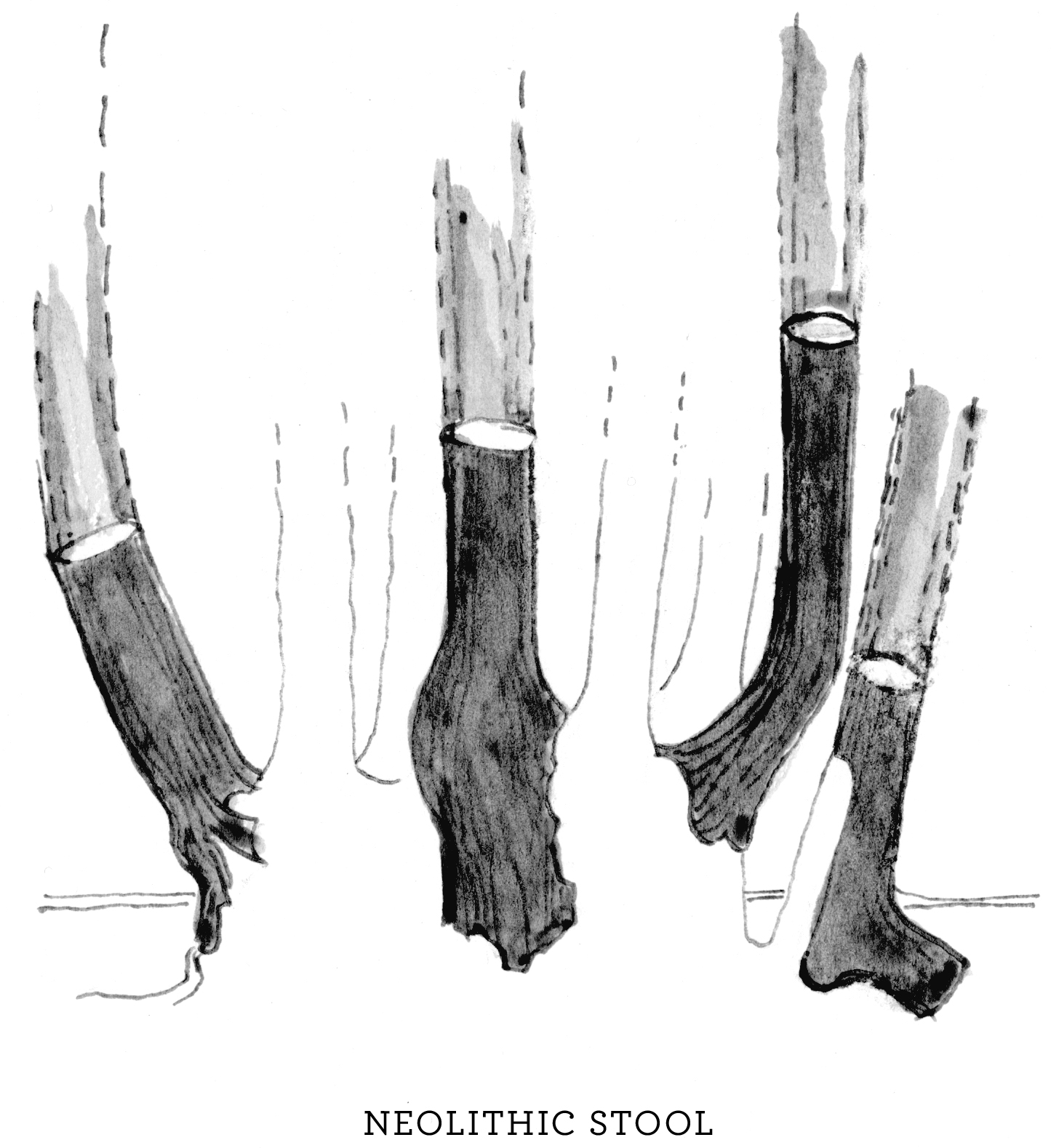

The Neolithic axe harvested this crop. So as not to damage the perennial stool—the stump to which all the roots were attached—the woodsman harvested the rods by pulling them back from the stool, peeling them back to expose the ingrown heel of bark (see illustration, page 76). He would then cut outward with his axe, severing the rod without scoring the stool. This left a long slender tongue of wood. He could then lay the sliced end against a hunk of down wood and crosscut the base, removing the tongue. The archaeologists studying the tracks diagnose coppice not only from the long straight poles without lateral branches but also because of the scalloped butts where the stem was joined to the stool and sometimes by the butt end itself, which contained both the current generation pole and a bit of wood left from the previous cutting. All of the rods showed a very wide first ring of growth, characteristic of the necessarily vigorous sprout that arises from the new-cut stool.

The base of coppiced hazel rods from trackways on the Somerset Levels, showing the likely shape of the stool from which they were cut.

There were uses for the coppice besides. The system also made food and pottery. They would sometimes top the stems in summer, harvesting the leafy branches for livestock feed. And the same coppice stems that might be needed one year to make or mend a trackway might go the next year to make charcoal for the pottery kiln.

To our ancestors, fens and bogs were better than Scarsdale, San Rafael, or Brooklyn Heights as a place to live. They had all the materials for making, all the food to eat, and easy access to medicine, but without the tracks they were no easier to use than a suburb with no road to reach it, or a fine apartment in Brooklyn Heights from which you had to swim to work each day. In many ways, it was more difficult, because the water rose and fell on the Levels, not only with the storms but also with the not infrequent changes in climate pattern. When your road is a track laid on the surface, a rise in water can (and sometimes did) float it away.

Coppicing was not new to these fen dwellers of the 45th century BP. More than a millennium earlier, in the 59th century, at the dawn of the Neolithic in England, they had built the great Sweet Track, a bridge to link Meare Island to the glacial sandbar called Shapwick Burtle and then on to the Polden Hills. This track was not a few hundred feet but more than a mile long. In my book Oak: The Frame of Civilization, I have considered how oak planks split with wooden wedges out of whole logs made the surface of the Sweet Track, but the underlying coppice was what made it work. The Star Carr platform, which was discovered on a lake bank in Yorkshire, shows that almost 10,000 years ago Mesolithic people could split out clapboard, but it was apparently not until the Neolithic that they could reliably cut thousands of stems so they would sprout again.

To build the track, the makers of the Sweet Track coppiced hazel, ash, and oak on a ten- to twelve-year rotation. This gave them bigger poles to work with. First they stretched out long coppiced poles end to end to mark the track across the reed marsh. For the deepest section, they laid double poles, one atop the other. They then took stout poles by the dozen, cut them to size, and sharpened each of them at one end. They drove the sharp-ended poles in pairs into the marsh bottom, making an X that crisscrossed right on top of the long pole line. Every three feet or so along the length of the track, they made the same X. When they laid the notched oak planks onto the X-laid supports, the whole structure was supported three ways: the underlying poles kept it from sinking and the Xs from drifting apart; the Xs stabilized the boards along the trackway lines; and the boards prevented the Xs from warping or lying down. Just to make double sure, the makers cut holes in some of the oaks planks and drove slender pointed coppice stems through the planks to reinforce the connection to the marsh bottom.

Many of the new balletic bridges—in New York, Boston, Barcelona, and elsewhere—use much stronger materials and support much heavier weights, but they are based upon exactly the same X principle that was long ago enunciated in the Sweet Track. A crisscrossed structure atop a stabilizing base made it possible to run a long passageway over water.

We have not gone too far beyond our ancestors in intelligence, but we have forgotten one thing that they deeply knew: the instinct of thanksgiving. All along the edges of the Sweet Track and along other tracks, archaeologists have found sacrifices thrown into the marsh. One type consisted of pots full of hazelnuts. A toy wooden axe was also found beside the Sweet Track, but more impressive, a lovely green jadeite axe head—not a toy at all but a fine real axe imported all the way from what are now the French Alps. This axe head had never been hafted and never been used. It was offered in thanksgiving.