THE SIEGE OF VICKSBURG

WARREN COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI

MAY 18–JULY 4, 1863

COMMANDERS

|

Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant |

Confederate Lieut. Gen. John C. Pemberton |

PARTICIPANTS

|

35,000 (initial force) 75,278 (after reinforcements of June 14) (Army of the Tennessee) |

30,581 (Pemberton, Army of Mississippi) 26,000 (Johnston, Department of the West, rescue army not engaged) |

CASUALTIES

|

Union 763 killed 3,746 wounded 162 POWs/MIA |

Confederate 3,202 killed or wounded 29,495 POWs |

VICTORY: UNION

OVERVIEW

The capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in the western theater allowed the Union to gain control of the Mississippi River. A vital transportation route extremely important to both North and South, it was also an important part of Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan for suffocating the South with the blockade. Controlling the Mississippi effectively cut the South in half, separating the eastern portion from the three states that provided many of its supplies (Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas).

Early in 1863 Grant established a base of operations on the Mississippi at Mulliken’s Bend, roughly ten miles northwest of heavily fortified Vicksburg. He spent a couple of futile months trying to open waterways for Admiral Porter’s boats and ironclads. Giving up, Porter finally ran the gauntlet of Vicksburg’s batteries, then ferried Grant’s troops across the Mississippi at Bruinsburg, about fifteen miles southwest of Vicksburg. Grant then had to get between the two Confederate armies of Lieutenant-General John Pemberton and General Joseph Johnston to prevent them from uniting against him. He chased Pemberton into Vicksburg and then laid siege to the city.

Grant attempted to break through the city’s defenses with two assaults, but both failed. He decided to starve Pemberton’s army into surrender. He also tried to wear the Confederates out by bombarding the city. While he didn’t have any siege guns, Admiral Porter did lend him some of the large naval guns. With Grant to the east and Porter’s boats on the Mississippi to the west, the city was pounded by shot and shell.

“The mortar boats,” wrote Porter, “were kept at work for forty days, night and day, throwing shells into every part of Vicksburg and its works, some of them even reaching the trenches in the rear of the city.” In his dispatch on the day Vicksburg surrendered, Porter noted, “The mortars have fired seven thousand mortar-shells, and the gunboats four thousand five hundred. Four thousand five hundred shots have been fired from naval guns on shore, and we have supplied over six thousand to the different army corps.”

In addition, Grant’s army had its own field artillery firing into the city.

After a month and a half, conditions in Vicksburg were wretched. People resorted to eating mules, dogs, and their own shoe leather. About half of Pemberton’s men had incapacitating scurvy, dysentery, and other diseases, putting him under great pressure to surrender.

Johnston’s army was too small and ill-equipped to take on Grant, especially after Grant received reinforcements greater than Johnston’s entire force. Johnston had about 26,000 men to take on Grant’s 75,000. Still, he was preparing to attack, but the siege ended before he was ready.

Pemberton surrendered on July 4, thinking that Grant would give him better terms on the holiday. The surrender, coming as it did at the same time as the Union victory at Gettysburg, tremendously boosted the North’s morale, landing a huge blow to the South. With the fall of Vicksburg, the Confederates’ final foothold on the Mississippi—Port Hudson—surrendered without a fight, giving up an additional 6,000 prisoners.

Grant suddenly achieved international fame—but events could have easily gone another way. When Grant first described his plans to Sherman, the latter strongly opposed them because they violated one of the basic principles of war: Maintain and protect your supply line. Grant proposed to charge into Confederate territory without any supply line. He figured the area around Vicksburg was the South’s breadbasket and his men could forage for what they needed there, which they did. Grant was also entering Confederate territory with a huge river at his back—which had caused the Army of the Potomac considerable trouble—while going up against Confederates entrenched in strongly fortified positions. But the country desperately needed a major victory, and Grant felt he couldn’t withdraw his men in order to establish a supply depot at Memphis. Public opinion was already going against the war. If he retreated to start a new line of attack, he surmised that the public would be so discouraged that he would no longer receive new recruits or supplies and the Union cause would be lost. He determined to take the chance and do his best. Setting aside his reservations, Sherman was ready to forge ahead with him.

Grant knew Halleck would hate the idea, just as Sherman had, so he very carefully didn’t let the War Department know what he was doing. When they found out, Halleck tried to put a stop to it—but it was too late. Fortunately for Grant and the Union, his audacious plan worked. Vicksburg could be called Grant’s “perfect battle.”

LOST OPPORTUNITIES

General Joseph Johnston (See biography, page 46.)

Jefferson Davis, in The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, blamed Johnston for the loss of Vicksburg. In response, Johnston wrote an article in The North American Review placing the blame back on Jefferson Davis and on Lieutenant-General John Pemberton.

In the first half of July, 1862, General Halleck was ordered to Washington as general-in-chief. Before leaving Corinth he left General Grant in command of those holding in subjection northeastern Mississippi and southern West Tennessee. They numbered about forty-two thousand present for duty by Mr. Davis’s estimate. Their wide dispersion put them at the mercy of any superior or equal force, such as the Confederacy could have brought against them readily; but this opportunity, such a one as has rarely occurred in war, was put aside by the Confederate Government, and the army which, properly used, would have secured to the South the possession of Tennessee and Mississippi was employed in a wild expedition into Kentucky, which could have had only the results of a raid.

Mr. Davis extols the strategy of that operation, which, he says, “manoeuvred the foe out of a large and to us important territory.” This advantage, if it could be called so, was of the briefest. For this “foe” drove us out of Kentucky in a few weeks, and recovered permanently the “large and to us important territory.”

General Grant was then in northern Mississippi, with an army formed by uniting the detachments that had been occupying Corinth and various points in southern West Tennessee. He was preparing for the invasion of Mississippi, with the special object of gaining possession of Vicksburg. To oppose him, Lieutenant-General Pemberton, who commanded the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, had an active army of 23,000 effective infantry and artillery, and above 6,000 cavalry, most of it irregular. There were also intrenched camps at Vicksburg and Port Hudson, each held by about six thousand men, protecting batteries of old smooth bore guns, which, it was hoped, would prevent the Federal war vessels from occupying the intermediate part of the Mississippi. Lieutenant-General Holmes was then encamped near Little Rock with an army of above fifty thousand men. There were no Federal forces in Arkansas at the time, except one or two garrisons.

In all the time to which the preceding relates I had been out of service from the effects of two severe wounds received in the battle of Seven Pines [on June 1, 1862, when a bullet hit his shoulder and fragments from an exploding shell wounded his chest and thigh]. On the 12th of November, 1862, I reported myself fit for duty. The Secretary of War replied that I would be assigned to service in Tennessee and Mississippi in a few days. Thinking myself authorized to make suggestions in relation to the warfare in which I was to be engaged, I proposed to the Secretary, in his office, that, as the Federal forces about to invade Mississippi were united in that State, ours available for its defense should be so likewise; therefore General Holmes should be ordered to unite his forces with General Pemberton’s without delay.

As a reply, he read me a letter of late date from himself to General Holmes, instructing that officer to make the movement just suggested, and then a note from the President directing him to countermand his order to General Holmes. A few days after this, General Randolph resigned the office of Secretary of War—unfortunately for the Confederacy.

On the 24th of November Mr. Seddon, who had succeeded General Randolph as Secretary of War, assigned me to the command of the departments of General Bragg and Lieutenant-Generals E. Kirby Smith and Pemberton, each to command his department under me. In acknowledging this order, I again suggested the transfer of the army in Arkansas to Mississippi. The suggestion was not adopted or noticed.

On the 21st and 22d Mr. Davis inspected the water-batteries and land defenses of Vicksburg, which were then very extensive, but slight—the usual defect of Confederate engineering. He also conferred with the commander, Major-General Martin L. Smith, and me, in reference to the forces required to hold that place and Port Hudson, and at the same time to oppose General Grant in the field. We agreed (General Smith and I) that at least twenty thousand more troops were necessary, and I again urged him to transfer the troops in Arkansas to Mississippi. In a friendly note to General Holmes, which I was permitted to read, Mr. Davis pointed out to him that he would benefit the service by sending twenty thousand men into Mississippi, but gave him no order; consequently no troops came.

Thus an army outnumbering that which General Grant was then commanding was left idle, while preparations were in progress, near it, for the conquest of a portion of the Confederacy so important as the valley of the Mississippi.

The detaching of almost a fourth of General Bragg’s army to Mississippi, while of no present value to that department, was disastrous to that of Tennessee, for it caused the battle of Murfreesboro. General Rosecrans was, of course, soon informed of the great reduction of his antagonist’s strength, and marched from Nashville to attack him. The battle, that of Murfreesboro’ or Stone’s River, occurred on the 31st of December, 1862, and the 2d of January, 1863, and was one of the most obstinately contested and bloody of the war, in proportion to the numbers engaged. The result of this action compelled the Confederate army to fall back and place itself behind Duck River, at Manchester, Tullahoma, and Shelbyville.

Early in December, Grant projected an enterprise against Vicksburg under Sherman’s command. He directed that officer to embark at Memphis with about 30,000 men, descend the river with them to the neighborhood of the place, and with the cooperation of Admiral Porter’s squadron proceed to reduce it.

I immediately wrote to General Pemberton that, if invested in Vicksburg, he must ultimately surrender; and that, instead of losing both troops and place, he must save the troops by evacuating Vicksburg and marching to the north-east. The question of obeying this order was submitted by him to a council of war, which decided that “it was impossible to withdraw the troops from that position with such morale and material as to be of further service to the Confederacy.” This allegation was refuted by the courage, fortitude, and discipline displayed by that army in the long siege.

The so-called siege of Vicksburg was little more than a blockade. But one vigorous assault was made, which was on the third day.

He [Davis] accuses me of producing “confusion and consequent disasters” by giving a written order to Lieutenant-General Pemberton, which he terms opening correspondence. But as that order, dated May 13th, was disobeyed, it certainly produced neither confusion nor disaster. But “consequent disaster” was undoubtedly due to the disobedience of that order, which caused the battle of Champion’s Hill.

When that order was written, obedience to it, which would have united all our forces, might have enabled us to contend with General Grant on equal terms, and perhaps to win the campaign. Strange as it may now seem, Mr. Davis thought so at the time.

A proper use of the available resources of the Confederacy would have averted the disasters referred to by Mr. Davis. If, instead of being sent on the wild expedition into Kentucky, General Bragg had been instructed to avail himself of the dispersed condition of the Federal troops in northern Mississippi and west Tennessee, he might have totally defeated the forces with which General Grant invaded Mississippi three months later. Those troops were distributed in Corinth, Jackson, Memphis, and intermediate points, while his own were united, so that he could have fought them in detail, with as much certainty of success as can be hoped for in war. And such success would have prevented the military and naval combination which gave the enemy control of the Mississippi and divided the Confederacy, and would have given the Confederacy the ascendency on that frontier.

I do not know that there was any better than Joe Johnston. I have had nearly all of the Southern generals in high command in front of me, and Joe Johnston gave me more anxiety than any of the others. I was never half so anxious about Lee. By the way, I saw in Joe Johnston’s book that when I was asking Pemberton to surrender Vicksburg, he was on his way to raise the siege. I was very sorry. If I had known Johnston was coming, I would have told Pemberton to wait in Vicksburg until I wanted him, awaited Johnston’s advance, and given him battle. He could never have beaten that Vicksburg army, and thus I would have destroyed two armies perhaps. Pemberton’s was already gone, and I was quite sure of Johnston’s. I was sorry I did not know Johnston was coming until it was too late. Take it all in all, the South, in my opinion, had no better soldier than Joe Johnston—none at least that gave me more trouble.

—GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT

It is evident, and was so then, that the three bodies of Confederate troops in Mississippi in July, 1862, should have been united under General Bragg. The army of above 65,000 men so formed could not have been seriously resisted by the Federal forces.

Even after this failure the Confederates were stronger to repel invasion than the Federals to invade. By uniting their forces in Arkansas with those in Mississippi, an army of above 70,000 men would have been formed, to meet General Grant’s of 43,000. In all human probability such a force would have totally defeated the invading army, and not only preserved Mississippi but enabled us to recover Tennessee.

But if there were some necessity known only to the President to keep the Confederate troops then in Arkansas on that side of the Mississippi, he could have put General Pemberton on at least equal terms with his antagonist, by giving him the troops in April actually sent to him late in May. This would have formed an army of above fifty thousand men. General Grant landed two corps, less than 30,000 men, on the 30th of April and 1st and 2d of May; and it was not until the 8th of May that the arrival of Sherman’s corps increased his force to about 43,000 men. The Confederate reinforcements could have been sent as well early in April as late in May; and then, without bad generalship on our part, the chances of success would have been in our favor, decidedly.

RUNNING THE GAUNTLET

Admiral David Dixon Porter (See biography, page 14.)

The Army had already moved on the 10th of April, 1863, and that night was selected for the naval vessels to pass the batteries of Vicksburg.

Orders had been given that the coal in the furnaces should be well ignited, so as to show no smoke, that low steam should be carried, that not a wheel was to turn except to keep the vessel’s bow down river, and to drift past the enemy’s works fifty yards apart.

Most of the vessels had a coal barge lashed to them on the side away from the enemy, and the wooden gun-boat General Price, was lashed to the off side of the iron-clad Lafayette.

When all was ready the signal was made to get under way and the squadron started. The Benton, passed the first battery without receiving a shot, but as she came up with the second, the railroad station on the right bank of the river was set on fire, and tar barrels were lighted all along the Vicksburg shore, illuminating the river and showing every object as plainly as if it was daylight. Then the enemy opened his batteries all along the line, and the sharpshooters in rifle-pits along the levee commenced operations at the same instant. The fire was returned with spirit by the vessels as they drifted on, and the sound of falling buildings as the shells burst within them attested the efficiency of the gun-boats’ fire.

The vessels had drifted perhaps a mile when a shell exploded in the cotton barricades of the transport Henry Clay, and almost immediately the vessel was in a blaze; another shell soon after bursting in her hull, the transport went to pieces and sank. The Forest Queen, another transport, was also disabled by the enemy, but she was taken in tow by the Tuscumbia and conveyed safely through. The scene while the fleet was passing the batteries was grand in the extreme, but the danger to the vessels was more apparent than real. Their weak points on the sides were mostly protected by heavy logs which prevented many shot and shells going through the iron. Some rents were made but the vessels stood the ordeal bravely and received no damage calculated to impair their efficiency.

The enemy’s shot was not well aimed; owing to the rapid fire of shells, shrapnel, grape and canister from the gun-boats, the sharpshooters were glad to lay low, and the men at the great guns gave up in disgust when they saw the fleet drift on apparently unscathed.

They must have known that Vicksburg was doomed, for if the fleet got safely below the batteries their supplies of provisions from Texas would be cut off and they would have to depend on what they could receive from Richmond. General Steele had been sent up to the Steele’s Bayou region to destroy all the provisions in that quarter, and Pemberton knew that if Grant’s Army once got below Vicksburg it would eat up everything in the way of food between Warrenton and Bruinsburg.

Although the squadron was under fire from the time of passing the first battery until the last vessel got by, a period of two hours and thirty minutes, the vessels were struck in their hulls but sixty-eight times by shot and shells, and only fifteen men were wounded. At 2.30 a.m., all the vessels were safely anchored at Carthage, ten miles below Vicksburg, where was encamped the advanced division of the Army under General McClernand.

There was still work for the Navy to do in the Yazoo, while General Grant was starving the Confederates out in Vicksburg. The enemy now had to subsist on what provisions they had on hand, which was not much, and unless relieved by a superior force, a month more or less would bring about a surrender.

On the 19th of June, General Grant intended to open a general bombardment on the city at 4 a.m. and continue it until 10 o’clock. At the appointed time the bombardment commenced all along the army line and was joined on the water side by every gun-boat, the guns on scows and the mortars, until the earth fairly shook with the thundering noise. The gun-boats spread themselves all along in front of the city—cross firing on everything in the shape of a battery—but there was no response whatever—the works were all deserted.

After the fire was all over on the Union side, the city of Vicksburg was as quiet as the grave—not a soul could be seen. The women had all taken refuge in the shelters built in the hillsides, and every man that could hold a musket or point a bayonet was in the trenches. There they would stay for days and nights, lying in the mud and having what food they could get served out to them there.

The Civil War was fought in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, when tremendous technological advancements were taking place. As such, many consider the Civil War the first modern war.

The world was moving into a state of rapid change. Gas lighting for streetlights and homes was beginning to appear. The manufacturing boom, with the formation of corporations like Bethlehem Steel—in 1857 in Pennsylvania—led to the development of mass production, which in turn enabled the war effort to produce large quantities of munitions. Steam engines—particularly useful in hauling troops, supplies, artillery, and ammunition, both by railroads and steamships—had become common. The Union’s Army of the Potomac alone consumed 600 tons of food, supplies, and forage every day, much of which had to be transported to it in the South.

Advances in naval weapons and ammunition led to the ironclads. In the years before the war, eighteen- and twenty-four-pound guns were replaced by thirty-two- and sixty-eight-pounders, while ammunition evolved from solid shot to explosive and incendiary shells. These new armaments could do considerable damage to a wooden ship.

The Confederacy quickly realized it needed ironclads to break the Union blockade, while the Union needed some to protect its fleet. The first American ironclad used in battle9 was the Confederate ram CSS Manassas at the Battle of the Head of Passes in the Mississippi River Delta on October 12, 1861. The Union finished its first ironclad at the same time the Confederates finished their second. These two very different-looking ironclads clashed at the Battle of Hampton Roads, Virginia, on March 9, 1862.

The Confederate ship was previously known as the USS Merrimack. The Union scuttled it, so when repairing it the Confederates added an iron casement on top with sloping sides to protect the crew and their guns. Most of the later Confederate ironclads were of this type. The Confederate navy rechristened this ironclad ram the CSS Virginia, and it sank two Union ships and disabled a third the day before the USS Monitor arrived.

The Monitor had a very unusual design, with a flat deck that rose only about a foot above the waterline. It was designed to be a river battery but saw service at sea. It had only two guns, both of large caliber, mounted side by side in a revolving twenty-foot-wide turret. Its design was completely innovative. The navy called it the “iron pot.” One soldier fairly accurately described it as looking like a giant floating pumpkin seed with a round cheese box on top. At 172 feet long, it was smaller than the 275-foot Virginia but a lot more maneuverable. The Union had a lot riding on this odd ship, for if it had lost to the Virginia, the Union probably would have had to mine the Potomac River to keep the Confederates from sailing up it and shelling the White House.

The battle between the two ironclads came to a draw, but it clearly demonstrated that all other types of warships in the world were suddenly obsolete. Just days after the news reached England, the British Royal Navy canceled all its contracts for wooden ships, calling it madness to put any traditional ship into “an engagement with that little Monitor.”

The Confederacy had a total of about thirty-seven ironclads in its navy, while the Union had sixty-eight ironclads—forty-nine of them monitors—along with sixty tinclads, which were riverboats with thin sheet-metal armor. The Union also had timberclads, which used wood for armor, and cottonclads, which used bales of cotton. Like the Virginia, most of the South’s ironclads were rams with a pointed, reinforced extension on the bow that could sink ships by ramming into them.

Some of the Monitor’s protection came from being mostly underwater, since water greatly slows projectiles. Confederate engineers put this science to use by making submarine-shaped steamboats that maintained little more than their smokestack above the waterline. These were called torpedo boats because they were armed with a sixty- to seventy-pound “torpedo” or mine at the end of a spar. They rammed the mine into a ship below its waterline, attaching it to the ship by a barb on the tip of the spar. Then they pulled back until a trigger line attached to the mine became taut, detonating the mine. Powered with smokeless coal and used mainly on dark nights—making them doubly difficult to see—their main targets were ironclads. The Confederates had at least two of these torpedo boats and two other regular boats armed with spar mines. The Union developed two torpedo boats late in the war as well. These boats were first used off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, on the night of October 5, 1863, when the fifty-foot CSS David torpedo boat with a crew of four exploded its mine, damaging but not sinking the casement ironclad steamship USS New Ironsides.

Taking the idea of the torpedo boats a step further, the Confederates built what we now would call submarines but which they called diving torpedo boats.10 These arguably take second place as the most innovative invention of the war, right behind the Monitor. They seem to have built at least eight of them, although only two and possibly a third saw battle. Work on submarines was secretive, and records are incomplete, so there were probably other subs in use during the war.

Extremely unsafe, these early subs often sank. At least fifteen crewmen were killed in accidents, but the Confederates sent down divers in suits with large copper helmets to bring the subs back up, and they tried again. After the CSS H. L. Hunley submarine sank two or three times during testing, Beauregard quipped darkly: “’Tis more dangerous to those who use it than to enemy.”

Also known as “the Cigar Boat” and “the Fish Boat,” the Hunley, a forty-foot-long cylindrical vessel, had a propeller hand-cranked by a crew of eight men—one who also steered—and fore and aft hand-pumped ballast tanks enabling the sub to submerge and surface. Two short conning towers had escape hatches and small, two-inch-diameter viewing windows, four in the front tower and two in the back. It could dive for thirty minutes before needing to surface for air. The sub was armed with a 135-pound spar mine and was the first submarine to sink a ship in battle.

On the night of February 17, 1864, the Hunley exploded its mine, destroying the rear quarter of the ironclad USS Housatonic. The ship went down in five minutes, killing five of its crew. The Hunley was returning to port when it sank for the last time, once again killing its eight-man crew and proving Beauregard right.

On January 28, 1865, the seven-man, thirty-foot CSS Saint Patrick attacked USS Octorara in Mobile Bay, but its mine failed to explode. It was scuttled when the war ended. The Saint Patrick used steam power on the surface and was hand-cranked when underwater. Some consider it a David-class torpedo boat because of its smokestack, but it seems to have been able to submerge, so others classify it as a sub. Whether the smokestack could go all the way under remains unknown. Circumstantial evidence indicates that a similar sub, the CSS Captain Pierce, sank the monitor-class ironclad USS Tecumseh, but the official story is that the Tecumseh hit a mine.

As with many new weapons, the opposition didn’t like it. A Union commander of the blockade said he thought they should hang captured submariners “for using an engine of war not recognized by civilized nations.” Others called it “unchivalrous.” But that didn’t stop the North from building its own subs.

Designed by a French inventor, the forty-seven-foot USS Alligator was rowed by a series of oars with a twenty-two-man crew. Interestingly, this sub had an air-purifying system, a diver’s chamber, and air compressors for air renewal. The compressors also pumped air to a diver who could leave the sub to attach a limpet mine to the target ship, which would then be electrically detonated.

The Alligator was launched on May 1, 1862, its first mission to destroy a bridge over the Appomattox River and clear obstructions in the James River, but the rivers were too shallow for the sub to submerge. Union strategists wanted to use it against the CSS Virginia II, but tests determined the sub to be unsafe. The propulsion system changed from oars to a screw propeller, which only required an eight-man crew. President Lincoln witnessed a demonstration of the sub’s capabilities, but less than a month later, in April 1863, it was lost at sea off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

Speculators attempted to interest the Union navy in a twenty-nine-foot sub called The Intelligent Whale, but the Navy refused to buy it, nor was it completed until after the war. Another sub, the Explorer, was pressurized with an open bottom for divers, but the government wasn’t interested, so a pearl-diving company bought it.

ASSAULT OR SIEGE

General Ulysses S. Grant (See biography, page 54.)

We were now assured of our position between [the Confederate armies of ] Johnston and Pemberton, without a possibility of a junction of their forces. Pemberton might have made a night march and, by moving north on the west side, have eluded us and finally returned to Johnston. But this would have given us Vicksburg. It would have been his proper move, however, and the one Johnston would have made had he been in Pemberton’s place. In fact it would have been in conformity with Johnston’s orders to Pemberton.

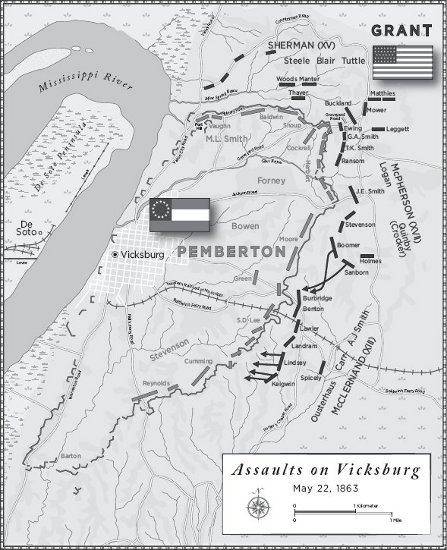

On the 19th [May 1863] there was constant skirmishing with the enemy while we were getting into better position. The enemy had been much demoralized by his defeats at Champion’s Hill and the Big Black, and I believed he would not make much effort to hold Vicksburg. Accordingly, at two o’clock I ordered an assault. It resulted in securing more advanced positions for all our troops where they were fully covered from the fire of the enemy.

I now determined on a second assault [on the 22nd]. Johnston was in my rear, only fifty miles away, with an army not much inferior in numbers to the one I had with me, and I knew he was being reinforced. There was danger of his coming to the assistance of Pemberton, and after all he might defeat my anticipations of capturing the garrison if, indeed, he did not prevent the capture of the city. The immediate capture of Vicksburg would save sending me the reinforcements which were so much wanted elsewhere, and would set free the army under me to drive Johnston from the State. But the first consideration of all was—the troops believed they could carry the works in their front, and would not have worked so patiently in the trenches if they had not been allowed to try.

The attack was ordered to commence on all parts of the line at ten o’clock a.m. on the 22d with a furious cannonade from every battery in position. The attack was gallant, and portions of each of the three corps succeeded in getting up to the very parapets of the enemy and in planting their battle flags upon them; but at no place were we able to enter. General McClernand reported that he had gained the enemy’s intrenchments at several points, and wanted reinforcements. I occupied a position from which I believed I could see as well as he what took place in his front, and I did not see the success he reported. But his request for reinforcements being repeated I could not ignore it, and sent him Quinby’s division of the 17th corps. Sherman and McPherson were both ordered to renew their assaults as a diversion in favor of McClernand, This last attack only served to increase our casualties without giving any benefit whatever.

I now determined upon a regular siege—to “outcamp the enemy,” as it were, and to incur no more losses. The experience of the 22d convinced officers and men that this was best, and they went to work on the defences and approaches with a will.

MCCLERNAND AND THE SECOND ASSAULT

General William Tecumseh Sherman (See biography, page 4.)

After our men had been fairly beaten back from off the parapet, and had got cover behind the spurs of ground close up to the rebel works, General Grant came to where I was, on foot, having left his horse some distance to the rear. I pointed out to him the rebel works, admitted that my assault had failed, and he said the result with McPherson and McClernand was about the same.

While he was with me, an orderly or staffofficer came and handed him a piece of paper, which he read and handed to me. I think the writing was in pencil, on a loose piece of paper, and was in General McClernand’s handwriting, to the effect that “his troops had captured the rebel parapet in his front,” that “the flag of the Union waved over the stronghold of Vicksburg,” and asking him (General Grant) to give renewed orders to McPherson and Sherman to press their attacks on their respective fronts, lest the enemy should concentrate on him (McClernand).

General Grant said, “I don’t believe a word of it”; but I reasoned with him, that this note was official, and must be credited, and I offered to renew the assault at once with new troops. He said he would instantly ride down the line to McClernand’s front, and if I did not receive orders to the contrary, by 3 o’clock p.m., I might try it again. Mower’s fresh brigade was brought up under cover, and, punctually at 3 p.m., hearing heavy firing down along the line to my left, I ordered the second assault. It was a repetition of the first, equally unsuccessful and bloody. It also transpired that the same thing had occurred with General McPherson, who lost in this second assault some most valuable officers and men, without adequate result; and that General McClernand, instead of having taken any single point of the rebel main parapet, had only taken one or two small outlying lunettes open to the rear, where his men were at the mercy of the rebels behind their main parapet, and most of them were actually thus captured This affair caused great feeling with us, and severe criticisms on General McClernand, which led finally to his removal from the command of the Thirteenth Corps, to which General Ord succeeded.

The immediate cause, however, of General McClernand’s removal was the publication of a sort of congratulatory order addressed to his troops, first published in St. Louis, in which he claimed that he had actually succeeded in making a lodgment in Vicksburg, but had lost it, owing to the fact that McPherson and Sherman did not fulfill their parts of the general plan of attack. This was simply untrue. The several assaults made May 22d, on the lines of Vicksburg, had failed, by reason of the great strength of the position and the determined fighting of its garrison.

FORCING A SURRENDER

General Ulysses S. Grant (See biography, page 54.)

We were now looking west, besieging Pemberton, while we were also looking east to defend ourselves against an expected siege by Johnston. But as against the garrison of Vicksburg we were as substantially protected as they were against us. Where we were looking east and north we were strongly fortified, and on the defensive. Johnston evidently took in the situation and wisely, I think, abstained from making an assault on us because it would simply have inflicted loss on both sides without accomplishing any result. We were strong enough to have taken the offensive against him; but I did not feel disposed to take any risk of losing our hold upon Pemberton’s army, while I would have rejoiced at the opportunity of defending ourselves against an attack by Johnston.

From the 23d of May the work of fortifying and pushing forward our position nearer to the enemy had been steadily progressing. At three points on the Jackson road, in front of Leggett’s brigade, a sap [i.e., a deep trench] was run up to the enemy’s parapet, and by the 25th of June we had it undermined and the mine charged. The enemy had countermined, but did not succeed in reaching our mine. At this particular point the hill on which the rebel work stands rises abruptly. Our sap ran close up to the outside of the enemy’s parapet. In fact this parapet was also our protection. The soldiers of the two sides occasionally conversed pleasantly across this barrier; sometimes they exchanged the hard bread of the Union soldiers for the tobacco of the Confederates; at other times the enemy threw over hand-grenades, and often our men, catching them in their hands, returned them.

Our mine had been started some distance back down the hill; consequently when it had extended as far as the parapet it was many feet below it. This caused the failure of the enemy in his search to find and destroy it. On the 25th of June at three o’clock, all being ready, the mine was exploded. A heavy artillery fire all along the line had been ordered to open with the explosion. The effect was to blow the top of the hill off and make a crater where it stood.

The breach was not sufficient to enable us to pass a column of attack through. In fact, the enemy having failed to reach our mine had thrown up a line farther back, where most of the men guarding that point were placed. There were a few men, however, left at the advance line, and others working in the countermine, which was still being pushed to find ours. All that were there were thrown into the air, some of them coming down on our side, still alive.

As soon as the explosion took place the crater was seized by two regiments of our troops who were near by, under cover, where they had been placed for the express purpose. The enemy made a desperate effort to expel them, but failed, and soon retired behind the new line. From here, however, they threw hand-grenades, which did some execution. The compliment was returned by our men, but not with so much effect. The enemy could lay their grenades on the parapet, which alone divided the contestants, and roll them down upon us; while from our side they had to be thrown over the parapet, which was at considerable elevation.

During the night we made efforts to secure our position in the crater against the missiles of the enemy, so as to run trenches along the outer base of their parapet, right and left; but the enemy continued throwing their grenades, and brought boxes of field ammunition [shells], the fuses of which they would light with port-fires, and throw them by hand into our ranks.

We found it impossible to continue this work. Another mine was consequently started which was exploded on the 1st of July, destroying an entire rebel redan [a V-shaped projection from the line], killing and wounding a considerable number of its occupants and leaving an immense chasm where it stood. No attempt to charge was made this time, the experience of the 25th admonishing us. Our loss in the first affair was about thirty killed and wounded. The enemy must have lost more in the two explosions than we did in the first. We lost none in the second.

From this time forward the work of mining and pushing our position nearer to the enemy was prosecuted with vigor, and I determined to explode no more mines until we were ready to explode a number at different points and assault immediately after.

The picket lines were so close to each other that the men could converse. On the 21st of June I was informed, through this means, that Pemberton was preparing to escape, by crossing to the Louisiana side under cover of night; that he had employed workmen in making boats for that purpose; that the men had been canvassed to ascertain if they would make an assault on the “Yankees” to cut their way out; that they had refused, and almost mutinied, because their commander would not surrender and relieve their sufferings, and had only been pacified by the assurance that boats enough would be finished in a week to carry them all over., The rebel pickets also said that houses in the city had been pulled down to get material to build these boats with. Afterwards this story was verified: on entering the city we found a large number of very rudely constructed boats.

All necessary steps were at once taken to render such an attempt abortive.

On the night of the 1st of July, Johnston was between Brownsville and the Big Black, and wrote Pemberton from there that about the 7th of the month an attempt would be made to create a diversion to enable him to cut his way out. Pemberton was a prisoner before this message reached him.

I rode into Vicksburg with the troops, and went to the river to exchange congratulations with the navy upon our joint victory. At that time I found that many of the citizens had been living under ground.

The ridges upon which Vicksburg is built are composed of a deep yellow clay of great tenacity. Many citizens secured places of safety for their families by carving out rooms in these embankments. A door-way in these cases would be cut in a high bank starting from the level of the road or street, and after running in a few feet a room of the size required was carved out of the clay, the dirt being removed by the door-way. In some instances I saw where two rooms were cut out, for a single family, with a door-way in the clay wall separating them. Some of these were carpeted and furnished with considerable elaboration. In these the occupants were fully secure from the shells of the navy, which were dropped into the city night and day without intermission.

One man had his head blown off while in the act of picking up his child. Many strange escapes and incidents are spoken of—so many that they have not been specially noticed. One shell fell and exploded between two officers as they were riding together on the street, and lifted both horses and riders into the air without hurting either man or beast. One woman had just risen from her chair when a shell came through the roof, took her seat and shattered the house without injuring the lady; and a hundred others of similar cases. A little girl, the daughter of Mr. Jones, was sitting at the entrance of a cave, when a Parrott shell entered the portal and took her head right off.

—FROM THE DIARY OF A VICKSBURG CITIZEN

The men of the two armies fraternized as if they had been fighting for the same cause. When they passed out of the works they had so long and so gallantly defended, between lines of their late antagonists, not a cheer went up, not a remark was made that would give pain. Really, I believe there was a feeling of sadness just then in the breasts of most of the Union soldiers at seeing the dejection of their late antagonists.

Having cleaned up about Vicksburg and captured or routed all regular Confederate forces for more than a hundred miles in all directions, I felt that the troops that had done so much should be allowed to do more before the enemy could recover from the blow he had received, and while important points might be captured without bloodshed. I suggested to the General-in-chief the idea of a campaign against Mobile, starting from Lake Pontchartrain.

Halleck disapproved of my proposition to go against Mobile, so that I was obliged to settle down and see myself put again on the defensive as I had been a year before in west Tennessee. It would have been an easy thing to capture Mobile at the time I proposed to go there. Having that as a base of operations, troops could have been thrown into the interior to operate against General Bragg’s army. This would necessarily have compelled Bragg to detach in order to meet this fire in his rear. If he had not done this the troops from Mobile could have inflicted inestimable damage upon much of the country from which his army and Lee’s were yet receiving their supplies.

The General-in-chief having decided against me, the depletion of an army, which had won a succession of great victories, commenced, as had been the case the year before after the fall of Corinth when the army was sent where it would do the least good.

In a private letter in 1884, Grant wrote:

The fact is, General Pemberton, being a Northern man commanding a Southern army, was not at the same liberty to surrender an army that a man of Southern birth would be. In adversity or defeat he became an object of suspicion, and felt it. [General John] Bowen was a Southern man all over, and knew the garrison of Vicksburg had to surrender or be captured, and knew it was best to stop further effusion of blood by surrendering. He did all he could to bring about that result.

It was Bowen that proposed that he and A. J. Smith should talk over the matter of the surrender and submit their views. Neither Pemberton nor I objected, but we were not willing to commit ourselves to accepting such terms as they might propose. In a short time those officers returned. Bowen acted as spokesman; what he said was substantially this: The Confederate army was to be permitted to march out with the honors of war, carrying with them their arms, colors, and field-batteries. The National troops were then to march in and occupy the city, and retain the siege-guns, small-arms not in the hands of the men, all public property remaining.

Of course I rejected the terms at once. I did agree, however, before we separated, to write Pemberton what terms I would give. I was very glad to give the garrison of Vicksburg the terms I did. There was a cartel in existence at that time which required either party to exchange or parole all prisoners either at Vicksburg or at a point on the James River within ten days after captures or as soon thereafter as practicable. This would have used all the transportation we had for a month. The men had behaved so well that I did not want to humiliate them. I believed that consideration for their feelings would make them less dangerous foes during the continuance of hostilities, and better citizens after the war was over.

In a conversation that later appeared in print with Grant’s corrections and approval, he said:

War has responsibilities that are either fatal to a commander’s position or very successful. I often go over our war campaigns and criticise what I did, and see where I made mistakes. Information now and then coming to light for the first time shows me frequently where I could have done better. I don’t think there is one of my campaigns with which I have not some fault to find, and which, as I see now, I could not have improved, except perhaps Vicksburg. I do not see how I could have improved that.

When I determined on that campaign, I knew, as well as I knew anything, that it would not meet with the approval of the authorities in Washington. I knew this because I knew Halleck, and that he was too learned a soldier to consent to a campaign in violation of all the principles of the art of war. But I felt that every war I knew anything about had made laws for itself, and early in our contest I was impressed with the idea that success with us would depend upon our taking advantage of new conditions. No two wars are alike, because they are generally fought at different periods, under different phases of civilization.

To take Vicksburg, according to the rules of war as laid down in the books, would have involved a new campaign, a withdrawal of my forces to Memphis, and the opening of a new line of attack. The North needed a victory. We had been unfortunate in Virginia, and we had not gained our success at Gettysburg. Such a withdrawal as would have been necessary—say to Memphis, would have had all the effects, in the North, of a defeat.

I talked it over with Sherman. I told him it was necessary to gain a success in the south-west, that the country was weary and impatient, that the disasters in Virginia were weakening the government, and that unless we did something, there was no knowing what, in its despair, the country might not do. Lee was preparing to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania, as he did. Sherman said that the sound campaign was to return to Memphis, establish that as a base of supplies, and move from there on Vicksburg, building up the road as we advanced and never uncovering that base.

I felt that what was wanted was a forward movement to a victory that would be decisive. In a popular war we had to consider political exigencies. You see there was no general in our army who had won that public confidence which came to many of them afterward. We were—all of us, more or less—on probation. Sherman contended that the risk of disaster in the proposed movement was so great that even for my own fame I should not undertake it; that if I failed the administration, about which I was worrying so much, would root me up and throw me away as a useless weed. I thought that war anyhow was a risk; that it made little difference to the country what was done with me. I might be killed or die from fever. The more I thought of it the more I felt that my duty was plain. I felt, however, that to carry out my move fully I must have it developed before it could be stopped from Washington, before orders could come—as they did in fact come—that would have rendered it impossible.

Instead of making a report to Washington of what had been done thus far, I hurried into the interior and developed my movement. You know the theory of the campaign was to throw myself between Johnston and Pemberton, prevent their union, beat each army separately if I could, and take Vicksburg.

An officer came into my lines from Banks’s army, then investing Port Hudson. This officer was a brigadier-general, in a high state of excitement, a small and impressive man, so overcome with the sense of his tremendous responsibility that he seemed to stand on his toes to give it emphasis. He had the order from Halleck for me to withdraw at once with my force and join Banks. This order was so important that he, a general officer, had come all the way to bring it and to escort me, if necessary, to Port Hudson. I acknowledged the order, but said I was there in front of the enemy and engaged, and could not withdraw; that even General Halleck, under the circumstances, would not expect me to do so.

The little brigadier, standing on his toes, became more and more emphatic. I pointed out that we were not only engaged with the enemy, but winning a victory, and that General Halleck never intended his order to destroy a victory.

If the Vicksburg campaign, meant anything, in a military point of view, it was that there are no fixed laws of war which are not subject to the conditions of the country, the climate, and the habits of the people. The laws of successful war in one generation would insure defeat in another.

Pemberton could not have held Vicksburg a day longer than he did. But desperate as his condition was, he did not want to surrender it. He knew that, as a Northern man by birth, he was under suspicion; that a surrender would be treated as disloyalty, and rather than incur that reproach he was willing to stand my assault. But as I learned afterward his officers, and even his men, saw how mad would have been such a course, and he reluctantly accepted the inevitable.

I could have carried Vicksburg by assault, and was ready when the surrender took place. But if Pemberton had forced this, had compelled me to throw away lives uselessly, I should have dealt severely with him. It would have been little less than murder, not only of my men but his own. I would severely punish any officer who, under such circumstances, compelled a wanton loss of life. War is war, and murder is murder, and Vicksburg was so far reduced, and its condition so hopeless when it surrendered, that the loss of another life in defending it would have been criminal.