Is the 20th century career woman an American invention? If not, she still is clearly a symbol of the nation’s move into the future in the wake of WWI. Beginning in the 1920s, women began entering the workforce in greater numbers. As the focus of American life shifted from rural to urban areas, big city “working girls” would replace doe-eyed farm lasses as the heroines in popular entertainment. The feisty career women of ’30s Hollywood movies played by Barbara Stanwyck and Rosalind Russell had quick wits and sharp tongues, and needed both to compete with men and prove their worth. Newspaper comic strips like Winnie Winkle the Breadwinner and Brenda Starr, Reporter featured the new heroines of the day—smart, independent, and emancipated. Their high-heeled feet walked magnificent avenues lined with towering skyscrapers, as they scanned the horizon in search of their destinies.

Lois Lane is the original career woman of the comic book world. She made her debut in 1938 as a Hollywood style dame with brains, guts and beauty. But aside from Lois Lane, the common perception of the comic book female is that of the scantily clad, masked superheroine. So, it might be surprising to many that in the early years of comics, there were a large number of career woman, from all walks of life, who starred in their own features in anthology titles.

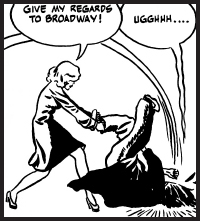

Many of the masked female crimefighters of the Golden Age were wealthy debutantes who had the time and money to go running across rooftops in a costume in search of adventure. Even their names indicated their upper crust pedigrees—Sandra Knight was the Phantom Lady, Marla Drake was Miss Fury, Anita Morgan was The Purple Tigress. The working girls of the comics were strictly working class, and their names showed it— Sally O’Neil, Penny Wright, Betty Bates, Patty O’Day. These women didn’t have the luxury of maintaining a secret identity. They needed to earn a living. That’s not to say that they didn’t have adventures or right wrongs. These flinty dames sent their share of evildoers to jail, but they didn’t use magic rings or ray projectors or antigravity helmets. They used their brains, and a good right hook.

Unlike the secretaries that populated the newspaper comic strips, the working girls of comic books had professions that provided danger and intrigue as story fodder. Following in the mold of Lois Lane, there were a number of lady reporters—Penny Wright, Betty Boyd, Joan Mason, Molly O’Moore. There were also a slew of intrepid news photographers like Fran Frazer, Gail Porter, Patty O’Day and the Blonde Bomber who risked death to get a scoop. Sally O’Neil, Jeanette Copeland, and Lucky Dale were all policewomen, while Bonnie Hawks and Calamity Jane ran detective agencies. The most unexpected comic book heroine was Betty Bates, Lady at Law, a shrewd attorney with jiu jitsu skills.

In the world of superhero comics, male heroes have often said that fighting evil is no job for a woman. In the 1940s, even the all-powerful Wonder Woman was only allowed to be the Justice Society’s secretary, while her male teammates had all of the adventures. The career women in these stories don’t take a backseat to anyone. They are portrayed as competent and professional, never as hapless females trying to do a man’s job and failing miserably. Simply, they aren’t treated as jokes. They’re resourceful and don’t need a man to rescue them. And these women didn’t balk at the idea of competing with a man, either. Some of them were even the bosses of men. The focus of their stories was action and adventure, not romance. These heroines are not shown biding their time waiting for a marriage proposal so that they can retire.

So what happened to these daring career women? Well, times changed, and tastes changed. When superheroes fell out of the fashion in the late ’40s and early ’50s, many of the anthology titles folded, or were changed into other genres that were becoming more popular, like westerns, horror, and romance. There was no longer a place for clever career women. By the 1950s, there were only two career women in comics. Marvel Comics published Millie the Model, which focused on humor, romance, and glamour. And Lois Lane was still around. Starting in 1958, she starred in her own title, Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane. But these stories focused less on Lois as a reporter and more on her ongoing efforts to trap Superman into marriage. A moment in time had ended. It wasn’t until the 1980s, and heroines like the tough private detective Ms. Tree, that regular women who didn’t wear costumes would make a comeback in comics.

So now, let’s take a look at the women who didn’t need to wear a mask to fight the bad guys—

* * *

PENNY WRIGHT, FEATURE WRITER—Newspaper reporter Penny Wright’s quest for her next big story took her all over the globe. She was a take-charge woman who tangled with Latin American revolutionaries and European spies. Like many of the pre-WWII comics, Penny’s rollicking stories were reminiscent of the pulp magazines. As soon as daredevil Penny had managed to get herself out of a scrape, she was back at her typewriter, banging out her latest scoop that would send an evildoer to jail. Penny Wright represents that early 20th century image of the American woman as the modern and independent firebrand, committed to exposing the truth. “Miss Wright, you American girls certainly have spunk and brains,” says a gendarme at the end of the story presented here. Penny Wright appeared in only three stories in 1940s Champion Comics.

BETTY BATES, LADY AT LAW—Despite being an attorney, Betty Bates often wound up taking the law into her own hands. The lady lawyer seemed to spend more time investigating cases than she did in the courtroom. Even though educated Betty had her law degree, readers knew that this tough dame hadn’t completely left her working class roots behind. “Listen sister…law isn’t the only subject I’ve mastered!” snaps Betty, as she swats the face of a gun moll. “I may be a Portia, but my middle name’s Dempsey!” Eventually Betty became district attorney, and gained a sidekick in the form of Larry, a reporter. But even with a male sidekick, Betty remained the star of the show, appearing in Hit Comics for an impressive run from 1940–50.

THE BLONDE BOMBER—Honey Blake was a blonde, but she was no dummy. As an intrepid camerawoman for Acme Newsreels, Honey combined “glamour and daring” in her pursuit of the biggest new stories, aided by her tubby assistant Jimmy Slapso. As the “fotographic furies,” Honey and Slapso’s assignments took them around the world; the two encountering criminals and Nazi spies along the way. Daredevil Honey was as quick with her fists as she was with her camera. But as the story presented here also points out, “Honey’s character has many facets—in her laboratory she’s an expert chemist…” The Blonde Bombers was a regular feature in Green Hornet Comics from 1942–47. In their final adventures, Honey and Slapso, no longer content to merely travel the world, now travelled through time in search of adventure. The Blonde Bomber also appeared in All-New Comics and Speed Comics. This story was drawn by artist Barbara Hall.

JILL TRENT, SCIENCE SLEUTH—Jill Trent may have been ahead of her time. First off, she was the proto girl geek of comics—a scientist who spent her time in the lab happily concocting fantastic creations like x-ray glasses and indestructible cloth. Second, Jill didn’t have a boyfriend, but she did have her best friend and trusty assistant Daisy. On occasion, the girls were shown sharing a bed, suggesting this series may have been forward thinking in more ways than one. Jill and Daisy were always getting mixed up in criminal cases, which they solved using Jill’s inventions, along with the pistols they always seemed to be packing. In this story, Jill whips up the instruments of her and Daisy’s salvation from odds and ends, à la ’80s TV hero “MacGyver.” Jill Trent, Science Sleuth appeared in Fighting Yank and Wonder Comics from 1943–48.

CALAMITY JANE—When you think of the hard-boiled detectives of 1940s noir stories, you picture a guy who’s rough around the edges, maybe a little down on his luck, quick to get into a fight, cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth. But you don’t necessarily think of a woman. If that’s the case, meet Calamity Jane. “I’m a detective in skirts! In the books I’m Jane Janis, private investigator…but to the cops I’m misery—so they call me Calamity…” No doubt about it, Calamity was a tough cookie. Her stories reflect the film noir inspired comics of the postwar era that had a cynicism not seen a few years earlier. Artist Bill Draut appeared in each story, as Calamity herself recounted her latest adventure for him to use in his next comic book. Calamity’s assistant was a dim-witted cab driver named Hack who chauffeured her around town. The dialogue in this story is superb, with Calamity Jane dispensing one acid tongued barb after another. Calamity Jane appeared in Boy Explorers Comics and Green Hornet Comics from 1946–47.