Jonah in Nineveh (3:1–10)

Visit required three days (3:3). The word translated “visit” here can be understood in a variety of ways. In Nehemiah 2:6 it refers to how long it would take Nehemiah to do the specified job rather than how far he had to go. Parallel terminology in Assyrian literature has the same flexibility and can refer to straight-line distance, a circuitous route, or to the time spent on a task.27 Add to this the possibility that there is some ambiguity as to whether the city or the province is referred to (see the sidebar “Nineveh”), and it becomes clear that the three-day designation is appropriate.

Forty more days and Nineveh will be overturned (3:4). The oracles of the prophets of the ancient Near East are typically ones of instruction and encouragement for the king.28 There is some indictment (usually cultic matters left undone), but little attestation of judgment oracles against the king who is being addressed. In the only possible exception there is an oracle against Zimri-Lim: “A devouring (plague) will take place. Issue a claim against the cities that they return the sacred things. The man who has committed violence let them expel from the city.”29 Occasionally a prophet will proclaim judgment on an enemy of the king, such as: “Into the net which he ties, I will gather him. His city I will destroy, and his treasure, which is from ancient times, I will surely plunder.”30

In contrast, prophecies of impending judgment are common in the OT. There is no suggestion in this text that Jonah offered indictment (e.g., of their idolatry), instruction (e.g., in the law), encouragement, or hope (e.g., for deliverance). The prophet’s role should not be confused with the missionary’s. Unlike the missionary, who has a message of hope (the gospel) and who comes hoping to see conversion, the prophet has whatever message God has given him and comes only to deliver it.

The Ninevites believed God (3:5). The text only indicates that the Ninevites believe the message of impending doom that Jonah has delivered. In the prophecy texts from Mari in the eighteenth century B.C., we get a glimpse of the authentication procedures. If the message came from an unknown prophet, something like the imprint of the hem of his or her garment was provided to the king for authentication of the prophecy. More important, the substance of the message would be confirmed by other divination procedures.31

In these procedures of the ancient Near East, thev practitioners preferred to have omens or messages confirmed through at least two different procedures. Omens could be read from the movement of the heavenly bodies, from the actions of animals or the flight of birds, or from the configurations of the entrails of sacrificial animals, just to name a few. Once it was determined to their satisfaction that this was a legitimate divine message, they would have accepted it and responded. Most likely the Ninevites confirm Jonah’s message before their response.

The Ninevites would not necessarily ask why they are going to be destroyed. The literature indicates that in Mesopotamia they did not think that they could know the reasons or even whether there were reasons. In a lamentation over the fall of the city of Ur, Sin, the patron deity of the city, asks why it was overthrown. The answer is given by Enlil, the head of the Pantheon:

The judgment of the assembly cannot be turned back,

The word of An and Enlil knows no overturning,

Ur was indeed given kingship (but) it was not given an eternal reign.

From time immemorial, since the land was founded, until the population multiplied

Who has ever seen a reign of kingship that would take precedence (forever)?

The reign of its kingship had been long indeed but had to exhaust itself.32

Despite their acceptance of the veracity of Jonah’s message and their sincere response, they are still polytheistic Assyrians ignorant of the nature of Israel’s law, faith, and God.33

Declared a fast … put on sackcloth (3:5). The Akkadian term for sackcloth is bašāmu. The most relevant usage of it is in an Esarhaddon inscription, in which he is said to have “wrapped his body in sackcloth befitting a penitent sinner.”34 Note also the Adad-Guppi autobiography in which the mother of Nabonidus says: “In order to appease the heart of my god and my goddess, I did not put on a garment of excellent wool, silver, gold, a fresh garment; I did not allow perfumes (or) fresh oil to touch my body. I was clothed in a torn garment. My fabric was sackcloth.”35

Fasting is much more difficult to attest. While fasting is not detectable in religious rituals or for repentance in Mesopotamia,36 individuals did occasionally refrain from eating and drinking in mourning rites.37 In addition, there were special dietary instructions for certain days throughout the Babylonian year.38 Other occasions when the Mesopotamians did not eat or drink seem to be similar to the situation recorded in Acts 23:12, when a group of men vowed not to eat or drink until they had killed the apostle Paul.39 While these may be called fasting, there are no obvious spiritual or cultic connections to the act.

King of Nineveh (3:6). The gravest problem with the king of Assyria being called the king of Nineveh is that during the time of Jonah, the king of Assyria did not have his residence at Nineveh. Though Nineveh may have been a large and important city, it was not a royal city. Jonah would not have encountered the king of Assyria on his throne in Nineveh, because the king of Assyria did not have a throne there.

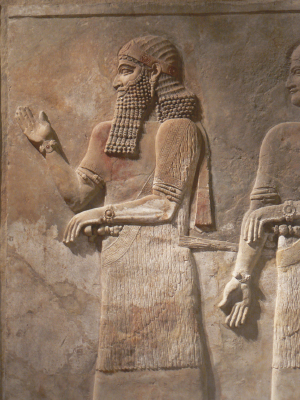

Relief of Adad-Nirari III

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

A more likely interpretation is that the “king of Nineveh” is not the king of Assyria, but a governor or noble ruling the city/province. During Jonah’s lifetime, the Assyrian empire was in a state of practical anarchy. The kings of Assyria during this period reigned through an oligarchy of four powerful officials.40 The inscriptional evidence from various provincial governors during this time shows that those of the western provinces displayed a tendency to independence during and after the reign of Adad-Nirari III. With Urartu growing strong, infiltrating into contiguous countries and disrupting Assyria’s trade routes,41 the king was sustaining military defeats and encouraged his governors to take the initiative. Adad-Nirari gave large tracts of land as well as privileges and prerogatives to various nobles.42 Specifics regarding Nineveh are not clear since this period in Assyrian history is so poorly attested, but all of this favors the possibility that administrative districts such as Nineveh could operate somewhat independently.

Concerning terminology, the Hebrew term translated “king” in Jonah (melek), though used throughout the OT for kings, does not pose an insuperable problem when we consider that an Assyrian official is being described. The normal Akkadian (Assyrian) word for king is šarru, but the bilingual inscription from Tell Fekheriye translates the Akkadian šaknu (“governor”) with the Aramaic mlk.43 This suggests that West Semitic languages (Aramaic and Hebrew) could use this word to refer to local ruling governors or nobles. Furthermore, the governor (šaknu/mlk) could rule over either the city of Nineveh or the province of Nineveh. In fact, in the limmu list of Assyrian notables, the designated official for the year 761 was Nabu-mukin-ahi, governor of the region of Nineveh.44

Decree (3:7–9). The proclamation of the king details the strategies for appeasing the angry god. Aside from the rituals of sackcloth and fasting discussed above, he dictates some behavioral changes. Though Assyrians had no revelation from their gods that equated to Israel’s covenant law, they understood that justice was important to the gods for the order that it brought to society. Lawlessness was offensive to the gods, so here the Assyrians act to remedy that condition. It is possible that various rituals are performed in order to appease God or protect them from destruction. To whatever extent such rituals may have been pursued, the text has no interest in them. God is responding to their humility and their repentance, not to their rituals (which would have been attempts at manipulation).

Beast covered with sackcloth (3:8). That even beasts should be adorned with the signs of repentance is not outlandish. Even today black hearses are used by funeral parlors, and horses in funeral procession feature black accessories. Since sackcloth itself is not frequently attested in ancient literature, it is no surprise that we have no examples of animals being draped with it. The book of Judith (4:10–12), however, contains an example of the Jews responding in a similar way when Holofernes marched on Jerusalem. In addition, Herodotus notes that Persian customs included horses in mourning by cutting their manes just as the people shaved their heads.45

He had compassion (3:10). God’s action has been translated in various ways (NASB: “relented,” KJV: “repented,” NRSV: “changed his mind”). This is one of the main passages that generates discussion about whether God can change his mind. In the ancient Near East the gods were erratic and could be managed through various ritual approaches. The gods were believed to have needs, and when humans met those needs, they were attempting to soothe the god from any irritation and earn his goodwill. It was therefore the desired intention of human beings to induce a god to change his mind concerning how he was treating them. This mutual dependence is the fulcrum of the Assyrian religious system.

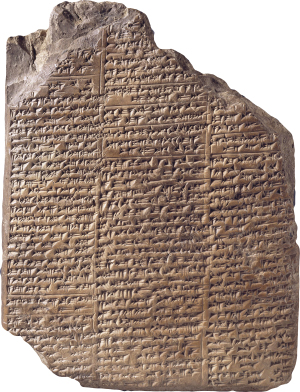

Inanna on the Warka vase who is praised for being one whose decrees cannot be changed

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, Iraq Museum, Baghdad

It strikes our religious sensibilities as inherently corrupt in that it assumes a picture of a god who acts out of caprice rather than conviction and whose needs can be exploited or whose plans can be subverted through manipulation. It would therefore be easy for us to share Jonah’s theological indignation (4:2) that God should be willing to be perceived as part of such a corrupted system. Why would God allow himself to be so misconstrued?

When the biblical text insists that God is not one to change his mind (Num. 23:19; 1 Sam. 15:29, both using the same verb as Jon. 3:10), it is in the context of covenant agreements, not the outcome of prophetic pronouncements (see Jer. 18:8). Mesopotamians also confirm that what their gods decree cannot be altered: “What you proclaim in the assembly, An and Enlil cannot throw out; the oracles uttered on your tongue never change in heaven or earth; A place you sanction meets no ruin; A place you brand does not last.”46 There is a distinction to be made, then, between ad hoc action, which could be impacted by “gifts” to the deity, and formal divine decrees, which could not be altered. Confusion sometimes existed regarding which category a prophetic pronouncement belonged in.

As the next chapter in Jonah explains, God’s action to postpone judgment does not suggest that he can be manipulated or is part of a corrupt system. Despite what the Assyrians may think or intend, his response is intended as a demonstration of his compassion.