An Unjust World in Light of a Hopeful Future (6:1–7:20)

Plead your case (6:1–2). Micah depicts a courtroom, drawing on the covenant ratification language also visible in Deuteronomy (Deut. 32:1). However, unlike courtroom indictments elsewhere (Isa. 1; Hos. 4), Micah’s proceedings are unconventional. After declaring that Yahweh will indict Israel, Micah presents a justification of Yahweh rather than a critique of Israel. It is possible to link the resumptive “Listen” (lit., “Hear”) of verse 9 with the “Hear” of verse 2, so that a more typical indictment follows in verses 9–16. While it might be tempting to link Micah with everyday court or covenant proceedings based on the language of the first verse, the succeeding verses follow no known pattern.87

What have I done to you? (6:3–5). This expression, far from being a statement for the prosecution, is found as a pleading defense in the Amarna Letters. In these letters the phrase is the weak defense of a petty prince before the mighty Egyptian pharaoh. In Micah, it is as if Yahweh is in the docket facing the accusations of the people.88 The mention of Miriam and Aaron is notable for its rarity outside the Pentateuch, and the reference to Shittim and Gilgal is simply a reference to the early events of the Conquest narrative (Josh. 2:1; 4:19), referring to staging areas on either side of the Jordan. Yahweh reiterates the events of the Exodus and Conquest, in many ways an encapsulation of Israelite religion. Yahweh had both kept the people from harm (Mic. 6:4a, 5a) and provided positive leadership (6:4b, 5b). As in the covenant ceremony in Joshua 24, the implication of these saving acts should be a statement that “we too will serve the Lord, because he is our God” (Josh. 24:18b).

Balaam (6:5). It is notable that eighth century Micah includes a reference to Balaam. In 1967, excavators at Deir ʿAlla in Jordan uncovered a series of broken plaster fragments dated to the early eighth century with more stories of the seer Balaam. In one of the stories, Balaam sees a vision of a worldwide catastrophe and sets out to foil the plot. The Deir ʿAlla texts are fragmentary and have been difficult to place linguistically. While the letter forms and archaeological context of the finds point to an eighth-century date, some have argued that the language points to an earlier dialect. While the Deir ʿAlla stories and the activities of Balaam in Numbers are not similar in broad strokes, some of the details are identical, even down to the particular phrases used by the authors. In both Numbers and Deir ʿAlla, for instance, Balaam receives special night visions from the divine.89 Micah’s reference, however, ignores or is unaware of any elements unique to the Deir ʿAlla traditions.

Balaam son of Beor inscription

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

With what shall I come before the Lord? (6:6–8). Micah lists a series of possible sacrifices to bring to God. Some have argued that this list is hyperbolic.90 The reference to “thousands” and “ten thousands,” for instance, is a common idiom for numbers beyond counting (1 Sam. 18:7). However, the sacrifices listed here were all too real to the audience, even in their quantity. The year-old animal was the common requirement for a sacrificial animal in texts of Leviticus and Numbers, representing the ideal. Solomon sacrificed flocks without number as part of the dedication of the temple recorded in 1 Kings 8. Oil was both a sacrifice in itself (Gen. 28:18) and a part of a number of priestly ceremonies recorded in Exodus and Leviticus. Archaeological discoveries at sacred precincts from the Bronze through Iron Ages have found sacred oil to be one of the most significant offerings.91

The most extreme sacrifice, however, was the offering of a child to appease the gods or fulfill a vow.92 Again, this was not mere hyperbole as both Mesha in the ninth century and Ahaz in Micah’s own day had done this very thing, likely in both cases when faced with an extreme military difficulty.93 Micah dismisses all of these practices, with logic similar to that of Samuel in 1 Samuel 15:22–23 (or Deut. 10:12–22). Whatever else the prophet may have said about the particulars of these practices,94 no ritual act could outweigh the injustice described in the second half of the chapter.

Dishonest scales … false scales (6:9–12). As in chapter 2, Micah describes dishonest commerce. In the eighth and seventh century, the number of inscribed weights found in the archaeological record increased considerably, as determining exact weights and measures for commerce became increasingly important.95 In addition, archaeological strata from the eighth and seventh centuries show a marked increase in the amount of Hacksilber, or small fragments of silver jewelry or ingots cut or fused to a standard weight. While payment using silver by weight was not new, its use also expanded in the eighth and seventh centuries.96

Hoard of silver ingots and jewelry from 9th-8th century Shiloh

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

The growth of impersonal exchange networks over large distances, exemplified in the Phoenician expansion (see introduction), greatly increased the need for weights and measures. It should come as no surprise that the legal literature of the ancient Near East is concerned with upholding just weights and measurements. The Instruction of Amenemope, for example, includes two chapters entirely devoted to the upholding of accurate measurements. Several Mesopotamian texts are similarly clear on this point.97 Micah does not have to look far to find examples of gross injustices that do not meet even the ethical standards of surrounding groups (Lev. 19:35–36; Ezek. 45:10; Hos. 12:7; Amos 8:5).

I have begun to destroy you (6:13–16). As a judgment for their unjust ways, Micah pronounces a series of curses, often called “futility curses,” for the inverse cause and effect that characterize them (Hos. 4:10, Zeph. 1:13). This is a common curse form found throughout the length and breadth of ancient Near Eastern texts from myths to land grants to vassal treaties.98 These are particularly appropriate in Micah because they specifically refer to exactly the olive oil and wine that were in such demand by the Phoenician traders of the day, just those goods that were being stolen with the unjust weight.

Statutes of Omri (6:16). The meaning of “statues of Omri” is not clear from other biblical texts since Omri is passed over with almost no comment by the author of Kings. This lack of comment is in stark contrast to the portrayal of Omri in ninth century inscriptions. In the Mesha stela, Omri’s rule over Moab is unchallenged by even the rebellious Moabite king, and in the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, Omri’s name is as famous in the northern kingdom of Israel as David’s was in the southern kingdom of Judah.99

Micah’s reference to Omri is juxtaposed with a reference to the works of the house of Ahab. While Ahab receives much more scrutiny in Kings, the Deuteronomist accuses him of so many evils that it is difficult to pick out one in particular. Several suggestions have been made, including idolatry and foreign alliances.100 It is notable that both Omri and Ahab participate in the very thing that Micah condemns in chapter 2. Both of them purchase land from the ancestral owner to create or expand their capital cities (1 Kings 16:24; 21). Given Micah’s obvious aversion to land grabs in general and Samaria in particular, this is another plausible candidate for this sin.101

What misery … (7:1). Micah describes a time at the end of the dry season (near the end of October). The Gezer Calendar, an ancient text describing the agriculture of the Iron Age, describes September and early October as the months of “ingathering,” and late October through early December as the months of “sowing.”102 During September and early October, the summer fruits, grapes, figs, pomegranates, and finally olives were harvested. It was a time of work but also of celebration for the productive harvest (Deut. 16:13–15). But Micah describes the time after the celebration has finished and before the appearance of the “early rains” (Joel 2:23) necessary for the “sowing” of new grains. In this interlude, nothing is growing, nothing is ripening, and one simply hopes through the dryness for rain.103 Perhaps Micah’s metaphor is particularly appropriate as a condemnation of injustice since it is exactly this harsh treatment of the poor, not leaving anything for the gleaner, that was the danger of the increasingly commercial eighth century.

The ruler demands gifts, the judge accepts bribes (7:3). It is the height of injustice when those whose sole task is to be just arbiters are now subject to bribes. The administration of justice defined the Israelite judge and king (Deut 1:17; for the ideal prince see 2 Sam. 8:15, 1 Kings 3:28), but this idea was hardly unique to the Israelites. The Eloquent Peasant expects the Egyptian magistrate to uphold justice and the Egyptian lord to fight corruption as a fundamental moral responsibility.104

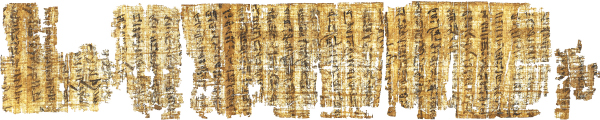

Eloquent Peasant

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Members of his own household (7:5–6). Even the basic family structure falls apart as the “day of punishment” arrives. The groups Micah pairs here describe the spheres of authority within the Israelite family. The father had authority over his sons and the men of his household. The mother had authority over her unmarried daughters and married daughters-in-law. In this sphere the authority of the father or mother was virtually unlimited, and to oppose such authority was a serious offense.105 This image likely combines both rebellion as a tragic corollary of the day of punishment and rebellion as the natural reaction to injustice of the parents by children waiting for the Lord (Matt. 10; Luke 12).

Mire in the streets (7:10). In the ancient town or city, the dirt streets and alleys were the dumping ground for household refuse, often including human excrement.106 This same “mire” could be found when an abandoned cistern was used as a garbage dump (Ps. 40:3; Jer. 38:7). The resulting concoction was not particularly hygienic, and it served as a vivid metaphor for the destination of Micah’s mocker.

Day for building your walls (7:11). This does not refer to the fortification of a city, but rather to the reapportioning of the inheritance of the people. The “walls” in this case are the small boundary walls, often at the edges of fields or vineyards, that marked out one plot from another (Num. 22:14; Ps. 80:2; Isa. 5:5; Hos. 2:6).107 Micah is once again picturing a peaceful agrarian future (see Mic. 4:1–5).

Terracing north of Hebron

Copyright 1995–2009 Phoenix Data Systems

Bashan and Gilead (7:14). Located in the northern Transjordan, Bashan and Gilead had enough rainfall so that plentiful harvests were the norm. Their mere mention brought to mind abundance and fertility in the land since these areas failed to produce only if the famine was complete (Isa. 33:9). Elijah was one who took refuge in this area when famine covered the land (1 Kings 17), but Micah looks farther back and recalls the reaction of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh to this ideal pastureland in Numbers 32.108

Who is a God like you? (7:18–20). In conclusion, Micah returns to the Divine Warrior metaphor of the beginning of the book (1:3). It is at first an odd way to answer the question of verse 18. After all, other gods were pictured as divine warriors. In the Baal Cycle, Anat wades through her enemies much as Yahweh tramps around in this passage, and, in the same cycle, Baal defeats the sea with its depths.109 Since these activities were common divine traits throughout the Near East, the reader might answer that there are many gods like Yahweh.

But this section recalls Exodus 15 and 34, where Yahweh shows his unique love for Israel, redeeming them from oppression and making them his own.110 And it rests in the hope that the victorious Divine Warrior is not out to vanquish merely another human or divine foe as in the Baal Cycle, but that his mighty acts of redemption in the past and judgment in the present point to a future in which he will ultimately be faithful to vanquish iniquity and bless his chosen people.

Bibliography

Andersen, F. I., and D. N. Freedman. Micah. New York: Doubleday, 2000. The best technical commentary on Micah; a working knowledge of Biblical Hebrew is assumed.

King, P. Amos, Hosea, Micah–An Archaeological Commentary. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1988. Insight into the daily lives of the eighth-century prophets.

King, P., and L. E. Stager. Life in Biblical Israel. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001. An essential primer on the cultural context of the ancient biblical writers.

Shaw, Charles S. The Speeches of Micah: A Rhetorical-Historical Analysis. JSOTSup 145. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993. A provocative attempt to understand the historical background of Micah.

Wolff, H. W. Micah the Prophet. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1978. A commentary that focuses on Micah’s social and economic context.

Zevit, Ziony. The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. New York: Continuum, 2001. A current and comprehensive summary of ancient Israelite religion.

Chapter Notes

Main Text Notes

1. P. House, The Unity of the Twelve (JSOTSup 97; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990); idem, “Endings as New Beginnings: Returning to the Lord, the Day of the Lord, and Renewal in the Book of the Twelve,” in Thematic Threads in the Book of the Twelve, ed. P. L. Redditt and A. Schart (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003).

2. C. S. Shaw, The Speeches of Micah: A Rhetorical-Historical Analysis (JSOTSup 145; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), 224.

3. Shaw (ibid., 64, 123–24) argues that Jer. 26 confuses the prophecy of Mic. 3 with the actions of Isa. 37–38 and should be dated to the days of Ahaz; Andersen and Freedman propose a more satisfactory solution to this problem by noting the possibility that this oracle was composed in an earlier time but retold to Hezekiah (F. I. Andersen and D. N. Freedman, Micah [AB; New York: Doubleday, 2000], 113).

4. D. R. Hillers, Micah (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984), 5.

5. M. Cogan and H. Tadmor, II Kings (AB; New York: Doubleday, 1988), 260–63.

6. J. A. Blakely and J. W. Hardin, “Southwestern Judah in the Late Eighth Century B.C.E.,” BASOR 326 (2002): 52–53; D. M. Master, “Trade and Politics: Ashkelon’s Balancing Act in the Seventh Century B.C.E.,” BASOR 330 (2003): 49.

7. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 24–26, 115–17.

8. A. Alt, Kleine Schriften zur Geschichte des Volkes Israel (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1959), 3:373–80; J. L. Mays, Micah (OTL; Philadelphia: Westminster, 1976), 19, 62; H. W. Wolff, Micah the Prophet (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1978), 17–25.

9. Halpern sees the loss of the power of the traditional hinterland as a decisive shift in Israelite religion. B. Halpern, “Jerusalem and the Lineages of the Seventh Century B.C.E.: Kinship and the Rise of Individual Moral Liability,” in Law and Ideology in Monarchic Israel, ed. B. Halpern and D. W. Hobson (JSOTSup 124; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1991), 11–107.

10. S. Gitin, “The Neo-Assyrian Empire and Its Western Periphery: The Levant, with a Focus on Philistine Ekron,” in Assyria 1995, ed. S. Parpola and R. M. Whiting (Helsinki: The Project, 1997), 83–85.

11. Master, “Trade and Politics,” 58–61; R. Ballard et al., “Iron Age Shipwrecks in Deep Water off Ashkelon, Israel,” AJA 106 (2002): 165–66.

12. For a summary of the links between biblical sites and modern tells, the best source is still Y. Aharoni, The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1979); for a summary of the excavation of the ancient sites, see Ephraim Stern, ed., New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1992).

13. A. Abu-Asaf, Der Tempe von ʿAin Dara (Damaszener Forschungen 3; Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1990), 3:12.

14. R. Clifford, The Cosmic Mountain in Canaan and the Old Testament (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1972), 94.

15. Mays, Micah, 42–44; COS, 2:262–63.

16. COS, 2:173.

17. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 170.

18. J. W. Crowfoot, K. M. Kenyon, and E. L. Sukenik, The Buildings of Samaria (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1966), 94–115.

19. J. D. Schloen, The House of the Father as Fact and Symbol (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2001), 155–65.

20. R. Tappy, The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2001), 2:560–79.

21. COS, 2:152.

22. Mays, Micah, 46–48; see Gen. 38 for a discussion of cultic prostitution.

23. Ibid., 54; Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 192.

24. Mays, Micah, 55.

25. P. King and L. E. Stager, Life in Biblical Israel (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 120–21.

26. Ibid., 204–6; COS, 2:303.

27. P. Hanson, The Dawn of Apocalyptic (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1975), 375.

28. COS, 2:297.

29. Mays, Micah, 5.

30. See summary in Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 208–9.

31. A. F. Rainey, “Toponymics of Eretz-Israel,” BASOR 231 (1978): 10.

32. B. Waltke, “Micah,” in The Minor Prophets, ed. T. E. McComisky (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1993), 628–29.

33. Shaw, The Speeches of Micah, 35.

34. W. G. Dever, “Khirbet el Qôm,” NEAEHL, 1233.

35. See summary in Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 209; also T. McComiskey, “Micah,” Expositor’s Bible Commentary, ed. F. Gaebelein (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1985), 407–8.

36. Mays, Micah, 56.

37. C. S. Shaw, “Micah 1:10–16 Reconsidered,” JBL 106 (1987): 225.

38. D. Ussishkin, “Lachish,” NEAEHL, 905–9; idem, The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib (Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, 1982).

39. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 242–45.

40. See Andersen and Freedman, Micah, for a summary of the historical geography, and NEAEHL for an archaeological summary.

41. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 372–73.

42. L. E. Stager, “The Archaeology of the Family in Ancient Israel,” BASOR 260 (1985): 20–22.

43. Alt, Kleine Schriften, 373–81, or more recently with a slightly different emphasis, T. Green, “Class Differentiation and Power(lessness) in Eighth-Century B.C.E. Israel and Judah” (Ph.D. diss., Vanderbilt University, 1997), 2:512–28.

44. Shaw, The Speeches of Micah, 84–87.

45. J. H. Walton, V. Matthews, and M. Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 782–83.

46. Mays, Micah, 66; Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 289–90.

47. A. Malamat, Mari and the Bible (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 61, 86.

48. This is not universally agreed upon. See E. Ben Zvi, “Micah,” in The Jewish Study Bible, ed. A. Berlin and M. Z. Brettler (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004), 1210.

49. Mays, Micah, 75; M. R. Jacobs, The Conceptual Coherence of the Book of Micah (JSOTSup 322; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), 116–17.

50. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 343; Shaw, The Speeches of Micah, 75–78; Waltke, “Micah,” 640–41.

51. Ø. S. Labianca and R. W. Younker, “The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (ca. 1400–500 B.C.E.),” in The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, ed. T. Levy (New York: Facts on File, 1995), 408.

52. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 361–64.

53. Malamat, Mari, 69, 89.

54. Mays, Micah, 84.

55. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 413–27.

56. Clifford, The Cosmic Mountain, 57, 79.

57. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 93–107.

58. Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961), 166.

59. Mays, Micah, 99

60. Y. Shiloh, City of David I (Qedem 19; Jerusalem: Hebrew Univ. Press, 1984), 27.

61. Ibid., 27; Jane Cahill, “Jerusalem in David and Solomon’s Time,” BAR 30.6 (2004): 25; contra D. Bahat, The Illustrated Atlas of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Carta, 1989), 26.

62. Cogan and Tadmor, II Kings, 260–61.

63. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 454.

64. Mays, Micah, 115; While some have pointed to “striking on the check” in both the code of Hammurabi and the Mesopotamian Akitu festival, these parallels are not relevant here (contra Walton, Matthews, and Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament, 784).

65. D. M. Master, “State Formation Theory and the Kingdom of Israel,” JNES 60 (2001): 130–31; Schloen, House of the Father, 151–64.

66. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 240–41.

67. For “Ephrata” in the clans of Judah, see Sara Japhet, I & II Chronicles (OTL; Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1993), 65–90.

68. COS, 2:420, particularly n. 11; COS, 1:97.

69. COS, 2:180; Z. Zevit, The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches (New York: Continuum, 2001), 405–35.

70. F. M. Cross, “The Cave Inscription from Khirbet Beit Lei,” Near Eastern Archaeology in the Twentieth Century: Essays in Honor of Nelson Glueck, ed. J. A. Sanders (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970), 299–306.

71. For an eschatological reading, see Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 479–81; for a metaphorical reading, see T. E. McComiskey, “Micah,” 429.

72. K. J. Cathcart, “Notes on Micah 5:4–5,” Bib 49 (1968): 511–14; idem, “Micah 5:4–5 and Semitic Incantations,” Bib 59 (1978): 38–48; F. Saracino, “A State of Siege: Mi 5:4–5 and an Ugaritic Prayer,” ZAW 95 (1983): 263–66.

73. Mays, Micah, 121; or perhaps just emphasizing that the remnant, like the dew, comes from God and as such, as the lion, is unstoppable, H. W. Wolff, Micah (Augsburg: Fortress, 1990), 156–57.

74. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 485–87.

75. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 242–45.

76. Shiloh, “Megiddo,” NEAEHL, 1020–21.

77. Ussishkin, Conquest of Lachish, 27–48.

78. Zevit, Religions of Ancient Israel, 578 n. 237; see 81–479 for much more detail on these practices.

79. H. J. Franken and M. L. Steiner, Excavations in Jerusalem 1961–1967 (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990), 2:125–29.

80. Kenyon, Digging up Jerusalem (New York: Praeger, 1974), 142.

81. Zevit, Religions of Ancient Israel, 256–62.

82. COS, 1:299–301.

83. J. A. Hadley, “Yahweh and his ‘Asherah’: Archaeology and Textual Evidence for the Cult of the Goddess,” in Ein Gott allein? ed. W. Dietrich and M. A. Klopfenstein (Freiburg: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1994), 235–37.

84. McCarter’s translation, likely because of the possessive (“his”), which is never used of a person or God in the biblical text, would argue that this is merely cultic paraphernalia (COS, 2:179).

85. COS, 2:171–72.

86. K. Jeppesen, “Micah V 12 in the Light of a Recent Archaeological Discovery,” VT 34 (1984): 462–66. Others, however, just view this pairing as summative of the military and cultic crutches that Micah is condemning in 5:10–15 (see Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 489).

87. deVaux, Ancient Israel, 156; Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 507–11.

88. COS, 3:237.

89. COS, 2:142; J. A. Hackett, “Deir ʿAlla Texts,” ABD, 2:129–30.

90. Walton, Matthews, and Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament, 786.

91. L. E. Stager and S. Wolff, “Production and Commerce in Temple Courtyards: An Olive Press in the Sacred Precinct at Tel Dan,” BASOR 243 (1981): 95–102.

92. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 362.

93. For summary and bibliography, see Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 532–39.

94. For a fuller discussion, see J. Levenson, The Death and Life of the Beloved Son (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 1993), although we would agree with deVaux against Levenson’s interpretation of child sacrifice as an early Yahwistic practice. See R. deVaux, Studies in Old Testament Sacrifice (Cardiff: University of Wales, 1971).

95. Note Kletter’s caveats about our poor understanding of the Iron IIA weight system. R. Kletter, Economic Keystones: The Weight System of the Kingdom of Judah (JSOTSup 276; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 132–37.

96. S. Gitin and A. Golani, “The Tel Miqne-Ekron Silver Hoards: The Assyrian and Phoenician Connections,” in Hacksilber to Coinage: New Insights in the Monetary History of the Near East and Greece, ed. M. S. Balmuth (New York: American Numismatic Society, 2001), 37–40.

97. COS, 1:119–20; Walton, Matthews, and Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament, 786.

98. D. R. Hillers, Treaty-Curses and the Old Testament Prophets (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1964); W. M. de Bruin, “Vergeefse Moeite als Oordeel van God. Een onderzoek naar de ‘Wirkungslosigkeitssprüche’ in het Oude Testament” (Ph.D. diss., Utrecht University, 1997).

99. COS, 2:270; also 2:137.

100. Walton, Matthews, and Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament, 786; Shaw, The Speeches of Micah, 179.

101. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 550.

102. COS, 2:222.

103. O. Borowski, Agriculture in Iron Age Israel (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1987), 34, 37, 41.

104. COS, 1:98–99, 101.

105. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 36–40; C. Meyers, “Having Their Space and Eating There Too: Bread Production and Female Power in Ancient Israelite Households,” Nashim 5 (2002): 28–33.

106. King and Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, 70.

107. P. King, Amos, Hosea, Micah–An Archaeological Commentary (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1988), 72.

108. G. A. Smith, The Twelve Minor Prophets (New York: George H. Doran, 1929), 1:386–97.

109. COS, 1:248–50; Walton, Matthews, and Chavalas, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament, 787.

110. Andersen and Freedman, Micah, 597–99.