Zechariah

by Kenneth G. Hoglund and John H. Walton

Temple Building Stele of Ur-Nammu

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY

Introduction

Like his contemporary Haggai, Zechariah finds himself called to challenge the postexilic community to complete the rebuilding of the temple. While the first members of the community returned to Jerusalem around 538 B.C., the opening chapters of Ezra suggest they were so preoccupied by the task of rebuilding the city they could not complete the temple. Only because of the subsequent efforts of Zerubbabel, the governor of the province, and the ministries of Haggai and Zechariah, is the temple finished around 515 B.C. (Ezra 5:1; 6:15).

The leadership of the community was responsible for securing the arrangements for temple building as illustrated by this statue of Gudea, governor of Lagash, who has the plan for the temple on his lap.

Christina Beblavi, courtesy of the Louvre

Although the archaeological data are fragmentary, enough information exists to suggest that the exiles returned to a shattered urban landscape where considerable effort was needed simply to maintain survival. Modern-day population estimates place the population in the Persian period around 30,000 individuals in the area of the province of Yehud (the Persian administrative name for the district), which represents a loss of 70 percent of the population of the region prior to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. Jerusalem was the only significant city in the province, and much of the population lived in small, unwalled villages.1 This picture is consistent with the tone of the prophetic messages of Haggai and Zechariah; the community was struggling to rebuild a sustainable economy, and severe limits on resources made rebuilding the temple an almost unthinkable task.2 For this reason, both prophets must remind their audiences that God controls the resources (see Hag. 2:8–9; Zech. 4:6–7).

The literary form of the book falls into three distinct parts. The first part (chs. 1–8) contains a series of eight visions Zechariah receives, artfully arranged in a balanced structure that places the vision of Joshua’s installation as high priest (3:1–10) and the vision of the golden lampstand (4:1–14) at the center. These eight visions are followed by more conventional prophetic pronouncements on the need for social justice and the promise of the divine restoration of Jerusalem. Chapters 9–11 opens with the title “An Oracle” and launches into a prolonged metaphor on God’s concern for proper leadership of the community. The final section (chs. 12–14) also opens with the title “An Oracle” and seems to deal with a battle over Jerusalem, reestablishing the centrality of the city as the place for God’s holiness to dwell.3

Persian dualism featured the good Ahuramazda balanced with the evil Ahriman (Angra Mainyu). On the right, Ahuramazda astride his horse tramples Ahriman while he delivers a diadem to the king at his investitutre.

Ginolerhino

One emphasis that ties the sections together is the urgency of rebuilding the temple and the implications for completing the task. In weaving his various points around this emphasis, the prophet taps into common motifs and metaphors from temple-building accounts in the ancient Near East.4 A brief summary of one typical narrative can illustrate some of these. The Sippar Cylinder of Nabonidus (556–539 B.C.) commemorates the rebuilding of one of the primary temples to the god Sin located in Harran. The account notes, “Ehulhul, the temple of Sin in Harran, where since the days of yore Sin, the great lord, had established his favorite residence–his heart became angry against that city and temple….”5 The account continues that Sin sent the Medes to destroy the city and the temple, but then becomes “reconciled” with the city. To honor Nabonidus Sin appears to him in a dream with Marduk, the primary god of Babylon, to command the rebuilding of the temple.

When Nabonidus indicates his concern because the city is under control of the Medes, Marduk declares the threat will be no more. Both deities call forth Cyrus of Persia to defeat the Medes and allow Nabonidus to enter the city. So Nabonidus undertakes the rebuilding “in a propitious month, on an auspicious day” that divination, probably liver omens, revealed. The temple is completed and Nabonidus brings images of various deities from Babylon to Harran “in joy and gladness,” filling the temple with fine gifts and causing Harran to appear “as brilliant as moonlight” (Sin being associated with the Moon). Following the completion of this work, the king prays to Sin to bless the city and temple and to support Nabonidus’s reign by conquering the king’s enemies and annihilating anyone hostile to the king.6

One can see how the opening of Zechariah’s work recalls God’s earlier displeasure with the community, only to move on to the first vision in which God’s intention is to see the temple rebuilt. Subsequent visions underscore God’s establishing the political conditions for the temple to be completed and calls on the community’s leadership to recognize their roles. The concluding visions offer the promise of purification and universal peace and prosperity. All along, the conditions that led to God’s initial anger with the community are warned against, and the first section closes with the image of the community’s maintaining its uniqueness through obedience.

The second section continues with the universal rule of God and God’s intention to encamp at the temple and serve as the community’s powerful defender. As part of this role, God pledges to destroy the bad shepherds. The third section can be seen as God’s efforts to annihilate all the enemies of the community, and chapter 14 seems to end in an idyllic world of peace and prosperity as a result of God’s presence in the temple.

One difference between typical temple-rebuilding texts and the prophet’s message is the focus of the divine attention. While Sin and Marduk bestow favors and support to Nabonidus the king, in Zechariah God’s concerns are for the community at large. The community, having seen the complete loss of political self-determination and now very conscious of their servitude under an imperial system and a king not of their choosing, may have given up all aspirations for a king of their own. But the prophet powerfully reminds them God can work directly for their behalf and that Jerusalem, not the king, is particularly favored.

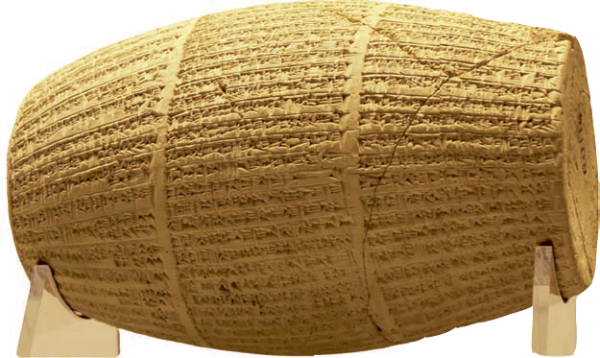

Sippar Cylinder of Nabonidus

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

The oracles of Zechariah sometimes have been termed “early apocalyptic” or “proto-apocalyptic,” largely because elements within the oracles appear in other apocalyptic literature, such as Daniel or Revelation. Others have denied any apocalyptic influence in the book. Often what is more at stake is the definitions different scholars use to characterize when a work is “apocalyptic.”7 Many scholars agree that one of the central themes in apocalyptic literature is a conflict involving the whole world in which the outcome is uncertain until God, or God and the faithful, prevail.

Some argue this idea of an ultimate battle between good and evil has been borrowed from Persian religion, where a dualistic understanding of the universe may have been the norm. The only extant Persian religious literature is many centuries later than the Persian empire, and how far back in time these ideas go is a matter of debate among specialists.8 At least in this later expression, the world is dominated by a set of divine twins: one morally good, the other morally evil. These deities are balanced in powers, and the ultimate end of the world is in question until one of them is able to gain advantage over the other.9 Certainly in Zechariah’s vision of God’s encounter with Satan (3:1–3) there is no question of God’s supremacy over evil. However, the conflict portrayed in chapter 14 may veer closer to what might be called “apocalyptic.”

Unlike Haggai, the prophet Zechariah focuses on the political structures of the early postexilic period, particularly on the roles of the governor and high priest. While often filled with hope for the future, there are places where the leadership is chastised and there is the promise of God’s judgment against worthless leadership. The prophet also uses more symbolic language than Haggai as he underscores God’s continual care and concern for Judah and Jerusalem.