Malachi

by Andrew E. Hill

Winged disk in Assyria symbolized Shamash, the sun god.

Caryn Reeder, courtesy of the British Museum

Introduction

Historical Setting

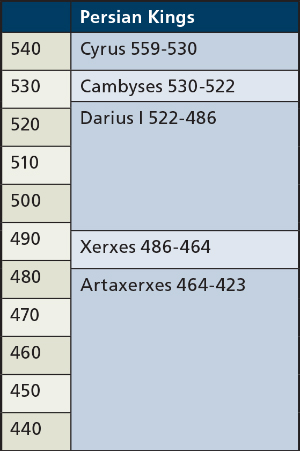

Unlike Haggai and Zechariah, the book of Malachi contains no date formulas linking the prophet’s message to the reign of any Persian king. Malachi does make reference to the governor of Yehud (1:8) and a rebuilt temple in Jerusalem (1:10). Thus the book may be dated broadly to the period after the completion of the Second Temple (515 B.C.). A careful study of the language of the prophet’s oracles reveals that the book has a great affinity to Haggai and Zechariah, suggesting a terminus ad quem of the reforms of Ezra and (later Nehemiah) initiated in Jerusalem, beginning in 458 (cf. Ezra 7:8).1

It seems likely that Malachi addresses the Jews in the province of Yehud during the reign of King Darius I (522–486 B.C.), making him a slightly later contemporary of these two prophets of Yahweh’s Second Temple. It is even possible that the battle between the Persians and Greeks at Marathon (ca. 490) was the occasion prompting Malachi’s message. The prophet may have interpreted the titanic struggle between East and West as at least a partial fulfillment of Haggai’s prediction that God was about “to shake the heavens and the earth” and “overturn royal thrones” (Hag. 2:21–22).

Literary Setting

The discourse units in Malachi may be broadly categorized as judgment speeches since they accuse, indict, and pronounce judgment on his audience. More precisely, the literary form of these oracles may be linked to Westermann’s legal-procedure (or trial speech) and the disputation.2 The disputation speech pits the prophet of God against his audience in adversarial dialogue (whether real or hypothetical). Typically in Malachi the disputation features these elements:

• a truth claim declared by the prophet

• a hypothetical refutation on the part of the audience in the form of a question

• the prophet’s answer to the audience rebuttal by restating his initial premise

• the presentation of additional supporting evidence

Westermann roots the prophetic disputation in the literary form of the psalmic lament.3 Others identify affinities between the prophetic disputation and the diatribe of pedagogical discourse in the schools associated with the wisdom tradition of the ancient world.4 Brueggemann correctly isolates the rhetorical question as the literary and pedagogical bridge between prophecy and wisdom because such instruction is both dialogical and dialectical.5 The rhetorical question is a prominent feature in the sermons of Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi and makes the prophetic speech of these postexilic prophets a rather distinct genre in the literature of the biblical world.6