Malachi’s Second Disputation: Faithless Priests Rebuked (1:6–2:9)

Sacrifice crippled or diseased animals (1:8). The prophet rebukes the people and the priests for shaming Yahweh with inferior offerings that were considered inappropriate even for the local Persian-appointed governor. The termination of temple funding from the Persian government may have prompted such behavior as a “cost-cutting” measure (see 3:8 below),14 but it seems more likely that the burden of cultic and imperial taxation became so heavy that compromising the temple sacrificial rituals and ignoring the tithe requirements was a pragmatic solution for maintaining the barest standards of subsistence living in the face of persistent economic depression as a result of drought and blight (cf. Hag. 1:6, 10–11; Zech. 8:12; Mal. 3:14).15

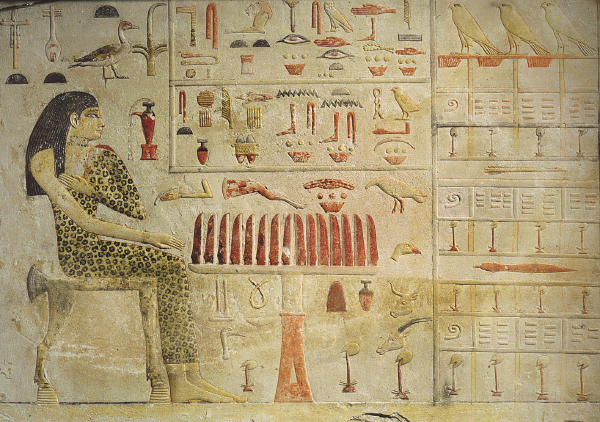

The Lord’s table (1:12). This expression is unique to Malachi in the OT. The context of the passage suggests the table is synonymous with the altar of burnt offering since animal and grain sacrifices were figuratively understood as “food” for Yahweh (cf. 1:7; Lev. 3:11, 16). The “table” was also a symbol of fellowship in the ancient world since the meal or “feast” was a part of the covenant ratification ceremony, the sealing of an alliance with a ceremonial meal.16 The prophet rebukes the people and the priests because the offering of impure sacrifices profaned the worship of Yahweh and demonstrated contempt for their covenant relationship with him.

Priestess with table filled with offerings

Werner Forman Archive/The Louvre

Malachi’s Third Disputation: Faithless People Rebuked (2:10–16)

Marrying the daughter of a foreign god (2:11). This difficult expression is used in the collective sense of foreign women who married into the Hebrew clans of Yehud (in violation of the Israelite practice of endogamy or marrying within the ethnic group, cf. Deut. 7:3–4). The prophet recognized that in intermarriage of this sort, one weds both a foreign woman and a foreign god. The gravity of the situation accounts for Malachi’s unusual language in the larger disputation, insinuating that the “adultery” of divorce from Hebrew women and remarriage to foreign women was tantamount to “idolatry” (cf. Mal. 2:14–16). The practice of deserting and divorcing Hebrew women for the purpose of marrying non-Hebrew women was probably motivated by economics, since intermarriage was a requisite for entering the well-established mercantile guilds of postexilic Palestine already in place when the Jews returned from exile.17

Marriage … divorce (2:14–16). Mosaic law permitted a man to divorce his wife for “indecency” of an unspecified nature (Deut. 24:1–4; presumably misconduct short of adultery, since that was a capital offense, Lev. 20:10; cf. Matt. 19:7–9).18 Malachi’s enlightened view of marriage and harsh admonition against divorce apparently had little impact on the postexilic community as evidenced by the “reforms” undertaken by Ezra and Nehemiah when they confronted the same abuses some five decades later (cf. Neh. 13:23–27).

Documents from Elephantine, a sectarian Jewish military colony located near Aswan in Egypt, sheds light on Jewish marriage and divorce practices in the Persian period. Unlike Malachi’s understanding of marriage as a covenant (2:14), the Elephantine community emphasized the contractual nature of marriage with attention given to the pragmatic legal and economic aspects of the marriage bond (e.g., issues of bride-price, dowry, property rights, and inheritance). The union resulting from the marriage contract could be dissolved by either party at will and without delineating any specific grounds for divorce. The marriage and divorce practices at Elephantine are precursors of a more lax stance on the customs in later Judaism, in stark contrast to Malachi’s teaching.19

Malachi’s Fourth Disputation: Judgment and Purification (2:17–3:5)

Messenger (3:1). The idea of a forerunner preparing the way of the Lord also occurs in Isaiah 40:3. The messenger often served as a herald in the ancient world by delivering an oral message to another party, giving military or political news of some sort (whether good or bad), or announcing significant events. Typically the messenger was selected and commissioned in council by an authority figure, either royal or divine.20 The messenger as a representative of the authority figure was charged to speak only the message he had received.

The announcement of a visitation by a dignitary demanded preparation on the part of the people in keeping with the customs of hospitality and the obligation of loyalty to the overlord. Such preparation may also have involved making ready a processional highway for the dignitary more literally in terms of clearing and repairing the roads leading to the destination, so that the royal entourage, including the servants carrying the king’s palanquin, were not at risk of stumbling (Song 3:7–9; cf. the report of the oxen stumbling while hauling the cart transporting the ark of the covenant, 2 Sam. 6:6).

Refiner’s fire (3:2). Malachi borrows this imagery of God’s refining his people Israel by burning or smelting away the dross of their evil ways from Isaiah (Isa. 1:25), Jeremiah (Jer. 6:29; 9:7), and Ezekiel (Ezek. 22:17–22). There is a shift in the use of the metal-refining motif from the destructive aspects of divine judgment in preexilic prophecy to a stress on purification in the postexilic prophets (cf. Zech. 13:1, 9).21

Metalworkers from the tomb of Mereruka

Werner Forman Archive

The refining and smelting of metals was accomplished in one of two types of furnaces: either the kiln or “blast furnace,” in which there is direct contact between the fuel and the ore yielding an oxidizing or reducing reaction, or the “crucible furnace,” which protects the ore or metal from direct contact with fuel of the fire or the products of its combustion and achieves separation of precious metals by means of both oxidation and amalgamation.22 Malachi may be referring to a metallurgy process known as cupellation. Such refinement of silver required exposure of the ores to high temperatures in a blast of the air (from a bellows), resulting in the oxidation of unwanted metals and other impurities. The purified silver was retrieved in a cupel or a small cup-like mold made of a porous material like bone ash or clay.23

Launderer’s soap (3:2). This term (Heb. bōrît) occurs in the OT only here and in Jeremiah 2:22. The word describes an alkaline salt or soda powder derived from the iceplant (found in Mesopotamia but not Syro-Palestine) and used as a laundry detergent in the ancient world. Most scholars understand that Malachi appeals to the imagery of two common trades, the smelter and the fuller or launderer, to demonstrate the pattern of divine judgment as both testing and cleansing (cf. Ps. 66:10; Dan. 11:35; 12:10). Others interpret the expression against the backdrop of smelting metals since lye or potash may be used as a reagent in separating the dross from the precious metal.24 If so, then the prophet makes reference to a two-stage metallurgy process of smelting and purifying the crude lead.

Sorcerers (3:5). The term refers to those who practice divination or fortune-telling by means of occult magic and witchcraft to influence people or events for personal gain or that of their clients.25 Sorcery was among the list of Canaanite customs prohibited for the Hebrews by the Mosaic law (Deut. 18:10); violators were subject to the penalty of banishment (or premature death by some divine act[?], Lev. 20:6). The practice of sorcery persisted in postexilic Yehud from preexilic times (cf. Isa. 47:9; Mic. 5:12).

Ritual series Shurpu contains incantations to purify someone from the influence of evil.

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Mesopotamian and Anatolian cultures understood magic as “a reasoned system of techniques for influencing the gods and other supernatural powers that can be taught and learned…. Magic not only manipulates occult forces but also endeavors to master the higher supernatural powers with which religion is concerned.”26 The lines between magic and religion blurred for the ancients, although the malicious practice of magic (e.g., witchery or sorcery) was distinguished from “defensive” magic performed by legitimate practitioners (e.g., exorcists).27 This malicious witchcraft or black magic was also a taboo punishable by death in some instances according to ancient Near Eastern law codes, including the Laws of Hammurapi (§ 2), the Middle Assyrian Laws (A 47), and Hittite Laws (44b, 111, 163, 170).28