June 28, 1914. Police subdue accomplices of Gavrilo Princip, who has just killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Austrian heir apparent, igniting a war in which nearly 15 million soldiers and civilians will die. akg-images

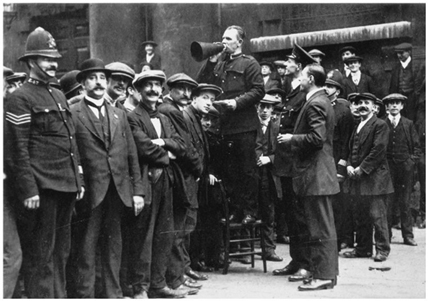

Britons flock to enlist in Trafalgar Square. Lord Kitchener’s 1914 call for 100,000 volunteers was topped fivefold in one month by men expecting a swift, glorious adventure. Some 700,000 Tommies would never return. Imperial War Museum, London

Adolf Hitler in a crowd welcoming the war. No major conflict had occurred on the European continent for nearly forty-five years and the belligerents anticipated quick victory. Imperial War Museum, London

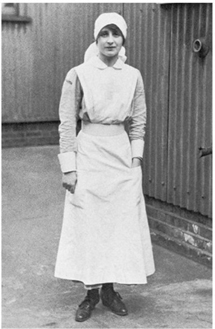

Vera Brittain, a volunteer British nurse in a war that was to take the lives of her brother, her fiancé, and two close friends. She later wrote Testament of Youth, a searing memoir of the experience. William Ready Division, McMaster University Library, Canada

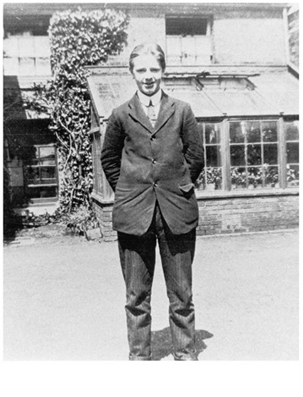

Roland Leighton, Vera Brittain’s fiancé, a prizewinning student who left Oxford to join the 7th Worcestershires. He was killed three days before he was to depart on Christmas leave in 1915. William Ready Division, McMaster University Library, Canada

German and British soldiers gather in no-man’s-land during the spontaneous 1914 Christmas truce, which was regarded by the generals as treasonous but considered a rare sane moment by the troops. Imperial War Museum, London

The 3rd Tyneside Irish advancing on July 1, 1916, the first day of the Somme offensive. More than 19,000 men, young and healthy at 7 A.M., were dead within hours. Field Marshal Douglas Haig declared the casualties not excessive. Imperial War Museum, London

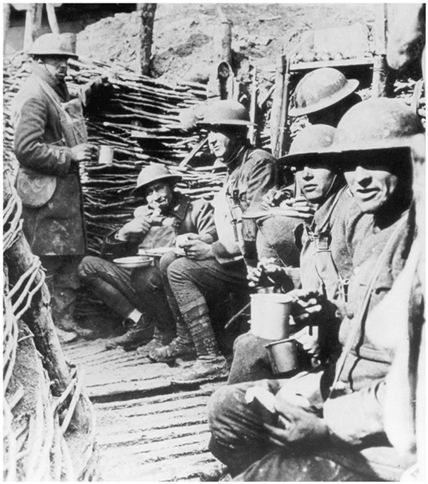

By 1916, thoughts of Christmas truces were long since past. Here British Tommies eat their holiday rations in a shell hole at Beaumont Hamel before the hastily dug grave of a comrade. Imperial War Museum, London

Blinded gas victims. In 1915 the Germans introduced poison gas, developed by Fritz Haber, who had earlier won renown for developing agricultural fertilizers. Gas was unreliable, but cheap and terrifying. Imperial War Museum, London

Australians who fell at the wire near Peronne illustrate the slaughter advancing men faced against the six-hundred-rounds-per-minute firepower of German machine guns. Note the shell burst on the horizon. Imperial War Museum, London

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander of British forces in France. He disparaged not only tanks and planes but even machine guns. A biographer called him a good general “for a man without genius.” U.S. Army Military History Institute

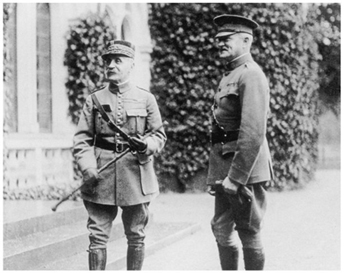

Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch with General John J. Pershing. Foch wanted Pershing’s men as replacements for depleted British and French units. Pershing held out for independent American divisions and won. U.S. Army Military History Institute

The German general staff, led by Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, who projected stolid respectability while his chief of staff, Erich Ludendorff, was the brains and almost led Germany to victory in 1918. American Battle Monuments Commission

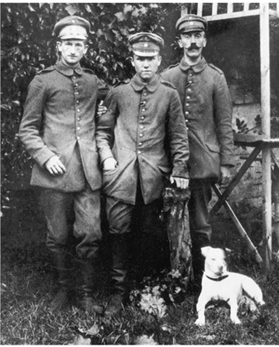

Corporal Hitler (right) welcomed the war, which rescued him from a life of near dereliction. In four years at the front he frequently escaped death and won the Iron Cross, First Class, a rare award for an enlisted man. Ullstein Bilderdienst

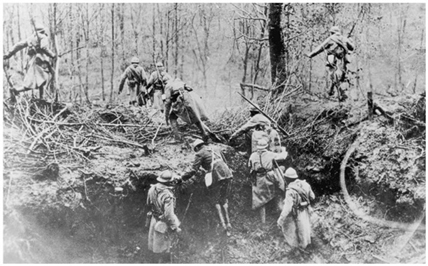

French troops during the 1916 battle of Verdun, a shifting charnel house where one village changed hands thirteen times and 7,000 horses died in one day. One historian judged Verdun the war’s “most senseless episode.” U.S. Army Military History Institute

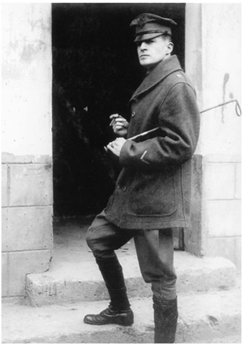

Douglas MacArthur, the youngest general in the American Expeditionary Forces. He personally led raids in flamboyant dress, armed with only a riding crop, and once remarked, “It’s the orders you disobey that make you famous.” National Archives

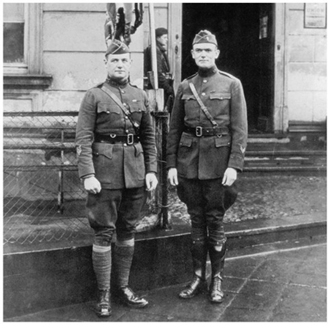

William J. Donovan of the “Fighting 69th” (left) with Chaplain Francis Duffy. Donovan won the Medal of Honor and in World War II became America’s first spy chief as head of the Office of Strategic Services. National Archives

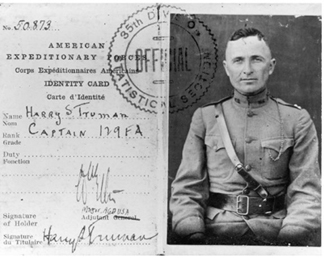

Artillery Captain Harry Truman, whose battery fired until minutes before the war’s end. Truman opposed the armistice as premature, displaying the sternness later evident in his decision to use the atom bomb in World War II. Truman Library

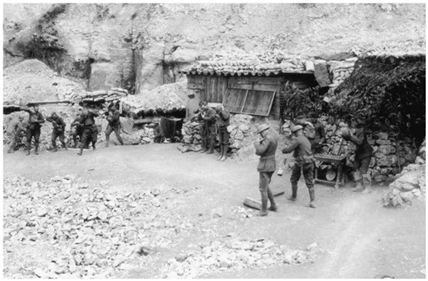

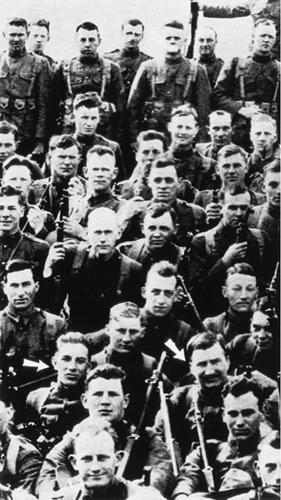

Men of the 167th Infantry Regiment. The number of doughboys in France ultimately approached 2 million and, with French and British troops exhausted after four years of fighting, tipped the scales in favor of Allied victory. U.S. Army Military History Institute

With clanging alert sounded, American soldiers rush to don gas masks. As gas tactics advanced, more men were put out of action by phosgene and mustard than by rifle fire and grenades combined. National Archives

Americans go “over the top.” General Pershing scorned trench stalemate, favoring open warfare. There were 26,000 men killed in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which was then America’s largest loss of life in a single battle. AP/Wide World Photos

Alvin G. York was a corporal in the 82nd Division when he killed 28 Germans and captured 132, exploits for which he received the Medal of Honor and emerged as a World War I legend. U.S. Army Military History Institute

Chaplain Duffy (center) conducts a service over the grave of flier Quentin Roosevelt, youngest son of former president Theodore Roosevelt. One of four brothers in uniform, the pilot was shot down on Bastille Day 1918. U.S. Army Military History Institute

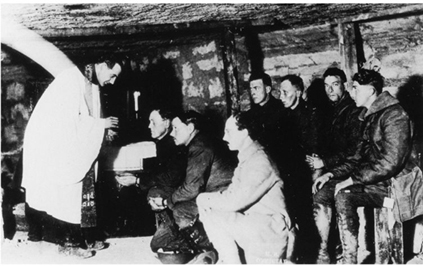

Chaplain Lyman Rollins administers communion to men of the 101st Infantry in a cave near Chemin des Dames. Within the hour, they would be out of the trenches and advancing into enemy fire. U.S. Army Historical Institute

British dead near the war’s end. Their families at least knew the soldiers’ ultimate fate. After the war, a monument was erected at Thiepval containing the names of 73,412 British Empire men, “the Missing of the Somme.” Imperial War Museum, London

Private Henry Gunther (arrow at right), killed at 10:59 A.M. on November 11, was officially the last AEF battle death. Had the fighting stopped during armistice negotiations, some 6,600 lives would likely have been saved. Baltimore Sun

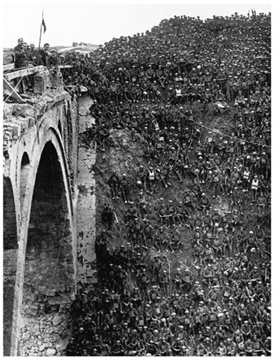

British soldiers of the Staffordshire Territorials carpet a bank of the San Quentin Canal toward the war’s end. Several can be seen holding German helmets. Imperial War Museum, London

After the armistice, General Charles P. Summerall crosses one of the pontoon bridges over the Meuse River over which he sent men during the last morning of the war. The cost: 1,130 casualties, including 127 dead. National Archives

Similar headlines appeared all over America, followed by feverish celebration. However, the war had not ended at 6 A.M., and in the hours before 11 A.M. men were still fighting and dying. New York State Library

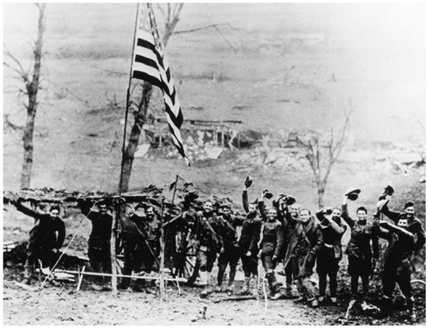

The 105th Field Artillery after firing its last round on Armistice Day. Long ropes were tied to the lanyards of many guns so that hundreds of doughboys could pull them and claim to have fired the last shot of the war. U.S. Army Historical Institute