It was a late August afternoon, and the sun was sending slanting shadows across Union Square in Manhattan. It’s a peculiar kind of day, Jenny thought as she came up from the subway and turned east. This was the last day she needed to go to the apartment of her grandmother, who had died three weeks ago.

She had already cleaned out most of the apartment. The furniture and all of Gran’s household goods, as well as her clothing, would be picked up at five o’clock by the diocese charity.

Her mother and father were both pediatricians in San Francisco and had intensely busy schedules. Having just passed the bar exam after graduating from Stanford Law School, Jenny was free to do the job. Next week, she would be starting as a deputy district attorney in San Francisco.

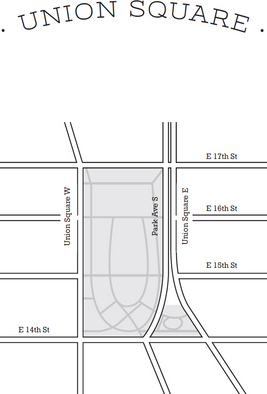

At First Avenue, she looked up while waiting for the light to change. She could see the windows of her grandmother’s apartment on the fourth floor of 415 East Fourteenth Street. Gran had been one of the first tenants to move there in 1949. She and my grandfather moved to New Jersey when Mom was five, Jennie thought, but she moved back after my grandfather died. That was twenty years ago.

Filled with memories of the grandmother she had adored, Jenny didn’t notice when the light turned green. It’s almost as though I’m seeing her in the window, watching for me the way she did when I’d visit her, she reminisced. An impatient pedestrian brushed against her shoulder as he walked around her, and she realized the light was turning green again. She crossed the street and walked the short distance to the entrance of Gran’s building. There, with increasingly reluctant steps, she entered the security code, opened the door, walked to the elevator, got in, and pushed the button.

On the fourth floor, she got off the elevator and slowly walked down the corridor to her grandmother’s apartment. Tears came to her eyes as she thought of the countless times her grandmother had been waiting with the door open after having seen her cross the street. Swallowing the lump in her throat, Jenny turned the key in the lock and opened the door. She reminded herself that, at eighty-six, Gran had been ready to go. She had said that twenty years was a long time without her grandfather, and she wanted to be with him.

And she had started to drift into dementia, talking about someone named Sarah … how Barney didn’t kill her … Vincent did … that someday she’d prove it.

If there’s anything Gran wouldn’t have wanted to live with, it’s dementia, Jenny thought. Taking a deep breath, she looked around the room. The boxes she had packed were clustered together. The bookshelves were bare. The tabletops were empty. Yesterday she had wrapped and packed the Royal Doulton figurines that her grandmother had loved, and the framed family pictures that would be sent to California.

She only had one job left. It was to go through her grandmother’s hope chest to see if there was anything else to keep.

The hope chest was special. She started to walk down the hallway to the small bedroom that Gran had turned into a den. Even though she had a sweater on, she felt chilled. She wondered if all apartments or homes felt like this after the person who had lived in them was gone.

Entering the room, she sat on the convertible couch that had been her bed there ever since she was eleven years old. That was the first time she had been allowed to fly alone from California and spend a month of the summer with her grandmother.

Jenny remembered how her grandmother used to open the chest and always take out a present for her whenever she was visiting. But she had never allowed her granddaughter to rummage through it. “There are some things I don’t want to share, Jenny,” she had said. “Maybe someday I’ll let you look at them. Or a maybe I’ll get rid of them. I don’t know yet.”

I wonder if Gran ever did get rid of whatever it was that was so secret? Jenny asked herself.

The hope chest now served as a coffee table in the den.

She sat on the couch, took a deep breath, and lifted the lid. She soon realized that most of the hope chest was filled with heavy blankets and quilts, the kind that had long since been replaced by lighter comforters.

Why did Gran keep all this stuff? Jenny wondered. Struggling to take the blankets out, she then stacked them into a discard pile on the floor. Maybe someone can use them, she decided. They do look warm.

Next were three linen tablecloth and napkin sets, the kind her grandmother had always joked about. “Almost nobody bothers with linen tablecloths and napkins anymore, unless it’s Thanksgiving or Christmas,” she had said. “It’s a wash-and-dry world.”

When I get married, Gran, I’ll use them in your memory on Thanksgiving and Christmas and special occasions, Jenny promised.

She was almost to the bottom of the trunk. A wedding album with a white leather cover, inscribed with Our Wedding Day in gold lettering, was the next item. Jenny opened it. The pictures were in black and white. The first one was of her grandmother in her wedding gown arriving at the church. Jennie gasped. Gran showed this to me years ago, but I never realized how much I would grow to look like her. They had the same high cheekbones, the same dark hair, the same features. It’s like looking in a mirror, she thought.

She remembered that when Gran had shown her the album, she’d pointed out the people in it. “That was your father’s best friend … That was my maid of honor, your great-aunt … And doesn’t your grandfather look handsome? You were only five when he died, so of course you have no memory of him.”

I do have some vague memories of him, Jenny thought. He would hug me and give me a big kiss and then recite a couple lines of a poem about someone named Jenny. I’ll have to look it up someday.

There was a loose photograph after the last bound picture in the album. It was of her grandmother and another young woman wearing identical cocktail dresses. Oh, how lovely, Jenny thought. The dresses had a graceful boat neckline, long sleeves, a narrow waist, and a bouffant ankle-length skirt.

Prettier than anything on the market today, she thought.

She turned over the picture and read the typed note attached to it:

Sarah wore this dress in the fashion show at Klein’s only hours before she was murdered in it. I’m wearing the other one. It was a backup in case the original became damaged. The designer, Vincent Cole, called it “The Five-Dollar Dress,” because that’s what they were going to charge for it. He said he would lose money on it, but that dress would make his name. It made a big hit at the show, and the buyer ordered thirty, but Cole wouldn’t sell any after Sarah was found in it. He wanted me to return the sample he had given me, but I refused. I think the reason he wanted to get rid of the dress was because Sarah was wearing it when he killed her. If only there was some proof. I had suspected she was dating him on the sly.

Her hand shaking, Jenny put the picture back inside the album. In her delirium the day before she died, Gran had said those names: Sarah … Vincent … Barney … Or had it just been delirium?

A large manila envelope, its bright yellow color faded with time, was next. Opening it, she found it filled with three separate files of crumbling news clippings. There’s no place to read these here, Jenny thought. With the manila envelope tucked under her arm, she walked into the dining area and settled at the table. Careful not to tear the clippings, she began to slide them from the envelope. Looking at the date on the top clipping of the three sets, she realized they had been filed chronologically.

“Murder in Union Square” was the first headline she read. It was dated June 8, 1949. The story followed:

The body of twenty-three-year-old Sarah Kimberley was found in the doorway of S. Klein Department Store on Union Square this morning. She had been stabbed in the back by person or persons unknown sometime during the hours of midnight and five a.m.…

Why did Gran keep all these clippings? Jenny asked herself. Why didn’t she ever tell me about it, especially when she knew I was planning to go into criminal law? I know she must not have talked with Mom about it. Mom would have told me.

She spread out the other clippings on the table. In sequence by date, they told of the murder investigation from the beginning. In the late afternoon, Sarah Kimberley had been modeling the dress she was wearing when her body was found.

The autopsy revealed that Sarah was six weeks pregnant when she died.

Up-and-coming designer Vincent Cole had been questioned for hours. He was known to have been seeing Sarah on the side. But his fiancée, Nona Banks, an heiress to the Banks department store fortune, swore they had been together in her apartment all night.

What did my grandmother do with the dress she had? Jenny wondered. She said it was the prettiest dress she ever owned.

Jenny’s computer was on the table, and she decided to see what she could find out about Vincent Cole. What she discovered shocked her. Vincent Cole had changed his name to Vincenzia and was now a famous designer. He’s up there with Oscar de la Renta and Carolina Herrera, she thought.

The next pile of clippings was about the arrest of Barney Dodd, a twenty-six-year-old man who liked to sit for hours in Union Square Park. Borderline mentally disabled, he lived at the YMCA and worked at a funeral home. One of his jobs was dressing the bodies of the deceased and placing them in the casket. At noon and after work he would head straight to the park, carrying a paper bag with his lunch or dinner. As Jenny read the accounts, it became clear why he had come under suspicion. The body of Sarah Kimberley had been laid out as though she was in a coffin. Her hands had been clasped. Her hair was in place, the wide collar of the dress carefully arranged.

According to the accounts, Barney was known to try to strike up a conversation if a pretty young woman was sitting near him. That’s not proof of anything, Jenny thought. She realized that she was thinking like the deputy district attorney she would soon become.

The last clipping was a two-page article from the Daily News. It was called “Did Justice Triumph?” It was about “The Case of the Five-Dollar Dress,” as the writer dubbed it. At a glance, she could see that long excerpts from the trial were included in the article.

Barney Dobbs had confessed. He signed a statement saying that he had been in Union Square at about midnight the night of the murder. It was chilly, so the park was deserted. He saw Sarah walking across Fourteenth Street. He followed her, and then, when she wouldn’t kiss him, he killed her. He carried her body to the front door of Klein’s and left it there. But he arranged it so that it looked nice, the way he did in the funeral parlor. He threw away the knife as well as the clothes he was wearing that night.

Too pat, Jenny thought scornfully. It sounds to me like whoever got that confession was trying to cover every base. Talk about a rush to justice. Barney certainly didn’t get Sarah pregnant. Who was the father of the baby? Who was Sarah with that night? Why was she alone at midnight (or later) in Union Square?

It was obvious the judge also thought there was something fishy about the confession. He entered a plea of not guilty for Barney and assigned a public defender to his case.

Jenny read the accounts of the trial with increasing contempt. It seemed to her that although the public defender had done his best to defend Barney, he was obviously inexperienced. He should never have put Barney on the stand, she thought. The man kept contradicting himself. He admitted that he had confessed to killing Sarah, but only because he was hungry and the officers who were talking to him had promised him a ham and cheese sandwich and a Hershey bar if he would sign something.

That was good, she thought. That should have made an impression on the jurors.

Not enough of an impression, she decided as she continued reading. Not compared to the district attorney trying the case.

He had shown Barney a picture of Sarah’s body taken at the scene of the crime. “Do you recognize this woman?”

“Yes. I used to see her sometimes in the park when she was having her lunch or walking home after work.”

“Did you ever talk to her?”

“She didn’t like to talk to me. But her friend was so nice. She was pretty, too. Her name was Catherine.”

My grandmother, Jenny thought.

“Did you see Sarah Kimberley the night of the murder?”

“Was that the night I saw her lying in front of Klein’s? Her hands were folded, but they weren’t folded nice like they are in the picture. So I fixed them.”

His attorney should have called a recess, should have told the judge that his client was obviously confused! Jenny raged.

But the defense lawyer had allowed the district attorney to continue the line of questioning, hammering at Barney. “You arranged her body?”

“No. Somebody else did. I only changed her hands.”

There were only two defense witnesses. The first was the matron at the YMCA where Barney lived. “He’d never hurt a fly,” she said. “If he tried to talk to someone and they didn’t respond to him, he never approached them again. I certainly never saw him carry a knife. He doesn’t have many changes of clothes. I know all of them, and nothing’s missing.”

The other witness was Catherine Reeves. She testified that Barney had never exhibited any animosity toward her friend Sarah Kimberley. “If we happened to be having lunch in the park and Sarah ignored Barney, he just talked to me for a minute or two. He never gave Sarah a second glance.”

Barney was found guilty of murder in the first degree and sentenced to life without parole.

Jenny read the final paragraph of the article:

Barney Dodd died at age sixty-eight, having served forty years in prison for the murder of Sarah Kimberley. The case of the so-called Five-Dollar Dress Murder has been debated by experts for years. The identity of the father of Sarah’s unborn baby is still unknown. She was wearing the dress she had modeled that day. It was a cocktail dress. Was she having a romantic date with an admirer? Whom did she meet and where did she go that evening? DID JUSTICE TRIUMPH?

I’d say, absolutely not, Jenny fumed. She looked up and realized that the shadows had lengthened.

At the end, Gran had ranted about Vincent Cole and the five-dollar dress. Was it because he couldn’t bear the sight of it? Was he the father of Sarah’s unborn child?

He must be in his mid-eighties now, Jenny thought. His first wife, Nona Hartman, was a department store heiress. One of the article clips was about her. In an interview in Vogue magazine in 1952, she said she had first suggested that Vincent Cole did not sound exotic enough for a designer, and she urged her husband to upgrade his image by changing his name to Vincenzia. Included was a picture of their over-the-top wedding at her grandfather’s estate in Newport. It had taken place on August 10, 1949, a few weeks after Sarah was murdered.

The marriage lasted only two years. The complaint had been adultery.

I wonder … Jenny thought. She turned back to the computer. The file on Vincent Cole—Vincenzia—was still open. She began searching through the links until she found what she was looking for. Vincent Cole, then twenty-five years old, had been living two blocks from Union Square when Sarah Kimberley was murdered.

If only they had DNA in those days. Sarah lived on Avenue C, just a few blocks away. If she had been in his apartment that night and told him she was pregnant, he easily could have followed her and killed her. Cole probably knew about Barney, a character around Union Square. Could Vincent Cole have arranged the body to throw suspicion on Barney? Maybe he saw him sitting in the park that night?

We’ll never know, Jenny thought. But it’s obvious that Gran was sure he was guilty.

She got up from the chair and realized that she had been sitting for a long time. Her back felt cramped, and all she wanted to do was get out of the apartment and take a long walk.

The charity pick-up truck should be here in fifteen minutes. Let’s be done with it, she thought, and went back into the den. Two boxes were left to open. The one with the Klein label was the first she investigated. Wrapped in blue tissue was the five-dollar dress she had seen in the picture.

She shook it out and held it up. This must be the dress Gran talked about a couple years ago. I had bought a cocktail dress in this color. Gran told me that it reminded her of a dress she had when she was young. She said Grandpa didn’t like to see her wearing it. “A girl I worked with was wearing one like it when she had an accident,” she’d said, “and he thought it was bad luck.”

The other box held a man’s dark blue three-button suit. Why did it look familiar? She flipped open the wedding album. I’m pretty sure that’s what my grandfather wore at the wedding, she thought. No wonder Gran kept it. She could never talk about him without crying. She thought about what her grandmother’s old friends had told her at the wake: “Your grandfather was the handsomest man you’d ever want to see. While he was going to law school at night, he worked as a salesman at Klein’s during the day. All the girls in the store were after him. But once he met your mother, it was love at first sight. We were all jealous of her.”

Jenny smiled at the memory and began to go through the pockets of the suit, in case anything had been left in them. There was nothing in the trousers. She slipped her fingers through the pockets of the jacket. The pocket under the left sleeve was empty, but it seemed as though she could feel something under the smooth satin lining.

Maybe it has one of those secret inner pockets, she thought. I had a suit with a hidden pocket like that.

She was right. The slit to the inner pocket was almost indiscernible, but it was there.

She reached in and pulled out a folded sheet of paper. Opening it, she read the contents.

It was addressed to Miss Sarah Kimberley.

It was a medical report stating that the test had confirmed she was six weeks pregnant.

MARY HIGGINS CLARK’s books are worldwide best sellers. In the United States alone, her books have sold over 100 million copies. Her latest suspense novel, I’ve Got You under My Skin, was published by Simon & Schuster in April 2014. She is an active member of Literacy Volunteers. She is the author of thirty-three previous suspense novels, three collections of short stories, a historical novel, a memoir, and two children’s books. She is married to John Conheeney, and they live in Saddle River, New Jersey.