3

The Ramparts of Christendom

Today, before lunch and not having had any breakfast, seated at our assembly, all of us … did elect, accept, determine and proclaim and send word to the streets, that the aforementioned most illustrious Lord Ferdinand should be true, lawful, unchallenged and natural king and master of this whole glorious kingdom of Croatia.

Diet of Cetingrad, New Year’s Day, 15271

A more determined foe than the Mongols appeared in the form of the Ottoman Turks. In the 1280s Osman I, a minor Turkic ruler, established a state in north-west Anatolia around the city of Bursa. From this stronghold, his descendants carried on a campaign of territorial expansion that was to consume the Byzantine Empire within a century and a half, give the Ottomans control over the entire Balkan peninsula and bring their armies to the gates of Vienna. By the mid-fourteenth century, the Ottomans already had a toe-hold in Europe, around Gallipoli. From there they subdued the Bulgarians and encircled Constantinople from the west, as well as the east. The strategic city of Adrianople, west of Constantinople, fell in 1361 and was soon proclaimed the Ottoman capital, illustrating the importance that they attached to their conquests in Europe.

From Adrianople, Sultan Murat I began the conquest of Serbia. Under the Nemanja dynasty, which had united the Serbian lands in the 1160s, Serbia had expanded to the point where King Dušan (1331–56) controlled most of the Balkan peninsula between the Danube and the Aegean. Dušan gave himself the title of tsar and in 1345 elevated the head of the Serbian Church, the Archbishop of Pe , to the status of patriarch, as it took a patriarch to crown an emperor. The Serbian Empire was short-lived, however, and scarcely outlasted Dušan’s death. Under his son, Uroš V, the tsardom dissolved into a patchwork of petty lordships. Uroš was driven from the throne in 1366 and, after his death in 1371, the royal house of Nemanja died out. Serbia by then was so divided that the most important Serbian princely ruler, Lazar, did not even claim the title of tsar but remained a mere knez. As in Croatia in the 1090s, the extinction of the native dynasty gave powerful neighbours the chance to invade. From the west, King Tvrtko of Bosnia claimed the throne of Serbia for himself. But the most serious threat came from the east. By 1386 Ottoman armies had overrun southern Macedonia and reached the city of Niš, north of Kosovo. Lazar attempted, too late, to reunite the Serbian factions against a common enemy. On 28 June 1389, Vidov Dan – St Vitus’ Day – Lazar’s army encountered Murat’s invaders on the undulating plain of Kosovo Polje. The Serbs were not alone, and counted a substantial number of Bosnians, Bulgars, Croats, Wallachians and Albanians in their ranks. In the battle that followed, Murat was killed along with Lazar. But the result was an Ottoman victory, which sounded the death knell of the Serbian state.

, to the status of patriarch, as it took a patriarch to crown an emperor. The Serbian Empire was short-lived, however, and scarcely outlasted Dušan’s death. Under his son, Uroš V, the tsardom dissolved into a patchwork of petty lordships. Uroš was driven from the throne in 1366 and, after his death in 1371, the royal house of Nemanja died out. Serbia by then was so divided that the most important Serbian princely ruler, Lazar, did not even claim the title of tsar but remained a mere knez. As in Croatia in the 1090s, the extinction of the native dynasty gave powerful neighbours the chance to invade. From the west, King Tvrtko of Bosnia claimed the throne of Serbia for himself. But the most serious threat came from the east. By 1386 Ottoman armies had overrun southern Macedonia and reached the city of Niš, north of Kosovo. Lazar attempted, too late, to reunite the Serbian factions against a common enemy. On 28 June 1389, Vidov Dan – St Vitus’ Day – Lazar’s army encountered Murat’s invaders on the undulating plain of Kosovo Polje. The Serbs were not alone, and counted a substantial number of Bosnians, Bulgars, Croats, Wallachians and Albanians in their ranks. In the battle that followed, Murat was killed along with Lazar. But the result was an Ottoman victory, which sounded the death knell of the Serbian state.

A much reduced Serbian principality survived the Battle of Kosovo by several decades by paying tribute to the Ottomans, and was extinguished only by the fall of the fortress at Smederevo, near Belgrade, in 1459. But after 1389 it was clear it would only be a matter of time before Serbia eventually succumbed.

The defeat of the Serbs at Kosovo Polje opened the way to the rest of the Balkans and allowed the Ottomans to transfer their attention to Serbia’s western neighbour, Bosnia. This was an easier challenge. Remote and sparsely inhabited, Bosnia was a kingdom divided against itself owing to the unresolved tripartite struggle for supremacy between Catholics, followers of the Bosnian Church and Serb Orthodox. The partial return of many Bosnians to Catholicism through the efforts of Franciscan missionaries in the mid-fourteenth century, and the annexation of Catholic land in Dalmatia in the late fourteenth century, boosted the Catholic element in Bosnia. But Bosnia remained a country weakened by religious incoherence. In the south-east and east, along the River Drina, much of the population was Serb Orthodox. In the north and north-west and in the valleys of central Bosnia, where the Franciscans had concentrated their efforts, Catholicism was the dominant faith. In parts of the centre, at the core of the old Bosnian state, were the depleted remnants of the Bosnian Church. It used to be believed that disappointed followers of the Bosnian Church who resented forced conversion to Catholicism opened the gates of Bosnia’s fortresses to the invading Muslims. It is more likely that Bosnia collapsed in the 1450s and 1460s because it was poor, underpopulated and divided into virtually independent fiefdoms.

The Bosnians did not long outlast the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The capture of the Byzantine capital released more troops for the Ottomans’ Balkan campaigns. Vrhbosna, later renamed Sarajevo, fell in 1451. The rest succumbed almost without a fight in 1462–3. Saptom pade Bosna, it was said (Bosnia fell in a whisper). One by one the towns opened their gates to the advancing Turks, forcing the wretched King, Stjepan Tomaševi (1461–3), to flee from one redoubt to another. After Jajce surrendered, the King took refuge in Klju

(1461–3), to flee from one redoubt to another. After Jajce surrendered, the King took refuge in Klju ; from there he was dragged back to Jajce, on a promise he would not be harmed. Notwithstanding his pledge, Sultan Muhammed II had the King beheaded in his tent, outside Jajce. It was not quite the end of Christian Bosnia. In the 1460s the energetic King of Hungary–Croatia, Mathias I Corvinus (1458–90), turned back the tide and reoccupied large parts of northern and central Bosnia, including Jajce. In spite of this, the Ottomans continued to stream into Bosnia and Croatia as well, provoking desperate appeals from the Croat nobles for foreign support. Mathias Corvinus resented the Frankopan Lord of Krk’s request for Venetian support against the Turks and confiscated the Frankopans’ prize possession – the town of Senj. Fearing that the King planned to confiscate the island of Krk as well, the Frankopans surrendered it to Venice in 1480.

; from there he was dragged back to Jajce, on a promise he would not be harmed. Notwithstanding his pledge, Sultan Muhammed II had the King beheaded in his tent, outside Jajce. It was not quite the end of Christian Bosnia. In the 1460s the energetic King of Hungary–Croatia, Mathias I Corvinus (1458–90), turned back the tide and reoccupied large parts of northern and central Bosnia, including Jajce. In spite of this, the Ottomans continued to stream into Bosnia and Croatia as well, provoking desperate appeals from the Croat nobles for foreign support. Mathias Corvinus resented the Frankopan Lord of Krk’s request for Venetian support against the Turks and confiscated the Frankopans’ prize possession – the town of Senj. Fearing that the King planned to confiscate the island of Krk as well, the Frankopans surrendered it to Venice in 1480.

Many Christians in Bosnia converted to Islam over the course of several generations. But many others refused, and emigrated from Bosnia to Croatia. Among the refugees were hundreds of minor nobles, who brought to Croatia little but their titles. Many settled in the Turopolje district, south of Zagreb, where they formed a highly distinct community with their own political privileges until the mid-nineteenth century. The most enterprising Catholic refugees fled further afield, to Italy and beyond. Take the career of the humanist Juraj Dragiši . Born in Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia in 1445, his family fled when he was a small child and took refuge in a Franciscan monastery in Dubrovnik. Dragiši

. Born in Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia in 1445, his family fled when he was a small child and took refuge in a Franciscan monastery in Dubrovnik. Dragiši entered the order, studying in Rome, Padua, Paris and Oxford. He spent most of his life in Florence, where he was close to the Medici family, acting as tutor to Piero, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Returning to Dubrovnik in the 1490s, he was later appointed Bishop of Cagli in Umbria in 1507. His literary output was considerable, and included works in defence of Savonarola and of humanism in opposition to the German Dominicans. In one of the last controversies of his life (he died in 1520) he strongly opposed moves to suppress Jewish books that refuted the claims of Christianity.

entered the order, studying in Rome, Padua, Paris and Oxford. He spent most of his life in Florence, where he was close to the Medici family, acting as tutor to Piero, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Returning to Dubrovnik in the 1490s, he was later appointed Bishop of Cagli in Umbria in 1507. His literary output was considerable, and included works in defence of Savonarola and of humanism in opposition to the German Dominicans. In one of the last controversies of his life (he died in 1520) he strongly opposed moves to suppress Jewish books that refuted the claims of Christianity.

After the fall of Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia, it was the turn of Hungary and Croatia. As in Serbia and Bosnia, the final, decisive onslaught was preceded by tentative raids, designed to soften up the enemy. The crucial encounter for the Croats took place in 1493 at the Krbavsko Polje, in the hilly moorland of Lika, south-west of Zagreb. The result, as in the Battle of Kosovo, was a rout. The leaders of several hundred of Croatia’s noble families were killed, wiping out the country’s leadership at a stroke. The way was now open for the Turks to penetrate the rest. A year after Krbavsko Polje, the Turks captured Ilok, a strategic fortress in eastern Slavonia. By 1500 they had taken the Dalmatian port of Makarska. From 1503 to 1512 an uneasy peace held between the Turks on one side and the Hungarians and Croats on the other. But it was only a breathing space while the Ottomans regrouped. After the accession of Sultan Selim in 1512, they launched new offensives. In 1513 the Ottomans overran the town of Modruš, an episcopal see in Lika. By this time the lines of defence of the Hungarians and Croats were shot to pieces, and towns fell in rapid succession. Modruš was followed by Doboj, Tuzla and Bijeljina, the three principal Croat and Hungarian outposts in the north of Bosnia. The Bishop of Modruš, Šimon Kozi i

i , described the atmosphere of despair in contemporary Croatia to the bishops of the Lateran Council, recalling how he had been ‘often forced, while celebrating divine offices, to discard ecclesiastical garments, take weapons, run to the city gates and … incite the scared population to heroically resist the bloody enemy’.2

, described the atmosphere of despair in contemporary Croatia to the bishops of the Lateran Council, recalling how he had been ‘often forced, while celebrating divine offices, to discard ecclesiastical garments, take weapons, run to the city gates and … incite the scared population to heroically resist the bloody enemy’.2

The ecclesiastical and civil authorities in Zagreb were acutely aware that their city was also threatened and set to work surrounding the cathedral with high walls and towers. Work began under Bishop Osvald Thuz (1466–99), who was given a new home in the Kaptol by King Mathias after his old residence in  azma, in western Slavonia, became too close to the Ottoman frontline. Osvald’s work was followed up by his successor, Luka Baratin, who used the legacy of 10,000 florins left by Osvald to continue work on the new fortifications. In 1510 the Bishop had to apply to Pope Julian II for permission to demolish the Church of St Emerika, which lay in the path of the proposed west-facing defences, in front of the cathedral. The Bishop told Rome of the urgent need to put up the fortifications, as the cathedral lay ‘near the land of the Turks who attack these regions with frequent incursions. It is to be feared that the church, if not secured by the erection of good defences, could in a short time be destroyed by the attacks of the said Turks.’3 The work of building a ring of towers was extremely dangerous, as the nearest Ottoman forces were only a few miles south of Zagreb on the southern bank of the River Sava. While the building was in progress the canons paid a scout, Šimun Horvat, to spy on the Ottoman positions south of the river. However, the Turks held off during the vital period of construction and the work was virtually finished by 1520. The battlements gave Zagreb cathedral the appearance of a fortified castle as much as a church of God, an appearance it retained until the disastrous modernisation of the cathedral district at the end of the nineteenth century; the towers were equipped with guns and cannons that remained ready for use until the early eighteenth century, when they were removed finally to a museum.

azma, in western Slavonia, became too close to the Ottoman frontline. Osvald’s work was followed up by his successor, Luka Baratin, who used the legacy of 10,000 florins left by Osvald to continue work on the new fortifications. In 1510 the Bishop had to apply to Pope Julian II for permission to demolish the Church of St Emerika, which lay in the path of the proposed west-facing defences, in front of the cathedral. The Bishop told Rome of the urgent need to put up the fortifications, as the cathedral lay ‘near the land of the Turks who attack these regions with frequent incursions. It is to be feared that the church, if not secured by the erection of good defences, could in a short time be destroyed by the attacks of the said Turks.’3 The work of building a ring of towers was extremely dangerous, as the nearest Ottoman forces were only a few miles south of Zagreb on the southern bank of the River Sava. While the building was in progress the canons paid a scout, Šimun Horvat, to spy on the Ottoman positions south of the river. However, the Turks held off during the vital period of construction and the work was virtually finished by 1520. The battlements gave Zagreb cathedral the appearance of a fortified castle as much as a church of God, an appearance it retained until the disastrous modernisation of the cathedral district at the end of the nineteenth century; the towers were equipped with guns and cannons that remained ready for use until the early eighteenth century, when they were removed finally to a museum.

The Croats did not accept the conquest of the country with resignation. Several notable nobles and ecclesiastics held up the Turkish advance for a while and earned the admiration of Christendom for their valour. In 1519 Pope Leo X described Croatia as Antemurale Christianitatis – the ramparts, or bulwark, of Christendom. Petar Berislavi , who was both bishop of Zagreb and ban, stemmed the tide of the Turkish advance with particular effect by uniting Croatia’s quarrelsome noble families in defence of the realm. Although the Turks were checked by such charismatic figures as Berislavi

, who was both bishop of Zagreb and ban, stemmed the tide of the Turkish advance with particular effect by uniting Croatia’s quarrelsome noble families in defence of the realm. Although the Turks were checked by such charismatic figures as Berislavi , they were never pushed back. Each hard-earned victory left the Croats exhausted and more vulnerable to the next assault.

, they were never pushed back. Each hard-earned victory left the Croats exhausted and more vulnerable to the next assault.

Ban Berislavi ’s death in 1520 in battle with the Turks at Vražja mountain, near Korenica, coincided with the accession of the greatest of the Ottoman sultans. Suleyman the Magnificent, and from the first year of Suleyman’s reign the Croats endured one defeat after another. In 1521 the crucial Hungarian fortress on the Danube at Belgrade fell. One year later the Ottomans took another highly strategic town, the old royal seat of Knin, which held the pass from northern Croatia to Dalmatia. Although still subjects of the King of Hungary, most Croats had given up hope of receiving military aid from Hungarians after the death of Mathias Corvinus in 1490. He had proved an able defender of Hungary’s frontiers against the Turks, but the Hungarian nobles resented his attempts to build up the crown and on his death elected the pliant Ladislas of Bohemia as king. Under Ladislas, who died in 1516, and his son, Louis II Jagellion (1516–26), the powers of the crown evaporated and the aristocracy gained almost total control over the affairs of state. One consequence was a marked deterioration in the status of the peasants. Lacking royal protection, the system of robota (forced labour) on noble estates became more burdensome and the peasants were reduced to the status of chattels of the nobles, a development that diminished their interest in defending the country from the Turks.

’s death in 1520 in battle with the Turks at Vražja mountain, near Korenica, coincided with the accession of the greatest of the Ottoman sultans. Suleyman the Magnificent, and from the first year of Suleyman’s reign the Croats endured one defeat after another. In 1521 the crucial Hungarian fortress on the Danube at Belgrade fell. One year later the Ottomans took another highly strategic town, the old royal seat of Knin, which held the pass from northern Croatia to Dalmatia. Although still subjects of the King of Hungary, most Croats had given up hope of receiving military aid from Hungarians after the death of Mathias Corvinus in 1490. He had proved an able defender of Hungary’s frontiers against the Turks, but the Hungarian nobles resented his attempts to build up the crown and on his death elected the pliant Ladislas of Bohemia as king. Under Ladislas, who died in 1516, and his son, Louis II Jagellion (1516–26), the powers of the crown evaporated and the aristocracy gained almost total control over the affairs of state. One consequence was a marked deterioration in the status of the peasants. Lacking royal protection, the system of robota (forced labour) on noble estates became more burdensome and the peasants were reduced to the status of chattels of the nobles, a development that diminished their interest in defending the country from the Turks.

As Hungary crumbled from within, the Croat nobles pondered transferring their loyalty to the Habsburg emperors. After the fall of Knin, delegations of Croat and Hungarian nobles attended the Imperial Diets at Worms and Nuremberg in 1521 and 1522 in search of men. At the Diet of Nuremberg. Bernardin Frankopan, the leader of the Croat delegation, made a personal appeal to the Emperor Charles V, reminding him that the Pope had only recently referred to Croatia as the bulwark of Christendom. ‘Think how much evil will happen to the Christian world if Croatia should fall,’ he urged. The Diet offered to raise and fund troops to defend Croatia’s exposed southern flank, partly because the Estates of Inner Austria were becoming increasingly worried about their own defences if Croatia should fall. But the Croats were not the only item, or even the main one, on the Imperial Diet’s agenda. Charles V was preoccupied with dividing his empire between the Spanish and Austrian branches of the Habsburg family and with the storm stirred up by Martin Luther. At Worms in 1521 Luther was placed under an imperial ban and the Emperor was more interested in suppressing heresy in his dominions than in bolstering the King of Hungary’s neglected Croatian subjects.

The Ottoman invasion of Croatia was no ordinary war of conquest. It was not like the Pacta Conventa of 1102, when the country had exchanged one dynasty for another. It entailed the almost complete destruction of civilised life, the burning of towns, villages and their churches and monasteries, the murder of the leading citizens, the mass flight of the peasants, the laying waste of the countryside and the enslavement of thousands of those who failed to flee in time. The terror aroused by the Turks induced many petty Balkan princes to sue for peace, in the hope of salvaging something by accepting Turkish over-lordship. The Croat and Hungarian nobles were not immune to the temptation of dealing with the Turks. Some acted out of plain fear, others out of suspicions about the Habsburgs’ motives.

But the Hungarian crown did not sue for peace and so the Ottoman juggernaut rolled on. The consequences were frightful for ordinary people. In 1501, officials in Venetian-ruled Zadar reported that about 10,000 people in the countryside around the city had simply disappeared, presumably dragged off into slavery, during the course of three big Turkish raids. In 1522 the Renaissance poet and scholar of Split, Marko Maruli (1450–1524), author of the first epic on a secular theme in Croatian, Judith, gave this graphic account of the miserable air of uncertainty in the Dalmatian cities. In a letter to Pope Hadrian VI he wrote: ‘They harass us incessantly, killing some and leading others into slavery. Our goods are pillaged, our cattle led off, our villages and settlements are burned. Our Dalmatian cities are not yet besieged or attacked due to some, I know not what, alleged peace treaty. But only the cities are spared and all else is open to rapine and pillage.’4

(1450–1524), author of the first epic on a secular theme in Croatian, Judith, gave this graphic account of the miserable air of uncertainty in the Dalmatian cities. In a letter to Pope Hadrian VI he wrote: ‘They harass us incessantly, killing some and leading others into slavery. Our goods are pillaged, our cattle led off, our villages and settlements are burned. Our Dalmatian cities are not yet besieged or attacked due to some, I know not what, alleged peace treaty. But only the cities are spared and all else is open to rapine and pillage.’4

Dubrovnik escaped this fate by conceding nominal sovereignty, though not real independence, to the Sultan, paying an annual tribute. Lying on the southern tip of Dalmatia, the city’s merchant princes had sensed the danger that the Ottomans presented early on. They had tried without much success to rouse the rest of Europe to throw back the Turks before they advanced too far. In 1441 the city sent an appeal to the Pope and the King of Hungary urging them to combine to stop the Turks in their tracks. The appeal did not go unanswered and in 1442 Pope Eugene IV urged all the Christian powers to collect ships for an expedition to the Straits of Constantinople to save the city from collapse and prevent the free flow of Turkish armies across the Bosphorus into Europe.

Surviving records throw light on the way that the crusade was organised in Dubrovnik. A committee consisting of three procurators was appointed by the Senate to meet with a papal representative twice daily for the purpose of collecting money at a point near the Rector’s palace. There were two keys to the cash box, one in the control of the city’s representatives and the other in the hands of the Pope’s representative. In October 1443, the authorities gave out alms to the poor with instructions that they should pray for victory over the Turks, and in December of that year the city organised three days of religious processions to give thanks for the victories of the Hungarian King over the Turks at battles near Niš and Sofia. In 1444 the money collected in Dubrovnik for the expedition was handed over to a papal legate, and the ships supplied by Venice and the Duke of Burgundy arrived in the harbour. Unfortunately it was all wasted effort. At Varna, on 10 November, the Turks gained a crushing victory over the Hungarians and the hope of stopping the Turkish advance into Europe was dashed. The expeditionary fleet trailed back to Dubrovnik, its mission unaccomplished. It was the failure of the last papal crusade that made Dubrovnik rethink its allegiance to Hungary–Croatia. Hitherto, the city had banked on the Christian powers co-ordinating their efforts to halt the Turkish advance. From then on Dubrovnik pragmatically accepted Ottoman domination over south-east Europe and marshalled its efforts towards preserving its independence under Ottoman protection.

The Croats had made their stand at Krbavsko Polje in 1493. The turn of the Hungarians came in August 1526 when the news reached Buda of a large Turkish army moving northwards towards Hungary. The reports triggered fresh appeals to the Habsburgs and the papacy for aid, but there was no answer. Although Queen Maria of Hungary was the sister of Charles V’s younger bother. Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, Ferdinand himself seems not to have been unduly concerned about the fate of his brother-in-law. The Pope’s treasury was empty.

The Ottomans had waited longer than they needed. After the capture of Belgrade in 1521, they could have marched north immediately, as there was little to stop them on the flat plains north of the Danube. Instead they turned back. After the fall of Belgrade, the Hungarians did nothing to shore up their tottering defences. Conventional wisdom is that Louis II would have done best to fall back with his small army on Buda. Instead he raced south to meet the Ottomans on an exposed plain at Mohacs, in southern Hungary. Suleyman crossed the River Drava on 21 August with a force of at least 50,000 men. The result was annihilation. Louis II had mustered only about 20,000 Hungarians. A small supporting army of 6,000 Croats on horseback – among them the bishops of Zagreb, Senj and Djakovo – and 3,000 infantry failed to arrive. The fighting was over within one hour. The King perished: it was believed by drowning in a stream.

The outcome of Mohacs held great significance for the future of Central Europe. The Battle of Kosovo had opened up the Balkans to the Ottomans; Mohacs opened the road to the heart of the continent. Within a week the Sultan was in Buda.

Hungary was then torn by civil war. On one side was an anti-Habsburg faction, led by Janos Zapolya, an ambitious Transylvanian nobleman who was prepared to become the Sultan’s vassal in order to prevent foreigners from taking the throne. On the other side were the supporters of the Archduke Ferdinand, backed by the Queen Maria.

Ferdinand had no problem in confirming his rights to Louis’ Bohemian kingdom, where he was elected king by an assembly in Prague in October 1526. But the feud in Hungary was not so easily solved, even after he was elected king of Hungary in Pressburg on 17 December. In the east, Zapolya held a rival coronation. The struggle between the Habsburg and Zapolya factions enabled the Ottomans to consolidate their hold over most of Hungary. The Habsburgs were left in control of a sliver of land in the west and in the north, in the territory that comprises modern Slovakia.

The rout at Mohacs was a momentous event for the Croats. The joint kingdom established in 1102 was ended. The Croats were without a ruler. A few days after Ferdinand’s coronation in Pressburg the Sabor assembled at Cetingrad, near Biha , to elect him as king of Croatia. Most Croats backed the Habsburg candidate, although they were determined to make use of the choice to reaffirm Croatia’s privileges and its status as a kingdom.

, to elect him as king of Croatia. Most Croats backed the Habsburg candidate, although they were determined to make use of the choice to reaffirm Croatia’s privileges and its status as a kingdom.

On New Year’s Day 1527 the Sabor met at the Church of the Visitation of St Mary in the Monastery of the Transfiguration under the presidency of the Bishop of Knin and the heads of the Zrinski and Frankopan families.

Following final negotiations with three Habsburg plenipotentiaries, they elected Ferdinand as king of Croatia. The Sabor made it clear to Ferdinand that they had elected him in the hope of gaining more military aid against the Ottomans – ‘taking into account the many favours, the support and comfort which, among the many Christian rulers, only his devoted royal majesty graciously bestowed upon us, and the kingdom of Croatia, defending us from the savage Turks …’. The ceremony closed with a Te Deum and ‘a tumultuous ringing of bells’.5 The document of allegiance was sealed with the red-and-white coat of arms of Croatia, which marks the first known occasion on which the chequer-board symbol was used as Croatia’s emblem.

The Sabor of Slavonia, which was dominated by Hungarian magnates, did not share the Croats’ enthusiasm for the Habsburgs. In 1505 it had pledged never to accept another foreign (non-Hungarian) prince, and supported Zapolya.

Krsto Frankopan, the brother of Bernardin, emerged as a powerful supporter of Zapolya in Slavonia and joined him in flirting with the Turks, although he was killed in the early days of the civil war. Simon Erdody, the Bishop of Zagreb, was another pillar of the pro-Zapolya faction, laying siege to his own diocesan capital in 1529 and burning the outlying hamlets. A force loyal to Ferdinand raised the siege of Zagreb, destroyed the Kaptol, and extinguished this threat to the Habsburg claim. In 1533 a joint session of the Sabors of Slavonia and Croatia–Dalmatia confirmed Ferdinand’s title to all the Croat lands.

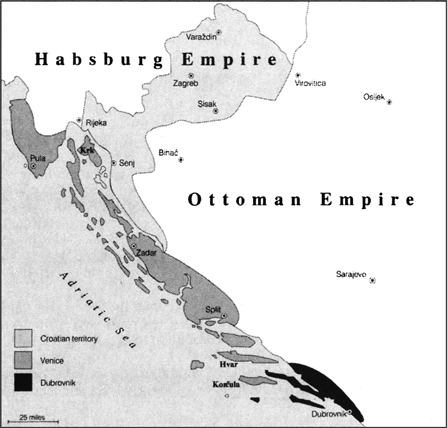

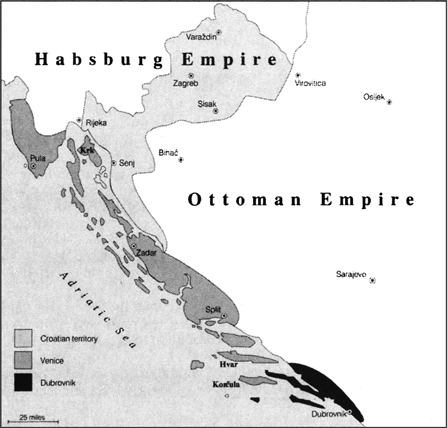

Croatia at the end of the sixteenth century

Croat hopes of recovering large tracts of the country with the aid of the Habsburgs were disappointed. As an election sweetener, before the assembly in Cetingrad, Ferdinand had promised to pay for 1,000 cavalry and 1,200 infantry to defend the Croatian border, while the Estates of Inner Austria, Carinthia, Carniola and Styria voted money to supply garrisons in the frontline cities of Biha , Senj, Krupa and Jajce in Bosnia. But this investment was insufficient to keep the Ottomans at bay. The Habsburgs’ pockets were not deep enough, and the complicated arrangement of their possessions, in which there were many estates with overlapping jurisdictions, made it difficult to harness their resources. Instead, there were stop-gap measures and half-built castles, manned by soldiers who often were not paid for years on end.

, Senj, Krupa and Jajce in Bosnia. But this investment was insufficient to keep the Ottomans at bay. The Habsburgs’ pockets were not deep enough, and the complicated arrangement of their possessions, in which there were many estates with overlapping jurisdictions, made it difficult to harness their resources. Instead, there were stop-gap measures and half-built castles, manned by soldiers who often were not paid for years on end.

The results on the ground were depressing. From 1527 to the 1590s the Croats continued to lose territory. In 1527 the Ottomans overran Udbina, in Lika. In the same year the last Christian-held fortress in central Bosnia, at Jajce, also collapsed. By the end of the 1530s, the Turks had mopped up the last spots of resistance on the southern bank of the River Sava in northern Bosnia, and had advanced through Slavonia as far west as Našice and Požega. In Dalmatia, the Turks conquered most of the land that was not occupied already by Venice. Obrovac fell in 1527 and in 1537 the fortress of Klis, the last Croat stronghold south of the Velebit mountains, succumbed. In the 1540s the pace of the Ottomans’ advance in Slavonia was equally relentless, as they pushed westwards as far as the line between Virovitica,  azma and Sisak.

azma and Sisak.

During the next three decades they continued their advance through the north-west of Bosnia in the direction of the Habsburg garrison town of Karlovac, south-west of Zagreb. The biggest disaster of the period was the loss of the royal free city of Biha in 1592. The town was razed and the inhabitants – those who were not killed – fled. The loss of Biha

in 1592. The town was razed and the inhabitants – those who were not killed – fled. The loss of Biha to Croatia was permanent. The city was rebuilt and revived as a Muslim city surrounded by Serb Orthodox peasants. The fall of Biha

to Croatia was permanent. The city was rebuilt and revived as a Muslim city surrounded by Serb Orthodox peasants. The fall of Biha was almost followed by the loss of Sisak, which was attacked in 1593 by an Ottoman force under Hasan Predojevi

was almost followed by the loss of Sisak, which was attacked in 1593 by an Ottoman force under Hasan Predojevi , the Pasha of Bosnia. Had Sisak crumbled, the way would have been open to Zagreb. The threat threw the Sabor into panic and a hastily recruited force of about 5,000 professional soldiers under the Ban, Thomas Erdody, was despatched to the town. The Ottomans were too confident. The Croats, made fearless by terror of the consequences of failure, took the initiative and fell on the Turks with ferocity. This rare and surprising victory was not followed up. An attempt to recapture neighbouring Petrinja, where the Ottomans had erected a fortress, was not successful. Nevertheless, the Ottomans had reached their high-water mark in Croatia by the end of the 1590s, leaving a strip of territory around Zagreb, Karlovac and Varaždin under the control of the Sabor and the Habsburgs.

, the Pasha of Bosnia. Had Sisak crumbled, the way would have been open to Zagreb. The threat threw the Sabor into panic and a hastily recruited force of about 5,000 professional soldiers under the Ban, Thomas Erdody, was despatched to the town. The Ottomans were too confident. The Croats, made fearless by terror of the consequences of failure, took the initiative and fell on the Turks with ferocity. This rare and surprising victory was not followed up. An attempt to recapture neighbouring Petrinja, where the Ottomans had erected a fortress, was not successful. Nevertheless, the Ottomans had reached their high-water mark in Croatia by the end of the 1590s, leaving a strip of territory around Zagreb, Karlovac and Varaždin under the control of the Sabor and the Habsburgs.

The Habsburgs called the string of garrisoned castles they maintained in Croatia the Military Frontier – Vojna Krajina in Croatian. It was not a piece of territory but simply a series of forts manned by German mercenaries who were backed up by local troops. At first, most of these local soldiers were Croat refugees who had fled north from Dalmatia or trekked out of the interior of Bosnia, ahead of the Ottoman advance. The soldiers manning these garrisoned forts became known as frontiersmen – grani ari in Croatian.

ari in Croatian.

A decade after Ferdinand established his rule in Croatia the first changes in the Military Frontier’s organisation were made, with the appointment of the first captain general of the Krajina, Nicholas Juriši . In 1553 there were other important changes. The Krajina was placed under a single military commander who was made virtually independent of the ban and Sabor, with whom he had only to co-operate, not defer to. In 1578, the finances of the Frontier were remodelled with the establishment in Graz of the Hofkriegsrat, or Court War Chancellery. For Croatia’s future, one of the most important decisions of the era was the decision to found a new garrison town south-west of Zagreb, called Karlstadt or, in Croatian, Karlovac. The new town was built on marshy land and appears to have had difficulty in recruiting anyone to come and live in it. The royal charter of the city in 1581 made clear that all settlers were welcome, offering citizenship to all comers, ‘whether of German, Hungarian, Croatian or any other nationality’.6

. In 1553 there were other important changes. The Krajina was placed under a single military commander who was made virtually independent of the ban and Sabor, with whom he had only to co-operate, not defer to. In 1578, the finances of the Frontier were remodelled with the establishment in Graz of the Hofkriegsrat, or Court War Chancellery. For Croatia’s future, one of the most important decisions of the era was the decision to found a new garrison town south-west of Zagreb, called Karlstadt or, in Croatian, Karlovac. The new town was built on marshy land and appears to have had difficulty in recruiting anyone to come and live in it. The royal charter of the city in 1581 made clear that all settlers were welcome, offering citizenship to all comers, ‘whether of German, Hungarian, Croatian or any other nationality’.6

The first military commander of the Krajina, Hans Ungnad, an Austrian from Carniola, was not a great success. An assault on Varaždin was held off in 1553, thanks to the efforts of Ban Nicholas Zrinski, who died in heroic circumstances in battle in 1566 while defending the fortress of Szeged in southern Hungary against the aged Sultan Suleyman, who also died there. But in 1556 the town of Kostajnica, an important border town on the banks of the River Una, was lost to the Ottomans. After this loss Ungnad was dismissed. There may have been other reasons for his removal, as he was a Lutheran and he left afterwards for the Lutheran bastion of Wittenberg. Ungnad had complained that the problem was not his ability as a commander but the shortage of resources. The complaint recurred with depressing regularity. A myth grew up about the Krajina of garrison towns manned by fearless, seasoned fighters. The reality was a series of dilapidated fortresses that held off the Ottomans mainly because the Ottomans themselves had become inert. In the 1570s there were only about 3,000 soldiers in the whole of the Krajina, which goes some way towards explaining why towns continued to fall with such alarming frequency. The situation on the Frontier, which was always ramshackle, got worse after the death of the Emperor Maximilian in 1576, for his successor, Rudolf, was uninterested in government and let matters slide while he pursued his own interests in the mysteries of magic in Prague. A report in 1577 recorded a lamentable state of affairs in the garrisons of Senj, Biha , Varaždin and Koprivnica. But that was nothing compared to the appalling state of affairs in 1615, when a horrified visitor to Karlovac described the guns as having rusted away, the powder wet and the soldiers half-starved scavengers wandering around the tatty fortress half naked.

, Varaždin and Koprivnica. But that was nothing compared to the appalling state of affairs in 1615, when a horrified visitor to Karlovac described the guns as having rusted away, the powder wet and the soldiers half-starved scavengers wandering around the tatty fortress half naked.

Changes in the administration of the Krajina in the last half of the sixteenth century caused profound disquiet in the Sabor. The Croats had elected the Habsburgs as their king in the hope of military aid against the Ottomans. What they got was almost a separate state within their shrunken borders, which was run with little reference to Croat institutions. But there was little the Sabor could do about these royal intrusions except protest with growing frequency their right to control Croatia’s internal affairs. Their protests counted for little. The Habsburgs were keen to continue the development of the Krajina from a string of forts into a territory, which really acted as a kind of laboratory for absolutism. The only weapon in the hands of an assembly like the Croatian Sabor was money, or rather the ability to withhold it. But here the Sabor was on shaky ground, for Croatia’s revenues were too small to count for much and the defence of the Krajina was paid for by the Estates of Inner Austria, not by the Sabor.

What began as a political dispute between the Sabor and the Habsburgs over the Krajina then assumed additional ethnic and religious overtones, as the Krajina was settled on the invitation of the Habsburgs with Vlachs, or Morlachs as they were also known, most of whom belonged to the Serbian Orthodox Church although a minority were Catholic.

The debate over the origin of the Orthodox settlers in the Krajina is highly contentious. Serb scholars have usually insisted that the Orthodox Vlachs were ethnic Serbs, in order to boost the claim that the Krajina should be attached to a Serbian state. Croat scholars have insisted with equal vehemence that the Orthodox Vlachs began to identify themselves as Serbs in the nineteenth century under the pressure of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The debate is somewhat anachronistic as these national categories had little relevance in the feudal or early modern era to peasants and shepherds. It would probably be fair to say that, whether or not the Vlachs originally migrated from Serbia, they did not identify as Serbs until the last century.

The precise route by which the Vlachs reached Croatia is obscure. It would appear that they were pastoral, nomadic people who lived in the mountains of the Dalmatian interior and in Bosnia. They were darker skinned than the Croats, hence the name Morlach, from Maurus, Latin for black. One Croat theory is that they were the inhabitants of Dalmatia before the arrival of the Slavs, having been settled there as legionaries by the Romans. According to this idea, they were pushed out of the lowlands by the Slavs, and forced to retreat to inaccessible mountainous territory, from where they returned after the Croats fled their villages ahead of the Ottoman invasion.

The arrival of the Orthodox settlers in the Krajina in the sixteenth century added a new note of religious conflict to Croatia’s internal affairs, though the question of religion was only a part of the Sabor’s grievances. In order to attract settlers into Croatia’s war-wasted borderlands the Habsburgs exempted the incomers from the feudal system. There were no serfs, merely soldiers who were expected to spend their lives in military service in exchange for their liberty. This greatly disturbed the Sabor, which was an assembly of estates, representing nobles, bishops and deputies from the royal boroughs. Many of them, like the Bishop of Zagreb, held great estates and owned thousands of serfs. In the tiny patch of Croatia that had remained free of Ottoman rule, the Croat noble class consolidated the harsh feudal system that had spread in from Hungary. What the Sabor found objectionable in the administration of the Krajina was not just the intrusion of the Orthodox Church but the free status of the peasants who lived there. The mere fact that they existed was a temptation to the down-trodden serfs on their estates. The nobles’ concern about the existence of the free peasants of the Krajina dovetailed with the advance of the Counter-Reformation, whose great champion in Croatia was Juraj Draškovi , Bishop of Zagreb and Ban of Croatia. Draškovi

, Bishop of Zagreb and Ban of Croatia. Draškovi believed sincerely in the revival of Catholicism in Croatia and founded the country’s first seminary in Zagreb. But he also believed with equal sincerity in maintaining the full rigours of the feudal system and took a leading part in crushing a desperate rebellion by the serfs in 1573 led by Matija Gubec, which the Bishop terminated by arresting Gubec and crowning him with molten iron for his impertinence.

believed sincerely in the revival of Catholicism in Croatia and founded the country’s first seminary in Zagreb. But he also believed with equal sincerity in maintaining the full rigours of the feudal system and took a leading part in crushing a desperate rebellion by the serfs in 1573 led by Matija Gubec, which the Bishop terminated by arresting Gubec and crowning him with molten iron for his impertinence.

, to the status of patriarch, as it took a patriarch to crown an emperor. The Serbian Empire was short-lived, however, and scarcely outlasted Dušan’s death. Under his son, Uroš V, the tsardom dissolved into a patchwork of petty lordships. Uroš was driven from the throne in 1366 and, after his death in 1371, the royal house of Nemanja died out. Serbia by then was so divided that the most important Serbian princely ruler, Lazar, did not even claim the title of tsar but remained a mere knez. As in Croatia in the 1090s, the extinction of the native dynasty gave powerful neighbours the chance to invade. From the west, King Tvrtko of Bosnia claimed the throne of Serbia for himself. But the most serious threat came from the east. By 1386 Ottoman armies had overrun southern Macedonia and reached the city of Niš, north of Kosovo. Lazar attempted, too late, to reunite the Serbian factions against a common enemy. On 28 June 1389, Vidov Dan – St Vitus’ Day – Lazar’s army encountered Murat’s invaders on the undulating plain of Kosovo Polje. The Serbs were not alone, and counted a substantial number of Bosnians, Bulgars, Croats, Wallachians and Albanians in their ranks. In the battle that followed, Murat was killed along with Lazar. But the result was an Ottoman victory, which sounded the death knell of the Serbian state.

, to the status of patriarch, as it took a patriarch to crown an emperor. The Serbian Empire was short-lived, however, and scarcely outlasted Dušan’s death. Under his son, Uroš V, the tsardom dissolved into a patchwork of petty lordships. Uroš was driven from the throne in 1366 and, after his death in 1371, the royal house of Nemanja died out. Serbia by then was so divided that the most important Serbian princely ruler, Lazar, did not even claim the title of tsar but remained a mere knez. As in Croatia in the 1090s, the extinction of the native dynasty gave powerful neighbours the chance to invade. From the west, King Tvrtko of Bosnia claimed the throne of Serbia for himself. But the most serious threat came from the east. By 1386 Ottoman armies had overrun southern Macedonia and reached the city of Niš, north of Kosovo. Lazar attempted, too late, to reunite the Serbian factions against a common enemy. On 28 June 1389, Vidov Dan – St Vitus’ Day – Lazar’s army encountered Murat’s invaders on the undulating plain of Kosovo Polje. The Serbs were not alone, and counted a substantial number of Bosnians, Bulgars, Croats, Wallachians and Albanians in their ranks. In the battle that followed, Murat was killed along with Lazar. But the result was an Ottoman victory, which sounded the death knell of the Serbian state. ; from there he was dragged back to Jajce, on a promise he would not be harmed. Notwithstanding his pledge, Sultan Muhammed II had the King beheaded in his tent, outside Jajce. It was not quite the end of Christian Bosnia. In the 1460s the energetic King of Hungary–Croatia, Mathias I Corvinus (1458–90), turned back the tide and reoccupied large parts of northern and central Bosnia, including Jajce. In spite of this, the Ottomans continued to stream into Bosnia and Croatia as well, provoking desperate appeals from the Croat nobles for foreign support. Mathias Corvinus resented the Frankopan Lord of Krk’s request for Venetian support against the Turks and confiscated the Frankopans’ prize possession – the town of Senj. Fearing that the King planned to confiscate the island of Krk as well, the Frankopans surrendered it to Venice in 1480.

; from there he was dragged back to Jajce, on a promise he would not be harmed. Notwithstanding his pledge, Sultan Muhammed II had the King beheaded in his tent, outside Jajce. It was not quite the end of Christian Bosnia. In the 1460s the energetic King of Hungary–Croatia, Mathias I Corvinus (1458–90), turned back the tide and reoccupied large parts of northern and central Bosnia, including Jajce. In spite of this, the Ottomans continued to stream into Bosnia and Croatia as well, provoking desperate appeals from the Croat nobles for foreign support. Mathias Corvinus resented the Frankopan Lord of Krk’s request for Venetian support against the Turks and confiscated the Frankopans’ prize possession – the town of Senj. Fearing that the King planned to confiscate the island of Krk as well, the Frankopans surrendered it to Venice in 1480. azma, in western Slavonia, became too close to the Ottoman frontline. Osvald’s work was followed up by his successor, Luka Baratin, who used the legacy of 10,000 florins left by Osvald to continue work on the new fortifications. In 1510 the Bishop had to apply to Pope Julian II for permission to demolish the Church of St Emerika, which lay in the path of the proposed west-facing defences, in front of the cathedral. The Bishop told Rome of the urgent need to put up the fortifications, as the cathedral lay ‘near the land of the Turks who attack these regions with frequent incursions. It is to be feared that the church, if not secured by the erection of good defences, could in a short time be destroyed by the attacks of the said Turks.’

azma, in western Slavonia, became too close to the Ottoman frontline. Osvald’s work was followed up by his successor, Luka Baratin, who used the legacy of 10,000 florins left by Osvald to continue work on the new fortifications. In 1510 the Bishop had to apply to Pope Julian II for permission to demolish the Church of St Emerika, which lay in the path of the proposed west-facing defences, in front of the cathedral. The Bishop told Rome of the urgent need to put up the fortifications, as the cathedral lay ‘near the land of the Turks who attack these regions with frequent incursions. It is to be feared that the church, if not secured by the erection of good defences, could in a short time be destroyed by the attacks of the said Turks.’