4

Is This Place at Your Command?

Neil Young, Elliot Roberts, and David Briggs

He’s the Perfect Arranger

It was around the time that Buffalo Springfield was rapidly disintegrating as a band that Neil Young first met Elliot Roberts, the man who would eventually guide his career through the decades as his manager. The two of them were introduced by Joni Mitchell (who was already a Roberts client), when Mitchell and Young were recording in the same building and Joni insisted that Roberts had to meet Young, who according to Mitchell was “the funniest guy I know besides you.”

Upon meeting, Young and Roberts famously clicked to such a degree that Young even invited him to come live with him in the guest house of his Laurel Canyon home. However, Roberts’s first attempt at managing Young’s career (while he was still with Buffalo Springfield) wasn’t nearly so fortuitous, and ended with Young famously firing him.

As the story goes, Young had taken ill (between the pressures he was feeling within the band at the time and his ongoing epileptic condition, his fragile health issues were an ongoing concern back then) at a hotel while on the road with Buffalo Springfield. When he summoned Roberts for the purposes of locating a doctor, it was to no avail, because the man who would eventually go on to guide the business affairs of Neil Young for decades to come was otherwise occupied shooting off some golf balls at a driving range located near the hotel.

Upon finally locating Roberts, Young informed his would-be manager that his services would no longer be required—even though the two were more or less living under the same roof at the time. One can only imagine the levels of discomfort that existed between them in regard to that arrangement, particularly on Roberts’s end.

Still, Roberts, who at the time coveted the opportunity to manage the Buffalo Springfield—even as the group was falling apart—as a prize that was definitely worth fighting for, refused to give up.

In another of Roberts’s later bids to manage the Springfield, Young successfully (and by some accounts rather venomously) argued against it in the subsequently heated meetings between the band and their would-be new manager. Although Roberts has long since gained a well-earned reputation as one of the toughest negotiators in the music business, Young’s arguments in that meeting were so forceful that they reportedly reduced the normally tough-as-nails Roberts to tears.

But once Young left the band (permanently this time) and the Buffalo Springfield had finally split up for good, he went straight back to Elliot Roberts and asked him to manage his solo career, explaining his earlier arguments against it away by saying that this had been his true motive all along. In the typical Neil Young vernacular, he later explained the decision to go after Roberts by saying that “Elliot’s got soul.” Roberts’s own response upon learning of Young’s ulterior motives in sandbagging him with Buffalo Springfield was that the tactic reminded him of his former mentor, David Geffen.

Later on, Young would prove to be a strong Roberts ally in the bidding war over the management of what was then recognized as the biggest prize in all of rock ’n’ roll—the newly formed supergroup that had been dubbed the “American Beatles” by the rock press, Crosby, Stills and Nash—which Young himself had just joined (more on that in a later chapter of this book). Of course, Roberts’s association at the time with rising music biz hotshot David Geffen—who showed up with Roberts when he made his pitch to the band—didn’t exactly hurt his case either.

Born Elliot Rabinowitz, Roberts had been mentored by Geffen working in the mailroom at New York’s William Morris Agency (where, among other things, Geffen taught Roberts the art of things like steaming open the company mail and using the secrets contained within to one’s own personal advantage). Eventually, Roberts took on Native American folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie as a client, who in turn introduced him to then up-and-coming artist Joni Mitchell.

Depending on who is telling the story, Roberts has been described as both one of the most honest men in the record industry and one of its biggest liars. As Young’s longtime manager, Roberts has also often been as much a hired gun for the artist as he has been merely his advisor and confidant.

Truth be told, Elliot Roberts has probably spent as much time running interference and subsequently dodging bullets for the notoriously mercurial artist—with his often volatile nature and tendency to shift gears on a dime—as he has done anything else. More than anything, though, Roberts has been Neil Young’s most trusted ally, with the biggest key to their long relationship probably being his ability to simply let Neil be Neil.

In addition to building an impressive roster of artists for their own Lookout Management company, Roberts and Geffen would eventually form Asylum Records, the Warner Brothers–distributed label that would become most singularly associated with the Southern California singer-songwriter boom of the early seventies. Asylum’s artist roster was packed with the most successful names in the genre such as Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, and its biggest act, the Eagles.

With the help of producer Jack Nitzsche (who had already been talking up Young to Warner executives like Mo Ostin), Roberts also engineered the signing of Young as a solo artist to Warner Brothers imprint Reprise Records—the label he would call home for his entire career (with the exception of his tumultuous ten-year association with Geffen Records during the eighties).

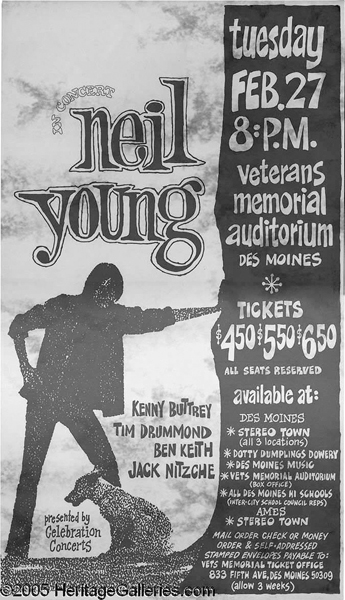

Concert poster from 1971 for Neil Young during the post-Crazy Horse “folk-pop” period (despite the earlier Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere cover art).

Courtesy Noah Fleisher/Heritage Auctions

Be on My Side, I’ll Be on Your Side

It was during the same period the Buffalo Springfield was imploding, around 1967, that Young also first encountered David Briggs.

Like so many Neil Young stories, this one begins with the artist hitchhiking. When Briggs, who was barreling down the highway in an army personnel carrier vehicle, decided to pick up the wayward hitchhiker, a bond began between the two men that would last decades and produce nearly twenty albums, including some of the most noteworthy albums of Young’s career. Like Stephen Stills before him, David Briggs would in fact become one of the most important figures in Young’s artistic life, and the two men would likewise share the same sort of love/hate relationship that ultimately bonded them like brothers.

Sharing a love of cars and music, Young also found a true kindred lunatic in Briggs. It’s no wonder that in much the same way he so often returns to work with his on-again, off-again garage-rock band Crazy Horse, Young likewise kept coming back to Briggs to produce his records.

It’s also probably no accident that Briggs has produced most of Young’s collaborations with the Horse. Briggs’s approach to recording rock ’n’ roll in fact shares much in common with the way that Crazy Horse plays it. In Jimmy McDonough’s Shakey, Briggs tells the author that he could teach him everything he knows about making records in an hour. He then goes on to explain his recording philosophy of just putting everyone in the room and letting them bang it out—preferably with the shortest, most direct line from the musicians playing in the room to the machines capturing the music on tape as possible.

Claiming that all of the advances in recording technology have destroyed the music business, Briggs is a firm proponent that “less is more.” One of his most famous quotes is that when it comes to rock ’n’ roll, “the more you think, the more you stink.”

Born in Casper, Wyoming, Manning Philander “David” Briggs was a rock-’n’-roll fan early on, as well as a frustrated musician who ended up making records for other artists once he determined he couldn’t play very well. As a teenager, Briggs also had a taste for fast cars, and ran with a local car club/youth gang called the Vaccaros. After producing his first record (for comedian Murray Roman), Briggs ended up going to work for Bill Cosby’s Tetragrammaton Records.

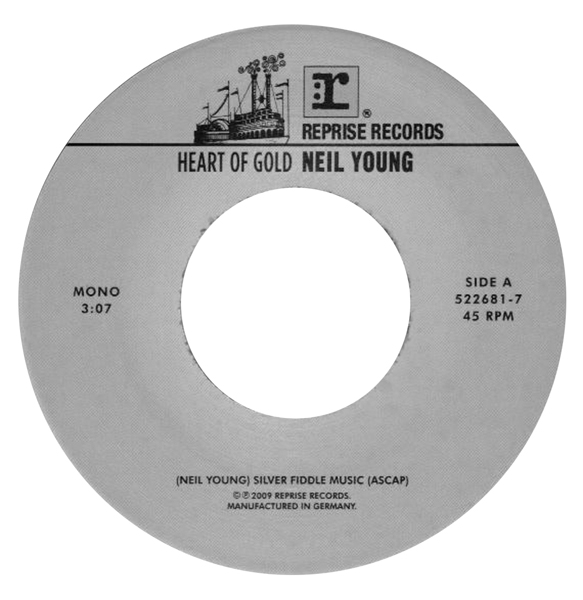

Original Reprise 45 for the #1 smash “Heart of Gold.”

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

Although his own legacy as a producer has become inextricably tied to his work with Neil Young, Briggs has also produced albums for Spirit, Alice Cooper, Nick Cave, and others and has played on sessions for a number of notable artists. David Briggs passed away in 1995 following a battle with lung cancer.

Often referred to as the unofficial fifth member of Crazy Horse, Briggs also worked with a number of artists more closely associated with Neil Young—most notably guitarist, one-time Crazy Horse member, and subsequent Young sideman Nils Lofgren and his band Grin in the sixties and early seventies.

Briggs’s long professional association Neil Young ended with 1994’s Sleeps with Angels (although much of their work together can also be heard on the Archives box set). But it was on Young’s self-titled 1968 debut solo album that their long-standing personal and artistic partnership would first bear fruit.

I’ve Been Waiting for You, and You’ve Been Coming to Me

Once he was free of the Buffalo Springfield, Young was likewise determined to free himself of the artistic constraints he had previously felt within that band, and to do things his own way as a solo artist this time around. By most accounts, he had also become something of a new man as a result of this newfound freedom.

In fact, he not only seemed much less frail and sickly than he had been in the past (the epileptic seizures that had often been brought on by the stressful conditions he felt within Buffalo Springfield had become far less frequent by then), but there also seemed to be a new air of strength and confidence about him.

Perhaps for the first time since his arrival in Los Angeles driving a refurbished Pontiac Hearse, Young seemed truly grounded. At long last, he seemed to be becoming not only his own artist, but his own man as well.

For his first album as a solo artist, Elliot Roberts had negotiated a unique contract with the Warner Brothers’ label Reprise (whose flagship artist had been none other than Frank Sinatra). Under the terms Roberts negotiated on his behalf, Young took a much smaller upfront advance than the industry norm at the time in exchange for a higher royalty rate (or “points” in the record industry vernacular) later for his future recordings. Although this may have seemed an ill-advised move (Young was still solidly in the “starving artist” category at the time), it would later on prove to be a brilliant one on Roberts’s part, and one that would produce lasting dividends and financial security for his artist.

Although the advance was smaller than the standard for other artists at the time, it was still significant enough for Young to make a down payment on a brand new home for himself in the notorious hippie community that was L.A.’s Topanga Canyon neighborhood.

Situated in the Santa Monica Mountains between L.A. and Malibu, the Topanga Canyon of the sixties was something of an idyllic artists’ enclave—actually a “hippie haven” would probably be a better term—populated by a bizarre mix of outlaw bikers, musicians, and other assorted long-hairs and counterculture types. Neil’s newfound neighbors at the time included such notables as actor Dean Stockwell, a fellow music freak and an early and vocal fan of Young’s—who would eventually introduce the artist to new-wavers Devo in the late seventies—inspiring both Young’s Human Highway film and his groundbreaking Rust Never Sleeps album in the process.

Picture sleeve 45 of CSN&Y’s Joni Mitchell cover “Woodstock” backed with Neil Young’s “Helpless.”

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

The atmosphere in Topanga was likewise typical of the sixties counterculture. Drugs and music were the driving force of the day, and by this time Young had become an avid marijuana smoker himself, which some of those around him saw as a sign of his newfound confidence (Young had previously been regarded as something of a lightweight when it came to pot and other drugs—perhaps because of his other fragile health issues—even as nearly everyone else around him indulged themselves both freely and, according to most accounts, quite often).

With the impromptu jam sessions that were coming out of the Topanga scene on a near nightly basis—not to mention the rather abundant drugs and sex that came along with them—came the inevitable string of bizarre and colorful counterculture characters that would pass through this community.

At one such juncture, Young would even end up rubbing shoulders with future mass murderer Charles Manson. At that time an aspiring musician himself, Manson’s path crossed Young’s through a mutual acquaintance with Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson.

With “Squeaky” Fromme and the rest of the ever-present “Manson Girls” always in tow behind their charismatic guru in various combinations whenever he showed up in Topanga, Young was also fascinated by their eerie devotion to him. “They looked right through the rest of us,” Young has since said of the odd meetings with the future architect of one of history’s most infamous mass murder sprees.

Young was nonetheless actually impressed enough with Manson’s music to talk him up to Warner Brothers executives like Mo Ostin. Young once described Manson to Ostin and the Warner brass as “similar to Dylan” and that “he just makes this stuff up as he goes.” Young has since also remarked that Manson’s ultimate rejection by the record industry was what his crime spree was really all about.

It was as part of this same odd community of hippies, bikers, and freaks in Topanga Canyon that Young would also meet his first wife, Susan Acevedo.

According to most accounts, Acevedo—whom he met at the Canyon Kitchen diner she ran—functioned as equal parts personal manager and surrogate mother figure. She has been described by some as a “Rassy” type figure (referring to Young’s own mother)—strong-willed, organized to a fault, very protective of her loved ones, and of her husband in particular.

Young’s first solo album, released as the year 1968 ended and 1969 began, was, in record-industry lingo, a “stiff.”

Not that the self-titled album doesn’t have its share of gems—tracks like “The Old Laughing Lady” and especially “The Loner” have certainly stood the test of time in the decades since the album’s original release. But at the time it first came out, Young’s solo debut just didn’t quite set the rock music world on fire in the way its creators had probably hoped for.

Produced by David Briggs, with some help from Jack Nitzsche (who had also helped craft the symphonic layers of Young’s latter-day Springfield songs “Expecting to Fly” and “Broken Arrow”), much of the album is recorded with that same multilayered approach. The album was also recorded using studio musicians like latter-day Springfield bandmate Jim Messina and guitarist Ry Cooder (who is said to have somewhat thumbed his nose at Neil Young as a musician).

“I should have just left it alone,” Young has been quoted as saying in interviews in the years since, speaking of the album’s many recording studio tweaks and overdubbed tracks. Young has also said that he is nonetheless thankful that he learned from the experience and has since gotten the tendency to “over-record” well out of his system—something that would become readily apparent on his very next album, recorded with his newly christened band Crazy Horse.

Another factor that almost certainly affected the poor sales showing of Young’s solo debut is the album cover. A painting of Young by Topanga artist Ron Diehl, the bizarre portrait featured Young’s face with the buildings of L.A. coming up across his chest on the bottom, set against a backdrop of flaming mountains.

Most notably, the album cover didn’t even have Neil Young’s name on it, at least not on the original jacket. This was corrected on a second pressing of the album—which also cleaned up some of the more excessively overdubbed tracks.

But the commercial damage had already been done.

Rare four-track CSN&Y single combining tracks from Déjà Vu with the “Ohio” single.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection