5

When I Saw Those Thrashers Rolling By

Neil Young and Crazy Horse

Neil Young has been quoted as saying, “If I played Crazy Horse tours every tour, I’d be dead.”

Perhaps this at least partially helps explain his long-standing, on-again, off-again association with the group that has been described as “the third best garage band in the world” (by legendary concert promoter Bill Graham) and as “the American Rolling Stones” (by Young himself).

On the song “Thrasher” from his classic Rust Never Sleeps album (one of the many records Neil Young has made with Crazy Horse), some fans believe the song lyrics “So I got bored and left them there, they were just deadweight to me,” refer to Neil Young’s often contentious relationship with Crosby, Stills and Nash, and specifically to one of the many times he left that group over the years, usually over artistic differences. But in the very same song, when Young sings “When I saw those thrashers rolling by, looking more than two lanes wide, I was feelin’ like my day had just begun,” he could just as easily be referring to Crazy Horse.

“They’re primitive, but they’ve got soul,” Young has said of Crazy Horse. And when Neil Young says somebody “has got soul,” it is high praise indeed.

Down in Hollywood, We Played So Good

Dating back to 1969’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, whenever Young wants to crank Old Black up to eleven and let it thrash, his band of choice has nearly always been none other than the mighty Horse. Although they sometimes have to wait years in between projects, Crazy Horse is also the band that has enjoyed the longest working relationship with the mercurial Young.

Twelve of the albums in Young’s vast catalog—beginning with Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, continuing through classics like Rust Never Sleeps and Ragged Glory, and ending with 2003’s Greendale—are officially attributed to Neil Young and Crazy Horse. At least five others, including such albums as Tonight’s the Night, Zuma, and American Stars and Bars prominently feature various members of the group. Although Crazy Horse are not officially billed on the album covers, it is common knowledge that the band are prominently featured on several cuts. These are, at least in part, Neil Young and Crazy Horse records.

How could albums that feature songs like “Tonight’s the Night,” “Like a Hurricane,” and “Cortez the Killer” be anything but?

On a number of Young’s other recordings, such as Comes a Time and Are You Passionate?, the Horse likewise played a significant role in their creation. But for various reasons their involvement was cut short.

In the case of the former, Young somewhat uncharacteristically uses Crazy Horse on the softer-sounding folk-rock songs of that album like “Lotta Love.” The latter began as a Crazy Horse project but later took a left turn when he decided he wanted to pursue a more R&B feel and used members of Booker T. and the MGs and other studio musicians instead. Hey, nobody ever said working with Neil Young was easy.

One thing’s for sure, when it comes to Crazy Horse there is no middle ground—you either love them or you hate them (David Crosby has been among the more vocal of the Horse’s many detractors).

Full Moon and a Jumpin’ Tune

When Neil Young first began playing with Crazy Horse in 1968, he didn’t so much put together the group as he did steal them.

Crazy Horse actually began life as a vocal group based out of Columbus, Georgia, called Danny and the Memories (named after its then lead singer, future guitarist and ultimate rock-’n’-roll tragedy Danny Whitten).

Moving out west to San Francisco at the height of the hippie movement centered there, the band briefly changed its name to the Psyrcle and moved into a more psychedelic direction, releasing a record produced by Sly Stone (who was at the time a popular local DJ, prior to enjoying his own rock star success—and accompanying excess—with Sly and the Family Stone).

The group eventually wound up in Los Angeles, and by now had expanded to a seven-piece band featuring three guitarists, along with drums, bass, and an electric violinist. They called themselves the Rockets. Although Whitten was now playing guitar, it was his singing voice that seemed to draw the most attention. When Danny Hutton was first putting together his concept of a band fronted by three vocalists (who would later become very successful as the late sixties pop group Three Dog Night), Whitten was among the vocalists being considered for one of the three slots.

Young also became a fan of the Rockets, and began to join the group for informal jam sessions at their Laurel Canyon “Rockets Headquarters.” At Whitten’s invitation, Young also joined the band onstage during a gig at the Whisky A Go-Go, where his incendiary guitar work with Old Black blew everyone away and left original Rockets guitarist George Whitsell in the dust.

With Young already looking ahead to a more straightforward approach for his next record—following all of the overdubs and studio tinkering that had plagued his solo debut—he invited three members of the Rockets (Whitten, bassist Billy Talbot, and drummer Ralph Molina) to join him for a preliminary jam session in Topanga Canyon.

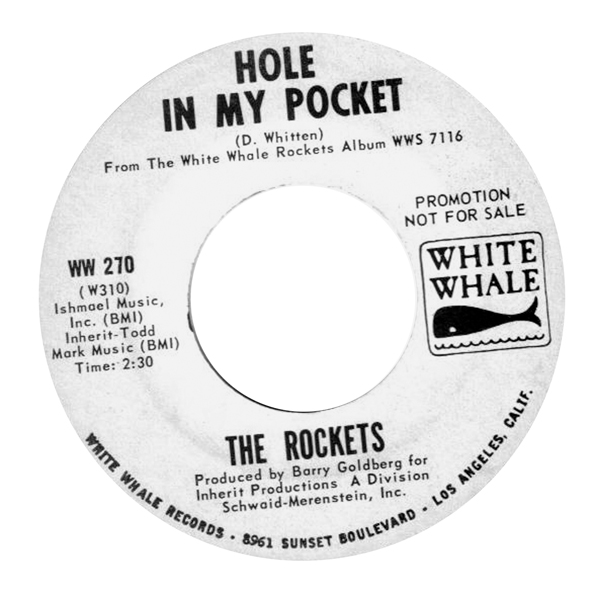

Original pre-Crazy Horse single by the Rockets on White Whale Records (also home to the Turtles). “Hole in My Pocket” was written by Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten, who later died a tragic premature death the same day he was fired from the Harvest tour by Neil Young.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

And that is the story of how Neil Young stole the Rockets in order to create the longest-lasting and most durable of his many bands, Crazy Horse.

Has Your Band Begun to Rust?

While no one would ever accuse Crazy Horse of being virtuoso musicians—David Crosby has summed up his opinion of the band on more than one occasion by simply saying “they can’t play”—there is little doubt that the sum of their individual parts creates a more perfect whole. The Horse are capable of locking into a very effective, if occasionally sloppy and loose groove whenever called upon to do so, like no other band Neil Young was worked with. In short, they fit Neil Young like a glove.

From “Down by the River” to “Cortez the Killer” to “Love and Only Love,” Crazy Horse have also proven themselves time and time again to be the best vehicle—perhaps the only vehicle, really—for those times when Young feels the need to shred on those trademark extended, hypnotic guitar solos. Indeed, these lengthy—and loud!—sonic explorations have become as much a signature of his sound as the lusher-sounding folk-pop of albums like Harvest.

Nowhere, is this more apparent than on his second solo album—and his first with Crazy Horse—1969’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

In sharp contrast to the tentativeness of his self-titled solo debut, this is the sound of an artist who has at long last found his true musical calling, and of a band responding to it by firing on all cylinders and locking into an absolutely magical groove throughout. With Crazy Horse behind him, Neil Young’s second album was the first of what would be many truly great ones.

Purple Words on a Grey Background

The two centerpieces of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere are also its two longest songs, “Down by the River” and “Cowgirl in the Sand.”

With each of these songs, Neil established a template that would serve him quite well many times over in the years and decades to come. Both of these songs are more like sonic pictures, really. Clocking in at roughly nine and ten minutes long respectively, the songs show Neil Young and Crazy Horse turning the idea of the guitar solo as an instrumental break completely inside out.

In both instances, it is in fact Neil’s vocals that serve as the brief breaks between the extended washes of guitar and feedback that dominate these two amazing songs. Both songs also marked the formal recorded introduction to the world of Old Black—the 1953 black Les Paul Neil Young purchased for fifty bucks from Jim Messina, and that has since become Neil’s axe of choice when the job calls for that little extra something that is both dirty and loud.

Amazingly, both songs, along with the album’s single “Cinnamon Girl,” were written in a single day while Neil Young was sick and running a 103-degree fever. There has been ample speculation throughout the years over just who the subject of “Cinnamon Girl” was, with many stepping forward to claim credit for being the song’s inspiration.

I Could Be Happy the Rest of My Life

One of the more credible stories we’ve come across can be found in a March 7, 2010, post on the Neil Young news site Thrasher’s Wheat. In the article, an unidentified woman who was a high school student at the time in 1968 claims to have met the rock star in front of the Riverboat, a Toronto coffee house where Young was scheduled to play a gig that night. Spotting his guitar case, the then fifteen-year-old used an opening line about interviewing musicians to be her boyfriend. Young took the bait, replying “what’s involved?”

Our “Cinnamon Girl” picks up the story from there:

I said “You get to hang around with me for a couple of hours. I will ask you questions about dating and relationships and see if you pass. There will be kissing involved … are you a good kisser?”

Neil said “I guess so.”

He seemed to be a little shy but amused by the situation. He didn’t seem to be in any hurry to go anywhere and so the game started. When we were together that night, I asked Neil to write a happy song about me and he promised he would. My nickname at school was “The Cinnamon Girl.”

The brief relationship ended when the “Cinnamon Girl” failed to meet Young at the Riverboat because she had taken sick. Interestingly, Young also became ill around this time, famously writing the songs “Down by the River,” “Cowgirl in the Sand,” and of course “Cinnamon Girl” in a single afternoon while nursing his fever. Coincidence? Not according to the alleged “Cinnamon Girl” herself:

Reprise Records pressing of the Crazy Horse “solo” 45 “All Alone Now” written by original Crazy Horse member George Whitsell.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

“I think ‘Cowgirl in the Sand’ is also about me,” she says today. “When we first met I was playing a crazy game with him, and he seemed amused by it. We talked about horseback riding, getting a farm one day, and the fact that I wouldn’t tell him my age. I turned the conversation to the ages girls could wed in different provinces yet couldn’t drink or vote. We spent the night in a park on the edge of a kid’s sandbox talking about our lives, our dreams, and the urgency for him to get to California.”

The coincidences are intriguing. On his Thrasher’s Wheat website, Young superfan Thrasher connects the dots this way: “Down by the River (boat)”; he shot his baby (broke up with his young girlfriend); a red head (“Cinnamon Girl”); who was a “Cowgirl (hippie) in the Sand (box at the park).”

Thrasher concludes this weaving of parallel lines with the simple observation: “you just never know.” We tend to agree.

On “Cinnamon Girl,” the tight, compact rocker that chugs along to a funky groove courtesy of Talbot and Molina, Young sings that he is “a dreamer of pictures.” With Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, he paints these sonic pictures with all the mastery of an artist who has truly perfected his craft.

The record-buying public likewise responded.

“Cinnamon Girl” became a modest hit as a single, and is also notable for its infamous guitar solo, which essentially is structured around the repetitive use of a single note. But it was mainly the FM progressive rock airplay of “Cowgirl in the Sand” and “Down by the River” that most helped Everybody Knows This is Nowhere become Neil Young’s first hit on the Billboard albums chart, where it peaked at #34.

Buddy Miles, best known at the time as the drummer with both Mike Bloomfield’s Electric Flag and Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys, would also score a hit in 1970 with a cover of “Down by the River” on his own solo album Them Changes.

Sea of Madness

In the meantime, Stephen Stills, Young’s former bandmate in Buffalo Springfield, had a hit of his own on his hands with the debut album from Crosby, Stills, and Nash, his newly formed supergroup with former Byrds member David Crosby and ex-Hollies member Graham Nash.

On the strength of songs like Stills’s “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” (his emotional outpouring of romantic emotion to his girlfriend, folksinger Judy Collins) and Nash’s pop hit “Marrakesh Express,” CSN’s debut had become a megahit. The only problem was, Stills had produced and played nearly everything on the album (save for the vocals), and the “band” needed to tour the record.

Although Young was reluctant at first to sign on (and both Stills and Nash had their own doubts as well), Elliot Roberts (who was by now managing both Young and CSN) engineered a deal that amounted to the sort of offer Young simply couldn’t refuse. Under the arrangement, Young would become a full one-fourth musical, creative, and financial partner in the newly christened Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, and he would be able to pursue his projects as a solo artist and with Crazy Horse at the same time.

Young’s relationship with his new partners in the “American Beatles” would prove to have more than its share of ups and downs over the years—the schism between them became immediately and readily apparent by the time of the band’s second gig at Woodstock, where Young refused to be filmed for CSN&Y’s spot in the movie documenting the historic festival.

But at the time, the decision to complete CSN&Y was probably the right one for Young. With his own star already on the rise, Young’s membership in America’s hottest band at the time would pay its own dividends and eventually help launch him to superstardom, first breaking his 1970 album After the Gold Rush into Billboard’s top ten and finally landing Young his first #1 album as a solo artist with Harvest.

The Needle and the Damage Done

Crazy Horse in the meantime would be put on the first of what would become several decades of holding patterns between Neil Young projects, where the band’s services would only become required as needed.

Young did briefly use Crazy Horse on the early sessions for what became the After the Gold Rush album, but later ended up firing the band when, among other issues, it became apparent that guitarist Danny Whitten’s drug problems were becoming an increasing liability. Neil Young and Crazy Horse had played a handful of concert dates in 1970 (including a great show at the Fillmore East, which has since been captured for posterity on Neil Young’s Archives Vol. 1). But eventually, Whitten’s inability to hold it together became impossible to overlook when he began nodding out onstage right in the middle of the group’s performances.

Radio station promo single for “One Thing I Love” by Crazy Horse.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

If Young’s membership in CSN&Y had put any idea of Neil Young and Crazy Horse as a long-term proposition on hold—establishing a pattern that continues to this day—Whitten’s drug problems only served to further complicate the situation. In the end, Whitten’s condition worsened to such a degree that he was eventually fired altogether from Crazy Horse—the band he had created—by the rest of the group. About a year later, Whitten was found dead of a drug overdose after being fired from the guitar spot on the Harvest tour by Young earlier the same day.

Arguments can be—and have certainly been—made about the effect Whitten’s death left on Young’s own psyche over the years, as well as on his long-term, on-again, off-again relationship with the Horse. What is known for sure is that the lingering feelings of guilt over Whitten’s death, along with other issues, played heavily enough on Young to cast a shadow of doom over what should have been the most triumphant tour of his career.

Instead, the Harvest tour found Young in an often surly mood both on- and offstage, while audiences who had come to hear the mellow folk-rock of his #1 megahit album were instead subjected to the darker, moodier new songs eventually documented on the live Times Fade Away album.

Guitarist Danny Whitten’s heroin addiction and resulting death had left a deep enough mark on Young that his next several albums would take a sharp turn toward a darker new direction that Young himself has since described as “the ditch.” Of the three albums that make up what fans now commonly refer to as the Ditch Trilogy, 1975’s Tonight’s the Night is the most direct response to the drug-related deaths of both Whitten and CSN&Y roadie Bruce Berry, who also became a casualty of drugs during the same period.

For their own part, the members of Crazy Horse seemed to have taken having their careers as Neil Young’s band being put on hold mostly in stride over the years.

In 1971, they recruited young guitar prodigy Nils Lofgren (who also played on Young’s After the Gold Rush) and producer Jack Nitzsche (doing double duty as the band’s “fifth member” on keyboards) and released a “solo album” of their own without Young. Although the album sold poorly, it is notable for the inclusion of songs like “Dance, Dance, Dance” and “(Baby Let’s Go) Downtown”—both of which would later prove to be significant entries in the Neil Young canon.

Whitten’s guitar slot was eventually filled for good by Frank “Poncho” Sampedro, a guitarist Billy Talbot met in Mexico. In addition to Crazy Horse, Sampedro went on to play with several of Neil Young’s bands, including the Bluenotes and the Restless.