6

Departed Bandmates, Brothers in Arms, and Sisters in Song

What follows is a short list of musicians, collaborators, and otherwise significant supporting players who, over the course of Neil Young’s long career, have played significant roles and who have since passed on.

This is not intended as a complete list by any means, but rather as a short overview of some of Young’s most important musical partners in crime over the years, who were taken away far too soon and without whom many of his greatest artistic achievements would not have been possible.

Carrie Snodgress—Actress/Girlfriend

Although this chapter is primarily devoted to the artists and musicians who played significant roles in Young’s career and who have since passed on, it would be a major omission not to include actress Carrie Snodgress on the list.

As far as I know, Carrie Snodgress has never sung or played a single note on a Neil Young album or performed with him onstage. But there is no question that she was a major influence on his songwriting—particularly during his most commercially successful period.

Several of the songs on Young’s smash 1972 album Harvest were undeniably inspired by the actress he had fallen deeply in love with—most notably “Heart of Gold” and “A Man Needs a Maid.”

At one point prior to the release of Harvest, Young had even taken to performing the two songs together as a suite (this can be heard on the Archives Performance Series release Live at Massey Hall 1971). A number of songs on subsequent releases were likewise inspired by his relationship with Snodgress, including “Motion Pictures” from On the Beach (which is even dedicated to her on the original album sleeve) and “New Mama” from Tonight’s the Night.

In the song “A Man Needs a Maid,” Young even describes how they met in lyrics like “I fell in love with the actress, she played a part that I could understand.” After seeing Carrie Snodgress in the movie Diary of a Mad Housewife with roadie Guillermo Giachetti, Young dispatched him to arrange a meeting—which eventually took place in a hospital room where Young was nursing back problems.

After the two of them fell in love, Snodgress effectively turned her back on her then quite promising movie career (this was coming off of an Oscar nomination for her Diary of a Mad Housewife role) to take up permanent residence at Young’s Broken Arrow ranch. Their son Zeke (who, like Neil’s other son Ben with present wife Pegi, is afflicted with cerebral palsy) was born in September 1972.

After the two broke up, Snodgress eventually resumed her movie career, although it never quite regained the luster of her brief glory days as a Golden Globe winner and Academy Award nominee.

Carrie Snodgress died on April 1, 2004, at the age of fifty-seven of heart failure as she was awaiting a liver transplant.

Danny Whitten—Guitar, Vocals (Crazy Horse)

Danny Whitten was the brilliant but troubled guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter who (along with Neil Young himself) was responsible for the two-pronged guitar attack heard on “Down by the River” and “Cowgirl in the Sand” (from the classic Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere album—Neil Young’s first recordings with Crazy Horse).

Although acknowledged by virtually everyone who has ever heard him as a brilliant musician with infinite rock-star potential—keyboardist and producer Jack Nitzsche once famously called him “the only black musician in Crazy Horse” in reference to his natural musical ability—some have also suggested that Whitten felt overshadowed by Neil Young in what had once been his own band, Crazy Horse.

But Whitten also had a darker side, which was most noticeably reflected in his heavy drug use. As early as 1970, his increasing addiction to heroin and other drugs had become an ongoing concern affecting both Young and the rest of Crazy Horse.

Things finally came to a head when, among other things, Whitten began nodding off during recording sessions and even onstage during the band’s concerts. This led to Young eventually firing Whitten and the rest of Crazy Horse (save for drummer Ralph Molina) during the sessions for Young’s third solo album After the Gold Rush.

Whitten was eventually asked to leave Crazy Horse altogether in 1972 by the rest of the band, who were by this time making albums on their own in addition to their higher-profile gig sometimes backing Neil Young. Whitten, the one-time leader of Crazy Horse, had become the band’s biggest liability.

Danny Whitten died of a drug overdose in Los Angeles on November 18, 1972, shortly after being fired by Young earlier the very same day. Whitten was just twenty-nine years old.

Despite Whitten’s drug problems, Young had decided to give him one final chance when he offered the guitarist a slot in the Stray Gators, the new band Young had assembled for a huge American arena tour booked to promote the 1972 #1 smash album Harvest. When the guitarist “wasn’t cutting it” (as Young would later recall) during rehearsals for the tour, Whitten was given fifty dollars and a one-way plane ticket to L.A., and told to go back home. He was pronounced dead in Los Angeles later that night, apparently overdosing on a lethal cocktail of alcohol and Valium.

It’s been said that upon receiving the news of Whitten’s death, Neil Young blamed himself for some time afterwards. What’s absolutely certain is that a significant number of his subsequent songs including “The Needle and the Damage Done” and those making up the album Tonight’s the Night were at least partially inspired by Whitten’s death (as well as another recent drug overdose casualty in the Neil Young camp, that of roadie Bruce Berry).

Of Whitten’s own songs, the best known is probably “(Come On Baby Let’s Go) Downtown,” a song about scoring heroin he co-wrote with Neil Young, and that he eerily sings posthumously on the Tonight’s the Night album. Another of Whitten’s best-known songs, “I Don’t Want to Talk About It,” has been famously covered by Rod Stewart and others.

Bruce Berry—Roadie

Bruce Berry is probably best known today as the guy immortalized as the “working man who used to load that Ford Econoline,” “sing a song in a shaky voice,” and “sleep until the afternoon” on the title track from Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night album.

He is also the very same guy his close friend Richard O’Connell found dead on June 7, 1973. Although the body was discovered by O’Connell on June 7, Berry had most likely died days three earlier on June 4—overdosing on a particularly lethal mixture of heroin and cocaine.

“’Cause people let me tell you, it sent a chill up and down my spine,” Young sings on Tonight’s the Night. “When I picked up the telephone, and heard that he’d died out on the mainline.” The words sound as darkly chilling now as they must have felt when he first wrote them.

It was likely Berry’s family connections with brothers Jan and Ken that got him the gig as a roadie with Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young in the first place. Brother Jan was one-half of the chart-topping surf-rock duo Jan and Dean, while Ken owned and operated Studio Instrument Rentals, a very successful rehearsal space and gear shop favored by a number of the top Los Angeles–based rock bands of the day, including CSN&Y.

When Bruce began working with S.I.R. as a teenager, he also brought his pals McConnell and Guillermo Giachetti along for the ride. Before long, Berry was working on the road crew for CSN&Y, reaping all the usual benefits of drugs and girls you’d expect, while loading equipment in and out of the very same Ford Econoline Van later made famous by the Neil Young song that prematurely eulogizes him.

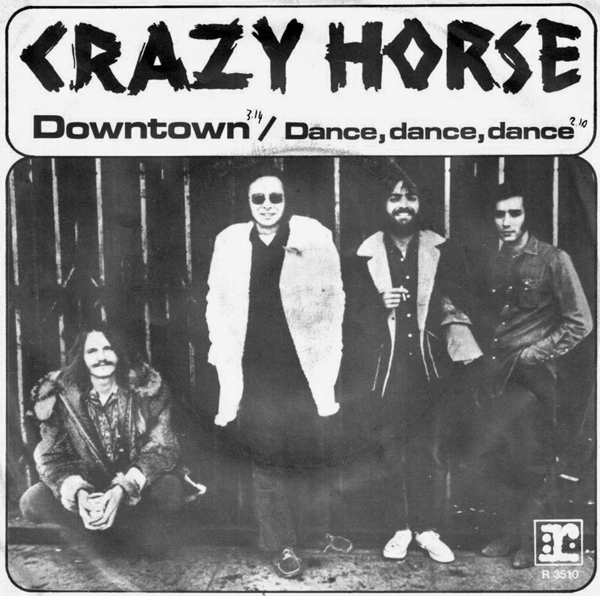

Picture sleeve of the Crazy Horse single for “Downtown” and “Dance, Dance, Dance.” Crazy Horse founder Danny Whitten’s life was tragically cut short by a drug overdose.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

As their confidence in the likable young man grew, Berry’s duties eventually grew to include procuring drugs for some of the other musicians and roadies in the CSN&Y camp—which at one point got him into considerable trouble with Crosby and Nash when he showed up with cocaine at a 1973 CSN&Y band meeting in Hawaii.

It seemed that the meeting had at least been partially called for the distinct purpose of convincing Young that Stills’s drug problems were reasonably under control, and that things would be just fine for an upcoming proposed CSN&Y tour. Crosby and Nash were said to have been furious when Berry crashed the botched “intervention” carrying his usual supply. Young himself decided afterwards that he wanted no part of it.

Even so, both Crosby and Stills continued to engage in drug-related activities with Berry, although the roadie was by most accounts actually introduced to heroin (somewhat ironically) by Young’s partner in Crazy Horse, Danny Whitten. By the time Berry returned to America from an extended overseas stay with Stills in England, he was a full-fledged junkie—even going so far as to allegedly steal one of Crosby’s guitars and sell it for drugs.

Berry’s death by drug overdose, coming just months after Danny Whitten had likewise been taken by the “white lady,” shook Neil Young to his core.

Not long afterwards, Young pulled out of the latest attempt at a projected new Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young record—which no doubt considerably pissed off his CSN&Y bandmates—and instead devoted himself to making the album recorded at Ken Berry’s Studio Instrument Rentals space that eventually emerged in 1975 as the dark, druggy masterpiece Tonight’s the Night.

Comrie Smith—Rhythm Guitar, Banjo

Comrie Smith was Neil Young’s grammar school buddy in Canada, as well as his one of his earliest musical accomplices. Long before he met the likes of Stephen Stills, or before there was ever a Buffalo Springfield, a CSN&Y, a Crazy Horse, or a Stray Gators, Young recorded some of his earliest original songs with his close friend Comrie Smith.

Like Young himself, Smith was heavily influenced by Canadian folk artists like Ian and Sylvia very early on, and the two budding young musicians soon bonded over this shared passion.

Together, Young and Smith cut several folk-influenced sides back in the early days using little else but a reel-to-reel recorder, Young’s “Dylan kit” of a guitar and a harmonica, and Smith’s banjo. They were recorded in the unlikely setting of an attic at their old school, Lawrence Park.

On these makeshift recordings, including such early original Neil Young originals as the folk-influenced “Casting Me Away from You,” and “There Goes My Babe,” as well as the more raucous-sounding, R&B-influenced rave-up “Hello Lonely Woman,” one can already hear the two most recognizable elements in the duality of the Young sound we’ve come to know today. Even back then, Young was as comfortably adept at thoughtful, sensitive songwriting as he was at rocking the house (or, in this case, at least the school attic).

Fortunately, these early recordings with Comrie Smith survive today, and can be heard on Young’s Archives Vol. 1 boxed set. Smith passed away due to complications from heart failure on December 11, 2009. He was sixty-four years old.

Rufus Thibodeaux—Fiddle

Fiddle player Rufus Thibodeaux first began recording with Young on his Comes a Time album, but more notably was later part of the International Harvesters, the band Young assembled for his country-flavored album Old Ways. Thibodeaux can also be heard on Young’s 1980 album Hawks and Doves.

Revered in Nashville as both a Cajun and country fiddler of the highest order, Thibodeaux’s resume reads a who’s who of country music legends—from Bob Wills and Jim Reeves to Lefty Frizell and George Jones. Along with musicians like Floyd Cramer and the late, great Chet Atkins, Thibodeaux was considered by most of his peers and fellow country music associates in Nashville and elsewhere as simply the very best at what he did.

Much like Ben Keith, Thibodeaux also became one of Neil Young’s “go-to guys” during Young’s occasional left turns away from harder rock and more toward folk- and country-influenced “singer-songwriter” records.

Rufus Thibodeaux died peacefully on August 12, 2005. Although he had been in declining health, due largely to complications from diabetes, Thibodeaux remained active, continuing to make music right up until the end of his life.

Jack Nitzsche—Keyboards, Producer

Although he is remembered today mostly for his work with Neil Young, Jack Nitzsche already had a pretty impressive resume as a composer, producer, and arranger before the two of them ever met. A true musical renaissance man, Nitzsche either wrote or co-wrote hits ranging from the Searchers’ “Needles and Pins” to “Up Where We Belong” (from the film An Officer and a Gentleman).

Nitzsche also worked with Phil Spector, helping to craft the producer’s legendary “Wall of Sound” on such landmark recordings as Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep, Mountain High.” He later helped develop the keyboard sound heard on such early Rolling Stones singles as “Paint It Black.”

A naturally gifted keyboardist, Nitzsche was also a member of the legendary group of all-star L.A. session musicians known as the Wrecking Crew, along with people like drummer Hal Blaine, keyboardist Leon Russell, and guitarist Glenn Campbell—playing on numerous pop single hits by groups ranging from the Beach Boys to the Monkees during the sixties. Nitzsche has also either scored outright or contributed to the soundtracks for a very impressive number of films including The Exorcist, Stand By Me, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Nitzsche’s professional relationship with Young began when he produced the groundbreaking songs “Expecting to Fly” and “Broken Arrow” for Buffalo Springfield. Essentially Neil Young solo recordings, at the time both were still seen as a bold artistic step forward for the Springfield (particularly the former), and they continue to hold up very well today. From there, Nitzsche also co-produced Young’s solo debut (with David Briggs), although the results there were far less spectacular.

Even so, Nitzsche maintained a long and often contentious relationship with Neil Young over the years, performing both with Crazy Horse and on the artist’s more commercial albums such as Harvest.

Although Young has long since said that his brutal honesty was one of the qualities he admired most about Nitzsche, this was probably not always the case. The two of them have feuded both often and publicly, most famously in a 1974 interview with Crawdaddy! magazine, where among other things, Nitzsche criticized Young’s lyrics (“His lyrics are so dumb and pretentious”) and his guitar playing (“Everyone in the band was bored to death with those terrible guitar solos”).

Nitzsche has also gone back and forth many times on the subject of Crazy Horse, calling them “the American Rolling Stones” in one breath and lambasting their musical limitations and lack of professionalism in the next (“Whatever clothes they woke up in, that’s what they wear on stage”).

Despite their often acrimonious relationship (Nitzsche even eventually took up with Young’s former girlfriend, actress Carrie Snodgress), the two continued their on-again, off-again working relationship, striking gold together once again on Young’s 1992 album Harvest Moon.

Jack Nitzsche passed away of a heart attack at the age of sixty-three on August 25, 2000.

Bruce Palmer—Bass (Buffalo Springfield, Trans Band)

Praised by both Neil Young and Stephen Stills as one of the best guitarists either man has ever had the pleasure to play with, Bruce Palmer would still never again fully reclaim the rock-star glory he had once briefly experienced as bassist for the Buffalo Springfield.

Replaced in that band after his drug problems began to catch up with him by Jim Messina during the group’s final months, Palmer was briefly considered for the bass part in Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, only to be passed over in favor of the much younger Greg Reeves. In 1971, Palmer also released a solo album for Verve Records titled The Cycle Is Complete.

Years later, in 1982, Young once again tapped Palmer for the bass slot in the Trans Band, where he soon became a source of considerable frustration both to band members like Nils Lofgren and to Young himself. At one particularly volatile point, this even caused Young to come to blows with him during a heated band meeting in a hotel room. Although Young never actually fired him from the band, Palmer’s alcohol abuse while on an already chaotic European tour plagued with technical problems nonetheless eventually cost him the gig.

As rumors of a Buffalo Springfield reunion tour continued to spring up every couple of years during the eighties, Palmer briefly attempted to put together his own version of a new Buffalo Springfield in 1986. But without the power of that band’s two stars—Young and Stills—the new “Buffalo Springfield Revisited” died a predictable death.

Bruce Palmer and Neil Young first met when the latter joined the Mynah Birds, Palmer’s band with a young Ricky “Rick James” Matthews (ironically it was James who later recommended Greg Reeves for the bass spot in CSN&Y, likely costing Palmer the gig). It was also Palmer who rode shotgun in Young’s hearse when the two of them met up with Stills on that fateful day in a traffic jam on L.A.’s famous Sunset Boulevard—a legendary meeting that led to the formation of Buffalo Springfield.

Bruce Palmer, original bassist for the Buffalo Springfield, was found dead in Belleville, Ontario, Canada, on October 1, 2004, of a heart attack at the age of fifty-eight.

Dewey Martin—Drums (Buffalo Springfield)

Born Walter Milton Dwayne Midkiff, Dewey Martin completed the Buffalo Springfield lineup after being suggested to the band by Chris Hillman of the Byrds. Martin had previously been playing with the Dillards, a country rock band that had recently dismissed Martin after deciding to continue on without a drummer.

Prior to the Dillards, Palmer had played with the Northwest-based rock band Sir Walter Raleigh and the Coupons and had also done some work with fifties rock veterans Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins, and the Everly Brothers. As the oldest member of the band, Martin not only brought much-needed experience to the group, but as Young has since noted, “he was also one hell of a drummer.”

Throughout the trials and tribulations of Buffalo Springfield’s brief existence as a group, Martin stuck to the band like glue. Once they finally disbanded for good, Martin also attempted to carry on with the name, although he was eventually stopped from using it in a legal action filed by Young and Stills (Martin’s “New Buffalo Springfield” was subsequently renamed Blue Mountain Eagle). Martin also signed on for Bruce Palmer’s attempts to revive Buffalo Springfield during the eighties. Eventually, Martin retired from the music business and found work as an auto mechanic.

Dewey Martin was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997 along with the other members of Buffalo Springfield—an event that Neil Young himself famously no-showed.

Buffalo Springfield drummer Dewey Martin died on February 1, 2009, in Van Nuys, California, of natural causes. He was sixty-eight years old.

Nicolette Larson—Vocals

During the seventies, Nicolette Larson earned a reputation as a great backup singer on albums by emerging “new country” artists like Emmylou Harris (Luxury Liner). She first became associated with Neil Young after mutual friend Linda Ronstadt recommended her as a backup vocalist for Young’s American Stars and Bars album. Both Ronstadt and Larson would eventually be heard backing Young as “the Saddlebags” on the very same record.

Young, who by this time had also begun a brief romantic relationship with Larson, used her once again for his Comes a Time album, where Larson can be heard harmonizing with him on his cover of Ian and Sylvia’s “Four Strong Winds,” among other tracks.

Larson’s strong showing on Comes a Time soon led to her own recording contract with Warner Brothers, which released her critically and commercially well-received 1978 solo debut album Nicolette.

Anchored by a strong cover version of Young’s “Lotta Love” (also originally recorded for the Comes a Time album), the album earned raves from the likes of Rolling Stone magazine. However, despite showing such initial promise, the success of her debut album would never again be duplicated.

Larson continued to release solo albums over the years as well as sing backup vocals on albums by artists who mostly fell into the laid-back, seventies and eighties L.A. pop category of people like Christopher Cross and the Doobie Brothers.

Not surprisingly, Nicolette Larson eventually married Warner Brothers house producer Ted Templeman, who was the man behind the boards on many of these records. In 1992, Larson also musically reunited with Young to sing backup vocals on his Harvest Moon album.

Nicolette Larson, who is best remembered for her 1979 Neil Young–penned hit single “Lotta Love,” died on December 16, 1997, from what was officially cited as complications from liver failure related to cerebral edema. She was just forty-five years old.

David Briggs—Producer

Long associated with some of Neil Young’s most classic work—from Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and After the Gold Rush to Harvest and Rust Never Sleeps—David Briggs was also the man behind the boards for some of Young’s least commercially viable albums like Re-ac-tor, Trans, and Old Ways.

Perhaps most notably, Briggs was also the producer for Young’s greatest work with Crazy Horse, where he harnessed the raw power of the Horse as perhaps no other producer could have. Briggs’s final record with Young was 1994’s Sleeps with Angels—another great but often overlooked work in the Neil Young canon.

Briggs and Young famously met when the former picked up the latter when he was hitchhiking, and soon developed a relationship that would result in Briggs getting a co-producer’s credit on Young’s self-titled debut solo album. From there, he went on to produce that album’s classic follow-up Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Prior to their fateful meeting, Briggs had been working at Bill Cosby’s Tetragrammaton Records label. He later produced records for a variety of artists including Alice Cooper, Spirit, Nils Lofgren, Grin, Blind Melon, Nick Cave, and others.

But it was Briggs work with Neil Young that became his true, lasting legacy as a producer. One of the more famous quotes attributed to Briggs came when he once answered the question about whether he produced Neil’s albums, to which he replied “only the good ones.” Another famous Briggs quote probably best sums up his approach to making records, and perhaps best explains why Neil has returned to him time and time again:

“When it comes to rock and roll,” Briggs said, “the more you think, the more you stink.”

It was this low-fi approach to recording—Briggs has also been quoted as saying he would just as soon eliminate studio gadgetry altogether and run a direct line from the instruments to the tape machines—that has perhaps most endeared him to Young (as well as a younger generation of musicians who likewise prefer Briggs’s more basic technique).

Like Young himself, Briggs was a firm believer in capturing the immediacy of the moment, which meant he often had little use for returning later to what he considered a perfectly good track, only to muck it up with overdubs. This, of course, suited Neil Young just fine—particularly when it came to capturing the raw live sound of his work with Crazy Horse on albums like Zuma and Ragged Glory.

Another trademark of Briggs’s work with Neil Young has been his occasional preference for sometimes strange recording locales over the more traditional confines of the recording studio. Much of After the Gold Rush was made in the cramped quarters of Young’s home in Topanga Canyon at the time. For Tonight’s the Night, the tequila-fueled sessions took place at the L.A. Studio Instrument Rentals rehearsal space owned by Ken Berry—where they simply knocked out a wall to accommodate the musical madness surrounding that particular landmark recording.

Briggs has also been known to express his opinions rather strongly, reflecting an honesty that also drew Young’s respect (as an artist who has likewise become known for being rather opinionated himself).

Neil Young’s longtime producer David Briggs passed away on November 26, 1995, following a battle with lung cancer. He was fifty-one years old.

By most accounts, Briggs’s short life was one lived to the fullest. His fondness for “fast cars, beautiful women, Vegas trips, and insulting managers and lawyers” was noted by Neil Young biographer Jimmy McDonough in an obituary written for and published by the Los Angeles Times. David Briggs continues to be missed.

Larry “L.A.” Johnson—Filmmaker, Videographer, Producer

Larry “L.A.” Johnson first met Neil Young as a sound engineer on the legendary film document of the 1969 Woodstock festival (for which he also earned an Academy Award nomination for sound editing).

Although Young’s reluctance to be filmed during CSN&Y’s set that day has long since become the stuff of legend, something about Johnson must have hit a chord within Young, because the two of them have enjoyed a long, and by all accounts very satisfying, working relationship ever since.

Young recruited Johnson soon after Woodstock for his Journey Through the Past film. Young once again turned to Johnson to produce his experimental (and largely unseen) Human Highway, as well as the concert film for Rust Never Sleeps. In 1986, Johnson also directed a Neil Young pay-per-view concert with Crazy Horse called Live from a Rusted Out Garage that has been described by the few who have seen it as the best document of Neil and the Horse live ever captured on film.

Johnson is also credited as a producer for Greendale and Living with War albums, as well as the films that accompanied each of them. As head of Young’s film production company Shakey Pictures, Johnson also oversaw Young’s concert films ranging from Year of the Horse to Red Rocks Live.

Larry “L.A.” Johnson, a filmmaker and producer long associated with Neil Young movie projects ranging from Rust Never Sleeps to Greendale to CSN&Y’s Déjà Vu Live, died of a heart attack on January 21, 2010, at the age of sixty-three.

Ben Keith—Pedal Steel, Guitar, Piano, Multi-Instrumentalist (Stray Gators, Santa Monica Flyers, International Harvesters, and Others)

In addition to being Neil Young’s pedal steel guitarist on albums like Harvest and Harvest Moon (which he also co-produced with Young), Ben Keith was the primary musical collaborator on a number of albums spread throughout Young’s legendary career, including Tonight’s the Night, Time Fades Away, American Stars and Bars, Comes a Time, Prairie Wind, and Chrome Dreams II. Keith also played pedal steel with a number of Young’s touring bands including the Santa Monica Flyers, International Harvesters, and most notably the Stray Gators.

Ben Keith was first tapped in 1972 by Young to work with him on what would end up being Young’s biggest-selling album, the worldwide #1 smash Harvest. After a chance meeting in Nashville, where he was taping a broadcast of the Johnny Cash Show, Young was introduced to Keith by bassist Tim Drummond.

Along with Drummond and drummer Kenny Buttrey, Young and Keith then formed the Stray Gators and began a concert tour to promote the Harvest album, which later carried over into shows featuring the newer, less radio-friendly songs eventually documented on the 1973 live album Time Fades Away.

Keith stayed on with Young for the dark masterpiece Tonight’s the Night and remained a constant on his albums from that point forward. Eventually the Stray Gators officially re-formed for the Harvest “sequel,” 1992’s classic Harvest Moon album. At the time of his death, Keith had been staying at Young’s California ranch and working on yet another new Neil Young album (2010’s Le Noise) with producer Daniel Lanois.

In addition to his work with Young, Keith has worked with such artists as Todd Rundgren, Waylon Jennings, Linda Ronstadt, the Band, Ringo Starr, and Jewel (Keith produced her multiplatinum seller Pieces of You).

Early on in his career prior to his fateful meeting with Neil Young, Keith was well known as an ace Nashville session musician, playing on classic country tracks like Patsy Cline’s “I Fall to Pieces.” Just before his death, Keith had played on the Foul Deeds album by Young’s wife Pegi and had completed a short West Coast club tour with the Pegi Young Band, supporting Bert Jansch.

Ben Keith, the multi-instrumentalist and producer best known for his work with Neil Young for nearly four decades, died as this book was being written on July 26, 2010, at the age of seventy-three.

As early reports of Keith’s passing initially began surfacing on the Internet, there were few details about the nature or even the exact time of his death. However, director Jonathan Demme, who filmed both Young and Keith in the concert documentaries Heart of Gold and Neil Young’s Trunk Show, confirmed that Keith died of a heart attack in a later report published by the Los Angeles Times.

Speaking about Keith in the same article, Demme called him “an elegant, beautiful dude, and obviously a genius. He could play every instrument. He was literally the bandleader on any of that stuff … Neil has all the confidence in the world, but with Ben onboard, there were no limits. Neil has a fair measure of the greatness of his music, but he knew he was even better when Ben was there.”

Neil Young himself acknowledged Keith’s passing onstage at a concert in Winnipeg during his Twisted Road tour. Dedicating the song “Old Man” to his friend and longtime collaborator, Young said “This is for Ben Keith. His spirit will live on. The Earth has taken him.”

Kenny Buttrey—Drums

Aaron Kenneth “Kenny” Buttrey is best remembered as the drummer of note during Neil Young’s transition from the smooth folk-pop of Harvest to the rougher-around-the-edges sound of his Ditch Trilogy records Time Fades Away and Tonight’s the Night. Buttrey played on all three of these pivotal albums in the artistic development of Neil Young, as well as on the concert tours behind them.

Buttrey’s name also comes up frequently as the guy whose grousing about money might have been a contributing factor (though not the only one) in Young’s already foul mood during the tour for Harvest—a series of shows that eventually gave way to the abrupt, audience-confusing turn that characterized the latter part of the tour, as well as his next few records.

Even so, there was obviously something about Buttrey’s skin work that Young liked, as the drummer was brought back for the “sequel” record Harvest Moon twenty years later, a re-creation that was, not coincidentally, also set in Buttrey’s native Nashville.

Predictably, and somewhat humorously in retrospect, Buttrey bitched about the money for those sessions as well.

Born in Nashville in 1995, Buttrey also played on notable recordings by Bob Dylan (Nashville Skyline, Blonde on Blonde, John Wesley Harding) and Jimmy Buffet (his drums are heard on Buffet’s signature tune “Margaritaville”), among numerous others.

Kenny Buttrey died of cancer in Nashville on September 12, 2004. His passing is noted on the inner sleeve liner notes of Young’s 2005 Prairie Wind album (another Harvest rewind recorded in Nashville), alongside that of Young father Scott, who died during the same period.