10

There Was a Band Playing in My Head, and I Felt Like Getting High

After the Gold Rush

Of all the songs in Neil Young’s vast catalog, perhaps none have been as thoroughly and deeply analyzed as the title track of his third solo album, 1970’s After the Gold Rush.

And why not?

On the surface, the song lyrics reference everything from knights in armor, peasants singing, and spaceships flying to lying in a burned-out basement, and, of course, Mother Nature herself on the run in the nineteen seventies (which has subsequently been updated in concert every decade since).

Among the more notable attempts to decipher this most famous of Young’s many great songs is a lengthy article posted by a guy named Randy Schecter on the Neil Young fan site Thrasher’s Wheat.

In his very well thought out post, Schecter makes the case (and quite convincingly I might add) for this song being nothing less than a doomsday prophecy of some distant apocalyptic future event involving UFOs, ecological catastrophe, and nuclear war.

It’s heavy stuff, to be sure.

The thing is, Schecter makes a very good argument for this scenario of a biblical Armageddon, and the song lyrics—which are among the most vividly descriptive that Young has ever written—seem to back this up.

This would all be fine and dandy, of course. At least if that was what this particular song was actually written about.

The thing is, it most likely isn’t about the aliens in spaceships rescuing us from a future doomsday or the visions swirling about Randy Schecter’s keyboard at all. Rather, the lyrics of “After the Gold Rush” are most likely about the more personal apocalypse occurring in Young’s own life at the time.

Like most everything else that exists in the Neil Young songwriting canon—from his most autobiographical songs like “Helpless,” to songs that more or less eulogize things like how “I watched the needle take another man”—“After the Gold Rush” could be about any number of things. But it’s just as likely that what Neil was really singing about came from a place having more to do with personal concerns than anything as apocalyptic as doomsday or as otherworldly as being beamed aboard flying saucers from outer space.

Reprise Records promo 45 for “After the Gold Rush.”

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

Specifically, a decent case could be made that “After the Gold Rush” was among the earliest of Neil Young’s many antidrug songs.

Consider the lyrics coupling how “I felt like getting high” to how Neil was “thinking about what a friend had said” and “hoping it was a lie,” and the actual sentiments of this song become crystal clear.

At the time After the Gold Rush was being recorded, Young found himself faced with the difficult decision of having to fire Crazy Horse—his band of choice at the time—even after he had already completed several sessions for his impending new album, with what most will agree (warts and all) was his greatest band.

The lines in this song about “a band playing in my head, and I felt like getting High” are particularly telling when the condition of guitarist Danny Whitten is taken into account.

Whitten, who by this time was deep in the throes of a severe addiction to heroin, had in fact become a no longer ignorable liability to Neil Young and Crazy Horse—the band that he cared the most deeply about on an artistic level (even as CSN&Y was still paying the bills at that point).

A short tour in 1970 produced some undoubtedly great shows (most notably the Fillmore East concerts eventually documented on the Archives boxed set).

But more often, Whitten had become so consumed by his increasing dependency on heroin and other drugs that he had even taken to passing out onstage in the middle of concerts (if you listen closely to the Live at Fillmore East album. you can even hear Neil Young admonishing him for this).

It is perhaps here that the line in “After the Gold Rush” that follows the part about the band playing in his head and feeling like getting high begins to make the most sense. “Thinking about what a friend had said, I was hoping it was a lie” is another of this song’s key lines, and one that rings tragically true when read in this more personal context.

For Young, watching his friend—a great musician in his own right—waste away before his eyes had to be a most painful experience. But as is so often the case with addiction, this same pain often turns quickly to a deeper hurt and resentment.

“I sing the song because I love the man,” he later went on to sing in “The Needle and the Damage Done.” “I watched the needle take another man.” The sadness heard in that song is equally mixed with a deep sense of hurt and betrayal. In many ways, “After the Gold Rush” was a precursor to the more direct lyrics about drug-related loss later heard on songs like “The Needle and the Damage Done” and on albums like Tonight’s the Night.

In addition to the inner turmoil taking place within Crazy Horse, Young was also undergoing considerable upheaval in his personal life at the time the After the Gold Rush album was being recorded. His divorce from first wife Susan Acevedo, and his move away from Topanga Canyon, also took place the very same year.

Flying Mother Nature’s Silver Seed to a New Home in the Sun

Still, there were some apocalyptic elements in the songs for Young’s third solo album—at least initially. And his friends in the community of artistic types residing in Topanga Canyon were undeniably a big part of that—even as he himself was already eyeing his “new home in the sun.”

At the time, actor/director Dennis Hopper—fresh from the unexpected success of 1969’s Easy Rider—had been given the green light from Warner Brothers Pictures to develop his own film projects. As a result, Hopper and Neil Young’s mutual friend Dean Stockwell developed a loose script for a projected film called—you guessed it!—“After the Gold Rush.”

In the end, the album that eventually became Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush really had little to do with Stockwell’s original script for a projected film about an ecological disaster (something about a tidal wave hitting Southern California). But in retrospect one can certainly see where those original seeds may have been sown (particularly in the title track—where perhaps Randy Schecter’s detailed analysis posted on Thrasher’s Wheat finally begins to make a little more sense after all).

One of the many vinyl pressings of “Southern Man” from Neil Young’s third solo album After the Gold Rush. The song’s controversial lyrics sparked a response from Lynyrd Skynyrd in the form of their own single “Sweet Home Alabama.”

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

As it ended up, After the Gold Rush became a far more personal statement from Young, and one that produced some of his most pointed songwriting to date. From this moment forward, Young’s emergence—not just as one hell of a loud guitar player capable of making a big racket with Crazy Horse, but also as a highly sophisticated songwriter comparable to the true greats like Bob Dylan—would never be ignored again.

Of course, being the artistic iconoclast that he is, subsequent changes in Neil Young’s artistic direction would only serve to further muddy these already murky waters, as future audiences would discover soon enough. The Ditch Trilogy and the wild genre hopping of the “lost eighties” were still some distance down the road. But by following the guitar-heavy Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere with the deliberately mellower singer-songwriter vibe of After the Gold Rush, Neil Young demonstrated that abruptly shifting musical gears—regardless of any commercial, critical, or even personal circumstance—came as naturally to him as breathing is to the rest of us.

By firing Crazy Horse (even though it turned out to be temporary), he showed he could be ruthless as well. Even though two of the songs from the original 1969 sessions with Danny Whitten and Crazy Horse survived to make the final record (“I Believe in You” and “Oh Lonesome Me”), and Whitten returned to add overdubs as the album neared completion, Young certainly proved he had no problem handing out pink slips if his own increasingly exacting standards weren’t being met to the letter.

Sailing Heart Ships Through Broken Harbors

The majority of After the Gold Rush was recorded in a makeshift studio in the basement of Young’s relatively modest home, establishing a pattern for making records in strange locales that would follow him throughout his career.

In some ways, the album has a flat sort of sound to it—particularly when compared to the dense and much thicker-sounding bursts of heavy guitar created by Neil Young and Crazy Horse on Gold Rush’s predecessor, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. If the idea here was to create a “low-fi”-sounding album, in places the actual result is more like “no-fi,” perhaps owing at least in part to the relatively cramped quarters where much of the music was made.

The space problem was solved soon enough, however, when Young purchased the several hundred acres of land near San Francisco that he renamed the “Broken Arrow Ranch” that same year. Broken Arrow remains home to Young and his family to this day. It has also been home to a number of other central figures in his life over the years, ranging from one-time girlfriend, actress Carrie Snodgress (and by some accounts, most of her family and friends as well) to chief musical co-conspirator Ben Keith, who lived at Broken Arrow up until his death in 2010.

The move would also signal the end of Young’s first marriage to Susan Acevedo, which by that time had become a casualty of his increasing stardom and the constant parade of willing girls surrounding him that came along with it. As far as the possibility of Young actually being unfaithful, if it ever happened, the rock press and the tabloids never reported it. More likely, Susan probably just got sick of all the young girls throwing themselves at her husband. By all accounts, the divorce was an amicable one with Young settling for something in the neighborhood of $80,000.

Reprise Records “double-A side” single release of “After the Gold Rush” and “Only Love Can Break Your Heart.”

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

For the sessions that made up the bulk of After the Gold Rush, he retained Ralph Molina from Crazy Horse as drummer and brought in CSN&Y bassist Greg Reeves as well as a young hotshot guitarist named Nils Lofgren.

As the story goes, Lofgren met Neil Young after sneaking backstage at a Washington, D.C., concert. After introducing himself, Young asked the kid if he had any songs, and after hearing several of them invited him out to Los Angeles. After walking the distance from the L.A. airport to Young’s home in Topanga Canyon carrying his guitar on his back, Young signed him up to play on the album. But as was so often the case with Young, there was a catch.

He wanted Lofgren—the guitarist—to play the piano. The fact that Lofgren wasn’t a piano player made no difference. Whether this was simply one of Young’s more impulsive artistic whims, or just another example of the way he asserts total and complete control over every note played on his records (something that later drove the Stray Gators fairly crazy during the making of Harvest), Lofgren did as he was told and passed his audition by fire with flying colors.

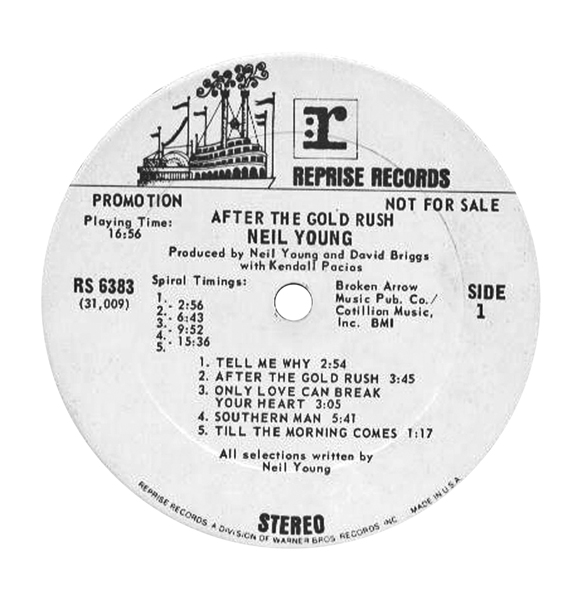

Reprise Records promo pressing of Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush LP.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

Young later explained away the decision simply by saying “I hate musicians who play licks.” It was an explanation that would be repeated several more times over the years to justify the notorious control he exercises over the hired help. If there are any two clichés that sum up his approach to making records, they would probably come down to “more soul, less licks.”

With his debut as a pianist (and yes, as a guitarist too) on After the Gold Rush, Lofgren began an on-and-off association with Neil Young that would last more than a decade. In addition to helping get Lofgren’s own group Grin off the ground (with a David Briggs–produced debut album), Lofgren has also put in time with the lunatics in Crazy Horse and as a member of the infamous Trans Band in the early eighties.

These days, when Lofgren isn’t recording solo albums and teaching guitar online, he serves as one of the three guitarists with Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, which he joined as a full-time member in 1984.

I Heard Screamin’ and Bullwhips Crackin’

Released in June 1970, After the Gold Rush became Neil Young’s biggest hit up to that time, reaching the top ten of Billboard’s albums chart, where it peaked at #8. The mellower sound of the album also effectively set the table for the worldwide #1 smash that would occur with its follow-up Harvest.

Although the album signaled an artistic shift to more of a singer-songwriter focus, the album also has its fair share of rockers, none of which would create a bigger fuss than “Southern Man.”

In the five-and-a-half-minute version that appears on the album, “Southern Man” lacks some of the punch heard in the live versions on the CSN&Y tour that took place in the summer of that same year. In those shows, the song could often stretch out to nearly twenty minutes courtesy of the fiery guitar exchanges between Young and Stephen Stills.

A very good, but not quite great, example of this can be heard on CSN&Y’s 1971 live album 4-Way Street. By contrast, on the studio version, Young’s guitar solos are still crisp and razor sharp, but they also seem to be over before they ever really get started. Perhaps owing to the much flatter sound of the album, they also lack much of the bite heard on concert stages that summer. A definitive version of “Southern Man” remains a major hole in Young’s catalog.

The lyrics, however, stirred up the predictable controversy with southern fans, and particularly with the southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd. With its images of crosses burning, bullwhips cracking, and of course, those black men who are seen “comin’ round,” “Southern Man” may be one of the more naïve attempts at a political statement ever made by Young. For all of its good intentions, “Southern Man” is an even more confusing political statement when you consider it came the very same year as the much more direct, cutting-straight-to-the-bone lyrics heard in what is arguably his greatest “protest song” ever—CSN&Y’s “Ohio.”

Single picture sleeve 45 release of “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” from After the Gold Rush.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

Either way, the blunt, and perhaps somewhat misguided, lyrical bombs Young was hurling down on Dixie with “Southern Man” were certainly not lost on Lynyrd Skynyrd vocalist and lyricist Ronnie Van Zant (who was a big Neil Young fan himself, by the way).

Predictably, the good old boys in Lynyrd Skynyrd (if it wasn’t them, it could just as easily have been the Allman Brothers) were quick to respond with exactly the southern pride you’d expect, releasing the single “Sweet Home Alabama.” To this day, the song’s most famous line remains, “Well I hope Neil Young will remember, southern man don’t need him around anyhow.”

Interestingly, Van Zant later wore a Neil Young Tonight’s the Night T-shirt on the cover of Skynyrd’s posthumously released Street Survivors album (three members of the group, including Van Zant, lost their lives in a plane crash just weeks prior to that album’s release). An even more curious story handed down over the years says Van Zant was buried wearing the very same Neil Young T-shirt.

Find Someone Who’s Turning and You Will Come Around

In addition to “Southern Man” and the title track, After the Gold Rush’s other highlights include “When You Dance, I Can Really Love.” In this rocker that finds Neil Young holding back on the guitar histrionics (well, relatively speaking anyway), Jack Nitzsche effectively steals the show from the star with a ripping performance on the piano (speaking of guys playing licks).

“Don’t Let It Bring You Down” is an irresistibly mellow tune that is something of a precursor to the melancholic feel that would more fully manifest itself on Harvest. The song is also a textbook example of the lonesome-sounding, world-weary voice that is arguably the single most identifiable element of what most recognize as Neil Young’s “sound” (if there even is such a thing).

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” is likewise another, if slightly more lightweight exercise in the sort of singer-songwriter introspection so closely identified with its early seventies period, and for better or worse, with Neil Young himself. It also became a big radio hit, further setting the stage for the huge commercial breakthrough still to come with Harvest. Of the leftover 1969 sessions with Crazy Horse, “Oh, Lonesome Me” is also a standout—and here once again it’s largely due to the achingly lonesome quality of Neil Young’s voice.

In the final analysis, After the Gold Rush would have to be considered a major triumph if only for the very considerable merits of the title track alone—it’s easily one of Young’s greatest songs. From a commercial perspective, it’s also fair to say that it was a milestone in his career up to that point. As an overall artistic breakthrough, however, the arguments become a lot less convincing, particularly when the album is compared to such masterpieces as Tonight’s the Night, On the Beach, Rust Never Sleeps, or even to latter-day albums like Freedom, Harvest Moon, and Sleeps with Angels.

That said, Neil Young’s follow-up to After the Gold Rush blew the doors wide open, and nothing would ever again be the same.