17

More to the Picture Than Meets the Eye

Human Highway, Rust Never Sleeps, and the Punk-Rock Connection

The end of the seventies marked one of the stranger, more polarized periods in the history of rock ’n’ roll.

FM Rock radio stations, once the place for the most progressive, artistically challenging, and experimental music—the kind of stuff that the more traditional, top forty formats wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot microphone—had become about as sterile and sanitized by strictly controlled playlists and formats (which were often determined by consultants and demographic research) as their much more conservative counterparts on the AM dial.

The end result of this was a steady and ultimately mind-numbing stream of highly formulaic, softer-leaning rock created by bands with a slick, recording studio-produced sheen like the Doobie Brothers, Fleetwood Mac, the Eagles, and Steely Dan.

Occasionally, the FM rock stations would break these up with older hard-rock cuts by bands like Led Zeppelin and the Who. But even in those cases, they stuck mostly to the familiar, overplayed hits like “Stairway to Heaven” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Meanwhile, even in the hard-rock arena, the only hope for new artists getting their records played was by likewise watering down their sound to fit the increasingly tight playlists of FM rock radio formats. This subsequently gave rise to a newer wave of formula rock bands like Boston, Styx, Foreigner, and Journey.

Of these bands, Boston made the biggest splash, with their self-titled debut album selling a mind-boggling seven million copies.

But it was Journey that had the longest legs.

Consisting of ex-Santana and Frank Zappa alumni such as one-time teenaged guitar prodigy Neal Schon and monster drummer Aynsley Dunbar, and fronted by a high-pitched vocalist named Steve Perry—Journey’s credentials as a group of amazing musicians were never in question. But the fact that they cashed it all in for a ride to the top that lasted well into the eighties (and continued long after the other formula rockers of their day had bitten the dust, careerwise) ended up costing them both their artistic credibility and any hopes for critical respect.

Meanwhile, the record business itself was in the best shape it had ever been.

Multiplatinum blockbusters like Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, the Eagles’ Hotel California, and the aforementioned debut from Boston had all but assured that. The concert business was also booming. Tours by the old warhorses like the Stones, Zeppelin, and the Who were selling out stadiums, even as the increasingly theatrical stage shows of groups like Kiss, Queen, and Aerosmith were bringing bigger, bolder, and better lighting, staging, and production values to the shows themselves.

The question nearly everyone in the music business was collectively asking themselves privately by the end of the seventies, though, was a simple one:

If everything was going so damn great, why were so many of the music critics wondering aloud where rock’s originally cutting edge had gone? And exactly when and how did the audience for this music become so damned polarized?

“The kids,” as so many jaded music promoters referred to their bread and butter back then, were clearly looking elsewhere for their music. That much was painfully clear.

As much as bands like Journey, Boston, and the Eagles continued to sell truckloads of albums, and Kiss and Led Zeppelin continued to sell out arenas and stadiums, rock fans were becoming split into a set of opposing camps, with the battle lines being drawn based on little more than genre preference. Rock ’n’ roll had become divided against itself like no other time since the post-Elvis, pre-Beatles era of pop crooners and white-bread teen idols like Fabian and Pat Boone.

As everyone seemed to be collectively searching for the next big thing all at once, some of these fans found their refuge in disco—which had become kind of a catchphrase describing a music genre encompassing everything from the tight, gritty funk sounds of Earth Wind and Fire to the slickly produced, albeit considerably sped up, R&B-based rhythms of Nile Rodgers and Chic and the white bread Euro-pop of Abba.

Once the Bee Gees took their somewhat sanitized version of studio-enhanced pop-disco hits into the stratosphere with their blockbuster, multimillion-selling soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever, the street sounds of disco moved out of the black and gay clubs and into the American mainstream.

This in turn prompted an immediate backlash of “Disco Sucks” fashion gear and record burnings, often sponsored or promoted by FM rock stations. The racist and homophobic undertones of these “demonstrations” were so thin as to be virtually transparent.

A few other disgruntled rock fans—okay, make that more than a few—turned to the progressive rock of synthesizer-driven bands like Genesis, Yes, and Pink Floyd—groups that specialized in a fusion of rock, jazz, and classical sounds, as well as extended solos that could take up entire sides of an album. The prog-rockers often made for a curious fan base, divided as it was between the stoners who enjoyed the way the spacier elements of prog could enhance a good bong hit, and the nerdy types who enjoyed the pseudo-intellectualism of rock music that incorporated literary influences from J. R. R. Tolkien to Greek mythology in the lyrics.

But the one force that was driving the divisions among musical genre lines more than any other—including disco—was punk rock.

This Is the Story of Johnny Rotten

Punk rock in the seventies was the sort of phenomenon that could only happen in a musical climate that was starved for artistic change the way that rock ’n’ roll was as the decade lumbered to a close.

Punk was the rallying cry—more like an explosion, really—of an entire generation of rock fans who had watched their heroes grow into bloated shadows of their former artistic selves, and who had stood by as the resulting excesses of money and success had seen the distance between audience and performer grow into something more like a continental divide.

The promise of a cultural, political, and societal revolution once represented by the sixties rock generation had largely become silenced. Not only was the music’s original cutting edge long gone, it seemed that yesterday’s culture-bending radicals had in fact turned into today’s musical conservatives.

In its seventies infancy, punk sought to bring rock’s initial immediacy back to the streets on a gutteral, visceral level. By bringing together elements of music, politics, and a weird sense of anti-fashion, along with plenty of prerequisite attitude, punk was by its very nature the kind of collective “fuck you” directed toward the established order of things not seen in rock ’n’ roll since the mid- to late sixties.

Only this time, the enemy was no longer the over-thirty generation. In this case, the enemy was the rock music establishment itself.

Although punk had considerable roots in the Detroit garage rock of bands like Iggy and the Stooges and the more politically charged MC5, the seventies punk rock scenes were centered primarily in New York and London. In New York, a particularly energized scene emerged in clubs like CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City, and was centered around bands like the Ramones, the New York Dolls, Television, and the Talking Heads, as well as artists like Patti Smith and Richard Hell.

Where Patti Smith, Television, and the Talking Heads represented more the leftover school of avant-garde experimentalists like Lou Reed, it was the fast, young, loud, and snotty minimalist rock of bands like the Dolls and the Ramones that first caught fire across the pond in England.

Applying the same fuck-you attitude of the Ramones to a harsher, more direct message fueled by a crippled economy and the conservative political climate in the U.K., bands like the Clash and the Sex Pistols soon brought their own elements of revolution into the mix. Although the Clash were undoubtedly the most overtly political of these bands, it was the Sex Pistols, fronted by the snarling but undeniably charismatic Johnny Rotten (Lydon) who took it the most over the top with singles like “Anarchy in the U.K.” and “God Save the Queen” (because, after all, “she ain’t no human being”).

Although none of these bands sold squat in America—at least not initially—the buzz and the curiosity factor surrounding punk was still significant enough to create a cult following of fans that could guarantee a group like the Ramones, for instance, a decent house at a 700–1,000 seat club in just about any major city in America.

Put them on a punk rock triple bill with, say, the Talking Heads and Blondie, and you might even sell out a three thousand-seat theatre or auditorium. Imagine that.

Meanwhile, there was still enough lingering curiosity about the punks within the mainstream arena that even a more traditionally based classic rock-’n’-roll band like Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers could draw attention simply by adopting a little punk attitude (or in the case of Petty, by putting him in a black leather jacket on the cover of the Heartbreakers’ debut album).

Another way of breaking a band like Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers was to book it on one of those punk-rock triple bills. The very first time I saw the group was at just such a punk show, where they opened for the Ramones in Seattle.

The record companies also took notice, and did little to discourage any punk connections with then breaking new artists like Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe, and Graham Parker—who, although they shared some of the same rawer, back-to-basics minimalist aesthetics of the punks, could hardly be lumped into the same category.

This subgenre of punk eventually morphed into “new wave” and a whole slew of new bands wearing skinny ties.

But that’s another story …

It’s Better to Burn Out Than It Is to Rust

Lying somewhere in the middle of all of this musical polarization was one Neil Percival Young.

Although he had certainly carved out his own well-earned reputation as an uncompromising artistic maverick and all-around iconoclast during the earlier half of the seventies with albums like Tonight’s the Night and On the Beach, the commercial success of his latest album Comes a Time had put Young squarely back in the middle of the road.

In offering up the song “Lotta Love” to his then girlfriend Nicolette Larson (who went on to have a typically disco-driven late seventies hit with a very slick-sounding studio production and eventually married its producer, Ted Templeman), Young had even joked that he was giving her his “Fleetwood Mac” song.

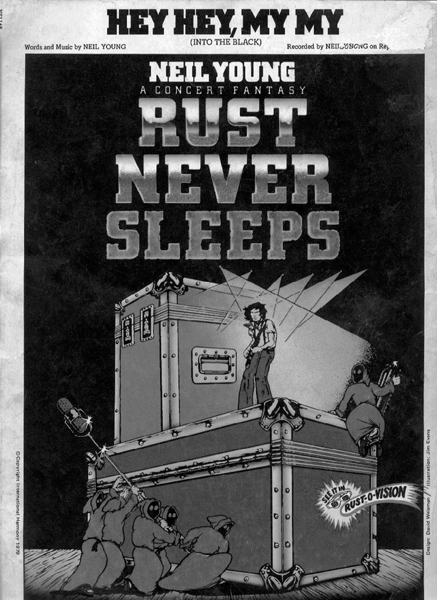

Sheet music for “Hey, Hey, My, My (Into the Black)” from Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s landmark album Rust Never Sleeps.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

For his own part, Young was also settling down from some of the wilder, druggier, skirt-chasing ways of his early career.

Following his split with Larson, he married Pegi Morton, who he had gotten to know as a waitress in a diner near his ranch in 1977. Their son Ben (who, it was later discovered, suffered from an even more severe form of the cerebral palsy that afflicted his older brother Zeke), was born the next year.

What was clear, though, was that Young had taken notice of the bigger picture of the musical marketplace, including what was happening with the punks.

Although the emergence of MTV—along with the rise of albums like Michael Jackson’s Thriller and Prince’s 1999, the cultural ascendance of hip hop, and the brief, early eighties success of punk rock bands like the Clash—would soon bring a thankful end to the musical and racial divisions that still existed in the late seventies, the reality of a musically charged, polarized climate in rock ’n’ roll was still very real at the time.

What made Neil Young stand out—and indeed, largely alone—from many of his fellow rock “dinosaurs” (as the punks liked to call them) was his tacit endorsement of the same punks who had infuriated so many of his peers from the sixties and seventies rock era.

Rather than speaking out against the rising tide of the new punk rock guard in the same condescending and dismissive tones as so many of his fellow Woodstock-era rockers—including his own bandmates in CSN&Y—did back then, Neil Young chose instead to embrace them. As much as it may have seemed a strange decision at the time, it was one that would pay considerable commercial and artistic dividends down the road.

As later comments in the eighties defending his syntho-pop album Trans have long since demonstrated—comments where he cited bands like the Human League and A Flock of Seagulls in making his arguments—it is entirely possible that Young was nowhere near as plugged into the new music scene as he may have liked the rest of the music world to believe.

However, and to this day, he still mostly stood alone among his dinosaur rock peers at the time in his ringing endorsement of punk rock, fostering a rare connection with (and influence on) newer, younger rockers that has continued well into the nineties and beyond with bands like Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Radiohead, and Pearl Jam (who Neil eventually even made a record with).

It’s no coincidence that Young would eventually be labeled “the Godfather of Grunge” in the nineties.

More importantly, he put his money where his mouth was with his next couple of projects.

Out of the Blue and into the Black

Neil Young’s early endorsement of, and brief association with, the experimental new wave band Devo is one of the more curious choices of his entire career.

If Young was looking to make a commercially motivated and calculated connection with the emerging punk-rock and new wave movements, there was certainly no shortage of bands that might have been better choices for allowing the aging rock veteran to voice his allegiance to the new revolution.

But, of course, as he has so adamantly and repeatedly demonstrated over the years, Young has never been one to opt for the most obvious choice.

His introduction to Devo came by way of his pal Dean Stockwell, who had been passed a tape of the Akron, Ohio-based proto-punkers by his friend Toni Basil (who was then still a few years away from her one-hit wonder status with the early eighties new wave and MTV staple “Oh, Mickey (You’re So Fine).”

Basil’s passing of the tape to Stockwell completed a chain of events that had seen Devo’s demo tape pass through the hands of David Bowie and Iggy Pop, among others.

If nothing else, Devo was a band of true weirdos, even going by the oddball standards of seventies punk. But they were also a strikingly original band of weirdos.

Fronted by art-school types Mark Mothersbaugh and Jerry Casale, Devo’s specialty was a brand of minimalist, robotic, pre-new wave rock with an accent on herky-jerky rhythms and lyrics spouting their strangely existential punk philosophy of “devolution.”

The band would routinely dress in the sort of matching hats and yellow jumpsuits that could be readily purchased at the nearest K-Mart, and that often gave them more the appearance of a haz-mat team than a traditional rock-’n’-roll band. Donning these makeshift outfits, they would also perform original songs like “Mongoloid” and “Are We Not Men? (We Are Devo)” alongside such covers as their deconstructed take on the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”—all the while jerking about the stage in a kind of robotic unison.

What wasn’t there to like, right?

Mothersbaugh also adopted numerous bizarre stage personas—the most notorious of which was “Booji Boy,” a full-grown baby, complete with the oversized, presumably poopy diapers to match.

I Got Lost on the Human Highway

If Devo were something of an acquired taste, they were one that Neil Young “got” instantly.

For their part of the bargain, Devo got both a professional management contract with Elliot Roberts’s Lookout Management, and a record deal with Warner Brothers. Young, on the other hand, was given the opportunity to mostly be made fun of by Devo’s audiences (such as when crowd members shouted “Real Dung” at him after he showed up for one of their more infamous surprise shows together at San Francisco’s Mabuhay Gardens).

Devo did nothing to discourage this kind of abuse, of course, and for his own part, Young good-naturedly accepted it for the joke it largely was. In the long run, though, his association with Devo produced something of far greater value.

If the pairing of Devo and Neil Young seemed an unlikely one, the common ground they found can probably best be summed up as a meeting of two genuinely oddball sets of minds. So, when Young recruited the self-proclaimed “devolutionists” to play nuclear waste workers for his truly weird film project Human Highway, the pairing was as natural as the sum of these two equally combustible elements could be. Promotional materials for the film proudly declared that “It’s so bad, it’s going to be huge.”

In retrospect, Human Highway—a self-described “nuclear comedy” that also features a cast including Stockwell, Dennis Hopper (at the height of his substance abusing craziness), Sally Kirkland, and Russ Tamblyn—is one of those bizarre experimental messes that only someone with money to burn like Neil Young could have gotten away with.

With such a colorful cast of characters, it is, of course, needless to say that considerable wackiness ensued during the making of the film.

In one particularly notable incident, Kirkland was apparently stabbed by a knife-wielding Hopper, which prompted a lawsuit by the actress against, among others, Hopper and Neil Young. For his part, Hopper claimed it was an accident that occurred while he was “in character” for his role as “Cracker,” a cook at the same diner where Kirkland played a down-and-out waitress. Her eventual lawsuit (which she lost) was finally heard in 1985, at right around the same time Young was fighting another battle for his artistic life against David Geffen. Neil Young spent a lot of time in court that year.

There is good reason that Human Highway went from a limited theatrical release to cut-out oblivion in near record time. Nowadays, provided you can even find an original copy, of course, it’s a much-coveted collector’s item.

The film, which is said to have evolved from an earlier, even weirder and more off-the-wall film project called “The Tree That Went to Outer Space,” loosely revolves around some sort of future apocalyptic nuclear event. The loose story is intertwined with footage of Young and his friends in private moments, playing music and generally getting wasted out of their minds. The film had no script to speak of and was subsequently seen by virtually no one.

In the scenes with any actual dialog, Young played two characters: a mechanic named Lionel Switch (an obvious reference to the electric toy trains he had loved since his childhood, and the company he eventually ended up buying into), and a drug-addled rock star named Frankie Fontaine (who, it is claimed by some, was inspired by David Crosby).

But in what is probably the most memorable scene in Human Highway, Young and Devo bash out a ridiculously long (and loud) version of “Hey, Hey, My, My (Into the Black),” a song Neil had co-written with his old bandmate in the Ducks, Jeff Blackburn. In providing vocals to the song, Mothersbaugh, adopting his ridiculously over-the-top Boogi Boy persona, sings—or, more like incoherently shouts—the lyrics to the song from an oversized crib, injecting a line of his own that would greatly inspire Young’s very next project.

The line was “Rust Never Sleeps.”

What Young did with this single line—inspired by Devo’s art school days working on an ad campaign for something called rustoleum, and then adopted by the band as a tongue-in-cheek part of their “devolutionist” philosophy on the corrosive nature of humanity—was to run with it in a way that would play a pivotal role in producing one of his greatest albums.

When Young brought the song back to Crazy Horse—the band he would later tour and record it with—he made a particular point of playing back the loud, unhinged version of it that he had committed to tape with Devo, and asking them to recreate it.

Members of Crazy Horse have long since been quoted as saying that they learned to play, and perhaps even overplay, their asses off on the song.

It’s Better to Burn Out

Rust Never Sleeps, the album borne out of this period and released by Warner Brothers in June 1979, is, hands down, one of Neil Young’s greatest records.

But even more than that, it is the album that forever bridged the seemingly unfathomable generation gap that had existed up to that time between the punks of the late seventies and early eighties, and the classic rock of the hippies that preceded them. In Neil Young, the punks had found an unlikely link between past, present, and future. He would remain an unwavering supporter of, and influence on, younger bands for years to come as a direct result.

Comprised of live recordings that Young made both solo and with Crazy Horse during 1978, and later augmented with studio overdubs (mainly with the vocals), the centerpiece of Rust is also what became its unofficial title track.

The two versions of the song “Hey, Hey, My, My”, that bookend the album include an acoustic opening take with just Young on guitar and harmonica, and a full-on electric assault with Crazy Horse at the end. The latter version rocks with a ferociousness that is nothing short of louder than God.

As much as this song is the centerpiece of what is undeniably one of Young’s greatest albums, and as much as it has taken a well-deserved position as an all-time rock-’n’-roll classic, there is not so much as a single clunker in the seven songs on the album that separate both “My, My, Hey, Hey (Out of the Blue)” and “Hey, Hey, My, My (Into the Black).”

But it is this song that really sets the tone for the entire record (as well as the entire Rust Never Sleeps concept and tour that produced it).

Right from the get-go, and with the tragic death of Elvis Presley still fresh in many people’s minds in 1979, Young spins a tale that takes Devo’s devolutionist philosophy of “Rust Never Sleeps” one step further to equate the King’s sad end with the struggle for aging musicians like himself to maintain a sometimes tenuous grip on their own artistic relevance in the wake of their own creeping mortality. In other words, “It’s better to burn out than to fade away.”

“The King is gone, but he’s not forgotten,” Young sings in one of this song’s most memorable lines. “This is the story of Johnny Rotten.”

In equating these two unlikely antiheroes—the bloated “king of rock ’n’ roll” who had so recently died facedown near the crapper, and the snarling punk-rock brat who relished nothing more than spitting in the face of everything so-called dinosaur rock represented in 1978—Neil had perfectly connected the dots between them. In one of the more brutally honest statements on the nature of rock-’n’-roll mortality ever written, he also turned the mirror directly back upon himself as an aging artist striving to remain relevant during these rapidly shifting times, even while questioning the point of doing so at all.

Japanese pressing of Rust Never Sleeps.

Courtesy of Tom Therme collection

He may not have known it back then, but it was one of Young’s boldest artistic statements to date, and one that time has since proven to be one of his most enduring ever. Coming from an artist as historically guarded as Neil Young, the song was also a milestone on a number of levels. First and foremost, it represented an uncompromisingly honest peek into the looking glass of an artist already eyeing his own place in history.

“It’s better to burn out than to fade away,” he sings. In light of the subsequent deaths (inflicted by gun or otherwise) of artists ranging from John Lennon to Kurt Cobain, these words have an almost prophetic ring to them.

At the time, however, Young’s referencing of Johnny Rotten, the snotty lead singer of the punk-rock upstart Sex Pistols, at all—and in the same line as the late, great king of rock ’n’ roll, no less—was considered truly shocking.

Sandwiched in between the alternating versions of “My, My, Hey, Hey” on the album are some of Neil Young’s greatest songs.

The fact that Rust Never Sleeps is largely a live album consisting of new material is of little consequence. Other artists of the period—most notably Jackson Browne with Running on Empty—had also done this. But no one had done it quite like Neil Young did with Rust.

In the years since its original release, the album has also gone down, along with Harvest, as one of his most consistent catalog sellers. There are numerous other great songs on Rust that could be rightfully singled out for praise as among his best.

“Pocahontas” comes most immediately to mind here. One of the best of his many great Indian-themed songs, this one revolves around an imagined meeting between Young, Marlon Brando (the legendary actor was at the time particularly well known for his support of Native American issues), and Pocahontas herself, sitting around a campfire. In the song, Young fantasizes about sleeping with Pocahontas, “to find out how she felt.”

In earlier versions (the song was first recorded as part of the mythically aborted Chrome Dreams album), Young and Brando are joined at the campfire by then infamous Nixon crony and Watergate conspirator John Ehrlichman.

“Thrasher” is another standout, if for nothing else, its blasting of Young’s former bandmates in CSN&Y. Outside of the Beatles, Young’s on-again, off-again, love-hate relationship with Crosby, Stills, and Nash is one of the most storied in all of rock ’n’ roll, and at the time of Rust Never Sleeps, you have to assume that things were not particularly rosy amongst the parties involved.

In lines like “So I got bored and left them there, they were just dead weight to me, better down the road without that load,” Young seems quite content to leave his pals in CSN&Y behind for good. The song continues, “But me I’m not stopping there, Got my own row left to hoe, Just another line in the field of time,” just before offering what seems to be a final twist of the knife with a reference to “dinosaurs in shrines.” This may or may not be Young’s way of equating his former bandmates with the derogatory term Johnny Rotten and the rest of the punks routinely used to dismiss members of the older rock generation back then.

Young and his CSN&Y bandmates would eventually reconcile (again), of course.

In fact, they would go on to record a pair of largely forgettable reunion albums, and then go out on a pair of much more noteworthy tours (particularly in the case of the post-9/11 Freedom of Speech tour behind Young’s anti-Bush album Living with War).

We’ll have much more on that later on in the book.

But speaking of tours …

Rock ’n’ Roll Will Never Die

The one-month concert trek that originally spawned the Rust Never Sleeps album, was first conceived as a series of shows with Crazy Horse designed to promote the mellower, more commercially accessible Comes a Time release.

Soon enough, however, it ballooned into something else entirely—spawning not only the Rust Never Sleeps album, but a subsequent double live release and concert film as well.

No one is exactly sure what Young was thinking at the time of what became the Rust Never Sleeps tour (as if anyone ever does). But the wheels turning in his head seemed to include everything from visions of giant-sized amplifiers and hooded, red-eyed, pint-sized roadies (that looked like something straight out of the Ewok characters from Star Wars), to a determination to boldly go where no man’s eardrums had gone before.

Somehow, it not only all worked, but also went on to create one of the more pivotal concert tours in rock-’n’-roll history.

What is clear today is that this one month’s worth of shows—culminating in the October 22, 1978, performance captured for posterity on the Rust Never Sleeps concert film and Live Rust double concert album)—constitute some of the loudest, most abrasive-sounding rock ’n’ roll Neil Young and Crazy Horse have ever played. It has long since gone down as one of those “you had to be there” moments, and the stuff of legend for Young’s most devoted fans. Much of the San Francisco Cow Palace performance can also be heard on the original Rust Never Sleeps album (albeit in overdubbed versions) of the original new songs that were debuted on the tour.

To this day, roadies and others associated with this tour recall personal memories of chaos, mayhem, and hearing loss.

The Live Rust album is today regarded by many fans as Young’s best live release ever, and as one of the best live rock albums of all time (although some fans will tell you that the nineties release Arc-Weld trumps it, at least in terms of sheer overall volume). Interestingly, the only song from Comes a Time, the commercial folk-pop album the tour was originally designed to promote, represented is Young’s self-described “Fleetwood Mac” number, “Lotta Love.”

Even more revealing, though, is the filmed document of the tour, shot primarily at the Cow Palace show in San Francisco.

This footage is largely grainy by today’s high-definition, Blu-ray standards, but reveals an artist at the top of his game. From the oversized mikes and amplifiers and the hooded, Star Wars–inspired “road-eyes” (as well as characters like Briggs playing Dr. Decibel) onstage, all the way through to the taped Woodstock stage announcements bridging the gaps between sets, and the “Rust-O-Vision” 3-D glasses worn by the audience, it was clear that Neil Young was taking his game to new and unprecedented levels. Unfortunately, this was a very brief artistic high that wasn’t going to last.