40

I Said Solo, They Said Acoustic

Neil Young Brings Le Noise to the Twisted Road

Neil Young spent much of 2010 giving concert audiences a preview of the new album he was recording in Los Angeles at the time with producer Daniel Lanois. As a renowned producer (and occasional solo artist), Lanois is best known for his work with a wide array of artists including Bob Dylan, U2, Peter Gabriel and Coldplay, and for occasionally collaborating with fellow avant musical deconstructionist Brian Eno.

But more than that, he is known for his electronic treatments on the albums he has produced for those artists and others, using the sort of effects like tape loops and echo that the producer simply refers to as “sonics.” The year 2010 proved to be one where Young fans would be learning a lot more about Daniel Lanois and his sonics.

For Le Noise, the album that was eventually released on September 28, 2010, these sonics are applied to his mostly electric guitar to produce a wall of feedback-laden sound the likes of which had never been heard on a Neil Young album before. The songs were mostly recorded at Lanois’s home in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles during a series of full moons (recording during a full moon has become a custom of Young’s over the years).

The album was originally going to be titled “Twisted Road,” but was finally released as Le Noise as an apparent nod to Lanois. Whether or not the album title is a clever tribute to the producer or not (Lanois equals Le Noise, get it?), in this case, the shoe certainly fits.

Twisted Road

As has become his standard operating procedure over the years, Young previewed many of the songs on the Twisted Road tour. With this tour, billed as a series of solo concerts, Neil Young fans once again probably expected an evening of acoustic music, heavy on favorites from albums like Harvest and Harvest Moon. While they did get some of that, the bulk of the shows were comprised of the new songs that ended up on Le Noise (as well as a few that didn’t make the final cut like “Leah”).

Neil Young performs at Bonnaroo 2011.

Photo by Mary Andrews

Here again, the Twisted Road tour found Young stretching boundaries by trying something new—which in this case meant playing the songs solo on a suitably cranked electric guitar, rather than on an acoustic.

However, his audiences—who had perhaps by now become more accustomed to expecting the unexpected at his concerts—responded much more favorably to the new songs than on past tours like the infamous 1973 Tonight’s the Night shows, and for good reason.

The new songs represented some of Young’s best songwriting in years, and indeed were a highlight of the shows (at least according to the mostly rave notices the shows received from critics). As word got out about his latest new artistic direction, concert posters and T-shirts sporting the catchphrase “I Said Solo, They Said Acoustic” began cropping up.

Not that all of the new songs were played with the amps cranked up, though. For two of the songs, “Love and War” and “Peaceful Valley Boulevard,” he strapped on an acoustic guitar. But this wasn’t your “Heart of Gold” folkie-sounding Young either. Both songs mirror the dark tone of the louder, feedback-heavy electric songs like “Walk with Me,” and also feature the signature Lanois sonic treatments.

But what is most striking about these songs is the simple, more direct approach of the lyrics, which again represent some of Young’s best songwriting in years, if not decades.

On “Walk with Me” he acknowledges the still fresh loss of friends in 2010 like Ben Keith and Larry “L.A.” Johnson with lines like “I lost some friends I was traveling with, I miss the soul and the old friendship,” while expressing both gratitude and a promise that “I’ll never let you down no matter what we do, if you’ll just walk with me” to those loved ones who remain.

“Love and War” is an antiwar song as the title suggests, but also has a more subtle and mournful tone than Young’s previous stabs at protest music like “Ohio” or the songs on 2006’s controversial Living with War album. Most interestingly, he occasionally seems to even acknowledge this with lines like “I sang for justice, but I hit a bad chord.”

On the almost shockingly confessional “The Hitchhiker,” Young takes this new lyrical forthrightness even further. In a rare moment of lyrical candor, he runs through much of his history—from the drugs to the failed relationships—in what has to rank as one of the most bluntly honest and personal songs he has ever written. It’s a stunning piece of work coming from an artist not known for such personal candor, and who has historically been notoriously reluctant to reveal his hand.

There is in fact a feel of creeping mortality in many of these songs, as well as a sense that Young may be trying to get his house in order.

When I Was a Hitchhiker on the Road, I Had to Count on You

If Sleeps with Angels—Young’s 1994 reaction to the death of Kurt Cobain—has been called the sequel to his dark masterpiece Tonight’s the Night, you could just as easily label Le Noise an extension of past work ranging from 1983’s Trans to 2005’s Prairie Wind.

To do so, however, would also be to sell it way too short. Le Noise is in fact the boldest-sounding, most artistically challenging record Young has made in a decade or more. It is also easily his best album in at least that long. As is so often the case with this artist, time will probably tell. But on an initial listen, Le Noise has the feel of a classic.

This is also an album that is best played very loud on a stereo system with a pair of speakers that can take it (and preferably somewhere where you won’t piss off the neighbors). Forget the iPod and the earbuds. There is simply no other way to properly experience how producer Lanois has added multiple sonic dimensions to Young’s guitar the way he does on Le Noise than playing it at maximum volume. This sucker needs to be turned up way loud.

Comparisons to the infamous syntho-pop of Trans are probably inevitable, though. Lanois’s electronic treatments of Young’s massively cranked, white electric Gretsch guitar manifest themselves nearly as often in the whirring and clicking noises heard at the end of “Walk with Me” as they do in the deep-humming, speaker-rattling feedback of “The Hitchhiker.” On the latter, Young even manages to sneak in a line from “Like an Inca”—a song from, you guessed it, Trans.

As it turns out, the connection between “Like an Inca” and “The Hitchhiker” is no coincidence. Although some fans may recognize “The Hitchhiker” as a song Young often played live during the Harvest Moon era, it actually dates back much further.

Originally recorded as “Like an Inca (Hitchhiker)” during a full moon on August 11, 1976, at Indigo Studios in Malibu Canyon, the original acoustic version was part of a particularly fertile session that also produced gems like “Will to Love” and the original solo acoustic masters for songs like “Pocahontas,” “Powderfinger,” “Captain Kennedy,” “Ride My Llama,” “Campaigner,” and others. Many of these original recordings can be heard on bootleg copies of the unreleased album Chrome Dreams, but nearly all of them eventually made their way to officially released albums like American Stars and Bars and Rust Never Sleeps.

As for the original “Like an Inca (Hitchhiker),” this would eventually end up splitting into two songs: “Like an Inca,” which was released on 1983’s Trans, and “The Hitchhiker,” which makes its official debut on Le Noise.

Then Came Paranoia and It Ran Away with Me

The eight songs on Le Noise also find Young at his most lyrically personal and introspective since Prairie Wind.

On the aforementioned “Walk with Me” and “Hitchhiker,” as well as on “Sign of Love” and “Love and War,” he reflects back on his life—and even questions some of his past decisions and behavior—before seeming to finally find a tentative sort of peace within himself.

The most obvious and fascinating example of this, again, is “The Hitchhiker.” Set against a howling backdrop of fuzzed-out power chords and feedback, the song finds Young reciting a personal history that reads like the darkest, most forbidden entries from a personal diary.

In this remarkable song, he lists every drug he’s ever taken, name checks both Toronto and California, and even briefly revisits his relationship with Carrie Snodgress (“then we had a kid and we split apart, and I was living on the road, and a little cocaine went a long, long way to ease that heavy load”).

Young even confronts his early stardom in a way those most familiar with his history will instantly recognize (“then came paranoia and it ran away with me, I would not sign an autograph or appear on TV”). Following this five minutes of confession time, he ends by simply stating, “I don’t know how I’m standing here, living my life, I’m thankful for my children and my faithful wife.”

It’s probably not a coincidence that when Young performed “The Hitchhiker” at the 25th Anniversary of Farm Aid on October 4, 2010, he told the crowd of 35,000, “now you know my secrets” at the song’s conclusion.

Promotional poster for the 2010/2011 Twisted Road tour, where “I Said Solo, They Said Acoustic” became a mantra for lucky fans witnessing Neil Young perform new, mostly electric material without a band.

Courtesy of Robert Rodriguez

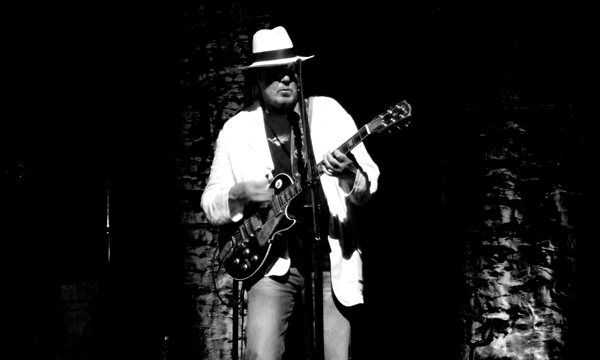

Neil Young on the Twisted Road tour in Clearwater, Florida.

Photo by Donald Gibson

I Hit a Bad Chord, but I Still Try to Sing About Love and War

“Sign of Love” is another song where Young expresses his feelings for Pegi (“when we’re just walking and holding hands, you can take it as a sign of love”). He also sneaks in a rather sweet nod to “Cinnamon Girl” here. During the line “when the music played, I watched you dance,” you’ll probably find yourself anticipating the power chords of that particular classic just as much I did.

In the same way that Lanois’s sonic treatments of Young’s blasting electric power chords add stunning new dimensions to that side of his sound (even without Crazy Horse or any eighteen-minute guitar solos), the two acoustic songs here serve as a reminder of just how good Young can be with the amps turned back down.

On both “Love and War” and “Peaceful Valley Boulevard,” Lanois’s recording brings out the deeper, darker bass tones as well as the lighter, more finessed flamenco tones of Young’s acoustic guitar playing in a way you’ve never quite heard before.

Even so, Lanois’s electronic “treatments” on the acoustic songs are another reason this album needs to be played extremely loud. On my own first listen, I found myself being jerked out of my seat wondering just what those odd noises I was hearing were. At one point, I even thought one of the neighbor cats was scratching on my window. The closest thing I could compare it to is the crackling fire heard on “Will to Love” from the American Stars and Bars album. Needless to say, these sonic treatments are about as organically real-sounding as it gets.

Of the two acoustic songs, “Love and War” is the more politically themed—although the antiwar sentiments expressed here are much lighter in tone than the bludgeoning over the head of Young’s 2006 firecracker Living with War. As with “The Hitchhiker,” he also waxes both autobiographical (“I sang songs about war since the backstreets of Toronto”) and even regretful (“I sang about justice and I hit a bad chord, but I still try to sing about love and war”).

“Peaceful Valley Boulevard,” on the other hand, is much broader in its subject matter. In the same way “The Hitchhiker” plays like a glimpse into his personal journal, “Peaceful Valley Boulevard” is filled with the sort of cinematic, historically minded imagery Young is simply unmatched at.

From scenes where “shots rang out” and “the bullets hit the bison from the train” in a Wild West Kansas City, to more modern images where an “electro cruiser coasted toward the exit, and turned on Peaceful Valley Boulevard,” the common thread between mining for gold and oil is God’s tears thundering down like rain.

Just when you least expected it, Young has delivered yet another masterpiece with 2010’s Le Noise. Even at this late stage of his career, his ability to create yet another game-changing record never ceases to astonish.

In that regard, he stands mostly alone amongst his musical peers of the sixties generation. Dylan and Springsteen are really the only other guys who even come close.