Framing Reality: A Case Study in Prison Theatre in Northern Ireland

David Grant

In June 2006, Frank McGuinness’s powerful evocation of the experience of Protestant soldiers from Northern Ireland during the First World War, Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme, was performed by prisoners in Hydebank Young Offenders Centre in Belfast. Beyond the frames of the world of the play and the production was the dominant frame of the prison itself. Based on interviews with key participants and the experience of working with the cast in the six months after the production, this article considers the impact and legacy of the project. Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme deals with one of the defining episodes in Northern Ireland Protestant culture. As such, it might have seemed too aligned to one side of the community to have enjoyed full support among a group of prisoners from both sides of the region’s cultural divide. Moreover, those familiar with the play, could not fail to be aware of the potential sensitivity within a prison of its homoerotic dimension. Experience was to show, however, that these anxieties were themselves functions of ‘the view’. This article recounts the use of a version of Boal’s Rainbow of Desire technique to explore the expanding perspective of the prisoner-participants and examines the experience of both them and the artistic team to suggest that the theatrical value system that both groups came to share, allowed the project to avoid the pitfall of becoming a public performance of punishment.

The Project

In June 2006, eight prisoners in Hydebank Young Offenders Centre in Belfast performed Frank McGuinness’s iconic account of Protestantism in the north of Ireland, Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme. In addition to the conventional concentric theatrical frames of the world of the play, the production and the venue, the visiting audience were also palpably aware of the additional framing provided by the prison itself.843 They experienced this in material form as they negotiated the security procedures before taking their seats and also in the presence with them in the performance space of prison inmates and staff. In addition to these multiple layers of reality, yet another frame was evidenced by the presence of television cameras, before, during and after the play. For me as a member of the audience, however, such was the conviction of the actors (a conscious but I hope forgivable pun) that all but the frame of the play were sublimated in the moment of performance. Reflecting on the experience afterwards, I found myself making connections between the world of the young volunteers in the trenches and that of their present-day peers on the stage, but as the action unfolded I was only intermittently aware of the production context. Based on interviews with key protagonists Mike Moloney, Dan Gordon, and Brendan Byrne, and the experience of six months spent working with the cast after the event, this article will consider the impact and legacy of the overall project (of which the production and eventually a BBC documentary are only the more visible parts) in relation to James Thompson’s idea of ‘the view’: that ‘we need over time to learn to look, not to be told what to look at’ and that ‘reflection needs a set of experiences against which judgment can be made’ (2003: 71-3).

The idea for the production came from Brendan Byrne of Hotshot Films, an independent production company based in Belfast. His initial interest was in a documentary about a rehearsal process and the idea for this to be of a production of the McGuinness play performed by young prisoners came later: but by his own account, once Observe the Sons became the basis of the project the idea sold itself. The BBC responded fairly readily to the proposal for four short films documenting the process. The prison authorities were also enthusiastic. They regularly receive requests from broadcasters to film in the prison and rarely agree, but they could see the inherent attraction of so challenging a project. Indeed, it was arguably this sense of challenge that made the proposal so attractive.

Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme deals with one of the defining episodes in Northern Ireland Protestant culture. As such, it might have seemed too aligned to one side of the community to have enjoyed full support among a group of prisoners drawn from both sides of the region’s cultural divide. Moreover, those familiar with the play, could not fail to be aware of the potential sensitivity within a prison of its homoerotic dimension. Experience was to show, however, that these anxieties were themselves functions of ‘the view’.

In Applied Theatre: Bewilderment and Beyond, Thompson articulates this concept through a series of anecdotes. He recalls a visit to the Grand Canyon and how, while he and his wife marvelled at the uniquely breathtaking vista, his infant children played in the sand by the road, unmoved by the epic spectacle before them. He relates this to his own indifference, when a teenager, to the remarkable topography of Edinburgh – a city that now enthralls him – and argues that we learn through a lifetime of experience to contextualize what we see. He concludes that the range of perspective of the young is generally more limited than that of older observers. I would add cultural experience and education as other factors that define the extent and nature of an individual’s view.

To apply this in my own case, although I had directed a play in Maghabery Prison in 1993, I had no direct experience of Hydebank Young Offenders Centre. I had developed a strong respect for the prisoners I had worked with in Maghabery, but in those pre-Ceasefire days it was easy to romanticize the entire prison population as politically driven. I made a point of not knowing what offences the prisoners I was working with had been convicted of, but imagined them all as having paramilitary pasts. I vividly recall my first meeting with them. I stood alone at one end of the large education room: they stood at the other end, clumped together, a phalanx of tattooed forearms. Suddenly one of them inched forward. ‘Mr Grant, we’ve just got one question for you. (Pause) You’re not going to shout at us, are you?’ They were clearly much more apprehensive than I was. Dan Gordon, who directed Observe the Sons, recounted a similar sense of ambiguity about his first exposure to the prison environment in an article for the Northern Ireland Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (NIACRO) newsletter:

What also bothers me is I’ve liked the people I’ve met so far. I don’t know who they are or what they’ve done and really I don’t want to. And I’m certainly not a victim so I don’t feel I have any right to judge – but when I meet them and talk to them I’ve liked them … all of them. It’s very confusing – they don’t have horns or tails or try to steal my watch, they just want to break the routine for a few minutes with talk … But when we talk – when the masks come off – I’m shocked by my ignorance and their ordinariness. Every day we interact on a human level – I know nothing other than what they tell me about how they feel about themselves and the worlds they know … I’m learning every day that people and life are a lot more complicated than I thought (16).

My own expectations of the Hydebank prisoners were, I realize now, just as contradictory. On one hand, I imagined that they would be mainly ‘hoods’ (young anti-social hooligans with a propensity for joyriding). On the other hand, I assumed that they would be strongly sectarian with paramilitary connections. Having worked in the centre on and off for six months, my view has broadened. The range of offences is much wider than I had imagined and levels of sectarianism are remarkably low – not least, I now understand, because many of the inmates are the principal targets of paramilitary punishment regimes. Nevertheless, Observe the Sons presented obvious difficulties. As Margaret Llewellyn-Jones has observed, for instance, ‘the iconographic significance of the donning of an Orange sash … will evoke different and potentially challenging responses’ depending on the context of the production (10). At the start of each performance of Observe the Sons, Dan Gordon addressed the audience explaining that the play contained ‘emblems’ and ‘language’, but with hindsight, I think this was more for the benefit of the guests than the prisoners. Apart from one quite performative episode during the rehearsal period, when a Catholic member of the cast refused to wear an Orange sash until he had permission from his mother, there was little evidence of sectarianism among the mixed cast. Dan and Mike Moloney (the coordinator of the project and Director of the Prison Arts Foundation) are both adamant that this was ‘never about the sash’ but part of an elaborate games-manship that characterized much of the rehearsal process. As his peers caustically commented, the prisoner concerned hadn’t asked his mother’s permission for his armed robbery! Similarly, the play’s treatment of sexuality was acknowledged in the rehearsal room but not fetishized. Although the cast, as the only openly homosexual member of the cast put it to me, ‘were not keen on the gay stuff’, the subject was far from taboo and a powerful tenderness was evident on stage.

What I imagined to be major obstacles, then, the production took in its stride. Far more significant was the institutional environment. Dan Gordon has attributed the success of the whole project to ‘a series of happy accidents’. Firstly, the Chief Security Officer at Hydebank turned out to be a ‘Somme fanatic’. He agreed to give a talk to the cast in the first week of rehearsals and they later noted – from the rushes of the Hotshot Films documentary for the BBC – how visibly moved he was by what he told them. Secondly, it proved possible to transform the somewhat sterile environment of the prison chapel where they rehearsed by use of camouflage netting which could be stowed in a duvet cover between sessions. A Brechtian half-curtain was also used to disguise offices at one end of the room.

The third fortuitous element was the casting process. More than a hundred and fifty prisoners saw a promotional DVD of Dan at the commemorative Somme Centre in which he appeared both as himself and as Red Hand Luke, a satirical loyalist character he plays on the popular BBC Northern Ireland comedy series, Give My Head Peace. Dan had been ambivalent about using this television persona, but the rushes of the documentary show that this provided an immediate point of contact for the prisoners who saw it. One hundred and twenty expressed initial interest as a result: fifty turned up to the prison gym for a briefing session. Of these, not all were eligible to participate for legal reasons: for example, because they were on remand and a television appearance might unfairly influence a future trial. In the end, however, twenty-five signed up for audition and eighteen actually came forward. In the audition process, the artistic team consistently referred to popular television parallels, coming up with the idea of Prison Idol. With various changes throughout the early weeks of the process, this eighteen became the core of the final company.

Dan’s fourth happy circumstance was the play itself, which required all the actors to be on stage throughout the performance. This allowed him to insist that they all listen in rehearsal all the time. The fact that the characters formed four distinct pairings also proved useful and the process became driven by competition between pairs. The analogy of prison cellmates was noted by one participant – when you’re locked up in a small room with someone, you have to get on. In retrospect, Dan ‘felt a great sense of disappointment’ that they never became one team. But the pairings produced some superb moments like one exultant ‘high fives’ at the end of a successful run of a scene.

Dan’s final explanation for the success of the production lay in his own background as a P.E. teacher. This enabled him to join in the rigorous military style physical preparation that began the process and to engage with the P.E. teachers on the prison staff. He understood the culture of the gym and respected it. In response to the question, ‘[h]ow do the practices of drama and theatre best engage with the systems of formalized power to create a space of radical freedom[?]’ (Kershaw, 36), Baz Kershaw has concluded that they have a greater chance of doing so when they ‘fully and directly engage with the discourses of power in their particular settings’ (49). It seems clear from the above account, that the success of Observe the Sons derived not least from the way in which the idea of the play made an impact on the prison authorities, most obviously in the person of the Chief Security Officer and in which the production style connected with the centre’s prevailing gymnasium culture.

Perhaps the greatest challenge in creating theatre inside a prison is the capacity of the institution to deaden the imagination. If the Benthamite ideal of a jail is the all-seeing panopticon, the vision thus provided is entirely literal, with little scope for metaphor or analogy. Mike Moloney recalled a moment when he was showing the mother and grandmother of one of the cast their son/grandson’s picture in First World War uniform, on display in the performance space after the show. They had clearly been moved by the play and were proud of their offspring, so Mike tried to engage them in an imaginative journey. ‘Do you see that soldier?’ he asked, and they played along. And then he asked if they saw their own boy. They shook their heads in sad denial. The idea of re-imagining him as other than a criminal was too great a leap for them to take.

James Thompson’s idea of ‘the view’ is helpful in understanding this situation. In the case of the mother and grandmother described above, they lacked a relevant ‘set of experiences’ to allow them to look with a significative eye. They needed the opportunity ‘to learn to look, not to be told what to look at’. Those of us whose daily lives are preoccupied with theatre often underestimate the extent to which we are required to frame and process a theatrical event, both as spectators and practitioners. Bert States’s pithy comparison of phenomenological and semiotic modes of understanding is instructive here:

If we think of semiotics and phenomenology as modes of seeing, we might say that they constitute a kind of binocular vision: one eye enables us to see the world phenomenally: the other eye enables us to see significatively … Lose the sight of your phenomenal eye and you become a Don Quixote (everything is something else). Lose the sight of your significative eye and you become Sartre’s Roquentin (everything is nothing but itself) (8).

Most mainstream theatre assumes its audience to have some sort of theatrical education, without much thought to how these theatrical sign systems are created, propagated and managed. One way of illustrating this, by analogy, is to look at the experience of a newcomer to the prison system. The prison enjoys its own rich semiotic system. The clothes that prisoners wear carry a wide extended meaning. Prisoners wearing polo-shirts and jeans are in standard prison issue. Those in sportswear are wearing their own clothes. But as was explained to me by Mike Moloney, the prison issue has the additional significance that these prisoners have probably little support or contact with the outside world. So, in a drama workshop I held in the prison shortly after the end of the production of Observe the Sons, when one of the participants drew attention to the new t-shirt being worn by another member of the group, this carried the additional meaning that that prisoner had had a recent visit. In fact, the t-shirt had been provided by one of the play’s professional production team, who had come to understand the psychological importance of prisoners being able to wear their own clothes.

Another powerful example of this prison semiosis occurred late in the rehearsal process. Unusually for non-prison staff, Mike and Dan were given permission to walk prisoners around the grounds without escort. In the final run-up to the production, Dan realized that one of the stage crew would be more valuable in the theatre than in the rehearsal room. He asked the prison officer on duty if he could walk the prisoner concerned across to the other building without waiting for another officer to be summoned. This was agreed to, provided that Dan took the prisoner’s identifying ‘T-Card’ with him. These cards are held by an officer in respect of any prisoner for whom he has responsibility at any given time. On Dan’s return, a member of the cast grew angry, castigating Dan for having become a ‘screw’. In that prisoner’s eyes, the powerful symbolism of the T-Card (what for Dan had seemed at most an administrative irrelevance), had transformed him from benign outsider to an integral part of the prison system.

If the view of artists working in the prison was altered through the process of working on the production, that of the prisoners also underwent change. By Dan’s account, the rehearsal process depended heavily on him demonstrating approaches to the performance, sometimes line by line. The prisoners lacked the experience and the terminological shorthand to translate the written text into performance without this kind of painstaking mediation. But they were extremely adept at negotiating the social context of the production. In particular, the presence of the documentary cameras created an unusual rehearsal dynamic. Part of the drama training process involved rigorous quasi-military physical workouts and Dan and Mike both commented on the total dedication that followed from the prisoners’ awareness that they were being filmed.

One episode illustrated the sophisticated understanding of the filming process that at least one prisoner developed. This cast member (the one whose mother and grandmother had been looking at his picture and who had temporarily refused to wear the sash) had been consistently the most difficult in rehearsal, regularly bridling against the discipline required by the process and eventually refusing to come down for rehearsal at all. Mike went to reason with him accompanied by the camera, but to begin with, the cameraman held back, recording sound only while Mike talked to the prisoner in his cell. Eventually, as negotiations reached an advanced stage, the camera tentatively invaded the prisoner’s private space. Clearly aware of the camera, but without directly acknowledging it, the prisoner reiterated the main points of his argument which we had already heard off-camera, demonstrating a subtle understanding of the editing process.

The combination of engaging in a drama-based process while simultaneously being filmed shattered the monocular perspective that constrains most prisoners. Instead of a tunnel-visioned pre-occupation with their release date, the play offered its participants a temporary imaginative respite, while the camera created an extended digital view – a sense of virtual perspective. One powerful example of this came early in the rehearsal process when some of the cast made a pop video. This proved crucial in building their confidence in the whole production process. As Dan and Mike put it, once they saw the finished product they knew that they could be made to look good.

Caoimhe McAvinchey has noted a similar phenomenon while working with women prisoners in England and Brazil as part of ‘Staging Human Rights’ (221-225). Her original role was to document a broadly-based creative project and her intention was to make herself as unobtrusive as possible. But her digital camera and laptop computer soon generated more interest among the prisoners than the substantive activities themselves. In fact, the prisoners’ evident interest in their own images became the catalyst for a collaboration with Jan Platun and Rachel Hale (a photographer and visual artist), ‘Handheld 3’, a project in the women’s wing of Hydebank in November 2006. In prison, one’s sense of oneself is necessarily circumscribed and the women prisoners in Belfast demonstrated a clear appreciation of the opportunity to create symbolic images of themselves using Polaroid photographs when I was among the guests invited in to see their work.

Observe the Sons of Ulster created similar opportunities for the participants to stretch their imaginations. I recall, as a member of the audience, the heightened symbolism of an early exchange between Craig and Pyper:

PYPER. Have you ever looked at an apple?

CRAIG. Yes.

PYPER. What did you see?

CRAIG. An apple.

PYPER. I don’t. I see through it.

CRAIG. The skin, you mean?

PYPER. The flesh, the flesh, the flesh.

CRAIG. What about it?

PYPER. Beautiful. Hard. White (104-105).

What struck me was not so much the homoerotic subtext, as the simple power of imagery – the possibility of the apple being something other than it was. For a few months, these prisoners, through the medium of the production, were allowed to discover a renewed sense of themselves–to look with a semiotic as well as a phenomenological eye.

In a workshop with most of the cast and crew, a few weeks after the final performance, I sought to explore this idea of extended perspective using a variant of Boal’s ‘Rainbow of Desire’ technique (Boal, 150-6). Boal developed this technique to ‘examine individual, internalized oppressions’ (Jackson in Boal, xviii) as distinct from the more public oppressions associated with his earlier development of Forum Theatre, but I have found it a useful rehearsal technique when applied to fictional situations. By engaging the group in an interactive process, I hoped I could avoid any resistance to more conventional discussion within a group that for the most part had had a bad experience of formal education.

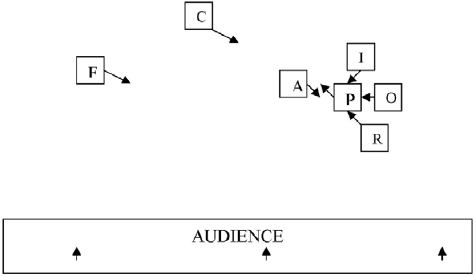

We restaged a moment towards the end of the play, just before the soldiers go ‘over the top’ to almost certain death, when the hard-line Orangeman, Anderson, hands Pyper, the play’s narrator, an orange sash. I asked the group to suggest different things that Pyper might want in that moment (his ‘desires’, however strong or weak these might be). At first, the actor playing Pyper was resistant to the notion that his character could be anything other than fully committed to his comrades – a fixity natural in someone who had evoked the moment before a series of audiences. But eventually the following additional ‘desires’ were teased out: Pyper’s desire to be his own man (I), his desire to conform to Orangism (O), his commitment to Craig (C), his commitment to his family (F) and his reluctance to be drawn into ‘Carson’s Dance’ (McGuinness, 163) (R). A striking feature of the discussion was the way in which many of the group quoted fluently and freely from the text, having clearly fully internalized it. In accordance with Boal’s methodology, all of these ‘desires’ were then represented by different members of the group and the actor playing Pyper engaged in an improvised dialogue with each, before arranging them in the performance space according to how he perceived their importance for his character. The improvisations revealed a strong sense of collective responsibility, which seemed to apply as much to the group of prisoners themselves as to the characters they were portraying.

Once the ‘Rainbow Image’ was created, many of the group were quick to comment on it. One prisoner noted that all the ‘Desires’ were pointing towards Pyper: another that he had placed the ‘family’ image very far away. I then noted that the Craig image, although at a distance was in Pyper’s eyeline and also the nearest element to the figure representing Pyper’s family: that Anderson stood with the sash between Pyper and his family, perhaps suggesting Pyper’s new sense of allegiance: that the figure representing Pyper’s reluctance to get drawn in was nearest the audience, echoing his character’s attitude in the play’s prologue: and that the figure representing his sense of independence was positioned nearest the figure representing his commitment to Craig. The group seemed fairly ready to accept these readings.

Key: P = Pyper: I = Desire to be his own man: O = desire to conform to Orangism: C = commitment to Craig: A = Anderson giving him the Sash: R = reluctance to get drawn in Carson’s Dance:

F = Commitment to Family

In preparation for the image theatre of the ‘Rainbow of Desire’, I took the group through a series of image-based exercises, including the ‘Image of the Hour’ (Boal, 112-3). This entails each participant enacting a simple mime, indicating what they would be doing at each hour of a typical day. Knowing more now about the system of ‘compacts’ that rewards prisoners for good behaviour with increasing levels of privileges, I would be able to understand more fully than I did then the significance of certain prisoners showing themselves playing video games, but I still think I rightly interpreted the high incidence of masturbatory images in the ‘wee small hours’, as a genuine part of the exercise rather than a commentary on the workshop itself. The fact was that these young men had become remarkably comfortable with drama-based modes of expression.

When I followed this exercise up by asking them to represent an image, hour-by-hour, of the best day they could remember, the results were predictably hedonistic, with the memorable exception of one young man who spent the entire exercise nursing a small child in his arms. I subsequently discovered that, like a remarkably high proportion of the 18-23 year olds in Hydebank, he was a father and that he had seen his daughter the previous week for the first time in several years. In subsequent meetings with him, it became clear that this was not something that he discussed with his peers. I found it all the more remarkable, therefore, that the drama exercise had created a safe enough space for him to demonstrate these feelings imagistically.

My intention had been that this workshop would be the start of a follow-up project with the Observe the Sons cast and crew, aimed at building on the extraordinary achievement of the production. But within weeks, in response to an escape attempt, the prison authorities vividly displayed their own point of view by transferring half of the cast to other prisons. I have no evidence that cast members were deliberately targeted and it is clear from talking to prison officials at various levels of authority that there was an exceptional sense of collective pride in the production. But that an emergency movement of 10% of the prison population included 50% of the cast of the play seems statistically remarkable. On one level, this simply reflects the over-riding importance of security within the prison system. The transferred prisoners also included two about to sit exams, but educational considerations carry little weight when security issues are invoked. But Mike Moloney has suggested to me that there is also an extent to which the prison system reacts, almost intuitively, against anything that encourages prisoners to feel part of a group. Isolation is an important instrument of control. As Baz Kershaw has observed in relation to his own work in prisons, ‘creative work… is customarily an unwelcome challenge to authority, an unpredictable disruption of norms’ (35).

There have been many important positive legacies of the production, however. For the duration of the production, all participants achieved ‘Enhanced Status’, giving them access to the maximum level of privileges. But since the production, each prisoner’s story has been different. Of the four cast members who remained in Hydebank, three withdrew from further drama activities, but one of these has been motivated by the production to pursue vocational training as a P.E. instructor. In a recent court appearance, one of the stage crew attracted a much lighter sentence than expected – a decision influenced, I understand, by a character witness from the production team. Another prisoner is now released and keen to seek further training opportunities in theatre. Of the prisoners transferred from Hydebank, one feels a strong sense of betrayal at his treatment by a prison service he believed he has served well through the production and this has undone much of the benefit of it to him. But another is actively applying to drama schools. Here is an extract from a personal statement he has written for one of his application forms:

I’ve found from doing the play that to look believable you just have to let yourself go and lose yourself in the performance, which at first, was very challenging. Doing the play has taught me a greater confidence in myself and also that I enjoy rising to the challenge. If I’m accepted into Drama School I hope to develop new techniques and evolve as an actor and a person. I believe in life you learn more about your character by challenging yourself and no doubt Drama School would do just that. I hope to learn how to drop the self-protecting barriers I have created for myself from having hard life experiences and to learn the ability to let go of my inhibitions and become a professional actor. I want to be a successful actor because I love the buzz you get when you see the anticipation on the faces of the audience and you can see them hanging on every word you say and making them feel just what your character is feeling. Then when you receive that standing ovation it is like no other feeling in the world. You feel so much satisfaction from knowing that the audience has enjoyed something you’ve put so much hard work into.

I find this statement very moving. It testifies to the life-enhancing impact of the production. And it also illustrates this prisoner’s extended ‘view’ of himself.

There are many ‘views’ addressed in this article. The ‘view’ of the prisoners who participated in the production can be seen to have changed, both through the experience of the event itself and the digital extension of that process in the presence of the documentary camera. The ‘view’ of the prisoners who did not perform, but who saw the play also changed in the respect that many showed for the performers. One actor acquired the nickname ‘Shakespeare’ on his prison landing, but the tone of delivery changed from sarcasm to appreciation once his fellow prisoners had seen the play. The view of the prison authorities also changed, best evidenced by the decision to allow the use of real bayonets on stage, but the widening of vision was short-lived and the longer-term value of the production was not realized.

The final point of view I want to consider is that of the wider public, in a number of its forms. James Thompson has suggested that ‘the popularity of certain forms of prison theatre could be understood as a response to the invisibility of the body of the prisoner in contemporary performances of punishment’ (61). He is concerned that however well intentioned, prison plays may serve as a contemporary ‘performance of punishment’, in the tradition of public hangings and the stocks and he questions the value system governing such events. For the audiences that attended performances of Observe the Sons in Hydebank, the quality of the work prevented this becoming an issue. That is, the event was subject to a theatrical value system, which made the prison context largely incidental. I believe that this is a particular feature of prison arts in Northern Ireland, where there is seamless connection with the mainstream theatre, exemplified by the involvement of an artist like Dan Gordon, who is at the pinnacle of the local professional arts establishment. The following comment by one drama student who participated in a workshop at Hydebank reinforces the importance of the immediate human connection that is possible within a live event:

I found it very surprising that such a friendly group of interesting and charismatic men could be in this institution. The workshop broke down my social stereotypes of young offenders’ institutions and has made me really interested in doing more projects like this.

What may prove more problematic is the reception of the BBC documentary being made about the production process. While the presence of the camera provided the prisoners an extended ‘virtual view’ by allowing them to imagine themselves being seen by un-known others, the actual transmission of these images will lack the human immediacy of the live theatre event. In part to prepare the cast for the experience of seeing the documentaries, a special screening of an edited version of the recorded performances of Observe the Sons of Ulster was held in the chapel of Hydebank Young Offenders Centre in March 2007, a full year after the rehearsal process began.

It is hoped by Mike Moloney that this experience of seeing themselves look good on screen will equip the participants to negotiate the aftermath of the broadcast of the documentaries themselves. Watching the performance again, this time having got to know some of the young men involved (that is, with my own ‘view’ broadened) I was struck by the fact that the authority figures mimicked by the characters in the play – the army officer and the preacher – are both shown shouting, while the words of the imagined Orange speaker at ‘the Field’ (the traditional destination of Belfast’s 12th July march) are delivered with equal virulence. I was reminded of a comment by one of my former students who spent some time working with two of the cast after they had been transferred to Magilligan Prison near Derry. He was struck by the prisoners’ evident need simply to talk to him. ‘No-one’, he concluded, ‘has ever listened to these guys, ever!’ His comment brings to mind the definition of oppression quoted by the founder of Playback Theatre, Jonathan Fox – that being oppressed is having nowhere to tell your story (Fox, 6).

Be that as it may, the means by which the story is told is also crucial. It seemed to me, both watching the production and observing the participants at various times thereafter, that the indirect telling of that story through McGuinness’s play had a profound impact on all those involved, usually for the good. The more direct retelling of their story through four thirty-minute documentaries is a different matter entirely. It will inevitably objectify the participants and runs the risk of distancing the television viewers from the humanity they and those in prison share. On the other hand, if the documentary can capture not just the prestige and excitement of the production itself, but also the problematic diversity of its legacy and aftermath, then I think the full story of Observe the Sons of Ulster at Hydebank may still be served.

Works Cited

Bentham, Jeremy, Panopticon (Preface). In Miran Bozovic (ed.), The Panopticon Writings (London: Verso, 1995).

Boal, Augusto, The Rainbow of Desire. Translated & Introduced by Adrian Jackson (London: Routledge, 1993).

Fox, Jonathan, Acts of Service: spontaneity, commitment, tradition in the nonscripted theatre (New Paltz, NY: Tusitala Pub, 1994).

Gordon, Dan, ‘Thinking about Prison’ NIACRO News 14 (Spring 2006).

Grant, David Unpublished Interview with Dan Gordon and Mike Moloney. Belfast, 22 June 2006.

---, Unpublished interview with Brendan Byrne. Belfast, 28 June 2006.

Kershaw, Baz, ‘Pathologies of Hope in Drama and Theatre’ in Michael Balfour, ed., Theatre in Prison: Theory and Practice (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2004).

Llewellyn-Jones, Margaret, Contemporary Irish Drama and Cultural Identity (Bristol: Intellect, 2002).

McAvinchey, Caoimhe, ‘Unexpected Acts: Women, prison and performance’ in Michael Balfour and John Somers, eds, Drama As Social Intervention (Concord, ON: Captus Press Inc., 2006).

McGuinness, Frank, ‘Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching towards the Somme’ in Frank McGuinness: Plays 1 (London: Faber, 1996).

O’Toole, John, The Process of Drama, (London: Routledge, 1992).

States, Bert O., Great Reckonings in Little Rooms, (University of California Press, 1985).

Thompson, James, Applied Theatre (Bern: Peter Lang LG, 2003).

---, ‘From the Stocks to the Stage: Prison Theatre and the Theatre of Prison’ in Michael Balfour, ed., Theatre in Prison: Theory and Practice (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2004)

Extract From: Performing Violence in Contemporary Ireland, edited by Lisa Fitzpatrick (2010)

Cross Reference: McGuinness essays and those on Marie Jones

See Also: Theatre and Northern Ireland