Physiology, PER, Spirals and the Neurology of Change

This chapter explains some of the physiology and neuroscience that has been instrumental in the development of the Lightning Process. I’d recommend that you read it even if you have an aversion to science, as it’s written for the layman and I’ve found that a deeper understanding of the science behind the Lightning Process can be very valuable in making sense of how this powerful change process works.

Let’s start by looking at two physiological processes that cause trouble and can be helped by the Lightning Process: the Physical Emergency Response and the Destructive Spiral. Learning about them will make it easier to understand how people became so stuck in their lives and health and how, through using the Lightning Process, they were finally able to break through that stuckness, even if their problems were of a very physical nature.

The information that follows is a relatively brief introduction to the subject, but it is discussed in much more detail during the Lightning Process seminar.

This is something that many people are initially confused about, which isn’t surprising as the answer only becomes clear when you have a fairly in-depth understanding of how the human body works.

This is when the body experiences an emergency or threat to its safety and wellbeing, which could include:

The body then naturally produces the PER to deal with the threat and to find a way to recover or stay safe. There are a number of key ways that the PER affects the body. It stimulates the sudden:

This is exactly what needs to happen to help us deal with the threat.

The easiest way to think of this is to consider ‘normal life’ thousands of years ago, when we lived close to dangerous wild animals. Imagine that a tiger appears. We need to either:

Both these actions are prepared for by the activation of the PER, which is designed to deal with threats. It prepares us for flight or fight and allows the body to channel all its energy into the muscles of the arms and legs, into making the heart beat faster and stronger, into pumping the blood more quickly through the body (by increasing the blood pressure) and into making lots of blood sugar available and ready to be burned by the muscles as fuel. These changes are all controlled by the sympathetic nervous system.

There is much less of a need in this crisis moment to do cave painting, digest, cook food or even heal yourself (these activities are all controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system or PNS). These things would waste precious energy and resources that need to be fully available for the vital job of escaping or beating the danger. A few minutes later, one of the following things will have happened:

If either one or two of the above has occurred, then the danger has now passed and you can begin to calm down, tend to your wounds, nurture yourself and recover from your experience. This means that you can switch off the PER, quiet down the SNS and let the PNS take over.

This way of operating causes modern-day humans a problem. Unfortunately, most of the threats we encounter are not like tigers. They don’t come along, require physical activity from us and then get resolved in this relatively rapid way. Many tend to be things that would be completely inappropriate to respond to physically (by fighting or running away), such as viruses, pollution, mortgages, waiting in queues, dealing with bosses or customers, etc.

They tend to be situations that don’t resolve rapidly, i.e. pollution and bosses don’t just go away, mortgages have to be paid every month for 20-plus years and so on. We respond in this way because that’s how we are designed to respond.

So the PER primarily does this by giving our muscles an extra burst of speed and strength and affecting the nervous system’s synapses (which we’ll discuss in more detail later in this chapter) and neurotransmitters. Temporarily, this is an excellent solution for dealing with most threats, but unfortunately long-term arousal of this system has long been known to have a detrimental effect on many other body systems18, causing disruption to the normal workings of our:

Let’s briefly consider what each of those body systems does, in order to see the potential effects of a PER activation.

The immune system is a key system of the body and has an important role in supporting the way all our other body systems work. It has many important functions, including recognizing, dealing with and removing:

There are two possible extremes of immune dysfunction:

As you can see from this list, any problems in this important system will have an effect throughout all the other body systems.

The muscular system, according to some experts, should be viewed as the most important system of the body, simply because it is the main user of energy in the body. As a result, many of the body’s support systems (blood, waste disposal, communications, etc.) are dedicated to keeping the muscles working well.

When the muscles don’t work well, not only can we no longer move ourselves as we would want to, it also puts an added strain on these core support systems. As movement itself is vital for pumping blood through the veins and fluid in the tissues back towards the heart, poor mobility puts more strain on the heart and circulatory systems.

Again, as you can see from this, any problems with the muscular system have an impact throughout all the other body systems.

This system has a number of important functions. The most obvious is, of course, to bring nutrition into the body. Any problems in this system will, therefore, naturally have a major effect everywhere else. Its other functions include a role:

This includes the brain, the spinal cord and all the nerves of the body. Their primary job is to ensure that there is good communication between the brain and all areas of the body, in both directions. In something as complex as our bodies, any small disruptions in the way this very sensitive system works can have massive consequences.

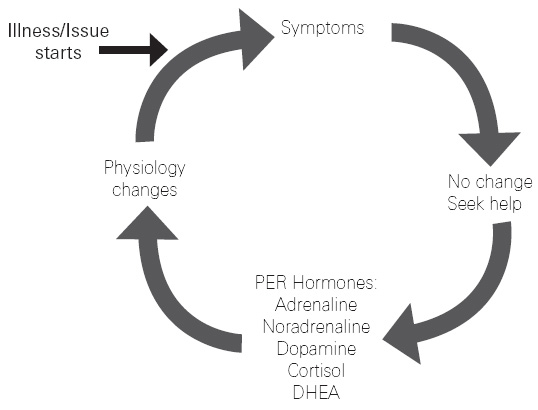

Having understood the PER, and the importance of these systems, this allows us to make sense of the Destructive Spiral or, as we also call it, the ‘Physiological Catch 22’. This is one of the important elements of the Lightning Process. It came from having discussions with thousands of people, with many suffering from chronically stuck conditions, about the course of their illness. In these discussions, I found they had experienced some variation of the following downward spiral:

The cycle of illness

You could compare this ‘Physiological Catch 22’ to the physics that affect someone who’s learning to walk on a tightrope. If they start to sway too far off balance to the left, their body naturally tries to save them from falling and compensates by swaying them to the right. Unfortunately, this movement only serves to throw their balance too far to the right and, before they know it, they’re swaying wildly from side to side. Once it starts it’s very difficult to stop. With each attempt to prevent themselves from falling, regaining their balance becomes more and more difficult.

An additional element can naturally be added to this spiral once it’s been physically set in motion by the biochemical response outlined above. This is the added effect that often follows due to the emotional distress of being unwell and all the questions and uncertainties that can arise about one’s future. In the vast majority of cases, the emotional overlay, which does make things worse, is secondary to the original threat that started the spiral off in the first place. This is key to the understanding of why certain diseases, including CFS/ME, should be viewed as primarily physical in nature, although they can be helped by a body–brain–mind approach.

Understanding some of the physical processes that occur in response to ill health shows us how managing and restoring health is complicated. It also becomes clear that a training programme such as the Lightning Process – which teaches you how to positively influence these physical processes – can open up a route to recovery from serious physical or psychological illness.

Reading the previous explanation might lead you to think that the Lightning Process is a method for reducing adrenaline, but this is, actually, a simplification of a quite complex situation. In fact, in some cases, this long-term overstimulation of the PER and its related hormone system adds a further level of complexity to that PER/illness cycle. The overproduction can then lead to an exhaustion of the glands that produce these important hormones, resulting in unusually low levels. This can have a different but equally damaging effect on the body.

In fact, although adrenaline, cortisol and the other hormones released by the PER are important in many but not all conditions, it is not an overproduction of these hormones, but a ‘dysregulation’, i.e. poor regulation, that is the key problem.

Due to the way that the various hormonal systems within the body interrelate, a dysfunctional production of one hormone almost invariably has an effect on the production of other hormones, which means the physiology can become even more complicated.

In CFS/ME, for example, research shows that in some cases you can see high levels of adrenaline and cortisol; in others, levels are low, or there are huge fluctuations of the levels. Consider that:

This means that accurately measuring the levels is always going to be hard to do and that a reading will only be valid for a brief period of time19.

The key word in all of this is ‘dysregulation’, which brings us back to our osteopathic philosophy: ‘When the body isn’t doing what it’s designed to do, something won’t work properly as a result’. In order to have good body function we need to improve the regulation of the production of these powerful hormones.

And finally, it’s also important to keep in mind that, although it is a very influential physiological problem, the Destructive Spiral is just one of the elements of some illnesses and not the only factor addressed in the Lightning Process.

This is the ability of the brain to rewire itself and it forms a vital element of the Lightning Process. Much of the original thinking into how the brain learns has been done by Nobel prize-winning luminaries such as Edelman and Kandel, and their work gives us a useful insight into why the Lightning Process works so rapidly and effectively.

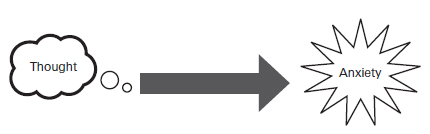

In recent decades, there has been a massive shift in how the brain is perceived. Originally, it was thought to be like a circuit board in which the wire-like nerves were built to perform a function and then stayed doing that until our brains got old or died. This idea has now been replaced by the modern idea in neuroscience that the brain is considered to be ‘plastic’. This means it has the ability to grow and develop in response to how it is used. So the more you stimulate a particular neural pathway, the better it works, the quicker a signal travels down that pathway, and the more it develops connections with other parts of the brain. It seems that the nerve pathways with the most connections influence more of the other parts of the brain, and so affect you and your life the most. It’s like the difference between trying to get somewhere using a country track or the entire multilane motorway system. Look at the following diagram to see how the pathways in the brain work.

A single thought or connection creates a particular experience

The thoughts create a signal that is transmitted along the nerve cells in the direction of the arrow. Once the signal has travelled all the way to the end of this particular pathway it will create (in this example) the feelings and experience of anxiety.

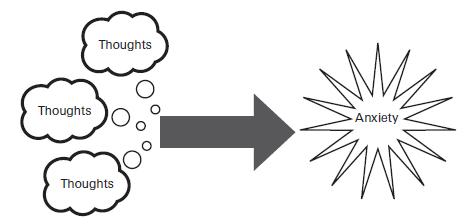

In the following diagram, additional thoughts have started to trigger that anxiety. This extra usage results in a ‘strengthening’ and increase in speed of this pathway, and therefore it becomes easier and easier to produce the feelings of anxiety every time.

Multiple thoughts or connections more easily trigger an experience

If you are someone who is used to anxiety in your life then the pathway that is responsible for the feelings of anxiety will be very well developed and fast, and it will also have lots of connections to other parts of the brain. The more connections a pathway has, and the more it’s used and triggered, the faster it will become, in the same way that a fast motorway with good links to lots of destinations will be used more than one that goes to fewer places.

This means that even the least consequential events can activate that pathway. For example, when someone with a highly developed anxiety pathway sees someone who looks very calm, it may remind them of how they hardly ever feel calm, and it will be enough to instantly trigger their anxiety pathway and give them feelings of anxiety.

They may see a soap opera on TV and, because one of the characters in it is worrying about their daughter, it may trigger their anxiety about their own child.

They may see a person in a shop who reminds them of a mean teacher they used to know, and that may trigger their anxiety.

In this way, many things start to connect to and fire off this anxiety pathway and, because the brain grows in response to how much it is used, it becomes like a superhighway in your nervous system and runs very fast and very effectively. And this is the mechanism behind how people can experience powerful feelings of anxiety, instantly, as a result of the slightest trigger.

Consider another example. Imagine a woman who had just had a miscarriage and lost her baby.

The next time she went into town, what would she see everywhere?

Babies.

And what shops would she notice?

Baby shops.

And if there weren’t any baby shops in that part of town, what would she notice about her shopping experience?

That there weren’t any baby shops.

If she saw people who were about 60 years old, how would that remind her of her loss?

They probably have grandchildren, which reminds her of her lost child.

In this scenario, the recently developed pathway related to the miscarriage is taking her into experiencing a deep sense of loss, but unfortunately the brain is making millions of connections from all sorts of random bits of information, like seeing ‘elderly people’, directly into the loss pathway, so it gets triggered all the time. This exercising of that particular set of nerve pathways in the brain makes them much easier to activate (this is covered in more depth in the next section), and the ‘thoughts’ travel quicker and more frequently down that pathway triggered by the bad feelings.

This may make you think that if you’ve got such a well-rehearsed ‘bad’ neurological pathway, triggered by even the slightest thing, then the situation is hopeless. Far from it. This ability of the brain to learn is key to your route to success.

When people learn to apply the Lightning Process they begin to divert the direction that pathway runs. Each time they use the Lightning Process they re-route that ‘bad’ pathway. What they, specifically, are doing is cutting out the portion of the old pathway that leads to the problem destination, and instead rejoining it up to a new section of the brain’s ‘motorways’ that heads in the direction they want to go.

This re-routing means that, from then on, every time those old pathways are triggered they now activate a completely different pathway. This new pathway is triggered by the same events as before, but now it leads them into a different part of the brain that is smarter and can make better choices.

If you left school some time ago, there are probably all sorts of subjects that you learned, such as long division, algebra or maybe a foreign language such as French or German, which you haven’t used much since. When you are suddenly presented with an opportunity to use those long-forgotten skills, what happens? Your brain feels ‘rusty’ as you try to remember the formula for how to do these things, or the words that you learned long ago for ‘punctured tyre’ or ‘run out of petrol’ in French.

You find yourself really grappling with your brain to try and find this information; you notice it’s not that easy to access now. This is a pathway which you haven’t used for a long time, and, because the brain is ‘plastic’, when you don’t use pathways, they degrade and slow down.

In olden times in the UK, long before cars and trucks, there used to be a very important network of well-used and well-maintained roads, used by drovers to herd their cattle to market. With the advent of motorized transport, however, people didn’t herd their cattle along these paths anymore. Instead, they took their livestock to market in trucks and trains, and the pathways became overgrown with weeds and washed away by rain. So now, even if you look really hard, you can barely find them.

This is exactly what starts to happen in your brain as you apply the Lightning Process. The very first few neurones in those old pathways, which used to produce the negative feelings or unuseful behaviours or physiological responses in your life, are still being triggered. Only now they are quickly re-routed to new areas of the brain that can produce better responses for you. The old parts of the pathway, the bits that actually produced the negative feelings, don’t get used in this new pathway and so start to slow down and degrade. Even if those pathways have been very well established, research into brain function and learning suggests that they can change quite rapidly. There are two main reasons for this:

This is why it’s so essential to use the Lightning Process appropriately, remembering that it is not a therapy or treatment but a re-education – a learning process that occurs not just during the seminar but afterwards. If you learn it but only apply it occasionally, or for a brief period of time, then the results won’t be that good. This simply will not give your brain enough time, or consistent input, to bed in these new pathways, and there is a good chance you will once again be re-energizing the old unhealthy pathways that you actually need to sedate.

From my discussions with the small group of people who get few or variable results from learning the Lightning Process, this seems to be most commonly missed in their application of the training. If, having read this book, you choose to learn the Lightning Process, please keep in mind that you need to give your brain a chance to establish the new patterns, and let the old ones fade away. This is essential if you wish to replicate the success reported by others. After all, that’s what they had to do to get the results that they got.

The changes that occur in neuroplasticity fundamentally affect one vital element of the nervous system: the nerve cells and their synapses. An understanding of what these are, and how they work, helps deepen our knowledge about how change occurs, and why sometimes the wrong pathways can get installed.

The nerve cells are long thin cells which can be considered to be the electric circuits, or wires, of the nervous system. When they are stimulated at one end they send an electrical signal all the way down to their other end. Here, there is another nerve cell, waiting to carry the signal onwards, but separating these cells is a tiny gap – the synapse. The synapses work like switches in an electrical circuit. They allow the nervous system to regulate whether a signal travels the entire length of the nerve pathway or not. This is important because, in order to have any effect, the signal needs to reach the end of the nerve pathway, but on that journey it has to cross a number of synapses.

When the signal reaches a synapse, one of two things will happen. It will either be transmitted further on, carried over the gap by chemicals called neurotransmitters, or the signal won’t go any further.

One easy way to understand this is to think of synapses as being similar to a wall that you can only climb over if you are tall enough (a strong signal) and small children (small or weak signals) will be prevented from climbing it (can’t cross the gap).

But synapses are a bit more complicated than this. First, the height of the wall can be changed by many different influences, such as how recently the nerve has been fired, how often you fire it on a daily basis, what your diet is like, etc.

This can mean that sometimes the height of the wall can be altered so much that it even stops tall adults (strong signals) from getting over it (crossing the synapse). This is why, when we get dressed in the morning, initially we feel our clothes against our skin, but soon after the synapse level changes and for the rest of the day we are mostly unaware of the feeling of our clothes.

Sometimes the height of the wall can be much lower than it should be. This results in small children (weak signals) getting over it easily. We can then have the situation where signals which would normally get stopped at a synapse get to travel all the way to the end of the pathway, triggering a sensation, such as pain, inappropriately.

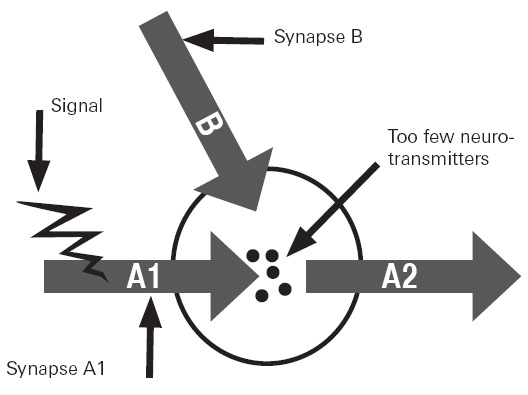

Second, there are many synapses where more than one nerve pathways meets. Imagine a synapse where pathways A and B both join. The signal from pathway A may not be strong enough to jump across the synapse (figure 6.1) but, when it joins with the signal from pathway B, the combination may be enough to trigger the signal onwards along pathway A (figure 6.2). Again, this creates a stronger result than you might expect from pathway A’s weak signal.

Both these scenarios are active in many of the conditions for which people use the Lightning Process. Fortunately, through the phenomenon of neuroplasticity, the synaptic sensitivity can be reset relatively easily and new pathways become dominant.

In the next chapter we’ll explore some of the founding principles of the Lightning Process.

Figure 6.1 A ‘weak’ signal may produce too few neurotransmitters to be able to jump across a synapse.

Figure 6.2 Neurotransmitters from different nerves may join together to allow the signal to cross the gap and continue along the pathway.