PRINCIPLE #2

SHAPE IDEOLOGY

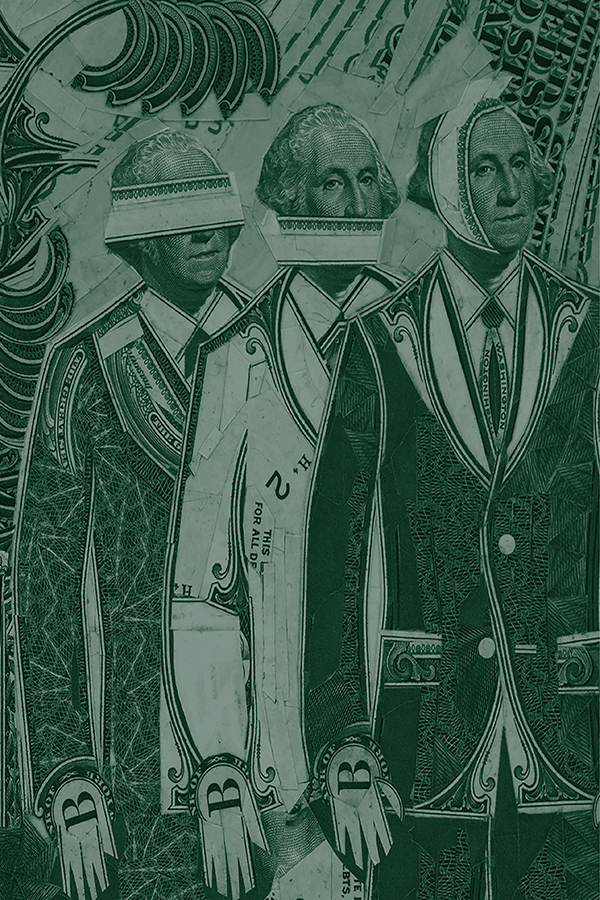

THERE HAS been an enormous, concentrated, coordinated business offensive beginning in the ’70s to try to beat back the egalitarian efforts that went right through the Nixon years.

You see it in many respects. Over on the right, you see it in things like the famous Powell Memorandum—sent to the Chamber of Commerce, the major business lobby, by later Supreme Court justice Powell—warning them that business is losing “control” over the society, and something has to be done to “counter” these forces.

The Powell Memorandum said that the most persecuted class in the United States is the capitalist class. The owners, the very rich, were totally persecuted. Everything’s been taken over by raving leftists—Herbert Marcuse, Ralph Nader, the media, the universities—but we have the money so we can fight back. And what we have to do is use our economic power to save what he would call “freedom”—meaning our power.

Of course, he puts it in terms of a defense, “defending ourselves against an outside power.” But if you look at it, it’s a call for business to use its control over resources to carry out a major offensive to beat back this democratizing wave.

EXCESS OF DEMOCRACY

At the liberal international end there was pretty much the same reaction. The first major report of the Trilateral Commission is concerned with this. It’s called The Crisis of Democracy. The Trilateral Commission is liberal internationalists from the three major industrial capitalist entities—Europe, Japan, North America. The complexion of it is illustrated by the fact that the Carter administration was drawn almost completely from their ranks—so that’s the opposite extreme within the political spectrum.

Now, they were also appalled by the democratizing tendencies of the ’60s, and thought, “we have to react to it.” They were concerned that there was an “excess of democracy” developing. Previously passive and obedient parts of the population—women, young people, old people, working people—what are sometimes called “the special interests”—were beginning to organize and try to enter the political arena. They said that imposes too much pressure on the system. It can’t deal with all these pressures. So, therefore, they have to return to passivity and become depoliticized.

They were particularly concerned with what was happening to young people, who were in the forefront of what was happening in the ’60s. The young people are getting too free and independent. The way they put it, there’s a failure on the part of the schools, the universities, the churches—the institutions responsible for the “indoctrination of the young.” Their phrase, not mine. We have to have what they called more “moderation in democracy,” and then things will be fine.

The Trilateral Commission liberals went on to offer measures to reinstitute better indoctrination to control the press, drive people back into passivity and apathy, and let the “right” kind of society develop. Across this spectrum you have various proposals they’ve implemented, and the changes in the economy that have been orchestrated helped provide means to carry out these measures.

EDUCATION AND INDOCTRINATION

It’s hard to establish direct cause/effect relationships, but it’s pretty hard not to see the general tendencies. So take, say, indoctrination of the young. From the early ’70s, you begin to see a number of processes under way to control college students. If you remember that time, right after the invasion of Cambodia, the country was blowing up. The colleges were closed. People were marching on Washington, and so on. And this control takes many forms. College architecture changed. New college architecture from that period (this, incidentally, is international) was consistently designed to avoid places where students can congregate. So, lead them down alleys or something, but let’s not have things like Sproul Hall in Berkeley, where students can get together and do things.

Since the ’70s college tuitions have started to climb, by now to ridiculous levels. Again, I don’t think we have documents to show that this was specifically planned, but you can see the consequences—for one thing it deprives large parts of the population of the option of higher education. But even those who are able to go through it, most of them end up trapped by debt. If a student comes out of college with $100,000 in debt, they’re trapped. There are very few options they can pursue. And the debt is structured so that they can’t pay it, you can’t go bankrupt, it’s not like a business debt or a personal debt. It’s hanging over your head for the rest of your life, they can garnish your Social Security. So you’ve got to devote yourself to subordination to power.

Pretty much the same thing is happening in K–12. The tendency in K–12 is reducing education to mechanical skills, and undermining creativity and independence—both on the part of teachers and students. That’s what “teaching to the test” is, “No Child Left Behind,” “Race to the Top.” I think these should be regarded as methods of indoctrination and control. Of course, one of the other ways to do that has been to simply reduce or eliminate free education.

The rise of the charter school system is also a very thinly disguised effort to destroy the public school system. Charter schools are a way of drawing public funds into private institutions, which will undermine the public school system. You don’t get better performance even with all the advantages and so on, and that’s happening across the board. So destroy public institutions.

There was an article in the New York Times quoting some doctors who give drugs to children in impoverished areas to try to improve their performance, knowing perfectly well that there’s nothing wrong with the children—there’s something wrong with the society. In fact, the way they put it, we as a society have decided not to modify the society but to modify the children. These are kids coming from impoverished areas, underfunded schools, and so on. They don’t do well so, therefore, we pour drugs into the children. It’s not quite the case that we as a society have decided on that—the masters of the society have decided on that.

CONDEMNATION OF CRITICS

This notion of being “anti-American” is quite an interesting one—it’s actually a totalitarian notion—it isn’t used in free societies. If someone in Italy criticized Berlusconi or the corruption of the Italian state, they’re not called “anti-Italian.” In fact, if they were called anti-Italian, people would collapse in laughter in the streets of Rome or Milan. In totalitarian states the notion is used. In the old Soviet Union, dissidents were called “anti-Soviet”—that was the worst condemnation. In the Brazilian military dictatorship they were called “anti-Brazilian.” But these concepts only arise in a culture where the state is identified with the society, the culture, the people, and so on. So if you criticize state power—and by state I mean generally not just government but state corporate power—if you criticize concentrated power, you’re against the society, you’re against the people. It’s quite striking that this is used in the United States, and in fact as far as I know, we are the only democratic society where the concept isn’t just ridiculed. And it’s a sign of elements of the elite culture that are quite ugly.

Now it’s true that in just about every society, critics are maligned or mistreated. In different ways depending on the nature of the society, like maybe in the old Soviet Union in the ’80s they would be imprisoned, or in El Salvador at the same time dissidents would have their brains blown out by US state-run terrorist forces. In other societies critics are just condemned, they’re vilified and so on. I mean, that’s normal, to be expected, and in the United States, one of the terms of abuse is “anti-American.” There’s an array of terms of abuse, like “Marxist,” but it doesn’t matter really, it’s a very free society. With everything that you can criticize it remains in many ways the freest society in the world. There’s repression, but among relatively privileged people, which is a big majority of the population, you have a very high degree of freedom. So if you’re vilified by some commissars, who cares, you go on—you do your work anyway.

THE NATIONAL INTEREST

For Powell on the right, it’s “we’ve got the money, we’re the trustees, we’ll impose discipline,” and so on. For the liberals it’s softer means, but we have to do the same thing. In fact the Trilateral Commission actually argued that the media are out of control, and if they continue to be so irresponsible government controls may be necessary to keep them in line. Anyone who’s looked at the media knows that they were so conformist it’s embarrassing. But it was too much for the liberals, on occasion doing something they didn’t like.

If you look at their study, there’s one interest they never mention—private business. And that makes sense—they’re not a special interest, they’re the national interest, kind of by definition. So, they’re okay. They’re allowed to have lobbyists, buy campaigns, staff the executive, make decisions—that’s fine—but it’s the rest, the special interests, the general population, who have to be subdued.

Well, that’s the spectrum. It’s the kind of ideological level of the backlash. But the major backlash, which was in parallel to this, was just redesigning the economy.

POWELL MEMORANDUM, 1971,

and other sources

Powell Memorandum, Lewis F. Powell Jr., 1971

DIMENSIONS OF THE ATTACK

No thoughtful person can question that the American economic system is under broad attack. This varies in scope, intensity, in the techniques employed, and in the level of visibility . . .

SOURCES OF THE ATTACK

The sources are varied and diffused. They include, not unexpectedly, the Communists, New Leftists and other revolutionaries who would destroy the entire system, both political and economic. These extremists of the left are far more numerous, better financed, and increasingly are more welcomed and encouraged by other elements of society, than ever before in our history. But they remain a small minority, and are not yet the principal cause for concern.

The most disquieting voices joining the chorus of criticism come from perfectly respectable elements of society: from the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians. In most of these groups the movement against the system is participated in only by minorities. Yet, these often are the most articulate, the most vocal, the most prolific in their writing and speaking . . .

TONE OF THE ATTACK

. . . Perhaps the single most effective antagonist of American business is Ralph Nader, who—thanks largely to the media—has become a legend in his own time and an idol of millions of Americans. A recent article in Fortune speaks of Nader as follows: “The passion that rules in him—and he is a passionate man—is aimed at smashing utterly the target of his hatred, which is corporate power . . .”

THE APATHY AND DEFAULT OF BUSINESS

. . . American business [is] “plainly in trouble”; the response to the wide range of critics has been ineffective, and has included appeasement; the time has come—indeed, it is long overdue—for the wisdom, ingenuity and resources of American business to be marshalled against those who would destroy it.

RESPONSIBILITY OF BUSINESS EXECUTIVES

. . . The overriding first need is for businessmen to recognize that the ultimate issue may be survival—survival of what we call the free enterprise system, and all that this means for the strength and prosperity of America and the freedom of our people.

A MORE AGGRESSIVE ATTITUDE

It is time for American business—which has demonstrated the greatest capacity in all history to produce and to influence consumer decisions—to apply their great talents vigorously to the preservation of the system itself.

The Crisis of Democracy:

Report on the Governability of Democracies to

the Trilateral Commission, 1975

THE VITALITY AND GOVERNABILITY

OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY

The 1960s witnessed a dramatic renewal of the democratic spirit in America. The predominant trends of that decade involved the challenging of the authority of established political, social, and economic institutions, increased popular participation in and control over those institutions, a reaction against the concentration of power in the executive branch of the federal government and in favor of the reassertion of the power of Congress and of state and local government, renewed commitment to the idea of equality on the part of intellectuals and other elites, the emergence of “public interest” lobbying groups, increased concern for the rights of and provision of opportunities for minorities and women to participate in the polity and economy, and a pervasive criticism of those who possessed or were even thought to possess excessive power or wealth. The spirit of protest, the spirit of equality, the impulse to expose and correct inequities were abroad in the land. The themes of the 1960s were those of the Jacksonian Democracy and the muckraking Progressives; they embodied ideas and beliefs which were deep in the American tradition but which usually do not command the passionate intensity of commitment that they did in the 1960s. That decade bore testimony to the vitality of the democratic idea. It was a decade of democratic surge and of the reassertion of democratic egalitarianism . . .

The 1960s also saw, of course, a marked upswing in other forms of citizen participation, in the form of marches, demonstrations, protest movements, and “cause” organizations (such as Common Cause, Nader groups, and environmental groups). The expansion of participation throughout society was reflected in the markedly higher levels of self-consciousness on the part of blacks, Indians, Chicanos, white ethnic groups, students, and women—all of whom became mobilized and organized in new ways to achieve what they considered to be their appropriate share of the action and of the rewards . . . Previously passive or unorganized groups in the population now embarked on concerted efforts to establish their claims to opportunities, positions, rewards, and privileges, which they had not considered themselves entitled to before . . .

THE DECLINE IN GOVERNMENTAL AUTHORITY

. . . The essence of the democratic surge of the 1960s was a general challenge to existing systems of authority, public and private. In one form or another, this challenge manifested itself in the family, the university, business, public and private associations, politics, the governmental bureaucracy, and the military services. People no longer felt the same compulsion to obey those whom they had previously considered superior to themselves in age, rank, status, expertise, character, or talents . . . Authority based on hierarchy, expertise, and wealth all, obviously, ran counter to the democratic and egalitarian temper of the times, and during the 1960s, all three came under heavy attack.

CONCLUSIONS: TOWARDS A DEMOCRATIC BALANCE

. . . Al Smith once remarked that “the only cure for the evils of democracy is more democracy.” Our analysis suggests that applying that cure at the present time could well be adding fuel to the flames. Instead, some of the problems of governance in the United States today stem from an excess of democracy—an “excess of democracy” in much the same sense in which David Donald used the term to refer to the consequences of the Jacksonian revolution which helped to precipitate the Civil War. Needed, instead, is a greater degree of moderation in democracy.

“Attention Disorder or Not, Pills to Help in School,”

New York Times, Alan Schwarz, October 9, 2012

CANTON, GA.—When Dr. Michael Anderson hears about his low-income patients struggling in elementary school, he usually gives them a taste of some powerful medicine: Adderall.

The pills boost focus and impulse control in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Although A.D.H.D. is the diagnosis Dr. Anderson makes, he calls the disorder “made up” and “an excuse” to prescribe the pills to treat what he considers the children’s true ill—poor academic performance in inadequate schools.

“I don’t have a whole lot of choice,” said Dr. Anderson, a pediatrician for many poor families in Cherokee County, north of Atlanta. “We’ve decided as a society that it’s too expensive to modify the kid’s environment. So we have to modify the kid.”

Dr. Anderson is one of the more outspoken proponents of an idea that is gaining interest among some physicians. They are prescribing stimulants to struggling students in schools starved of extra money—not to treat A.D.H.D., necessarily, but to boost their academic performance.

It is not yet clear whether Dr. Anderson is representative of a widening trend. But some experts note that as wealthy students abuse stimulants to raise already-good grades in colleges and high schools, the medications are being used on low-income elementary school children with faltering grades and parents eager to see them succeed.

“We as a society have been unwilling to invest in very effective nonpharmaceutical interventions for these children and their families,” said Dr. Ramesh Raghavan, a child mental-health services researcher at Washington University in St. Louis and an expert in prescription drug use among low-income children. “We are effectively forcing local community psychiatrists to use the only tool at their disposal, which is psychotropic medications.”