PRINCIPLE #3

REDESIGN

THE ECONOMY

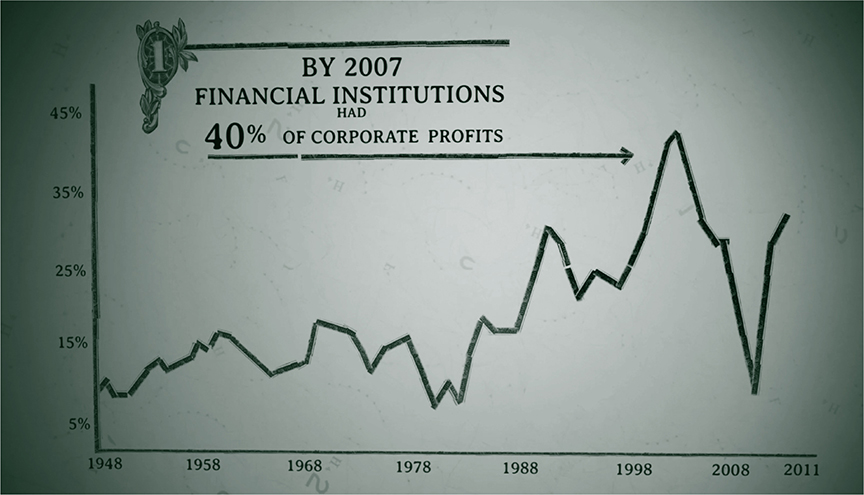

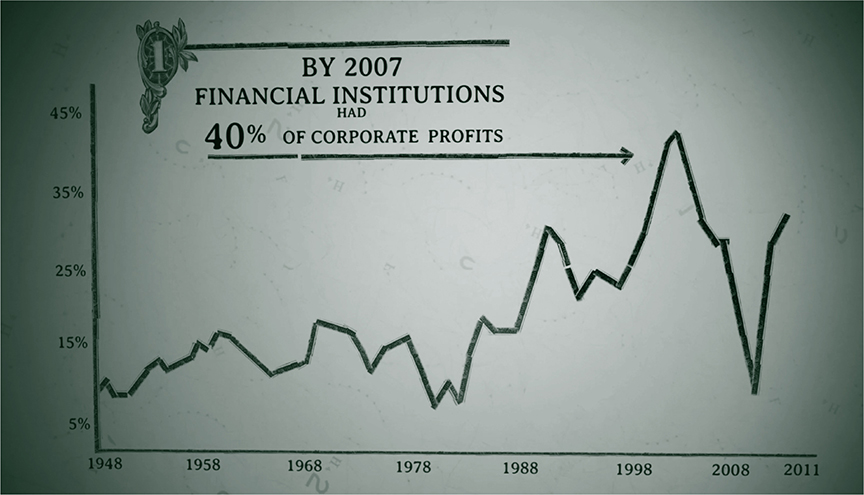

SINCE THE 1970s, there’s been a concerted effort on the part of the “masters of mankind,” the owners of the society, to shift the economy in two crucial respects. One, to increase the role of financial institutions: banks, investment firms, insurance companies, and so on. By 2007, right before the latest crash, they had literally 40 percent of corporate profits, far beyond anything in the past.

THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Back in the 1950s, as for many years before, the United States economy was based largely on production. The United States was the great manufacturing center of the world. Financial institutions used to be a relatively small part of the economy and their task was to distribute unused assets like bank savings to productive activity. That’s a contribution to the economy. A regulatory system was established. Banks were regulated. The commercial and investment banks were separated, and cut back their risky investment practices that could harm private people. There had been, remember, no financial crashes during the period of New Deal regulation. By the 1970s, that changed.

Up until the early 1970s there was an international economic system, established by the victors in World War II, the United States and Britain—Harry Dexter White for the United States, and John Maynard Keynes for Britain. It was called the Bretton Woods system, and based pretty much on regulation of capital, so currencies were regulated relative to the dollar, which was linked to gold. Now, there was very little currency speculation, because there’s no room for it. The International Monetary Fund was permitting, even supporting, government controls on the export of capital. The World Bank was financing state-run development projects. That was in the ’50s and ’60s, but by the 1970s that was dismantled. Completely dismantled. Controls on currencies were removed, which led predictably to an immediate sharp increase in speculation against currency.

FINANCIALIZATION

At the same time the rate of profit on industrial production was declining—there was still plenty of profit—but the rate was declining. So you started getting a huge increase in the flows of speculative capital—an astronomical increase—and enormous changes in the financial sector from traditional banks to risky investments, complex financial instruments, money manipulations, and so on.

Increasingly, the business of the country isn’t production, at least not here. You can even see it in the choice of directors. The head of a major American corporation back in the ’50s and ’60s was very likely to be an engineer, somebody who graduated from a place like MIT, maybe industrial management. There was a sense in the ownership and management class that they’d better attend to the nature of the society—that this was their workforce, this was their market, and they had to look forward to the future of their own corporation. That’s less and less true.

More recently, the directorship and the top managerial positions are people who came out of business schools, learned financial trickery of various kinds, and so on. And it’s changed the attitude of the corporation and of the leadership to the firm. There’s less loyalty to the firm and more loyalty to oneself. The way to get ahead now in a major firm is to show the good results in the next quarter. That’s not the long-term future of the firm—it’s what you can get out of the next quarter—and that also determines your salary and bonuses and so on. So if business practices can be designed to make short-term profits and you can make a ton of money and it crashes, you leave—and you’ve got the money and the golden parachute. That’s changed the nature of the way firms are treated very significantly.

By the 1980s, say, General Electric could make more profit playing games with money than it could by producing in the United States. You have to remember that General Electric is substantially a financial institution today. It makes half its profits just by moving money around in complicated ways. It’s very unclear that they’re doing anything that’s of value to the economy. So what happened was a sharp increase in the role of finance in the economy, and a corresponding decline in domestic production. That’s one phenomenon, what’s called “financialization” of the economy. Going along with that is the offshoring of production.

OFFSHORING

There’s been a conscious decision to hollow out the productive capacity of the country, by shifting production to places where there’s cheaper labor, no health and safety standards, no environmental conditions, etc.—Northern Mexico, China, Vietnam, and so on. Producers are still making plenty of money, but they’re producing elsewhere. This is all quite profitable for multinationals—especially their managers and executives and shareholders—but, of course, very harmful to the population. So Apple, one of the biggest corporations, will happily produce in a Taiwanese-owned torture chamber in China—that’s about what it amounts to. China is mainly an assembly plant. Foxconn, in Southwest China, can produce there with parts and components sent in from the surrounding industrial areas—Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, and the United States—with the profits coming primarily here, though there’s a class of millionaires or billionaires developing in China, too, a traditional third-world phenomenon.

In fact, what are called international “free trade agreements” are not free trade at all. The trade system was reconstructed with a very explicit design of putting working people in competition with one another all over the world. What it’s led to is a reduction in the share of income on the part of working people. It’s been striking in the United States, but it’s happening worldwide. It means that an American worker’s in competition with the super-exploited worker in China.

Incidentally, in China the inequality has grown enormously. China and the United States are two of the most extreme in this respect. There are plenty of labor struggles in China trying to overcome this, but it’s a very harsh regime. It’s hard to do, but something’s happening—and that’s global. What the United States is exporting are operative values—the concentration of wealth, tax on working people, deprivation of rights, exploitation, and so on—that’s what’s being exported in the real world. It’s kind of an automatic consequence of designing trade systems to protect the rich and privileged.

In the manufacturing sector in the United States, unemployment has recently been at the level of the Great Depression, but with a fundamental difference—those jobs aren’t coming back, at least not under current programs. Those manufacturing jobs are not going to come back unless social policy changes. Because those who run the society, the “masters of mankind”—to once again borrow Adam Smith’s phrase—they have different plans. They aren’t interested in having large-scale manufacturing come back to the United States, because they can make more profit by exploiting super-cheap labor with no environmental constraints elsewhere.

Meanwhile, highly paid professionals are protected. They’re not placed in competition with the rest of the world—far from it. And, of course, capital is free to move. Workers aren’t free to move, labor can’t move, but capital can. Again, going back to the classic authors like Adam Smith, as he pointed out, “free circulation of labor” is the foundation of any free trade system, but workers are pretty much stuck. The wealthy and the privileged are protected, so you get obvious consequences. And they’re recognized and, in fact, praised.

WORKER IN SECURITY

Policy is designed to increase insecurity. Alan Greenspan, when he testified to Congress, he explained his success in running the economy as based on what he called “greater worker insecurity.” Keep workers insecure, they’re going to be under control. They are not going to ask for decent wages or decent working conditions, or the opportunity of free association—meaning to unionize. If you can keep workers insecure, they’re not going to ask for too much. They’ll just be delighted—they won’t even care if they have to have rotten jobs, they won’t ask for decent wages, they won’t ask for decent working conditions, they won’t ask for benefits—and by some theory, that’s considered a healthy economy.

The way that people in the US have been able to maintain their lifestyles in the last thirty years of stagnation is, first of all, by higher working hours. American working hours are now way beyond Europe’s, benefits have declined, people are kind of getting by with debt. When you have growing worker insecurity, people go deeper and deeper into debt to try to keep going. Borrowing, buying worthless assets, inflated housing prices, all giving the illusion of wealth that you could use for consumption, for a nest egg for the future, education for your children—of course that can’t go on.

The US now has much higher working hours than comparable countries, and that has a disciplinary effect—less freedom, less time for leisure, less time for thought, more following orders, and so on—there are big effects of that. Now you see two adults in the family in the workforce, and families are collapsing because there are no public services as there are in comparable countries. If current social and economic tendencies continue, our grandchildren will increasingly be managers and executives sending jobs out to Southwest China—in these professional sectors there are going to be opportunities. But for the mass of the population it’s essentially service work—you work at McDonald’s.

Now, for the masters of mankind, that’s fine. They make their profits. But for the population, it’s devastating. These two processes, financialization and offshoring, are part of what leads to the vicious cycle of concentration of wealth and concentration of power. Producers are still making plenty of money, but they’re elsewhere. The major American corporations are getting most of their profit from abroad, and that creates all sorts of opportunities to shift the burden of sustaining the society onto the rest of the population.

THE COUNTER FORCE

Now, there have been efforts to restore some form of regulatory measures, like Dodd-Frank. But the business world has lobbied very hard to create exceptions, so that much of the shadow-banking system has been exempted from regulation by lobbyist pressure. And there’s gonna be constant pressure—we can be certain of it—from systems of power to prevent any constraint on expanding their power, and the profit. And the only counterforce is you. To the extent that the public fights back, effective systems can be created—not only to regulate the big banks, but to insist they demonstrate their legitimacy. And that challenge should be imposed on the institutions of the financial system, very broadly. That’s another task for an organized, committed, dedicated population—not just to regulate them, but to ask why they’re there.

Remember, it’s not a law of nature that the United States doesn’t have a manufacturing industry. Why should management make those decisions? Why shouldn’t those decisions be in the hands of what are called “stakeholders,” the workforce and the community? Why shouldn’t they decide what happens to the steel industry? Why shouldn’t they run the steel industry? These are very concrete questions. In fact, we’re constantly seeing cases where, if there were enough popular mobilization and activism, we would have a productive industry manufacturing the right things. I’ll mention one striking example.

After the housing bubble and the financial crash, as you remember, the government pretty much took over the auto industry. It was virtually nationalized and in government hands. That means popular hands. That meant there were choices that the public could’ve made. If there had been an organized, active public, there would have been choices that people like us could’ve made about what to do with the auto industry. Well, unfortunately, there wasn’t that active mobilization and organization, so what was done was the natural thing that benefits the powerful. The industry was pretty much a taxpayer expense, and returned to essentially the same owners—some different faces, but the same banks, the same institutions, and so on—and it went on producing what it had been producing: automobiles.

There was another possibility. The industry could have been handed over to the workforce and the communities, and they could have made a democratic decision about what to do. And maybe their decision—I would at least hope that their decision—would have been to produce what the country desperately needs, which is not more cars on the street, but efficient mass transportation for our own benefit, and for the benefit of our grandchildren. If they’re gonna have a world to survive in, it’s not gonna be through automobiles—it’s gonna be through efficient forms of transportation. Retooling it wouldn’t have been that expensive, and it would be beneficial to them, beneficial to us, beneficial to the future. That was a possibility. And things like that are happening all the time, constantly.

This is one of the few countries, certainly one of the few developed societies, that doesn’t have high-speed transportation. You can take a high-speed train from Beijing to Kazakhstan, but not from New York to Boston. In Boston, where I live, many people literally spend three or four hours a day just commuting. That’s crazy wasted time. All of this could be overcome by a rational mass transportation system, which would also contribute significantly to solving the major problem we face—namely, environmental destruction. So that’s one kind of thing that could be done, but there are many others, large and small.

So, there’s no reason why production in the United States can’t be for the benefit of people, of the workforce in the United States, the consumers in the United States, and the future of the world. It can be done.

“AN END TO THE

FOCUS ON SHORT TERM URGED,”

2009, and other sources

“An End to the Focus on Short Term Urged,”

Wall Street Journal, Justin Lahart, September 9, 2009

Investors’, corporate boards’ and managers’ focus on short-term gain has become so detrimental to the economy that unless they voluntarily change their behavior, regulators should step in, according to an Aspen Institute statement to be released Wednesday that is signed by Berkshire Hathaway Chief Executive Officer Warren Buffett, Vanguard Group founder John Bogle and former International Business Machines CEO Louis Gerstner, among others.

“We believe that short-term objectives have eroded faith in corporations continuing to be the foundation of the American free enterprise system, which has been, in turn, the foundation of our economy,” said the statement, signed by 28 high-profile managers, investors, academics and others.

Over the past several decades, investors have become increasingly focused on the short term, trading more and more frequently. In 1990, for example, the average holding period of a stock trading on the New York Stock Exchange was 26 months; now it’s less than nine months. At the same time, companies have become more focused on the short term as well, with managers concentrating on hitting near-term targets, such as analysts’ quarterly earnings estimates, and as a result often forgoing measures that promote long-term growth, such as research and development—or even routine maintenance.

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the

Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith, 1776

[The] policy of Europe, by not leaving things at perfect liberty, occasions other inequalities of much greater importance.

It does this chiefly in the three following ways. First, by restraining the competition in some employments to a smaller number than would otherwise be disposed to enter into them; secondly, by increasing it in others beyond what it naturally would be; and, thirdly, by obstructing the free circulation of labour and stock, both from employment to employment and from place to place . . .

Thirdly, the policy of Europe . . . occasions in some cases a very inconvenient inequality in the whole of the advantages and disadvantages of their different employments.

The Statute of Apprenticeship obstructs the free circulation of labour from one employment to another, even in the same place. The exclusive privileges of corporations obstruct it from one place to another, even in the same employment . . .

Whatever obstructs the free circulation of labour from one employment to another obstructs that of stock likewise; the quantity of stock which can be employed in any branch of business depending very much upon that of the labour which can be employed in it. Corporation laws, however, give less obstruction to the free circulation of stock from one place to another than to that of labour. It is everywhere much easier for a wealthy merchant to obtain the privilege of trading in a town corporate, than for a poor artificer to obtain that of working in it.

The obstruction which corporation laws give to the free circulation of labour is common, I believe, to every part of Europe. That which is given to it by the Poor Laws is, so far as I know, peculiar to England. It consists in the difficulty which a poor man finds in obtaining a settlement, or even in being allowed to exercise his industry in any parish but that to which he belongs. It is the labour of artificers and manufacturers only of which the free circulation is obstructed by corporation laws. The difficulty of obtaining settlements obstructs even that of common labour. It may be worth while to give some account of the rise, progress, and present state of this disorder, the greatest perhaps of any in the police of England.

Testimony of Chairman Alan Greenspan before the

US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and

Urban Affairs, February 26, 1997

[An] acceleration in nominal labor compensation, especially its wage component, became evident over the past year. But the rate of pay increase still was markedly less than historical relationships with labor market conditions would have predicted. [A]typical restraint on compensation increases has been evident for a few years now and appears to be mainly the consequence of greater worker insecurity. In 1991, at the bottom of the recession, a survey of workers at large firms by International Survey Research Corporation indicated that 25 percent feared being laid off. In 1996 . . . the same survey organization found that 46 percent were fearful of a job layoff.

The reluctance of workers to leave their jobs to seek other employment as the labor market tightened has provided further evidence of such concern, as has the tendency toward longer labor union contracts. For many decades, contracts rarely exceeded three years. Today, one can point to five-and six-year contracts—contracts that are commonly characterized by an emphasis on job security and that involve only modest wage increases. The low level of work stoppages of recent years also attests to concern about job security.

Thus, the willingness of workers in recent years to trade off smaller increases in wages for greater job security seems to be reasonably well documented.