PRINCIPLE #5

ATTACK SOLIDARITY

SOLIDARITY IS quite dangerous. From the point of view of the masters, you’re only supposed to care about yourself, not about other people. This is quite different from the people they claim are their heroes, like Adam Smith, who based his whole approach to the economy on the principle that sympathy is a fundamental human trait—but that has to be driven out of people’s heads. You’ve got to be for yourself and follow the vile maxim—“don’t care about others”—which is okay for the rich and powerful, but devastating for everyone else. It’s taken a lot of effort to drive these basic human emotions out of people’s heads.

We see it today in policy formation—for example, in the attack on Social Security. There’s a lot of talk about the crisis of Social Security, which is nonexistent. It’s in quite good shape—about as good as it’s ever been. Social Security is a very effective program, and has almost no administrative cost. To the extent that there’s a potential crisis a couple of decades from now, there’s an easy way to fix it. But policy debate concentrates on it, to a large extent, because the masters don’t want it—they’ve always hated it, because it benefits the general public. But, actually, there’s another reason for hating it.

Social Security is based on a principle. It’s based on a principle of solidarity. Solidarity: caring for others. Social Security means, “I pay payroll taxes so that the widow across town can get something to live on.” For much of the population, that’s what they survive on. It’s of no use to the very rich so, therefore, there’s a concerted attempt to destroy it. One of the ways is by defunding it. You want to destroy some system? First defund it. Then, it won’t work. People will be angry, and they’ll want something else. It’s a standard technique for privatizing some system.

THE ATTACK ON PUBLIC EDUCATION

We see it in the attack on public schools. Public schools are based on the principle of solidarity. I no longer have children in school. They’re grown up, but the principle of solidarity says, “I happily pay taxes so that the kid across the street can go to school.” Now, that’s normal human emotion. You have to drive that out of people’s heads. “I don’t have kids in school. Why should I pay taxes? Privatize it,” and so on. The public education system—all the way from kindergarten to higher education—is under severe attack. That’s one of the jewels of American society.

You go back to the Golden Age again, the great growth period in the ’50s and ’60s. A lot of that is based on free public education. One of the results of the Second World War was the GI Bill of Rights, which enabled veterans—and remember, that’s a large part of the population then—to go to college. They wouldn’t have been able to, otherwise. They essentially got free education. I went to college in 1945—I wasn’t a veteran, I was too young, but it was virtually free. It was an Ivy League school, the University of Pennsylvania, but the tuition was one hundred dollars and you could easily get a scholarship.

I should mention that if you looked at the faces of the people who were coming out of the colleges during the period, they were all white. The GI Bill and many other social programs were actually designed on racist principles that are deeply embedded in our history, and have by no means been overcome. Nevertheless, with that aside, from the nineteenth century the US was way in the lead in developing extensive mass public education at every level.

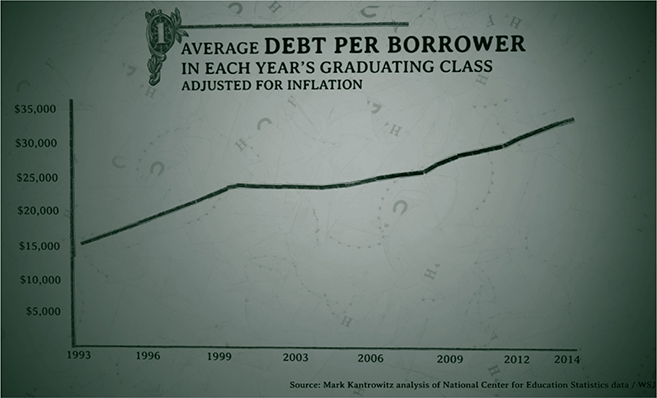

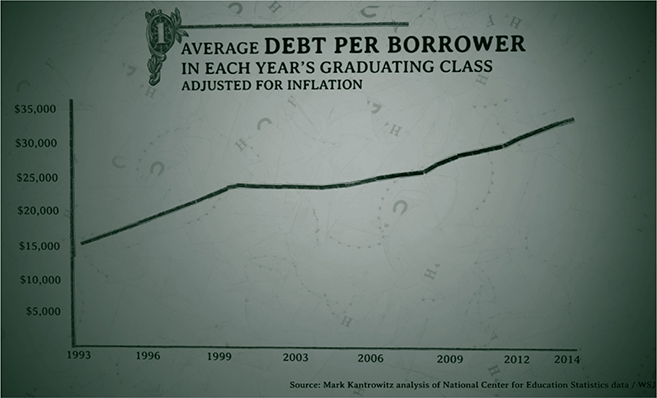

By now, however, in more than half the states, most of the funding for the state colleges comes from tuition, not from the state. That’s a radical change, and that’s a terrible burden on students. It means that students, if they don’t come from very wealthy families, they’re going to leave college with big debts. And if you have a big debt, you’re trapped. I mean, maybe you wanted to become a public interest lawyer, but you’re going to have to go into a corporate law firm to pay off those debts. And by the time you’re part of the culture, you’re not going to get out of it again. That’s true across the board.

In the 1950s, it was a much poorer society than it is today but, nevertheless, it could easily handle essentially free mass higher education. Today, a much richer society claims it doesn’t have the resources for it. That’s just what’s going on right before our eyes. That’s the general attack on principles that—not only are they humane—are the basis of the prosperity and health of this society.

PRIVATIZATION

And that’s constant. Take, say, some of the proposals for Medicare—basically destroying Medicare and privatizing it. They are carefully designed so that at the beginning it exempts people over fifty-five, a substantial part of the voting population. If you want to get it through the legislatures, you better get the voters. So there’s a hope that the elderly will be so vicious that they’re willing to punish their children and their grandchildren so that they can get decent health care. That’s what the principle is based on.

And, of course, as their children grow older and grandchildren come into it, they’ll be subject to the sharp cuts in medical aid that come from the design of these programs. It’s designed on the “sunset principle” so that the main sector of voters will be willing to go along with it. And when the legislation’s passed, then the rest—including their children and grandchildren—they’ll be the ones stuck with the trillions of dollars in costs to get medical care.

We have the only health care system in the advanced world that is based overwhelmingly on virtually unregulated private health care, and that is extremely inefficient and very costly. All sorts of administrative costs, bureaucracies, surveillance, simple billing—things that just don’t exist in rational health care systems. And I’m not talking about anything utopian—almost every other industrial society has them and, in fact, they are far more efficient both in outcomes and costs than the one we have in the United States. That’s a scandal, but also quite apart from the millions of people who have no insurance at all, and are even more insecure.

I should say it’s not just the insurance companies and financial institutions that are driving this but also the pharmaceutical corporations. The United States, I think, is the only country in the world in which the government, by law, is not permitted to negotiate drug prices. So the Pentagon can negotiate prices for pencils, but the government can’t negotiate drug prices for Medicare and Medicaid. Actually, there’s one exception to that, the Veterans Administration. They’re allowed to negotiate drug prices so that they’re far lower. They’re at world standards. But legislation has been introduced to prevent people from benefiting from the lower prices elsewhere, of course radically in violation of free trade. The rhetoric is free trade but certainly not the policies.

In fact, the Veterans Administration is far more efficient, the drug costs are much lower, the general costs are much lower, and outcomes are better. The Medicare system itself in the United States is quite efficient, as well—administrative costs for Medicare are far below those of private insurance. And remember, these are both government health programs. Medicare costs are skyrocketing now, only because they have to work through the privatized, unregulated insurance system. It’s known how to deal with these questions; in fact, we have models all around us. But you can’t touch them because they’re too powerful in the economy. It’s kind of interesting to see what happens in the rare case when it is brought up. In the New York Times, occasionally it’s been called “politically impossible” or “lacking political support” when, actually, a majority of the population has wanted it for a long time.

When Obama instituted the Affordable Care Act, as you may recall, there was originally talk about a public option, which means national health care. It was supported by almost two-thirds of the population. But it was dropped—no discussion. You go back even earlier to the late Reagan years, and about 70 percent of the population thought that national health care ought to be a constitutionally guaranteed right. In fact, about 40 percent of the population thought it already was a constitutionally guaranteed right. But that’s not political support—political support means Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, and so on—that’s political support. In fact, if we had a health care system like other countries, we would have no deficit, we’d probably have a surplus.

ELIMINATING GOVERNMENT

It’s very striking to see the debate in the United States—also in Europe, incidentally—about the current economic problems. The major human problem, overwhelmingly, isn’t the deficit—it’s joblessness. Joblessness has a devastating effect on a society. I mean, there are terrible consequences for the people and their families. But it also has a terrible economic effect—it’s pretty obvious why; when people aren’t working there are resources that could develop the economy that are not being used—they’re being wasted.

It sounds like an inhuman way to talk about it—the human cost is the worst part. But from a straight economic point of view, it’s as if you somehow decided to leave factories idle. Take a trip to Europe, Japan, or even China, and then come back to the United States. One of the things that immediately strikes you is the country’s falling apart, you often feel like you’re returning to a third world country. Infrastructure has collapsed, health care is a total wreck, the educational system is being torn to shreds, nothing works, and with incredible resources. To get people to sit passively and look at that reality takes very effective propaganda. That’s essentially what’s happening—you have a big workforce that’s eager to work, highly skilled, with lots of things that have to be done. The country needs all sorts of things.

Financial institutions don’t like the idea of a deficit, and they also don’t want that much of a government. This has been taken to the extreme by people like Grover Norquist, who’s very influential. He has this pledge that all Republicans have to sign—and they do—which is that you’re not allowed to increase taxes, that you must reduce the government. As he puts it, he wants to basically eliminate the government. Well, from the point of view of the masters, that’s kind of understandable. The government does, to the extent that democracy functions, carry out actions in the interests of and determined by the population. That’s what democracy means. And they, of course, would prefer to have total control without interference of the public. So they’re happy to see the government diminished—with two caveats that have to be added. They want to make sure that there’s a powerful state there that can mobilize taxpayers to bail them out and to enrich them further. And, secondly, they want a major military force to make sure that the world is under control.

That’s what they want the state to be restricted to—nothing like making sure elderly people get medical care or a disabled widow gets enough to live on. That’s not their business, it’s not in accord with the vile maxim, so they’re concentrating on the deficit. For the public, joblessness is of far greater importance. But, with few exceptions, like Paul Krugman, the public discussion remains focused on the deficit.

Overwhelmingly, the discussion is shaped by the masters: “look at the deficit, forget everything else.” But even when looking at the deficit, it’s very striking that they omit anything about the causes of the deficit. The causes of the deficit are pretty clear. One is the extraordinary military spending that’s about the same as that of the rest of the world combined. Not for security, incidentally (that’s another story)—it doesn’t provide security except for the masters that control the world and their interests. And that’s almost untouchable.

A RETURN TO SOLIDARITY

How do we make higher education more affordable? Very easy—by doing it.

Take a look at the world, at ourselves, and we see very simple answers to this. Finland comes out close to the top on virtually any measure of educational achievement—how much do you pay to go to college? Nothing. It’s free. Take Germany, another rich country with a pretty successful educational system—how much do you pay? Essentially nothing. Take a poor country right near us—Mexico happens to have a pretty good higher educational system, I’ve been impressed with what I’ve seen. Salaries are very low because it’s a very poor country, but how much do you pay? Nothing.

There is no economic reason why education can’t be available to everyone for free—there are social and political reasons. But those are social and political decisions. In fact, the economy would almost certainly be better off if more people did have the opportunity to develop themselves and contribute to society through what higher education can offer.

THE THEORY OF MORAL SENTIMENTS,

1759, and other sources

The Theory of Moral Sentiments,

Adam Smith, 1759

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion which we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrow of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all the other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to the virtuous and humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

Social Security Act of 1935

An act to provide for the general welfare by establishing a system of Federal old-age benefits, and by enabling the several States to make more adequate provision for aged persons, blind persons, dependent and crippled children, maternal and child welfare, public health, and the administration of their unemployment compensation laws; to establish a Social Security Board; to raise revenue; and for other purposes.

Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944

As used in this part, the term educational or training institutions shall include all public or private elementary, secondary, and other schools furnishing education for adults, business schools and colleges, scientific and technical institutions, colleges, vocational schools, junior colleges, teachers colleges, normal schools, professional schools, universities, and other educational institutions, and shall also include business or other establishments providing apprentice or other training on the job, including those under the supervision of an approved college or university or any State department of education, or any State apprenticeship agency or State board of vocational education, or any State apprenticeship council or the Federal Apprentice Training Service established in accordance with Public, Numbered 308, Seventy-fifth Congress, or any agency in the executive branch of the Federal Government authorized under other laws to supervise such training.