Were it not that Rod’s mood was too good for Troy to want to ruin it, it occurred to him that a way to smash through the irritating smugness of his good-feeling might be to show him, in his professional capacity as a member of his majesty’s government, the interior of a London pawnshop. It was one way to read the economic health of the nation. After all, he thought, one might readily understand the circumstances that might lead a man to pawn his best winter overcoat (display three: two black, one blue) or the wife’s fox fur stole (display five: all a bit the worse for wear) or the sailor to pawn his concertina (display nine), but what in the economic downturn that seemed to be the permanent condition of the nation could be quite so bad as to compel a man to pawn his winter underwear (display: eleven pairs of long johns, condition variable)—and at that, to do so and not to have acquired the wherewithal to redeem them by November?

Gazing at the motley, Troy saw high on the shelf above the door to the back room a dusty viola without strings and he knew at last why she had given him the ticket and what it was for.

An unshaven grump in a grubby shirt and grubbier waistcoat took the ticket from him, peered at it, and said, “Good job I’m not a betting man. I ’ad ’er down as a no-show. Didn’t think I’d see ’er again. But . . . I suppose I ’aven’t cos you’re here instead, ain’t you? I told her last week there weren’t no call for ’em any more. But I took it all the same. Do you know, she wanted fifty quid for it? Fifty quid! Would you Adam an’ Eve it? But I told ’er straight, there ain’t no call for ’em and she could count herself lucky I was offerin’ a tenner for it.”

“A tenner?” said Troy, incredulous.

“Well, I know it’s an old un but the case is new. Gotta be worth summink init?”

Troy put down two five-pound notes and counted out the interest in silver.

“I’ll take it now,” he said.

“In the back. Such a big bugger I couldn’t leave it lyin’ around the shop.”

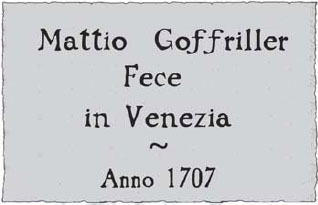

In the back, surrounded by a cornucopia of filth, Troy opened the case and took one of the tools of his trade from his inside pocket—a small Ever Ready torch in the shape of a fountain pen. He shone the narrow beam though an ƒ-hole onto the label:

“Wossat?”

“The maker’s label. Mattio Goffriler made cellos in the eighteenth century, in Italy.”

“Worth summink, is it?”

And while tact and courtesy were clearly options, they were on a hiding to nothing when up against the sheer pleasure in annoyance that the truth would cause. Troy did not feel like sparing the feelings or the wallet of a grumpy old man who gave out coppers for long johns and who had given Voytek ten pounds for the most precious object in her life.

“Well,” he said, “the last time a Mattio Goffriler cello came up at Sotheby’s it fetched almost five thousand pounds.”