CHAPTER ONE

Introduction to the Debt Market

What defines the debt market is that in each transaction there is an entity that borrows money (the issuer) and a lender(s) who loans it (investors). The amount of money the lender(s) provide the borrower is called the principal. The borrower uses the money it borrows to buy assets, grow a business, pay its bills, and so forth. Usually, the borrower pays the lender interest (a percentage of the money borrowed) periodically for the use of the money. The rate of interest and the interest payment schedule are determined by negotiation between the borrower and the lenders. When a loan matures (comes due), the borrower returns the principal and any remaining unpaid interest to the lender.

The global debt market (measured as if all debt was first converted to US$) is greater than $200 trillion, which dwarfs the size of the global equity (stock) market. From a purely economic point of view, the debt market is far more important than the equity market.

SEGMENTATION BASED ON MATURITY

The debt market is divided into three segments based upon the time until the loan matures:

- The money market includes loans that mature in 1 year or less.

- The note market includes loans that mature in 1–10 years.

- The bond market includes loans that mature in more than 10 years.

Investors refer to these as 7-year US Treasury note, the 5-year US Treasury note, and the 20-year Treasury bond.

INTEREST PAYMENT FREQUENCY

The frequency of interest payments varies depending upon the type of loan vehicle:

- Daily—money market funds

- Monthly—mortgages

- Quarterly—interest rate swaps

- Semiannual—US notes and bonds

- Annual—euro notes and bonds

THE COUPON

The interest rate (aka the coupon) on the loan can be:

- Fixed for the life of the loan. If the principal is $1,000 and the coupon is 6%, the borrower will pay the investor $60 a year until the principal is repaid. (Note that the interest is always calculated on the face value or principal value of the loan—not the loan’s resale value in the secondary market.) Some of the many factors that determine the interest rate on a fixed rate loan include:

- The current level of interest rates in the market

- The length of the loan—usually the longer the loan, the higher the rate

- The credit quality of the borrower

- The promises the lender makes the investors in exchange for receiving the loan, called covenants. Each covenant is designed to protect the investor’s interests. Some examples of these include limitations on:

- Adding additional debt

- Selling or disposing of collateral

- Changing the company’s corporate structure

- Making dividend payments to shareholders or executing stock buyback programs

- Moving the company to a new country or state

- Making significant acquisitions

- Tied to an interest rate and allowed to float with that rate. The most commonly used index rates in the US are listed in Figure 1.1.

Common Floating Rate Indices

|

Name |

Definition |

|

T-bill |

The rate at which the US government can borrow money for the short term |

|

LIBOR |

The rate at which money center banks lend each other money |

|

COFI |

The bank’s average cost of funding itself |

|

Prime |

The rate the bank charges its best customers to borrow money |

Many investors consider the floating rate note (FRN) market to be boring and homogenous. Nothing could be further from the truth. Consider the below situation. XYZ Inc., an industrial firm, has issued two different FRNs with the coupons listed in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2

Alternative XYZ FRNs Before Crash

|

Name |

Index Rate |

Spread |

Yield |

|

$6M T-bill |

3% |

3% |

6% |

|

$6M LIBOR |

4% |

2% |

6% |

Both notes have equal credit quality, liquidity, and payment dates. As both notes currently yield 6%, how should an investor decide which to buy? The T-bill rate is the rate at which the US government can borrow money, while the LIBOR (London Interbank Offering Rate) is the rate at which large money center banks around the world can borrow US dollars. Because banks have more risk than the US government, the LIBOR rate is higher than the T-bill rate. The spread between them is a credit spread—currently 1%—that varies over time. For example, in 2007 there was a flight to quality as it appeared that many banks would collapse. The T-bill rate went to 0, while LIBOR rose to 6%—widening the T-bill/LIBOR spread to 6%. With the spread at 6%, the two notes had the yields listed in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3

Alternative XYZ FRNs During Crash

|

Name |

Index Rate |

Spread |

Yield |

|

$6M T-bills |

0% |

3% |

3% |

|

$6M LIBOR |

6% |

2% |

8% |

An investor clearly would have been better off buying the note tied to LIBOR and having the yield go from 6% to 8% instead of the T-bill-linked note that went from 6% to 3%. Naturally, after the yield change, the LIBOR note would trade at a premium and the T-bill note would trade at a discount.

The second issue with FRNs is how the formula is quoted. Look at the example shown in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4

Alternative XYZ FRNs During Crash

|

Name |

Index Rate |

Spread |

Yield |

|

$6M T-bill |

4% |

Add 1% |

5% |

|

$6M T-bill |

4% |

125% of Index |

5% |

The notes are identical with the exception of how the spread is defined. While both notes have an equal return now, the first note will outperform if rates decline, while the second will outperform if rates rise. Even though these are both FRNs, the irony is that investors still need to have an outlook on rates in order in order make the right choice:

- Zero coupon bonds (ZCBs). A ZCB doesn’t make periodic interest payments. Instead, the bond is sold at a discount and the payments are compounded internally until the bond matures and it pays its par value to the investor.

- Bonds tied to the price of a commodity or economic indicator. For example the interest you get paid might equal the:

- Rate of inflation + 1%

- Percentage increase in the price of oil on the NYMEX over a set time period

- Difference between the change in the value of the pound and the change in the value of the euro.

MATURITY OF DEBT

The maturity of the loan can be:

- Fixed (aka a Bullet Loan)—Neither the issuer nor the investor can alter the life of the loan.

- Extendable—The loan has a scheduled maturity date; however, the borrower can elect to extend the term of the loan, usually by paying a previously agreed upon higher interest rate. For example, a typical extendable loan might start as a 10-year 5% loan. If the borrower extends the maturity by 1 year, the rate in year 11 rises to 6%. If the borrower further extends the maturity by an additional year, the rate in year 12 rises to 7%. Finally, the borrower may extend the maturity a third year, but the rate changes to 8%. After 13 years, the loan is absolutely due. If the principal isn’t repaid, the loan is in default.

Extendable loans are most commonly used in the commercial real estate market. For example, a real estate investor buys a building for $10.5MM by putting up $500K and borrowing $10MM for 10 years at 5% with an interest-only mortgage. The investor hopes that the value of the building will rise over the next 10 years, so it can be sold at a profit. If it is sold at a profit, the investor then pays off the mortgage and banks the profit. But suppose in 10 years, the building is only worth $9.7MM. The building can either be sold at a loss— (the investor can put up another $300K to get out of the deal), or the investor can extend the financing. Since the building is worth less than the mortgage, the property can’t be refinanced. Instead, the existing loan must be extended for 1–3 years. Hopefully, for the investor, the value of the property will rise to more than $10MM over the next 1–3 years so the investor can refinance.

- Subject to a Put Option—If the loan is subject to a put option, the investor has the right to shorten the life of the loan, usually without paying a penalty. The investor can use the put to force the issuer to repurchase the bond at par—regardless of its current market value. The borrower will exercise the option if interest rates rise (so the investor can reinvest the principal at a higher rate) or if the issuer’s credit quality declines. Put options have three variables:

- Period of Put Protection—This is the period of time that passes between when the note is issued before the put option is activated or “knocked-in.” For example, a 10-year note might have 3 years of put protection meaning that the put option is only activated 3 years after the note was issued. A 20-year bond might have 5 years of “put protection.”

- Life of the Option—Once the option is knocked-in, three things can happen:

- The option can stay activated for the remaining life of the note. In this case the investor can put the bond any business day.

- The option can stay active for a brief period (a week or a month) and then turn off. This is a “use it or lose it” option. If the investor does not use the put during this period, the option is lost. If a 10-year note has a 3-year use it or lose it option, and the option is not used, the investor is left with 7-year bullet paper.

- The option can turn on and off, and then turn on again later on. For example, the 10-year note may become putable on its 3-year, 5-year and 7-year anniversary.

- Hard or Soft Put—A put can be “hard” or “soft.” If the put is “soft” the put can only be activated if some additional condition is met beyond passing the period of put protection. For example, one or more of the following conditions may have to be true in order for the put option to be activated:

- The credit quality of the issuer is downgraded.

- Management changes.

- The bond’s secondary market value drops below some pre-specified value.

- Subject to a Call Option—A note/bond can also have an embedded call option. If the loan is callable, the issuer has the right to shorten the loan. The issuer will exercise (use) this option when rates have declined so that the issuer can stop paying a high interest rate and reissue debt at a lower interest rate. Embedded call options have the same three variables as put options, namely:

- A period of call protection.

- Three alternatives once the option is activated.

- The option can be hard or soft.

However, unlike puts, call options also have an additional variable—the call premium. When the issuer calls a bond, the reason is that interest rates have declined since the bond was issued and it can issue new bonds at a lower rate. For example, a company might issue a 10% 20-year bond that is callable in 5 years. If, in 5 years, interest rates are at 6%, the issuer will no longer want to pay 10% and so will call in the 10% bond issue. The investor will then receive their money back and have to reinvest it at a lower rate. Because calls always hurt investors, most issuers try to partially offset the pain by calling the bond at a premium to par. This premium price is still less than the bond’s true value—but at least it is a gesture of goodwill. A typical premium schedule for a 20-year bond with 5 years of call projection would be:

- $1,040 if the bond is called in year 6.

- $1,030 if the bond is called in year 7.

- $1,020 if the bond is called in year 8.

- $1,010 if the bond is called in year 9.

- $1,000 if the bond is called in year 10 or later.

Note: It costs money to call in a bond and issue new ones and so the interest savings must at least cover the costs. Therefore, if the company is paying 10% and interest rates for new bonds drop to 9.97%, the issuer will not call in its 10% bonds.

- Subject to a Sinking Fund—If a bond is subject to a sinking fund, the issuer is required to periodically pay off a portion of the principal instead of paying it off all at once at maturity. For example, suppose a company issues $100MM of 8% 10-year notes to raise the money to build a new factory. The notes, however, are subject to the sinking fund in Figure 1.5.

FIGURE 1.5

Cash Flow Schedule for a Sinking Bond

From an operational perspective, prior to the annual anniversary of the issue, the issuer can either:

- Buy back the required number of bonds in the open market if the bonds are trading below par in the secondary market. After it buys them back, it cancels them.

- Call in the bonds (usually by random draw) if the bonds are trading above par in the secondary market.

A well-designed sinking fund benefits both the issuer and investors. Looking at the schedule shown in Figure 1.5, in years 1 and 2, the plant is being built and debugged, and so it is not generating any cash. The borrower is only paying the interest to keep its cash flow requirements to a minimum. By year 3, however, the plant should be running flat out and generating a profit. The issuer can use that profit to pay down some of its debt and therefore lower its future interest expense.

From the investor’s point of view, as the plant generates profits, using those profits to pay down the principal reduces the investor’s credit risk. At the end of year 10, the borrower only needs to pay off or refinance $57.5MM instead of $100MM. Even though the plant is now 10 years old, it should still be worth at least $57.5MM.

A targeted redemption note (TARN) is a floating rate note that matures when the investor receives a certain amount of interest. If the total interest amount is 20%, the note will mature in 2 years if interest rates average 10%. The note will mature in 4 years if interest rates average 5%.

CREDIT RATING

Credit risk is the risk that the loan either won’t be repaid in full or will be repaid late. Naturally, different loans have different levels of credit risk. Some loans have virtually no risk, such as a short-term loans to the US government. Other loans have a high degree of risk, such as loans to start-up mining operations or biotech companies that haven’t yet perfected their products. High-risk loans naturally pay higher interest rates.

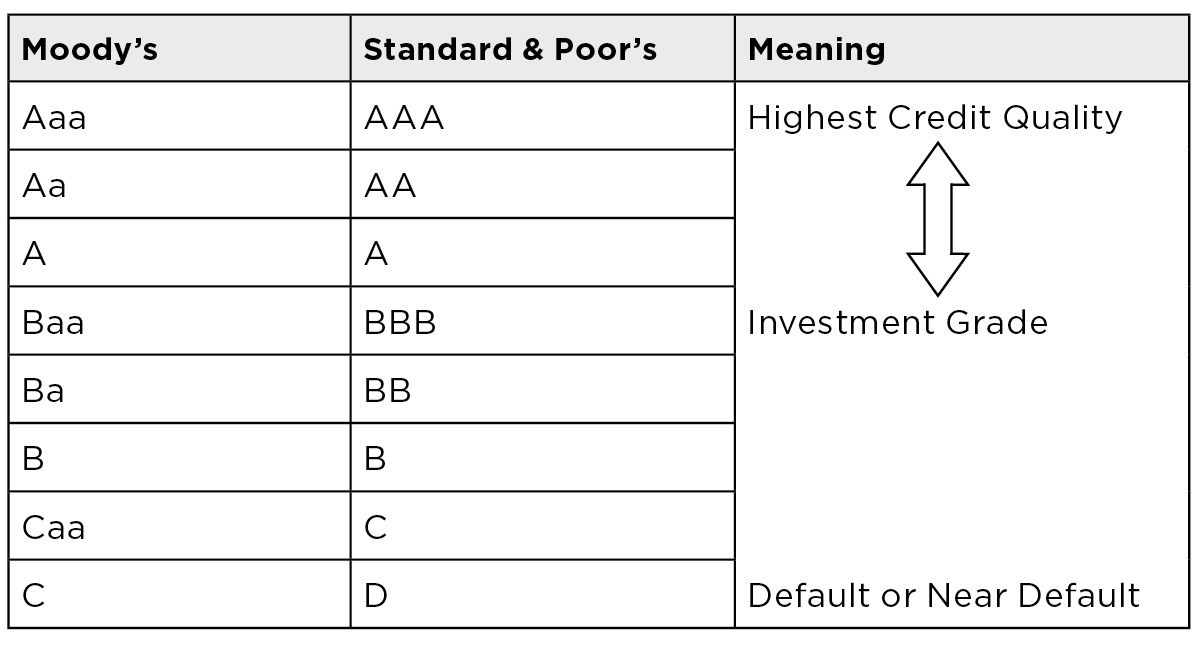

Because most investors lack the expertise to assess the level of credit risk in a particular loan, there are companies, such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, that offer professional credit analysis services. They assign loans ratings based on the probability that the loans will be repaid in full and on time. The ratings range from Aaa/AAA for a bond that has virtually no credit risk down to C or D for bonds that are already in default or where default is a high probability. The table shown in Figure 1.6 explains the major ratings.

FIGURE 1.6

Ratings from Major Rating Agencies

CAPITAL STRUCTURE

When corporations issue more than one bond, the relative seniority of each bond becomes a major issue. The seniority of the company’s various debt issues is referred to as the company’s capital structure. A typical capital structure is as follows:

- Senior debt with no recourse

- Secured debt with recourse

- Bank loans

- Derivative obligations

- Senior unsecured debt

- Trade obligations

- Senior subordinated debt

- Subordinated debt

- Convertible debt

- Income bond

- Preferred stock

- Common stock

Senior Debt with No Recourse

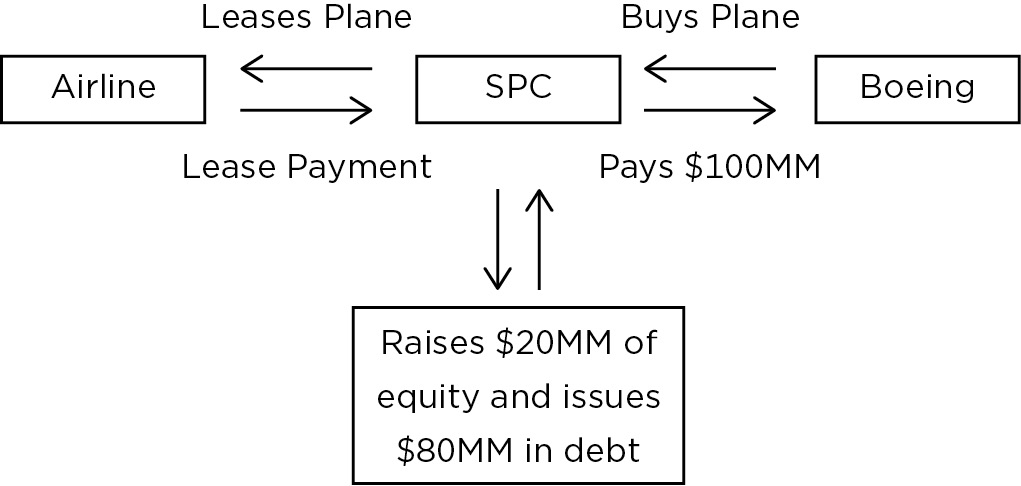

Senior debt with no recourse is secured debt that is not on the company’s balance sheet. A typical example would be as follows: A Ba rated US airline wants to borrow $100MM to buy a new aircraft. If the company borrows the money directly, it will have to pay a very high rate of interest because of its low credit rating. Instead, the company creates an independent special purpose corporation (SPC). The SPC is a completely separate entity that raises $20MM in equity plus $80MM in debt for a total of $100MM in capital. Because this debt is fully collateralized by the airplane and has $20MM of equity underneath it, it is priced like Aa rated debt.

The SPC uses its $100MM to buy the plane and then leases the plane to the airline. The airline only pays a monthly lease fee, as shown in Figure 1.7.

FIGURE 1.7

Typical Off Balance Sheet Financing Structure

In the event the airline files for bankruptcy, the airline can either:

- Maintain the lease payments, which it probably would do since its newest planes are the most comfortable and fuel efficient.

- Cancel the lease, in which case the SPC can lease the plane to another airline or resell the plane outright.

Since neither the plane nor the SPC is owned by the airline, the bankruptcy court has no jurisdiction over the SPC, its property, or its investors. This is what is meant by “no recourse.”

Secured Debt with Recourse

An alternative way for the airline to lower its financing costs is to issue the debt directly—but then secure the debt with segregated collateral. For example, the airline could buy the plane directly in its own name, and then put collateral (such as the title to the aircraft) into a trust account that was earmarked to serve as collateral just for this debt issue. Only after all the debt was paid off would any remaining value be available to other creditors. As long as the value of the plane exceeds the size of the debt, the debt is fully collateralized. Thus, the debt needs to be paid down at a faster rate than the airplane depreciates. In the event the company goes bankrupt, the investors will have to go through the bankruptcy process to pursue their claim.

Bank Loans

The first level of unsecured debt is bank lines of credit. Most companies maintain lines of credit that they can draw against to meet short-term cash shortfalls. These lines of credit are usually the most senior unsecured debt on the balance sheet. The term unsecured means that no collateral is specifically escrowed or segregated to back the debt. However, just because the debt doesn’t have segregated assets backing it, doesn’t mean the company doesn’t have sufficient assets to secure the debt. The company may have assets whose value is thousands of times greater than the company’s debts, but the assets are not specifically segregated to guarantee the debt.

Derivative Obligations

If the company has entered into any derivative contracts, such as interest rate swaps, cross currency swaps, and the like, these obligations are usually very senior. They must be paid before interest is paid to any debt that does not have specific collateral escrowed for its protection.

Senior Unsecured Debt

Just like bank debt, the senior unsecured debt might or might not have assets behind it. However, if it does, the assets are not segregated or escrowed. A company can have multiple debt issues at each level of the capital structure. Debt issues with the same seniority are said to be pari passu. Debt issues that are pari passu can be issued at different times and even be denominated in different currencies.

Trade Obligations

Trade obligations include vendors who provide products and services to the company and then send a bill—normally payable in 30 days. Examples of trade obligations include legal fees, accounting fees, other consultants, office supply stores, food vendors, custodian services, and the like. These bills are junior to the senior debt.

Subordinated Debt

The term “subordinated debt” means the debt is junior to the senior debt and is either pari passu with or subordinate to trade obligations. A company can have multiple levels of subordinated debt ranging from senior subordinate to junior subordinate. Subordinate debt almost never has specific collateral escrowed for its protection. Bonds without escrowed collateral are sometimes referred to as debentures.

Convertible Bonds

A convertible security is a debt-equity hybrid that contains an embedded option that grants the investor the right to exchange the security for another type of security. While there are innumerable varieties of convertible securities, the most traditional and common types of convertible securities are bonds and preferred stocks that investors can exchange for a fixed number of shares of the company’s common stock.

Consider a bond issued by XYZ Inc. This bond is issued at par with a 6% coupon and includes an option that allows the bond to be converted at any time into 100 shares of a company’s common stock. At the time the bond is issued, the company’s common is selling for $8 per share and pays no dividend.

No rational investor would buy the bond and immediately exchange it for the stock since the $1,000 bond could only be exchanged for $800 worth of stock (100 shares × $8 per share). However, if a year later the stock is selling for $16 per share, the bond can be converted into $1,600 worth of stock. If the bond was selling at any price below $1,600, an investor could make an immediate risk free (arbitrage) profit by buying the bond, exchanging it for stock, and selling the stock.

In reality, the bond would be worth more than $1,600 because, in addition to being convertible into $1,600 worth of the company’s common stock, it also generates $60 of income per year for its owner. The present value of those future interest payments would have to be added to the conversion value in order to determine the bond’s fair current market value. Before we discuss convertible securities in more detail, it is necessary to become familiar with several terms and ratios related to convertible securities.

Conversion Value

The conversion value is the current market value of the common stock into which the bond converts. It is calculated by multiplying the number of shares into which the bond converts by the current price of the common stock.

Conversion value = number shares × price of the shares

In the XYZ Inc. bond example, the initial conversion value would be:

Conversion value = 100 × $8 = $800

After the stock rose to $16 per share, the conversion value would be:

Conversion value = 100 × $16 = $1,600

Conversion Premium

The conversion premium is the difference between the market value and the conversion value of the bond—expressed on either an absolute or a percentage basis. In the above example the initial conversion premiums would be:

Absolute premium = $1,000 − $800 = $200

Percentage (aka relative) premium = ($1,000 − $800) / $800 = 25%

In the United States, the typical initial conversion premium for convertible bonds is 17% to 30%. The initial conversion premium is determined by the perceived upside potential of the stock and the period of call protection. The greater the stock’s upside and the longer the period of call protection, the higher the conversion premium investors are willing to pay. The conversion premium declines as the bond approaches its call date (see call risk below) or maturity date.

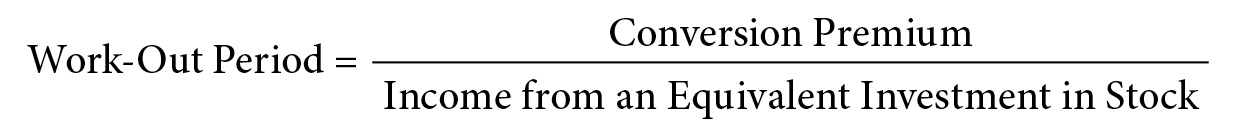

Work-Out Period

One of the most useful ratios for analysis of convertible bonds is the work-out period. The work-out period is a measure of how long it takes for the conversion premium to be amortized by the higher current income generated by the bond. In the XYZ Inc. bond example, the bond generates current income of $60 per year, while the stock generates no income since it pays no dividends. Since the bond has a $200 conversion premium, the work-out period would be:

Work-Out Period = $200 / ($60 − $0) = 3.33 years

If the stock generated a $.10 dividend per year, then the work-out period would be:

Work-Out Period = $200 / ($60—$12.50) = 4.21 years

Note that in this example, the income from the stock is $12.50, since $1,000 would buy 125 shares of stock at $8 each. In order to have a fair comparison, it is necessary to compute the work-out period using the income from an equal investment in both the convertible bond and the underlying common.

The shorter the work-out period, the more attractive the convertible is when compared to the underlying stock. Conservative investors are often willing to buy convertibles with work-out periods as long as 3.5 years, while aggressive investors are often unwilling to accept work-out periods longer than 2.5 years.

Why Investors Like Convertibles

Investors always have to choose between the various ways to invest in a company. They can invest directly by buying the common stock or indirectly by buying a security that converts into the common. Convertibles offer investors numerous advantages relative to investing directly in common stock. Some of these advantages of converts versus common stock include:

- More Senior Security—In the event the company files for bankruptcy, the investors who own the convertible bonds become creditors of the company and, as such, have a senior claim on any remaining assets relative to both the common and preferred stock holders. Of course, in order for this seniority to have any value, the company has to have assets after the more senior creditors, including the government, employees, vendors, and senior debt holders, are all paid in full.

- Higher Current Income—Convertible bonds almost always offer a higher current income than the underlying common stocks. The cash flow from the bond’s interest payments almost always exceeds the dividend payments from an equal size investment in the underlying common stock. For investors that require or desire current income, convertibles are often the more attractive investment alternative.

- Favorable Risk Adjusted Return—Because of the way that the value of the embedded conversion option changes as the price of the underlying instrument changes, the price of the convertible rises by more when the price of the underlying stock rises than the price of the convertible declines when the underlying stock declines. Thus, convertible securities exhibit a positive asymmetric risk-reward pattern in response to a change in the value of the underlying common.

- Automatic Tactical Asset Allocation—One of the most attractive advantages of convertible securities is that they automate one of the most basic and important tactical asset allocation decisions investors have—the decision of how much to allocate to equity versus fixed income. Many market timers try to increase the weighting of stocks in their portfolio when the market is rising and retreat to the higher income and relative safety of bonds when they expect the stock market to decline. Fortunately, for owners of convertible securities, these securities behave more like stocks when the market is rising and more like bonds when the market is either flat or declining. In effect, they automatically tactically reallocate in a way that benefits the investor.

- Outperforming a Benchmark—One way of outperforming an equity benchmark is to substitute a carefully selected portfolio of convertible securities for all or part of the benchmark. It is important to note that outperform means outperforming on a risk adjusted basis. A portfolio of convertibles will usually offer a lower total return than a portfolio of common stocks—but it will also have lower risk. If the return of a portfolio of convertibles is 20% lower than the return of a portfolio of common stocks, but the convertibles only have 60% of the risk of the common stocks, the converts offer 80% of the return for 60% of the risk—hence outperforming on a risk adjusted basis.

While convertible securities offer numerous advantages, they also have some disadvantages that investors need to consider.

- Underperforming the Common—In a down, flat, or slowly rising market, convertible securities will outperform the underlying common. However, in a rapidly rising market, convertible securities will underperform the underlying common stocks.

- Call Risk—Almost every convertible bond is callable. Generally, the bonds are callable either after a certain period of call protection is passed or after the stock price has risen to the point where the conversion option is deeply in the money. When the issuer calls the bond, the investor can lose any remaining conversion premium. Consider the following example:

Suppose the XYZ Inc. bond introduced in the example is purchased as a new issue and that subsequently the underlying stock price rises to $16 a share. Since the conversion value is $1,600 and the bond generates a higher current income, an investor might be willing to pay a $150 premium over conversion value—$1,750 in this example.

However, paying a premium over conversion value can be a disaster if the bond shortly becomes callable. If the bond is called, the investor would have little choice other than to convert the bond into the underlying common. While converting the bond into $1,600 worth of stock beats accepting $1,000 (or $1,030) in cash from the call, it still results in a loss if the bond was purchased at $1750. When the bond is called, the $150 conversion premium ($1750 − $1600) is lost. Therefore, it is important for investors to research the call provisions of convertible securities prior to purchasing a convertible bond or preferred. Investors should not pay a conversion premium that is higher than the present value of the incremental cash flows the investor can expect to receive from the bond before the bond is called.

- Loss of Accrued Interest upon Forced Conversion—When a convertible bond is called, and the investor is effectively forced to convert the bond into the underlying common in order to avoid receiving the call price for the bond, the investor also sacrifices any interest that the bond has accrued. Because they don’t have to pay the accrued interest on bonds that are converted, many companies that have issued convertibles often force conversion by calling the securities just prior to an interest payment date.

Thus, in a forced call an investor can lose both the conversion premium and any accrued interest. Because accrued interest is lost when a convertible is called, it is not uncommon for bonds that are likely to be called to be trading at a price that is equal to their conversion value less their accrued interest.

- Lower Liquidity of Convertibles—Convertible securities have lower liquidity than the underlying common. Investors should use limit orders and build orders over time in order to avoid disturbing the market.

Why Do Issuers Issue Converts?

There are four main reasons why issuers elect to issue convertibles:

- To borrow money at a lower rate. By embedding a conversion option into its debt, companies with decent credit ratings can borrow money at a lower interest rate than they would ordinarily have to pay.

- To borrow money at any rate. For start-up companies, or companies with low credit ratings, embedding a conversion option into its bond may be a necessary incentive to attract lenders, even if the bond offers a higher return.

- To unload a block of stock at a favorable price. Suppose a company, ABC, tries to take over another company, DEF, and, despite accumulating 20% of DEF’s stock, ABC’s takeover fails. Since the takeover failed, DEF’s stock price will be depressed. If ABC was to dump its 20% holding onto the market right after the takeover failed, it would only push the price lower. However, the company that acquired the stock can’t afford to have capital tied up in this block of stock. The solution is for ABC to issue a convertible note that converts into the DEF stock. The company gets its money today and effectively sells the stock at the higher price in the future upon conversion.

- To allow companies to access an additional pool of capital. If the company has already issued equity and straight debt, it has tapped the two largest pools of capital. However, there are investors who only buy converts, so the company has to issue a convert to tap into this market.

Income Bonds

An income bond is a bond where the company only pays interest if it can afford to do so. With all of the bonds above income bonds in the capital structure, the company has an absolute obligation to pay interest on time. If they fail, it causes a default and the bondholders can have the company thrown into bankruptcy to protect their interests. While paying interest on income bonds is optional, management has numerous incentives to make the interest payments in full and on time. If the interest isn’t paid there are:

- No management raises or bonuses

- No stock buybacks or dividends

- No acquisitions