3

Key Lean Tools & Techniques

This chapter outlines the lean tools and techniques I have found to be most useful in an internal audit context. This list is small compared to the full range of lean tools and techniques, but – at this stage – I would rather give a flavour of what there is, rather than swamp the reader (since a full description of these tools could comfortably fill several books).

UNDERSTANDING CUSTOMER NEEDS: THE KANO MODEL

The Kano model (created by Dr Noiaki Kano) is one of the most powerful lean tools for thinking about what customers do and do not value. It involves listening to the “Voice of the Customer” in relation to what is valued and mapping this out for ongoing reference. Of particular interest is the insight that there are different types of value related attributes. The three key types are summarized below:

- Basic requirements or dissatisfiers: This is an attribute or requirement a customer expects as part of a service or product and if it is not present the customer will be dissatisfied or unhappy (e.g. clean sheets in a hotel room, or food in a supermarket that is not mouldy). However, if the attribute is present it will not necessarily result in anything more than a neutral feeling. Although these attributes are basic, this does not mean they will be easy to achieve;

- Performance factors or satisfiers: These are requirements or attributes where the customer value perception will vary depending on the extent to which it is present: for example, “more is better and less is worse” or “easier to use is better and less easy to use is worse.” This could include the ease of checking into a hotel, or the price of a car;

- Delighter or exciter factors: These are requirements or attributes that customers may not expect, but delight them when present (e.g. a complimentary breakfast at a hotel). These delighters need to be given at a sensible cost, but may make the difference between choosing one product or service over another – consider Apple products and the extent to which the look and the feel of these is valued by customers.

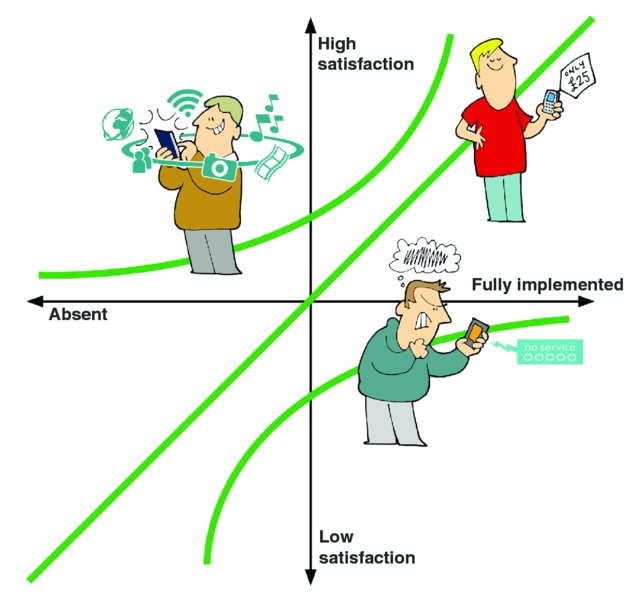

The Kano model can be set out in diagrammatic form as follows:

Figure 3.1 The Kano model, using a mobile phone as an example: delighter – added functionality; satisfier – price; dissatisfier – not working

The Kano model highlights an insight many will recognize: a given amount of time and effort may have a hugely different impact on customer satisfaction. In other words: effort and added value are not always linked in a linear way. Indeed, sometimes providing less can result in a more satisfied customer (e.g. a concise report compared to a longer one).

Thinking about what the customer wants through a Kano approach is central to lean auditing. The aim is to gain a deeper appreciation of what each of the different stakeholders of internal audit want and – just as importantly – what they do not want.

GEMBA

“Gemba” is the Japanese word for the real place (e.g. the place where a news event takes place). In the context of lean it usually means the factory floor or workplace. A key lean technique is to “Go Look See” what is really going on (known as the Gemba Walk). This is the way any waste can be identified, and this is also the place where opportunities for improvement might be identified.

There are some similarities between the Gemba Walk and the western management notion of “management by walking about”, with lean emphasizing the importance of:

- Engaging with what is actually going on when analysing issues or difficulties, with an emphasis on facts rather than opinions; and

- Ensuring that staff and managers pay close attention to what is going on, on a day-to-day basis, as a way of driving improvements in effectiveness and efficiency.

Shigeo Shingo, one of the leading lean practitioners from Toyota sums up the lean Gemba mindset:

“Get a grip on the status quo. The most magnificent improvement scheme would be worthless if your perception of the current situation is in error.”

Gemba has a great affinity with internal audit, since it is all about looking at the reality of what is happening. The challenge for auditors is to apply this approach to their own ways of working. A good example of a Gemba approach would be to pay attention to the difference between how an audit manager or CAE would summarize the audit process (or how it is written in an audit manual), and what it is actually like to carry out an audit assignment in practice.

Value Stream Mapping

In order to improve the way that activities and processes are carried out to deliver value, lean offers a range of tools and techniques to help visualize what is happening so that processes and activities can be improved. Specific approaches include:

- SIPOC mapping

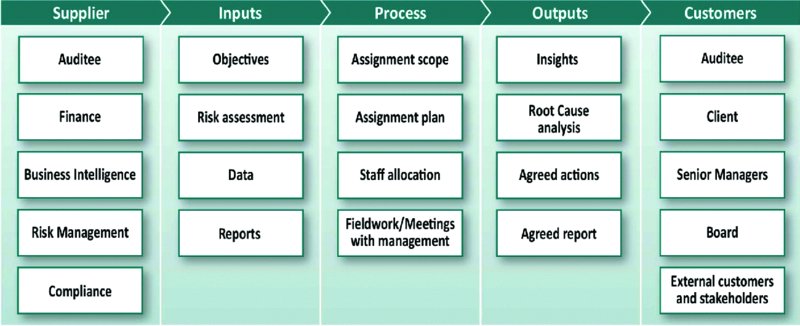

SIPOC refers to Supplier, Input, Process, Output, and Customer and is a framework that can be used to breakdown a process;

In an internal audit context, a number of the key SIPOC elements are set out in Figure 3.2.

- Deployment flowcharts (or Swim Lane diagrams)

Figure 3.2 The SIPOC model as applied to an audit assignment (simplified)

Which can be used to illustrate, amongst other things, the roles of different functions in a process.

Process mapping is a technique familiar to many in internal audit. When applied to internal audit processes it can be a powerful way of drawing out a range of improvement opportunities in audit planning, assignment delivery and the process of drafting, editing and rewriting audit reports.

IDENTIFYING WASTE (MUDA)

Lean principles regard waste (or Muda in Japanese) as being anything a customer would not want to pay for. No matter how normal difficulties, delays or waste seem, lean demands that we pursue waste free ways of working. However, Shigeo Shingo observed:

“The most dangerous kind of waste is the waste we do not recognize.”

Indeed, much of my work with auditors starts with helping them to notice waste in audit activities that seems so normal it has become invisible.

Lean defines the normal waste items that so often get missed. Taichii Ohno of Toyota suggests seven key areas of waste in a production context:

- The waste of overproduction;

- The waste of waiting;

- The waste of unnecessary motions;

- The waste of transporting;

- The waste of over-processing, or inappropriate processing;

- The waste of unnecessary inventory;

- The waste of defects.

In a service context, other forms of waste include:

- The waste of making the wrong product;

- The waste of untapped human potential;

- Excessive information and communication;

- The waste of time;

- The waste of inappropriate systems;

- Wasted energy, resources and other natural resources;

- The waste of (excessive) variation;

- The waste of no follow-through;

- The waste of knowledge.

Other difficulties that can interrupt the flow of value to the customer include:

- Unevenness, or Mura in Japanese;

- Overburden, or Muri in Japanese.

To address the various types of waste that can arise, lean provides a range of tools and techniques, including:

Heijunka

This technique aims to prevent issues arising by smoothing the flow of work. This includes techniques to standardize and sequence what is done.

Jidoka – Also Known as Autonomation

This aims to prevent errors arising. The idea is to create machines, systems and processes that rapidly identify when poor quality occurs because of the impact on the customer as well as the resulting waste and rework that arises from poor quality.

Just in Time

This is a widely known lean technique, and is about delivering the right quality product or service at the right time at an optimal cost.

Andon – Visualization

Lean ways of working require ongoing monitoring of what is going on with clear, visible indicators or metrics. These allow staff and management to identify any issues or difficulties and act on them in a timely manner. In an audit context this is a particularly useful technique when tracking assignments.

Root Cause Analysis (RCA)

RCA is a fundamental technique in lean, and one that should be familiar to internal auditors. Specific RCA methods include:

- The Five Whys: the approach encourages us to question why things are happening, so that the real reasons for difficulties are known, thus maximizing the chances of a proper solution;

- The Fishbone (Ishikawa) diagram: where effects/symptoms are traced back to their causes using a structured framework.

A WORD OF CAUTION ABOUT LEAN TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

In addition to my neutral stance on any specific brand of lean, I want to flag up an important message at the outset in relation to lean tools and techniques: these should be used to enable and facilitate efficient and value adding internal audit work, not become a thing in themselves.

John Earley (Partner, SmartChain International) explains:

“Which lean tools you apply and how you apply them is situation specific. There’s nothing in the lean toolkit that is mandatory. This is where the difference between success and failure could be. You have to be very pragmatic how you apply lean.

To take an analogy: If you are going to hang a door, and you have got a toolbox full of tools, you don’t use every tool in the box. You pick the tool that you need to do the job properly and you make sure they’re in good shape and you know how to use them, and then you do the job, then you put the tools back in the box and wait for the next job.

When applying lean over a period of time, there’s always a progression of things happening and the techniques that you use at one point in time may not be as important at another time. However, the constant factor that runs through that whole thing is the mindset and culture of customer value, efficiency and continuous improvement.”

Norman Marks (GRC thought leader) offers similar advice:

“You don’t have to necessarily go off to Japan and get a black belt in lean. You’re not going to learn about lean internal auditing by going to Toyota and walking through their plant.

My advice is that this is mostly common sense. It’s standing back and saying, I want to be of value to my customer, so what do they need? Not just what I want to give them, but what do they actually need for them to be effective.

Throw out the traditional and replace it with common sense. And just because everybody else is operating in a traditional way, doesn’t mean it’s best.”

References and Other Related Material of Interest

- Kano, N. (1984) Attractive quality and must-be quality. Journal of the Japanese society for quality control.