“You lucky three are this morning’s guinea pigs,” Ricki says. “Kids are more adventurous than these old fuddy-duddies,” she says, nodding to the fishermen’s booth. Charlie Cleave tucks his top lip under, making his front teeth protrude, and hangs his hands under his chin like little rat claws while the guy next to him chuckles.

“Is it . . . actually guinea pig?” Tavi whispers to Miles in horror. “Today’s special?”

“Voilà! Geoduck Scramble!” Ricki announces. She places a plate before each of us.

One of the fuddy-duddies beckons Ricki for coffee. She runs to fetch the pot, leaving us to stare at the scramble.

Gray globs congeal in pockets of pale yellow eggs, a pink oily sheen forming on top of the entire dish that moves in one giant mass when I poke it.

Tavi yanks her phone from her pocket. “Geoduck is shellfish, right?”

“What does that have to do with anything?” I ask frantically.

“She’s Jewish,” says Miles, staring horrified at the plate.

“So am I.”

“She’s kosher,” he clarifies.

“I could be kosher for a day!”

“And as a fellow Jew, Portland,” Tavi says distractedly, “you know that’s not how kosher works. You don’t get to turn it on and off.”

“I know, I know. But c’mon, ask five different rabbis the rules about kashrut and what you can eat on the same plate—or what you can eat at all—and you’ll get five different answers!”

“True. I guess society has modified our rules a little. But not in my family,” Tavi says, taking a quick break from her geoduck search.

“All I know is geoduck definitely lives in a shell.” She points to her phone screen. “Which means it’s shellfish, which means in our house, it’s a big nope.”

Ivan the pug—who for sure does not keep kosher—toddles up as Ricki reappears to check on us. He’s whimpering this morning, swaying unsteadily on his squat legs as he wheezes.

“What’s with him?” I ask.

“Mister Impatient here got into a batch of scramble that was cooling on the countertop,” Ricki says, scolding Ivan. “He’s been retching all night. The vet says—”

“Nature’s taking its course?” Tavi guesses.

Ivan. Poor, sweet Ivan. What could have possessed him to risk it all?

“Now you kids eat up, and I want honest feedback only!” she says as she disappears into the kitchen. “Tryouts are only three weeks away.”

I glance at the double doors on the other side of the restaurant.

“Wait here,” I say, standing up. “I have an idea.”

When I peek my head into Toby’s shop, I find him rearranging the lotions and soaps.

“Ah, Mr. Greenburg! Such a pleasure to see you again,” he says.

“Toby, we need you,” I tell him.

“Oh, well, it’s nice to be needed,” he replies.

“We have a geoduck situation,” I say.

“Ahh,” Toby says calmly. “Say no more.”

He accompanies me into the restaurant and beckons Ricki from the kitchen.

“Bad news, darling,” he says. “Could I steal you away for a moment? The young adults—they’re so sweet; they didn’t want to offend you—”

What’s he doing? He’s going to tell her the truth? Holy heifers, no!

“Actually, Toby, can I talk to you for a sec—?” I try to interrupt him.

“Gus, Ricki needs to know.”

People already think that Mom and I are comet-worshipping doll head collectors. Now I’m going to offend Ricki, maybe the nicest person on Nameless Island aside from Toby. What else could make me more hated? Maybe there’s a baby nearby I could steal some candy from.

Toby whispers something in Ricki’s ear.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Ricki cries, yanking the plates away from us, sloshing geoduck to the edges of the table.

This is bad. This is so much worse than bad. When Mom finds out I’ve offended Ricki, she’s going to ground me for life—again. Is there a period longer than life? If there is, she’s going to ground me for that long.

“It’s okay,” I say, trying to grasp at the plate’s edge, but my hand sinks into the gooey mess at its edge, slopping the scramble over the side and into my lap.

“No, no,” Ricki protests. “Absolutely not, young man!”

I’m toast. I’m burned toast. I’m scorched toast. Freedom is but a distant memory already. Goodbye, cruel world.

Despite his, Ivan is still following in Ricki’s path, licking up the drippings from my plate as they hit the floor. Even he’s willing to throw himself upon the sacrificial scramble rather than offend sweet Ricki.

When she returns from the kitchen empty handed, I’m ready to do anything to make it up to Ricki.

“Please,” I tell Ricki, “I’m so sorry.”

Ricki stares at me in disbelief, blinking rapidly like she has something caught in her eye. Toby is staring at me, too, but he’s giving me a different look, not one of disbelief. More like a “You’re ruining this” kind of look.

“Dear child, why on earth would you be sorry?” Ricki asks me. “I’m the one who should be apologizing to you! If I’d known Miles’s mom had a big lunch planned at Park’s on Park for you guys today, I wouldn’t have insisted you have such a big breakfast!”

Toby’s face never flinches. He’s a genius.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Ricki turns to Miles.

“The, er, geoduck scramble just smelled too . . . delicious?” Miles tries.

Toby shoots him a look that says we should probably leave the storytelling to him from now on. I can’t exactly say I disagree.

We thank Ricki for her understanding and make a quick getaway into Toby’s shop for some handwashing to rid ourselves of the geoduck scent. Toby latches the double doors and closes the curtains over the panes of glass.

“I owe you my life,” I sigh to Toby. “Again.”

“You and your mom get that manor in tip-top shape and bring tourists back to Nameless,” Toby says, “and we’ll call it even.”

“Fair enough,” I say, taking in Toby’s cluttered shelves as I wander to the back of the store where stacks of old albums are collecting dust. “Guess the renovation really is that important.”

“Well, the locals keep us afloat, you know,” Toby says, referring to himself and the Rickis of the island. “But the tours were a big draw. And the fish derbies. Once they moved those to Rhodi, well . . .”

Toby goes quiet, and rather than continue to press on the bruise, I leaf through albums. I’m actually surprised at how old some of them are. Many are black and white, but some are that old yellowed color, with women in huge skirts and men dressed like . . . well, like Toby.

“Hey, come look at these,” I motion to Tavi while Miles samples the various lotions.

“Toby, do these pictures date back to the Rothams’ time?” she asks.

“Hmmm?” Toby says, peering over our shoulders. “Ah, yes, it appears so.”

Tavi and I have to be thinking the same thing.

“Was it only Peter?” I blurt.

“Pardon?” Toby asks.

Tavi clarifies: “The Rothams. Peter was their only child, right? And he lived to old age?”

Toby smooths his goatee. “Yes, that’s right.”

“Does the name Felix mean anything to you?” I ask.

Toby’s forehead wrinkles. “Felix,” he says, allowing a long time to pass before answering. “Now that you mention it, something about that name does strike a chord . . . why?”

Tavi and I exchange another glance. I don’t know why, but I don’t want to tell anyone else about the notches on the basement door. Not yet.

“Just something someone said,” I lie, and Toby’s eyes narrow the tiniest bit.

I can tell he’s not satisfied by my answer, but lucky for us, Toby likes a good mystery.

“Now it’s going to bother me until I figure it out,” he sighs. “Let me do some digging. I’m sure something back here holds the answer to your Felix quandary.”

I don’t doubt it. I flip through more pictures and find more copies of the same yellowed portrait of the Rothams in front of their newly built manor, the same portrait I’ve seen so many times with the family of three. Only three.

I stare and stare at the boy named Peter, the one who Tavi and Toby said lived to be old, so he couldn’t possibly be the angry, broken boy who won’t leave me alone, because that would mean he would have died young. I think back to the notches on the basement door, the ones that stop suddenly at age nine.

Felix. Is the broken boy Felix? If he is, how is Felix related to Peter?

“Why won’t you show me how you died?” I whisper.

Every once in a while, life throws me a bone. Tonight’s bone might just be the one that fixes the broken boy.

“I have a conundrum,” Mom says over garlic long beans and beef and broccoli. “The Council of South Sound Historical Homes rearranged their annual meeting calendar, which puts Dot LeBeau and Eric Evergreen in Tacoma a full two months earlier than they were supposed to be.”

“Dot LeBeau and Eric Evergreen don’t sound like real people,” I say.

“Oh, they’re real,” Mom says. “They’re basically the Rothams and the Cleaves of Rhodi Island. They represent the founding families over there. And when it comes to the South Sound islands, they hold a lot of sway.”

“Wait, they’re the ones you need to show some progress to?” I ask.

“Some of the most important ones, yeah,” Mom says, chewing on her bottom lip.

“But they’re gonna see—” I start.

Mom’s eyes shift down and to the side. “We’re having the entire place extensively fumigated for a rat infestation,” she says.

“Really?” I ask.

She keeps her eyes averted. “We might,” she says. “Eventually.”

This is me keeping my mouth shut.

“You did say you saw a rat.”

“I’m not saying anything.”

“You’re judging me with your eyes,” she says.

“How would you know? You’re not looking at me.”

“I can feel you,” she says.

Like I’m going to judge Mom for lying. I’m plotting my next crime at this exact moment. If this Dot LeBeau and Eric Evergreen are in Tacoma this weekend, maybe that means . . .

“Okay, so. I have to stay the night in Tacoma this Saturday,” Mom says.

Bingo.

“So what’s the big deal?” I ask while eating a long bean, playing it cool.

Mom purses her lips. “It’s kind of short notice to find you a sitter.”

This is normally the part where (1) I’d argue that I’m twelve and old enough to be the sitter, (2) I’m mature enough to be left alone, and (3) I’m not a baby, stop treating me like a baby, you always treat me like a baby. But seeing as I still don’t know why the broken boy is—as far as I know—set on hurting me, I’m not super excited for a solo sleepover with him either.

Also, there’s no one to ask to stay over and watch me. It’s not like Mom’s made friends here. But I’ve made two, and this is where that bone I was talking about comes in.

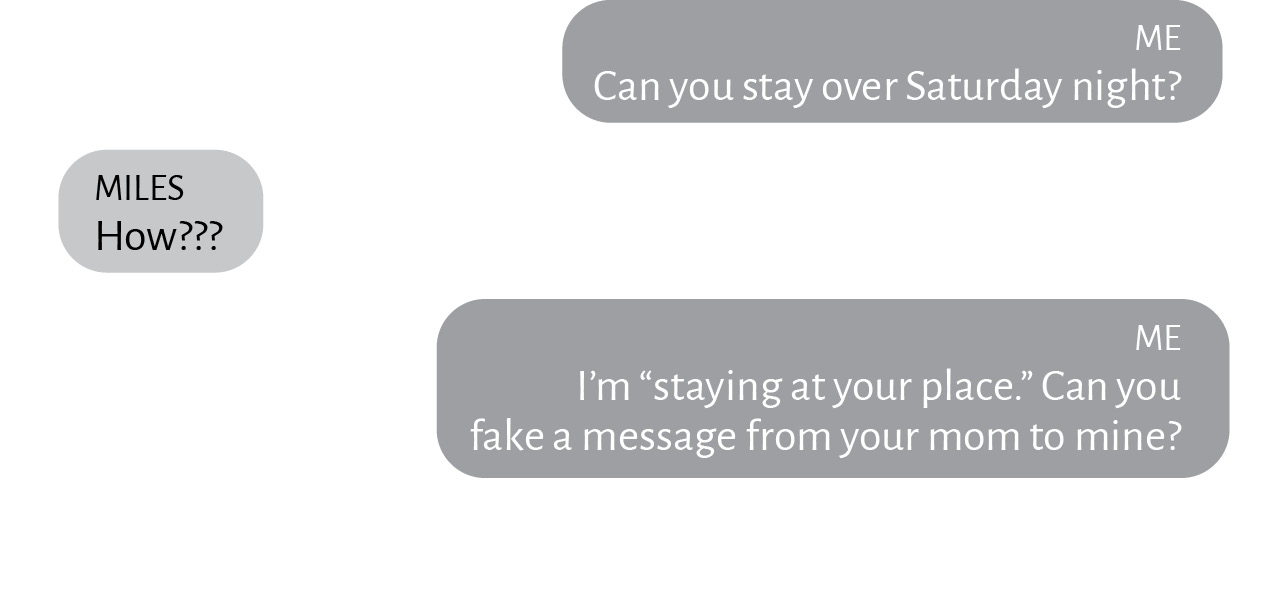

“Why don’t I stay over at Miles’s house for the night?”

“Do you think his parents would be okay with that?”

“Yeah, why not?”

Her face falls. “I haven’t met them. I should at least have a conversation—”

“No!”

Mom eyes me.

“Uh, it’s just that his parents are really busy running their restaurant on Rhodi. You know, Park’s on Park? Don’t worry; I’ll ask Miles to have his mom send you a message.”

“Okaaay,” she says, her eyes narrowing.

“I’m sure they’ll be cool with it. Don’t worry.”

“When you keep saying ‘Don’t worry,’ it makes me worry.”

“I’m gonna text him now,” I say. I toss my scraps into the compost and slide to the sofa to grab my phone.