Squiddy’s Seattle apartment is filled with awesomely weird art, a huge vinyl collection, mint-green appliances, and a giant circular sofa in the living room that takes up most of the floor. Miles and I are sleeping there. The only reason we know that is because Squiddy threw a pile of soft blankets and pillows onto it and pointed.

She didn’t say a single word when she picked us up on the corner with Tavi. We let Tavi do all the talking while Squiddy gave us the longest stare of my life. I might have peed my pants a little. Then she told us to call our moms.

Tavi disappeared into her bedroom, Squiddy disappeared into hers, and Miles and I lay side-by-side on the massive round couch, waiting until the last possible second to make our calls.

“You wanna go first?” I ask him.

“No,” he says, but picks up his phone anyway, and I scoot a little farther to my side to give him privacy. Not that I need to; it’s all in Korean, and it’s mostly his mom screaming. But I wait until he’s finished so he can properly hear his scolding. Then I dial my mom.

“Are you hurt?” she asks me when she picks up. Her voice is jumpy, and for some reason, the first thing I think about is the little green line on Miles’s EFR.

“No,” I say, whispering because it feels like the right amount of noise to make.

“Where are you?”

“Seattle,” I reply. I swallow, but my throat dries up immediately.

I wait for the next question, but she’s quiet. I don’t think she knows what else to ask.

“I’m with Tavi’s mom and Miles at her apartment.”

“I know,” Mom says. “Her other mom called me.”

I stare out the window at the sky; it’s swirling clouds turning coral with the setting sun. The parents have been trading phone calls, texting, pacing the dock.

I scared her.

“Mom, I’m really so—”

There’s a silence so long I think I’ve lost the connection. Or maybe she’s hung up.

“Gus, I’ll meet you on the dock in the morning,” she finally says.

“Okay, Mom.”

I hang on the phone because that isn’t all I want to say. I want to finish the “sorry,” tell her how stupid I am. I want her to know that it wasn’t all for nothing—I cracked the mystery, and it was more important than she knows. I should have trusted her to understand. I want to tell her that maybe if I’d been less worried about her freaking out over my broken brain, I might have been able to tell her the truth—that what’s been haunting me is real; it’s not in my head. It isn’t because Dad is gone.

I wonder whether all of this wouldn’t have happened if Dad were here. I want to ask her, but I know not to. It’s not like she’d know the answer to that anyway. Instead, I wait for her to say more before I hang up. Anything else would be better than nothing.

“Good night, Gus.” That’s all I get.

The next morning, the front desk of the Acacia Grove Residential Hospice is empty as we drag our feet behind Tavi’s Squiddy. I’ve been keeping my eyes fixed squarely on Squiddy’s box braids the entire morning, counting the number of times the beads click when she walks. For some reason, this small task is the only thing soothing my nerves. I didn’t sleep at all, even though the round sofa was squishy and the blankets were soft.

Squiddy has demanded we pay our respects to the staff and guests we “so rudely took advantage of” before we leave Seattle. We practically mowed Russell down on our way out, and we couldn’t spare a “thanks” to poor Ms. Walker, so our apology tour should start here.

Squiddy turns to us. “Stay here,” she says, then clicks down the linoleum hall. She makes it three doors down before running into Russell, and this might be the one and only time Russell has ever been caught off guard.

“Whoa! Sorry, didn’t know we were expecting anyone to—”

Then he catches sight of us.

“Ms. Hannah,” he says solemnly, bowing his head gracefully toward Tavi.

“Hi,” Tavi says.

“Excuse me?” Squiddy says.

“How did you know to come?” Russell says to Tavi, and now we’re all confused.

“What do you mean?” says Tavi.

“I’d like to know that as well,” Squiddy says.

“What happened?” Tavi asks. “Is it Ms. Walker?”

Russell’s eyes cast downward, and his hands clasp in front of his large chest.

“She didn’t feel a thing,” he says when he meets Tavi’s gaze. “Drifted off in her sleep.”

Tavi nods, and we all take a quiet moment for Ms. Walker until we hear shuffling down the hall. The front desk receptionist from yesterday rounds the corner with a box in his hands.

“Oh!” he says upon seeing Tavi. “Wow, this is lucky.” Then he covers his mouth. “I mean, not lucky that she’s, you know . . . poor Ms. Walker.”

“We wanted to apologize for whatever disturbance we may have caused yesterday, don’t we?” Squiddy interrupts, casting the three of us a stern look. We all nod.

Russell is the first to reply. “Yesterday was the happiest I’ve seen Judy in months.”

Squiddy doesn’t seem impressed. “I’m glad, but they shouldn’t have done what they did.”

We’re about to leave when the front desk receptionist stops us. “When I said it’s lucky you came back—” He lifts the box he’d been carrying, and for the first time, I notice it says J. Walker on the side of it. “I tried to pick the things she cared about the most.”

Tavi’s Squiddy closes her eyes and shakes her head. “We’re not family,” she clarifies.

The nurse looks surprised. “Of course not.”

“But why—?”

“You already knew when you walked in yesterday that she was one of our,” he searches his brain for the right phrase, “solitary guests.”

Russell puts it more bluntly. “Without next of kin, her things will go to the state.”

“Then you should keep her things,” Tavi says to Russell. “You were closest to her.”

But Russell shakes his head. “Against corporate policy. They’re our patients, not our benefactors.”

Squiddy gingerly takes the box from the receptionist and passes it to Tavi.

“It’s the least we can do,” Squiddy says.

Tavi takes the box from Squiddy and sets it gingerly on a table in the otherwise empty lobby. Something about the lobby being empty both times we’ve been here makes me sad. I wish there were people milling around, younger family members waiting to see their relatives, old friends popping by to see residents, kids bringing pictures to their grandparents. Instead, all I see are stacked board games and magazines that look like they haven’t been touched in months.

Tavi seems to be looking for something in the box, and after a few minutes of rifling around, she emerges from her dig looking victorious. Then she turns to find Russell, who is still lingering in the hallway, leaning against the wall, his face unreadable.

Tavi walks slowly over to him and extends her hand.

“I’ll bet she would have wanted you to have this,” she says, and Russell peers down to see her offering.

It’s a simple gold band with a light aquamarine stone in the middle. I recognize it from yesterday. It was hanging loosely on Ms. Walker’s bony left ring finger—her wedding band.

Russell takes the ring from Tavi’s hand. An ache in my heart I’ve never felt before spreads through the rest of my body as I watch a single tear drop from Russell’s eye and trickle down his cheek. He closes his hand over the ring and holds it tight.

Miles’s mom, Tavi’s mom, and my mom wait at the Rhodi dock, sharing the exact same expression. I guess anger looks like anger on everyone.

Tavi’s mom goes first.

“I was scared to death. You can’t imagine how that feels!”

Miles’s mom says nothing. He glances back at me with a look that says “goodbye forever.”

Mom doesn’t wait for me to reach her. She knows I’ll follow. Or maybe she doesn’t care.

When we get home, she closes the door softly, walks to the living room, and stares out the window at Nameless Cemetery with all its blank markers. She sits down on the purple sofa, and I sit on the other end. It takes her a long time to face me, and when she does, she says the last thing I expect her to say.

“I owe you an apology,” she says.

It’s a trick. Some sort of test.

“I should never have taken this job.”

Huh?

“Mom, I’m the one who—”

“Yes, you did. I’m not sure how I’ll be able to trust you again. I’ve never been more frightened than when I got off the ferry in Rhodi and you weren’t there.”

Tears fill her sunken gray eyes, and my stomach twists hard enough to make me gasp.

“I thought you might not—”

She tries again, but she can’t get the words out. Come home. She thought that I might not come home. Like Dad. She thought I’d disappeared like Dad.

“Mom, I—”

“It’s my fault,” she says, and I still can’t understand why she’s saying that.

Her voice turns steady, almost robotic.

“This move was too much. It was too sudden. I’ve been trying to convince myself that we needed this, that it was the right decision and it would be our way to a new . . .” She takes a deep breath, steadies herself again. “A new life. That’s what I wanted for us.”

“I thought so too,” I say.

But I realize she’s right: it was too soon. Dad’s absence is like a wound that keeps opening. Now, sitting here with Mom, being honest with each other for the first time since we arrived on Nameless, I know that neither of us can pretend anymore. The move here wasn’t a new start. It isn’t going to make it easier for her to think Dad is dead or make it easier for me to think he’s coming back, and, either way, there’s no turning back now. Portland is behind us, and Rotham is our new home.

Mom hugs me hard. She buries her face in the back of my neck. She sniffs and tells me I’m grounded for life.

“I know,” I say.

I spend the rest of the day wondering how bad it is for Tavi and Miles, whether everyone at school will be talking tomorrow about how we messed up, whether anyone will even know we were missing. I can’t tell whether this is the best or worst way to start at a new school. I’d ask Miles, but by the time Mom returns my phone, humans will probably be communicating via wormhole instead of text.

As anxious as the school stuff makes me, it feels better to think about that than it does to think about yesterday. With all the drama in Seattle and the trouble we got into, I’ve been able to forget the whole reason we were there in the first place.

Now that the dust has settled and I’m marinating in my endless punishment, there’s no hiding from the awful truth we learned in Judy Walker’s room: the broken boy is Felix Walker, a child abandoned by his parents and hidden by his guilty relatives. A kid who was, at best, a burden to his Aunt and Uncle Rotham and Cousin Peter, who still had to maintain the appearance of a legitimate business, whose death was probably more of a relief than a tragedy to anyone who knew about it.

Whose own parents could never reclaim him—with his dad in jail and his mother on the run from the law. No wonder he’s so angry.

I’ve lain on the sofa for the whole day, but all I’ve done is cup the metal medallion of overlapping letters in my hand.

“WB,” I mutter to myself on occasion. That must be what the letters are, though it’s still hard to decipher when I look at the charm.

Walker Brewers, that has to be what the letters stand for. I squeeze the medallion in my fist hard enough to make an impression, remembering how I did the same to the broken chain from Judy Walker’s box.

That photo with little Felix and his mom, Evie, who left him in the middle of the night after his dad was arrested. That necklace with the circular charm she wore—was it this? Did Felix keep it for all those years he hid in the attic of the Rothams’ house, waiting for his mom to come back for him? If they kept him behind the little arched door upstairs, why keep luring me to the closet in the sewing room?

Are these the horrible truths the broken boy couldn’t show me? That he was a burden? A secret? That in the end, he was disposable?

“Why? Why couldn’t you show me?” I ask the musty air of Rotham Manor.

In the evening, Mom tries to call me to the kitchen for dinner, but I’m not hungry. I haven’t been hungry all day. We haven’t spoken since our talk on the sofa. I’m not sure what else there is to say to each other right now. She leaves me a sandwich on the table, and finally, I hear her go upstairs and close her door for bed. At some point, the manor falls into darkness, but like so many other nights, I can’t sleep, so I put on my regular clothes instead of my usual puppy heart flannel jammies, and I pace.

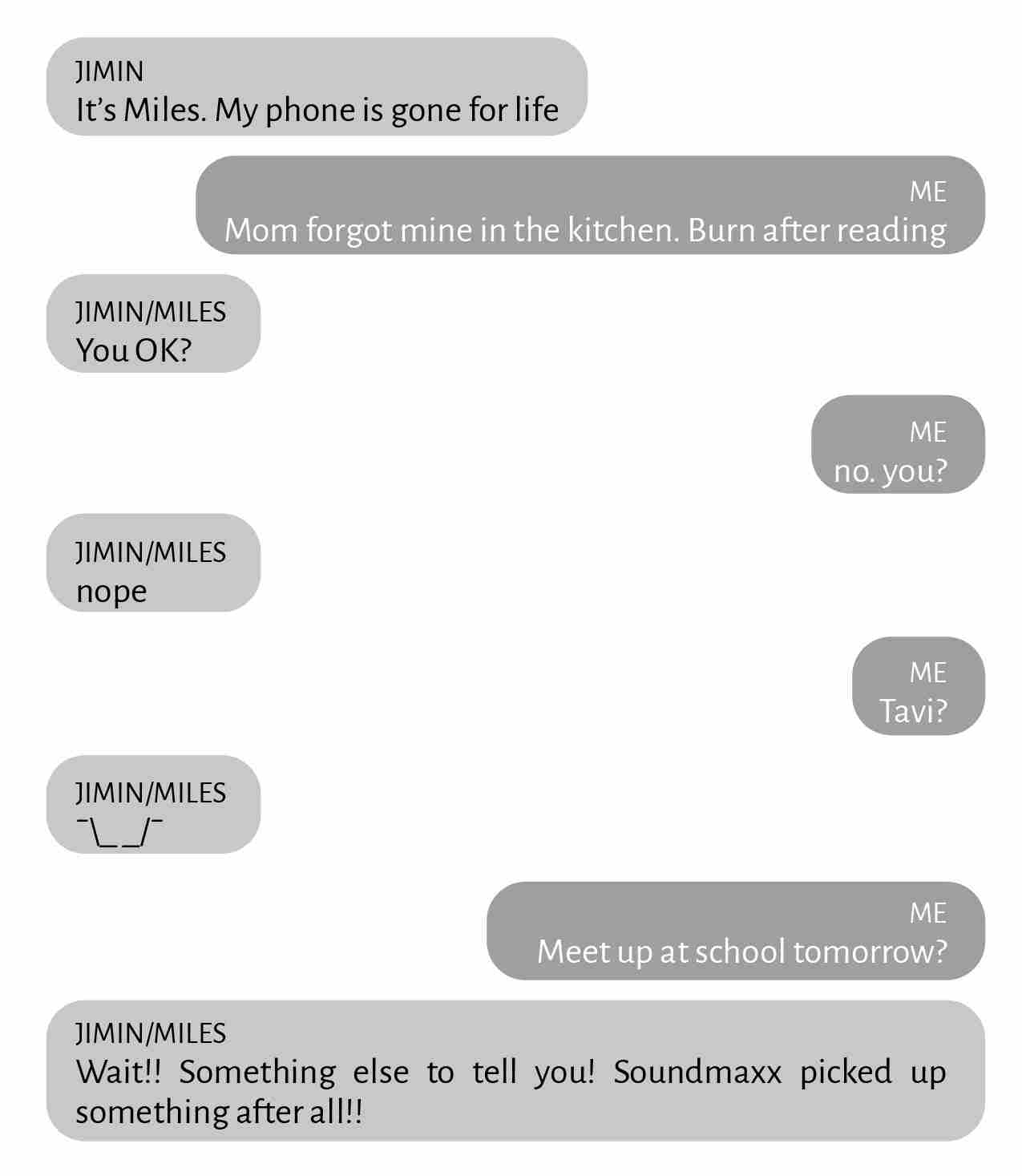

When I make my way past the kitchen table, I hear my phone vibrate.

I freeze, leaning into the foyer and sneaking a look up the staircase to see whether it’s a trick. I half expect to see Mom with her hand wrapped around a string attached to my phone case, ready to yank it out of my hand the second I go for it.

But the staircase is dark. No Mom, no string.

My phone buzzes again, the screen glowing against the wood of the table where it lies facedown, exactly where Mom forgot it. I lunge for it, fumbling and nearly dropping it to the ground before catching it at the last second.

My stomach drops to the floor. Without thinking, I glance over my shoulder toward the pitch-black hallway leading to the sewing room. All is quiet.

Miles knows I’m not actually irritated with him. It’s the opposite, in fact. Something about hearing from him has given me the last nudge to do what I’ve been trying to scrape together the courage to do all day.

I uncurl my fingers and glare down at the overlapping silver letters in my palm. Little Felix Walker, abandoned in the night, held onto his mother’s charm as tight as he held to the hope that she’d come back for him. He believed until the moment he fell from his attic prison.

A broken boy from abandonment and shame.

Now I understand the anger and the clenched fists and the words he couldn’t get out.

I wait until the sun is just creeping over the rough waters of the sound before I tiptoe to the heavy double doors and open them as quietly as I can, making sure to keep a tight grip on the silver Walker Brewers medallion that his mom must have given him as a promise. I lock the front doors behind me and grab the keys to our golf cart, windbreaker zipped and dinghy keys pocketed.

By the time I park the cart at the docks, there’s no doubt left in my mind. I know exactly what to do. I unknot the boat from its slip and turn the ignition. Then I steer to the midpoint between Nameless and Rhodi Islands, buoyed by the intoxicating fragrance of the South Sound that no longer makes me sick.

For once in my life, I understand a ghost. I understand him more than any of the others. This ghost—this broken boy—isn’t so different from me. He knew the special kind of ache that comes with missing a parent. You can cry over death, but the cruelty of hope is bottomless.

Which is why, when I reach the middle distance between Nameless Island and Rhodi, I stop the motor of the dinghy, cup my hand around the charm, and throw it as hard as I can into the dark gray waters of the South Sound.

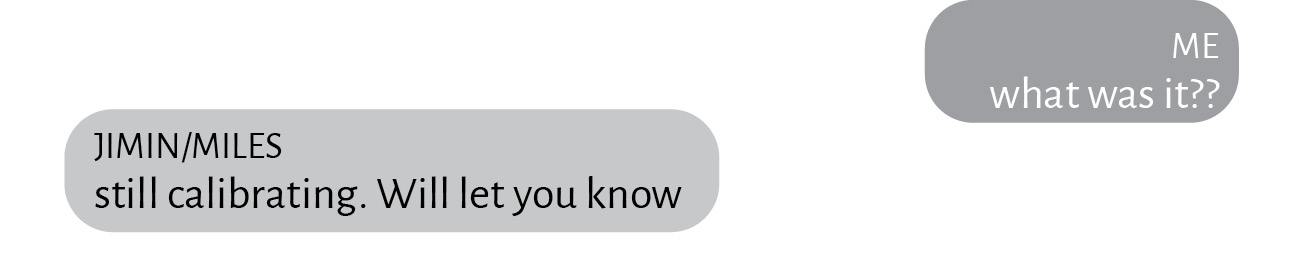

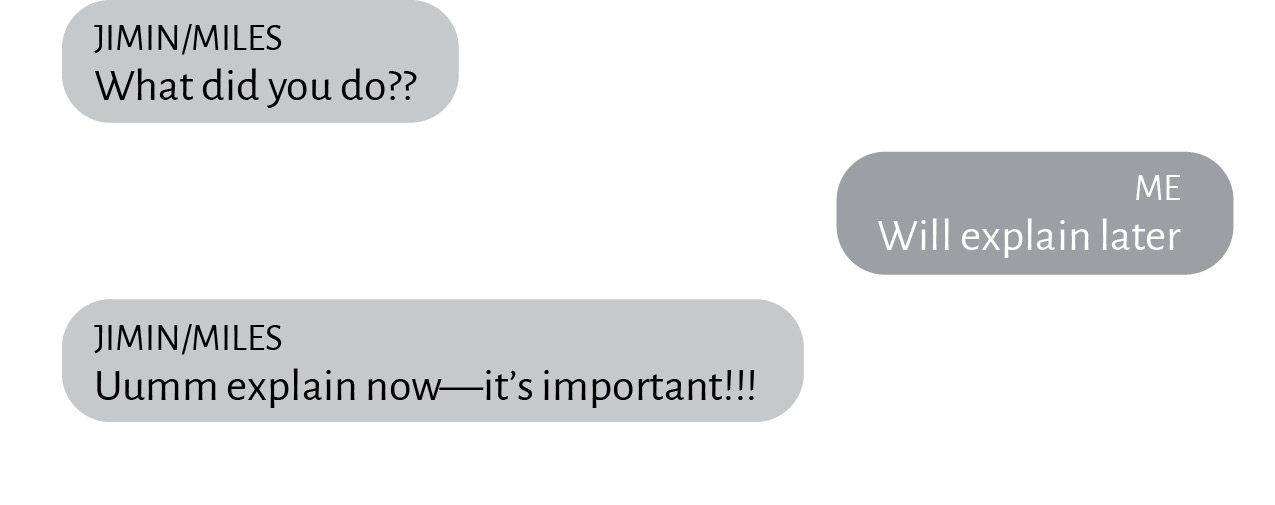

Back at the manor, I slip under the covers on the sofa and pull my contraband phone from my back pocket, texting Miles on Jimin’s phone.

It’s just past dawn, but he responds right away.

I’m about to ask why when the phone is ripped away from my hands.

“Mom, I can explain—”

But it isn’t Mom.

Rotting, skinless fingers grasp the silk cord around my neck, yanking me from my pillow and choking off my words. The feeling on my lungs, the putrid air, the lidless eyes of pure, unfiltered hate—the broken boy’s clacking teeth are close to my face.

I laid you to rest! I set you free! I want to tell him, but I can’t move my lips.

Threaded through his decayed fingers, my silk cord begins to fray, but beside the knot, resting on the broken boy’s exposed knuckle, lies a coin.

A flat copper penny—the very first treasure I found with Dad. The broken boy has returned with it.

“My coin,” I manage to croak out. “But I lost it.”

The broken boy’s breath is hot and rotten, stealing my own breath from my lungs.

“Yes, and I’ve found it.”

The knot in my stomach twists as he draws me closer.

But the penny.

“Where is he? Where’s my dad?” I gasp.

“That isn’t the question,” the boy snarls. “The question is now that I’ve found your treasure, where is the treasure you stole from ME?”