CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FOUR CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FOUR

‘Everyone has heard the story of the little boy who cried wolf. But very few have heard of the classic psychology experiment this famous folktale inspired. Want me to tell you about it?’

‘Go on,’ says Andy, chucking a knackered piece of carburettor into an already overflowing bin. ‘I’m all ears.’

We’re in his garage and he’s dismantling his latest acquisition – a Moto Guzzi V7 Racer.

‘OK,’ I say. ‘Listen up. Imagine that there are twenty telephone boxes all in a line. I show you into one of these telephone boxes and close the door. In front of you, where the telephone would usually be, is a big red button. Underneath the button are the following instructions:

You must remain in this telephone box for ten minutes without pressing this button. There are nineteen other people in the same position as you in the other boxes.

If, after the ten minutes is up, no one has pressed the button, everyone will receive £10,000.

But if, before the ten minutes is up, someone does press the button, then the experiment will immediately terminate – with the person who pushed the button receiving £2,500 and everyone else getting nothing.

The time will commence when the button lights up.

Thank you for participating in this study.

‘All of a sudden, while you are still trying to get your head around the ins and outs of the deal, the button lights up. What do you do?’

Andy looks up, his face spattered with gunk.

‘I’d push the button,’ he says.

‘What?’ I say, open-mouthed. ‘No, you wouldn’t!’

He rubs his nose with his oily, grease-black hands and screws his face up at me as if I’m demented. It’s a comical scene. He looks like the naughty kid in the middle of a finger-painting class.

‘Of course I would,’ he repeats. ‘I’d push the fucking button. Why wouldn’t I?’

I’m stunned.

This fiendish experiment is known as the Wolf’s Dilemma – for obvious reasons. It is a brilliant window on to the fraught, troubled, and often stormy relationship between the way we THINK and the way we FEEL.

Between LOGIC and EMOTION.

Between HEAD and HEART.

When most people are asked this question, they say that they’d do nothing. They’d ‘play the game’ and hold out for the full ten minutes. And why not? If everyone thinks the same and ‘pulls together’, then each player goes home ten grand richer.

But the question, of course, which obviously occurred to Andy, is:

Will everyone think the same?

What if one of the other nineteen players decided that they wanted to save the researcher a couple of hundred thousand quid and pressed the button? Or what if one was paranoid that everyone else was going to gang up against them and decided to press it themselves to beat them at their own game? Or what if one simply pressed the button by accident?

When you go down this road – the road Andy immediately went down – the doubts start creeping in.

What are the chances that one of the other nineteen players will:

•freak out,

•have issues, or

•just be plain selfish and press the button?

The odds are fairly high.

Moreover, what are the chances that one of the other nineteen players won’t have exactly the same thought themselves? And press the button!

In fact, seeing that it’s already occurred to YOU, what are the chances that one of the other players isn’t having exactly that thought right now? And is going to press the button right now?

When you weigh all of this up you come to a startling conclusion. The conclusion that Andy came to. Though your HEART might tell you to hold out for the full ten minutes, to pull together, to trust your fellow competitors and have a bit of faith in humanity, the cold, clinical, LOGICAL thing to do is to press the button as soon as it lights up.

The others may hate you. But so what? You’re walking away with £2,500. And they’re walking away with nothing. You’d have felt the same if you’d been in their position. But you’re not. You’re smart. You cut through the sentiment and worked out the correct strategy.

Or you would’ve done, at least, if you were a psychopath like Andy!

There are many ways to avoid success in life. But if you’re really serious about it you might just want to try procrastination.

Procrastination can be defined as ‘putting off activities that were planned or scheduled for activities that are of a lesser importance’. And with the advent of modern technology – Angry Birds, Xboxes, Facebook and Twitter – it’s steadily on the increase.

In the late 1970s, roughly 5 per cent of the population thought of themselves as chronic procrastinators whereas today that figure hovers around 25 per cent.

GOOD PSYCHOPATHS, like Andy, are clearly not among them.

But here’s the deal. Though it may offer temporary relief when you’re doing it, every time you procrastinate you sabotage yourself. You place obstacles in your own path. You actually make choices that IMPAIR, rather than ENHANCE, your performance.

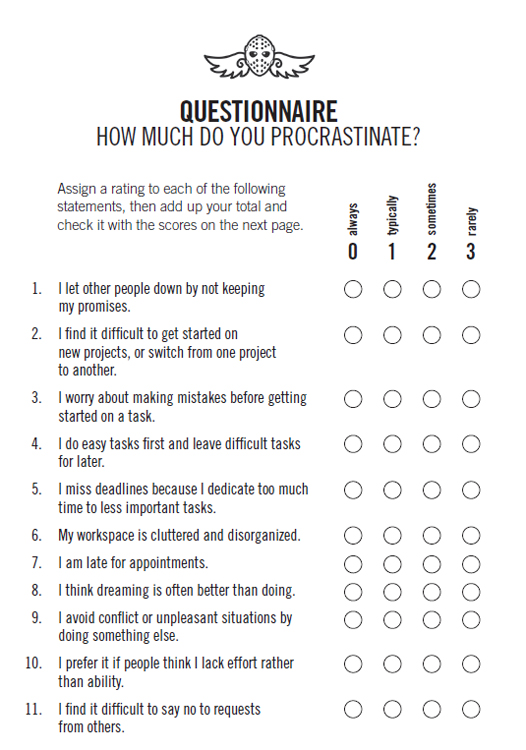

Procrastination costs billions of pounds a year in lost profits; decreases personal effectiveness; destroys teamwork by shifting your responsibility on to others, who become resentful; has a negative effect on health (studies have shown that students who are chronic procrastinators have weaker immune systems and report more coldand flu-like symptoms than those who aren’t). And it cuts across all areas of your life. Below is a list of some of the most common things people procrastinate over. Do any of these sound like you? If they do, you may wish to take the questionnaire at the end of this chapter to see how bad you’ve got it.fn1 (Andy scored zero.)

1.Going to the doctor.

2.Calling your family and friends.

3.Paying your bills.

4.Answering your emails.

5.Going on a diet.

6.Leaving on time.

7.Getting fit.

8.Telling the truth.

9.Apologizing.

10.Saying, ‘I love you.’

11.Starting your own business.

12.Looking for a new job.

13.Doing the laundry.

14.Cleaning the dishes.

15.Asking a favour.

16.Giving up smoking.

17.Getting married.

18.Shopping for groceries.

19.Taking the rubbish out.

20.Ending a relationship.

Of course, at some time or another, we all procrastinate. We all have a tendency to take the easy way out and put the hard stuff off until later. And, moreover, it seems to be perfectly natural.

As he sets about scrubbing some sparkplugs with a manky old toothbrush, I tell Andy about a study that was conducted recently. Participants were presented with a list of twenty-four movies and were asked to make three choices:

•Which one they wanted to watch RIGHT AWAY.

•Which one they wanted to watch in TWO DAYS, and

•Which one they wanted to watch TWO DAYS AFTER THAT.

The movies were split into various types. Some were lighthearted like Sleepless in Seattle or Mrs. Doubtfire. Some were a bit more highbrow, such as Schindler’s List or The Piano. In other words, participants were given a choice between movies that were fun and forgettable and movies that were meaningful and memorable. Movies that could be watched without effort, and those that required higher levels of viewer concentration and commitment.

‘Which ones do you think they went for?’

This gets Andy’s attention and he stops scrubbing for a moment.

‘Unsurprisingly,’ I say, ‘most people went for Schindler’s List as one of their three choices. I mean, it’s widely regarded as one of the best films ever made. But here’s the deal. Despite the fact that it’s one of the best films ever made, it didn’t make it on to most people’s list for the first showing. Instead, people tended to pick lighthearted or action flicks for their first sitting, with only 44 per cent going for the loftier stuff first.’

‘And why’s that?’ he asks.

‘Simple. The heavier gear was thought to require more concentration and effort to watch, and so was put on the backburner for later. In fact, talking of later, people chose more serious movies 63 per cent of the time for their second movie and 71 per cent of the time for their third.

‘And when the researchers did the experiment again with a slight modification – this time participants were told that they had to watch all three of their selections one after the other – Schindler’s List was 13 times less likely to be chosen at all.’

‘OK, OK,’ says Andy. ‘Don’t get too excited – you’ll knock yourself out. That’s the problem with you geeks. Soon as numbers get involved you start hyperventilating.’

‘Fair enough,’ I say. ‘But it’s interesting, isn’t it? Even when we’re doing something we enjoy – such as watching movies – we often put off harder, more demanding activities – even though they might be great – for activities that will give us that instant fix.’

Of course, knowing procrastination when we see it is one thing. Understanding WHY we do it or what makes the habit BETTER or WORSE is another. Science, however, is beginning to come up with some answers. And it’s time to check them out.

No, not later. NOW. You can’t put this off any longer!

When you ask people the question WHY, exactly, they wouldn’t press the button in the Wolf’s Dilemma immediately, WHY they wouldn’t jump at the chance to win £2,500, they typically come up with two different types of reason.

•I’d need more time to weigh up the pros and cons.

•I’d be worried about how it might look to the other players.

Both of which are fair enough. We love to veg out in our COMFORT ZONES. Our brains put their little fear kettles on, whip out their little fear chocolates, and whisper between our ears: ‘Now’s not the time. You can do this, no problem. But, just to be on the safe side, it’s probably best to wait. Have a cup of No Rush coffee and a Perfect Moment soft centre and see how things pan out.’

Whatever the reason, the bottom line is simple. More likely than not, you’re going to come away empty-handed.

In fact, these two reasons actually reflect three different types of procrastinator. And, needless to say, three different causes of procrastination:

•RUMINATORS who cannot make a decision.

Motivation: Not making a decision absolves them of responsibility for the outcome of events.

•AVOIDERS who are avoiding fear of failure (or, in some cases, fear of success).

Motivation: They are concerned with what others think of them and would rather have others think that they lack effort than ability.

•PERFECTIONISTS who aren’t happy with anything they do unless it’s 100 per cent error-free.

Motivation: They would prefer to do nothing rather than face the prospect of having to measure up to their own exacting standards.

All three types of procrastinator tell whopping great big lies to themselves:

•I’ll feel more like doing this tomorrow. (They don’t!)

•I work best under pressure. (They don’t!)

•This isn’t important. (It is!)

But why?

If we know, deep down, what we’re up to – and ninety-nine times out of a hundred we do – what’s going on? More to the point: what can we DO about it?

In order to answer these questions, we first need to delve into a bit of neuro-anatomy. Don’t worry, it’s perfectly painless.

Let me introduce you to two basic brain structures:

•The amygdala

•The prefrontal cortex (PFC)

The amygdala forms part of what is known as the limbic system – a set of evolutionarily primitive brain structures involved in many of our emotions and motivations. In particular, those emotions – such as fear, anger and pleasure – that are chiefly related to survival.

If you think of your brain as your own personal ‘government’, then the amygdala may be seen as the Ministerial Office of the Department of Emotion. It is the part of the brain where the big and instant decisions are made, such as fight or flight. It is ancient, steeped in evolutionary tradition and wields a heck of a lot of power.

‘Like a colonel then,’ says Andy.

It has the authority to veto ordinary, everyday decision-making processes – to order a Code Red – if it thinks it is in our interests to do so.

Which often it is.

But like any powerful collective, the amygdala is open to corruption and sometimes takes bribes from less pressing and helpful motivations to exert influence over our behaviour.

‘Exactly like a colonel then,’ says Andy.

These are the times when we:

•RUN instead of FIGHT

•DREAM instead of DO

•TURN ON THE TELLY instead of FILING THAT REPORT

The prefrontal cortex, on the other hand, is the official headquarters of the Department of Rational Thought. This is the part of our brain that tells us that we should be working: that we should turn off the telly and start filing that report.

Compared with the amygdala and the limbic system, it is a relative new-build and is responsible for the heightened self-control that separates us from our ancient ancestors and the rest of the animal kingdom. It enables us to:

•plan,

•weigh up different courses of action, and

•refrain from responding to immediate impulses and doing things we’ll probably later regret.

It is the cornerstone of wisdom and willpower.

Now, when we procrastinate, it often feels as if there’s an argument going on inside our heads. An argument between our ‘good’, rational side and our ‘bad’, emotional side. And that’s because there is!

More specifically, this argument is between our logical, conscientious, forward-thinking PFC, and our emotional, hedonistic, heat-of-the-moment amygdala.

‘But why is it that nine times out of ten, the emotion side of the brain always seems to win?’ asks Andy.

It’s a good question. And one directly related to our innate reaction to disturbing or threatening stimuli – the fight or flight response mentioned earlier. Whenever we encounter something we find intimidating – let’s say we open our bathroom door and find a pissed-off king cobra staring straight back up at us – the first thing we do is FREEZE.

Our pulse rate quickens. Our palms start to sweat. And we develop tunnel vision.

We forget all about anything else that we might have been thinking about at the time. The rational decision-making part of our brain, the PFC, shuts down, in other words – while the Department of Emotion (liaising, in this case, with a specially appointed COBRA committee) quickly works out an immediate plan of action:

SHUT THE DOOR!

But it’s not just pissed-off king cobras that set up this temporary no-fly zone over our brain’s decision-making infrastructure.

The same thing happens when we encounter anything that we find threatening: heights, enclosed spaces, the dream girl/guy from accounts, the dream job in accounts—

‘The letter from the Inland Revenue about that job in accounts!’ interjects Andy.

‘I wouldn’t know!’ I shoot back.

We experience what amounts to a low-level dose of anxiety, our amygdalae take over from our PFCs, and we SHUT THE DOOR on whatever it is that is scaring us.

It’ll be gone tomorrow, we tell ourselves.

We’ll feel better tomorrow, we tell ourselves.

Let’s do something else, we tell ourselves.

As mentioned previously, there are a number of reasons why procrastination is bad for us – not least of which is the fact that, as a long-term life-strategy, there is scientific evidence that it’s flawed.

One study, for instance, which looked at college students, showed that on a 4.0 scale, chronic procrastinators achieved a final grade point average of 2.9 whereas those who procrastinated very little averaged 3.6.

But as Andy points out between sparkplugs, not only is procrastination flawed in the LONG RUN, it’s also flawed in the short run.

‘You actually end up experiencing more pain, not to mention more lost opportunities, not doing something than doing it,’ he observes.

Which is true. Research has shown that:

•People who take ages getting into a cold swimming pool in fact experience more physiological discomfort than those who ‘get it over with’ and jump straight in.

•Imagining giving people bad news over the phone is more painful than doing so in real life.

•Deliberation uses up valuable mental resources. In one experiment, for example, women who were forced to make difficult choices between wedding presents to buy for their friends were later found to crack much sooner on a standard lab-based test of willpower (keeping their hands immersed in a bucket of ice-cold water) than women who weren’t exposed to such difficult choices.

But there is one group of people who never put things off.

Psychopaths!

Quite the opposite, in fact.

If psychopaths want something, they go for it immediately – just one of the positives of having an under-strength amygdala. Psychopaths just don’t feel anxiety in the same way as the rest of us. Which means that not only do they not fear failure, but that the rational, logical cockpits of their brains are at less risk of being hijacked and commandeered by the black-and-white extremists of emotion.

Of course, this often leads psychopaths into trouble. With no Minister of Emotion to order a recce or a strategic withdrawal when necessary, they are often guilty of the opposite of procrastination.

Of fighting instead of running.

Of doing instead of dreaming.

But they, needless to say, are the BAD PSYCHOPATHS.

The GOOD PSYCHOPATHS, like Andy, are different.

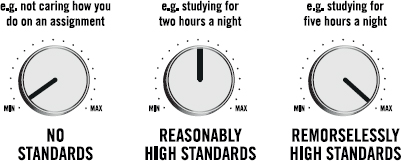

Rather than being stuck and permanently set on max, the Fearlessness dial on the GOOD PSYCHOPATH’S mixing desk is flexible. And can be twiddled up and down depending on the context. And one of the contexts in which it’s shunted up to high is when the chips are down and something needs to be done about it.

So next time you find yourself putting off filing that report or filling in that job application, or asking someone you fancy for the time when you should’ve been asking them out:

•Unchain your inner psychopath.

•Jumpstart your motivation.

•Toughen your resolve.

•THINK about the way you’re thinking, and

•Ask yourself this . . .

SILENCE.

‘Ask yourself what?’ snaps the oil-infested grease-monkey from behind a barrel of God-knows-what.

‘You tell me!’ I say.

‘OK then,’ he says. ‘SINCE WHEN DID I NEED TO FEEL LIKE DOING SOMETHING IN ORDER TO DO IT?’

I have to admit – the monkey’s pretty good!

Then, when you’ve got the answer you’re looking for – YOU DON’T NEED TO WAIT UNTIL YOU FEEL LIKE DOING IT! – turn to the exercises that follow in the next few pages and start putting them into practice. They’ll help you roll your sleeves up and get down to the task at hand.

Talking to Andy about procrastination is like talking to Charlie Manson about a pension plan. He just doesn’t get it.

‘Tomorrow doesn’t exist in Regiment mentality,’ he says, handing me a cup of tea that’s one part Typhoo and nine parts Castrol GTX. ‘Because it’s got a funny old habit of not coming round. If you’ve got something to say, you say it. If you’ve got something to do, you do it.

‘Everyone knows the phrase “Better late than never”. Well, in the Regiment, “late” and “never” can sometimes mean the same. Brew OK?’

I nod through gritted teeth. If the gunk in my cup got washed up in the Channel, Greenpeace would send a flotilla.

And it’s not just on the battlefield that Andy is talking about. The same kind of split-second decision-making that is called for in combat situations crops up time and again in SAS training. One occasion that stands out particularly vividly for Andy was his first ever HALO (High Altitude Low Opening) parachute jump, with full kit.

(Oddly enough, it might well have stuck in my mind too!) Here, in his own words, is how he remembers it:

I sat there in the C130 [Hercules transport aircraft] and checked the altimeter on my wrist: 20,000 feet – nearly four miles above the earth. Only another half mile higher to go before I jumped out the back of this thing – my first time at such height.

There were two four-man patrols and two bundles on this jump. As part of a patrol we had to free-fall together, carrying full equipment loads weighing in excess of 120 pounds. We also had to follow our bundle holding extra gear which was going to do its own free-fall with us, attached to its own parachute.

The oxygen console, which was keeping us alive, ran down the middle of the aircraft. There was a certain amount of gas in our own bottles but we would need that when jumping. So for now we were on the central console instead, linking us up to the aircraft’s main supply.

We were in full kit. Our Bergens were strapped between our legs, ready to hook up behind our arse when we jumped, and our weapons were fastened to the left-hand side of the parachute, which was already attached to our backs. The helmets and their oxygen mask tubes running to the console looked like something out of Star Wars.

This was a big test for us as we were all on the Military Free-fall Course and didn’t want to fail this jump. The idea behind it was to get men and kit all landing in the right place at the right time so whatever mission they had to carry out, they had the gear and the manpower to do it.

So far, I wasn’t feeling worried. All the things that we were about to do, like getting on to the oxygen, were drills that we had been taught and practised. Without oxygen we wouldn’t be able to breathe – and by the time you hit 22,000 feet there isn’t enough of the stuff around to keep you alive.

Everybody was mentally and physically dry-drilling: simulating pulling their handle that would deploy their main canopy and then looking above them to see a big bag of washing billowing out. Just in case the clothes line wasn’t there, they were also going through Plan B: pulling the emergency cut-away of their main canopy and deploying the reserve.

I couldn’t see the point of dry-drilling just minutes before jumping. Whenever we ‘jumped kit’ or jumped at night we would have an AOD [automatic opening device] attached to the parachute. This worked by barometric pressure. At 3,000 feet it automatically kicked in so if you got into a spin, had a mid-air collision, knocked yourself out or broke your pulling arm, it at least got the canopy out of its bag.

There were horrendous stories of people going into spins, especially with heavy kit. If the kit isn’t packed right or balanced right then as soon as you jump and the wind hits it, it does its own thing. And then you’re really in the shit – because it keeps doing its own thing, only faster and faster.

I could tell there were a couple of lads who were flapping. Either that or they wanted to show the instructors they knew the drills. They were giving it the old thumbs-up like something out of Top Gun. They might as well have thrown in a few salutes for good measure.

I was going to jump, there were no problems with that. But I just didn’t want to cock it up. I didn’t want to be the one who didn’t land next to the bundle.

One of the things about barometric pressure is that the less there is of it, the more gases will expand. All of us were farting big time but thankfully due to the oxygen we couldn’t smell anything!

I eventually joined in the dry drills and kept the instructors happy by showing them I was putting their teaching into practice. But to be honest, if I didn’t know the drills by now, I never would.

It wasn’t long before there was a loud electrical winding sound as the ramp at the rear of the C130 started to come down and daylight burst in making us squint. It was like God had started shouting at us. I wasn’t really thinking all that much about anything now. I was just going through the rigging-up drills as I’d been taught. I had no control over anyone else and certainly not over the bundle. Nothing else mattered. All I was going to do was jump and try really fucking hard to land within spitting distance of the kit.

I checked the altimeter on my arm – 22,000 feet – as we got the command to rig our kit up. All the commands were printed on large flash cards because of the noise and the oxygen masks. I pushed the Bergen behind me and attached it by hooks to my rigs harness. We were now waiting for the command to go up towards the tailgate. When it came we unhooked the oxygen from the main console and attached it to our own bottles.

A couple of the lads gave some more Top Gun thumbs-ups. All I wanted to do now was just get out of the aircraft. The combined weight of the equipment and rig together was well over 200 pounds.

On the command, our patrol moved to the ramp like a line of ducks, waddling from foot to foot, weighed down by all the gear. I was on the left-hand side of the bundle, another lad was on the right and a third bloke was at the rear. It looked like a thick, two-metre-long bullet with a rig strapped on it.

We pushed it on its trolley wheels towards the tailgate with the wind blowing against us as it lapped on to the ramp area. About six inches from the edge of the tailgate there were two chocks that stopped it toppling over into space. The aircraft started doing corrections, jockeying us around as we semi-stooped over the bundle, holding it in position.

I checked my altimeter: just under 25,000 feet.

I didn’t even bother looking out at the blue sky and clouds which were now way below us. Why bother? It wasn’t going to get me off the ramp any quicker or help me keep up with the bundle.

The fourth member of the patrol had his toes on the edge of the ramp. Everybody was bunched up over the bundle, really close to each other, because we all had to get out at the same time to keep with the thing.

We were waiting for the two-minute warning which would signal that we were on the run-in. Even through goggles it was clear to me that everybody was tensed up on the ramp.

I couldn’t understand why.

Everyone wanted to do the jump. Everyone wanted to pass this part of the training. We’d all been trained up to the eyeballs. So what was the problem? It seemed to me that the time to worry was if you fucked up or had a malfunction in mid-air which you couldn’t get out of.

All of a sudden the RAF loadmaster, who was also on the ramp holding the paracord that was keeping the chocks in position, held up two fingers and everybody started banging the next man doing the same.

‘Two minutes!’

I’m not sure we heard each other through our oxygen masks and above the deafening roar of the wind and the aircraft engines. But that didn’t matter. It was part of the drill to make sure that anyone flapping big style knew it was nearly time to jump.

All eyes were now fixed on the unlit red and green lights either side of the ramp. More banging and shouting.

‘Red On!’

Then, as the green light came on and the loadmaster pulled the chocks away:

‘Ready!’

We gripped the bundle as high as possible for a clean exit.

‘Set!’

Now we rocked back ready to push it out.

‘Go!’

We piled over the ramp, all four of us trying to keep hold of the bundle and drop with it for as long as we could before the jet stream ripped us away from it.

I still didn’t bother looking at the ground. It was a full three minutes away yet and I wanted to use every second of that time to keep up with the bundle.

Basically, because of all the equipment you’ve got on, you can’t move about the sky that well. It’s as if your whole body is an arm shoved out a car window at 120mph. You fall – and fight as hard as you can to keep yourself stable, stay in a group and get down to the bundle that now seems miles below while all the time your Bergen is catching air and trying to shunt you into positions you don’t want to be in.

I watched the bundle’s AOD deploy its canopy below me and started to look about at the ground. There was total silence. It felt as if I was suspended in the sky. But before I knew it the earth was rushing up to meet me and I hit with both feet, landing about five metres from the bundle.

And that was it. Not much to think about apart from the fact that I’d passed the test.

Then it was straight on to a vehicle for the half-hour drive back to the airfield and the waiting C130 for another go.

Practical Tips for Getting It Done, Getting It Over With, and Getting It Not Quite Right . . .

Andy once gave me a bit of advice about parachute jumping. I did one in Australia several years ago and texted him the night before.

‘Keep your eyes open and your arse shut!’ came the reply. ‘And make sure you get it the right way round!’

Fortunately, I didn’t have to make any decisions that day. The guy I was strapped to made them all for me. But if it had been down to me, who knows?

‘I do,’ says Andy. ‘You geeks are so full of hot air you’d have probably gone up.’

‘Which is why we can walk on water,’ I retort.

But for those of you out there not as well endowed in the helium department as I am, and not as well endowed in the psychopath department as Andy, here are some tips that will help you take the plunge. That will lure you out on to the nerve-shattering tailgate of life – then off into the rush of terminal velocity decision-making!

‘We used to have a saying in the Regiment,’ Andy says, taking off his boiler suit and binning it for the day. ‘Leave till tomorrow only the stuff that you’re prepared never to do.’

A sentiment echoed by the racing driver James Hunt in the film Rush: ‘The closer you are to death, the more alive you feel,’ he observed. ‘It’s a wonderful way to live.’

If you procrastinate you will actively seek out distractions, particularly ones that don’t take a lot of commitment on your part (this, incidentally, is why email was invented). Distraction serves as a method of emotional self-regulation. It’s a diversionary tactic to keep your fear of failure under control.

To counteract this, start planning what you do – and then close your eyes and VISUALIZE yourself doing it. The more specific, detailed and graphic your visualization the better. Picture yourself carrying out the task, and executing it successfully – avoiding interruptions and focusing on the job at hand.

This is just one of the methods used by members of the SAS’s Counter-Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) team when training for hostage rescue scenarios.

‘Before storming the Killing Housefn2 we would go through in our heads the precise drill for engaging the enemy and getting the hostages to safety,’ says Andy. ‘Lobbing in a flash-bang, a stun grenade . . . quick scan of the room . . . short burst – tap-tap – of machine-gun fire if necessary . . . room clear, move on.’

And with good reason. Research shows that when we imagine doing something – say, playing tennis, for instance – the exact same areas light up in the sensorimotor region of our brain as if we were doing it for real.

Especially important when you practise with live ammunition!

While you picture yourself performing the task, try to access precisely what it is about it that you don’t like, exactly what it is that makes you reluctant to attempt it in the first place. Forewarned is forearmed.

And once you start putting your finger on what lies behind your avoidance behaviour – be it practical, workable problems or irrational, illogical fears – you can begin to work through it.

Because of their dictatorial amygdalae, procrastinators tend to fold in the face of immediate challenges, opting for short-term pleasure over long-term gain instead. So next time you find yourself putting off something important, put off putting it off for a moment, stick your feet up in a quiet corner, and ask yourself this:

Is how BAD I’m going to feel when I have to rush this task under pressure going to be anything like how GREAT I’ll feel when I’ve got it under my belt in good time?

As Andy memorably put it when we first started writing this book together: ‘This time next year we’re going to be glad we started TODAY.’

Work, to a procrastinator, is a bit like Pringles to the rest of us. They take ages to open the packet. Then once they pop, they just can’t stop! Which is why, of course, they dread getting started in the first place.

To get around this energy-sapping vicious circle, here’s what you do.

Set a predetermined period of time in advance – say, an hour – during which you make a contract with yourself to work on whatever it is you need to get done. And then RING-FENCE it. This means closing the door and putting up the ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign, turning off your phone, email, Facebook . . . anything that isn’t DIRECTLY RELEVANT TO WHAT YOU ARE DOING RIGHT NOW. And then lifting the curfew once the 60 minutes is up. And make sure you lift it on time!

Not after 59 minutes.

Or 61 minutes.

But after one hour DEAD.

Transform your attentional spotlight from a strip light into a laser beam.

When it comes to work, a procrastinator is like a prize fighter waiting to land the one big knockout punch – except it never materializes, and by the time the awful truth dawns, the fight is over, and they’ve lost on points to an opponent who has thrown more leather.

Procrastinators wait for large, unbroken, marble-smooth slabs of time upon which to get started instead of rolling their sleeves up and making do with more temporary, makeshift, rough-and-ready surfaces.

So now you know, don’t hang around for the perfect opportunity to present itself any longer. Don’t keep saving up for huge, uninterrupted wads of time. Instead, start getting rid of some of that loose, opportunistic change that’s been rattling around for ages deep in the lining of your brain.

Andy once told me that he hammered out large chunks of his books not in some big comfy armchair at home or some sun-dappled villa on the Algarve, but on the West Coast Mainline and in the food courts of motorway service stations.

‘I spend a lot of time on the move,’ he said, ‘and you just have to work when you can. But there’s something – I don’t know – a little bit sneaky about working on the train or in a cafe. It’s like you’re nicking time off yourself.’

The glamour!

AND FINALLY . . . A WORD ON PROCRASTINATION AND PERFECTIONISM.

As mentioned earlier, procrastination and perfectionism often go hand in hand. Knowing the effort required to live up to their own unrelentingly high standards, a procrastinator is beaten before they even start – remember the concept of ‘learned helplessness’ in the previous chapter? – and so prefers not to try in the first place.

In fact, research suggests that procrastinators are frequently self-handicappers. Rather than risk the prospect of not being up to the challenge, their deep-seated lack of confidence combined with a Walter Mitty-like fantasy of unrivalled, heroic success fiendishly join forces to render legitimate success impossible.

To the procrastinator, being seen to lack ABILITY is the worst-case scenario. Better, instead, to be seen to lack OPPORTUNITY.

Even if they do eventually manage to get down to a task, the perfectionist-procrastinator endeavours to make things difficult for themselves. They spend so much time trying to get it ‘right’ that other, more important tasks suffer as a result. And a vicious cycle sets in.

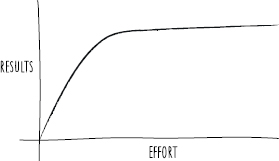

They seem completely unmoved by the Law of Diminishing Returns – that, for any given task, the continuing application of effort steadily declines in effectiveness after a certain standard has been reached – and plough on regardless.

Ask yourself this!

If it takes 20 minutes to do something to 70 per cent (that’s a return of 3.5 per cent per minute), is it really worth spending another 40 minutes (on a return of 0.75 per cent per minute) to get it 100 per cent?

LAW OF DIMINISHING RETURNS

Unless the project is a matter of life and death, most people answer NO. In fact, when you put it like this, even perfectionist-procrastinators answer no.

But it’s easier SAID than DONE.

THINKING it isn’t the same as FEELING it – and when perfectionist-procrastinators are engaged on a task, the emotion area of their brains, their amygdalae, keep their noses to the grindstone until they’re finally convinced they can’t do it any better.

Ring any bells?

If it does, here’s something you can do about it:

You can relax your FUNDAMENTALIST black-and-white standards and start thinking more MODERATELY in graduated shades of grey.

Let’s imagine, for example, that you are a student, and a perfectionist when it comes to your academic work. You will probably be having the following internal dialogue with yourself on a daily, if not hourly, basis:

‘Unless I get distinctions in my assignments then I am worthless.’

This dialogue is a THOUGHT BULLY that is pushing you around and getting you to run errands for it which you don’t want to run.

So, what’s the solution?

Well, it’s the same as for any bully.

You STAND UP TO THEM!

Overcoming your perfectionism involves coming to terms with the fact that, although the standards INSIDE YOUR HEAD may appear in black and white, those OUTSIDE it, in EVERYDAY LIFE, in general do not.

They fall on a spectrum of grey.

So instead of studying for five hours a night, you may want to cut it down to two hours a night, and throw in some relaxation time instead.

In other words, for whatever kind of perfectionism you may be harbouring, you need to:

1.Identify the BULLY – ‘I need to get a distinction in all my assignments.’

2.Engage in the appropriate SELF-TALK – ‘I know that if I stand up to the bully and down tools after a couple of hours I will feel anxious in the short term but better in the long term.’

3.Take the appropriate ACTION – down tools after a couple of hours, invite a friend round for dinner, and raise a glass to the benefits of not studying for five hours a night.

4.Do this REPEATEDLY, braving the anxiety of your newfound freedom and resisting the temptation to go back to your old five-hour-a-night habit.

Until: PRACTICE MAKES NOT PERFECT!

But that’s not all.

You can also . . . ask yourself this: WHAT’S THE WORST THAT CAN HAPPEN ANYWAY?

You see, most of the time our fears are completely unfounded. As mentioned earlier, we have a spectacular capacity for imagining things to be far worse than they really are. And guess what? This is just as true for failure as it is for anything else.

When cognitive behavioural therapists talk about procrastination, they often talk about the importance of ‘putting down the whip’. Of:

•Permitting ourselves the luxury of making mistakes.

•Not beating ourselves up when we make them, and

•Not allowing the concept of PERFECTION to become tangled up in our concept of OURSELVES (‘If I’m not PERFECT I’m NOBODY’).

Well, Andy and I go one better than that. We recommend that every now and again you don’t just make the odd mistake here and there. That would be too easy. No, instead we recommend that you actually set out with failure as your goal.

Why?

Because once you start doing it, succeeding to fail becomes harder and harder to achieve.

I remember a BAD PSYCHOPATH I spoke to in a maximum security unit once telling me about a game he and his mates used to play when they were younger and out on the town. They used to have competitions to see who could get the most rejections from girls in bars. The incentive was pretty big. Whoever it was would have all their drinks taken care of the next time they went out.

Not bad!

But guess what started happening? The more they got used to rejection, the more they realized that – in the grand scheme of things – getting the elbow actually meant bugger all, the harder it became to pull off.

And the easier it got to go home with a girl on their arm!

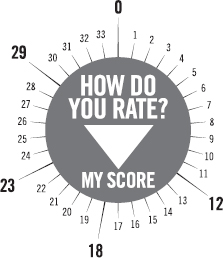

0–11 Procrastination is significantly reducing your quality of life. Get it sorted! Now!

12–17 You already have suspicions about yourself – but hey, you’ll deal with those later.

18–22 Room for improvement – but you can probably cut it off.

23–28 You have the odd lapse every now and again but generally get things done.

29–33 You are disciplined and organized and usually do things when you need to.

![]() Keep a note of your scores for each questionnaire because at the end of the book we’ll be inviting you to take part in a unique nationwide survey which will enable you to find out where you sit on the overall GOOD PSYCHOPATH spectrum.

Keep a note of your scores for each questionnaire because at the end of the book we’ll be inviting you to take part in a unique nationwide survey which will enable you to find out where you sit on the overall GOOD PSYCHOPATH spectrum.

fn1 A little test will appear at the end of the next six chapters, each of which provides a general assessment of the particular personality characteristic under discussion. To find out how you measure up on each of the Seven Deadly Wins, just fill out the respective questionnaire and check your score against the scale provided.

fn2 A building on the SAS barracks in Hereford which serves as a mock-up for terrorist situations.