The failure of the Deer Creek Tunnel meant Cincinnati’s rail entanglement devolved in the nineteenth century’s closing decades into the worst such situation in the United States. Then, with the appearance of nearly a dozen new electric interurban railroads between 1900 and 1907—all of them forced to terminate miles from the city center or travel over the tracks of the Cincinnati Street Railway—the situation grew even worse.

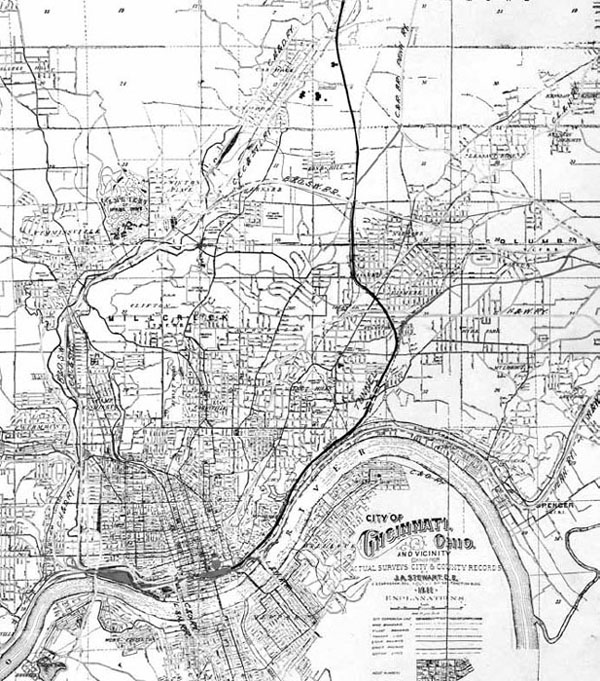

Intelligent men recognized that a solution to the new and overlapping problem created by the interurbans could play a much more lucrative role as part of a riverfront union station. Borrowing from the business plan of the defunct Cincinnati & Dayton and its unfinished Deer Creek Tunnel, a six-mile line between Norwood and the basin via Walnut Hills or O’Bryonville would create a high-speed entrance for electric interurban railroads and a superior approach for existing steam passenger trains. Either route would inevitably necessitate a tunnel, but one just a quarter the size of the abandoned Deer Creek Tunnel.

The first man to act on this opportunity was Jacob Schmidlapp, a prominent figure in Cincinnati’s business community who built his fortune in tobacco and whiskey wholesaling, warehousing and real estate development before chartering the Union Savings Bank & Trust Company. After his wife and daughter died in a train wreck outside Kansas City in 1900, he spent the remainder of his life giving his money away, with an emphasis on improving the housing conditions of Cincinnati’s poor.

This circa-1935 aerial view of the West End illustrates the hellish overcrowding of Cincinnati’s basin; for much of the nineteenth century, it was the most densely populated area in the United States outside New York City. Central Parkway and the subway are visible in the top-right corner of this photograph. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Portrait of Jacob Schmidlapp. Courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

Schmidlapp knew that an interurban-only approach would not repay its construction cost, and although a riverfront union station promised boundless profits for the exact same six-mile railroad, such a station was not a certainty. However, he believed that interurban railroads offered a solution for Cincinnati’s greatest social problem—overcrowding of basin tenements—and argued that a rapid commuter service on the interurban entrance he proposed would enable new middle-class suburbs in Norwood and beyond. The vacancies left in the basin’s old row buildings would allow the poor to occupy larger spaces in existing buildings and excess buildings could be demolished for park space. He hired his own surveyor, spent years promoting his plan and even offered to invest an unspecified amount of his own money.

The business community and the city, for reasons that are not entirely clear, did not align themselves with his plan. After the Union Depot & Terminal Company’s plan was announced in 1910, Schmidlapp made a point of reminding all that he devised and promoted a similar plan to their “Supplemental Tunnel Route” nearly a decade earlier. The existence of such a railroad by 1910 would have simplified the planning of a riverfront union station and earned tremendous rental fees for whichever individual, company or municipality happened to own it.

The only interurban railroad that made public extravagant entrance plans on its own accord was the Ohio Electric Company, which consolidated a vast network of interurban lines throughout the Midwest under its name in 1907. It studied basin entrances for both of its Cincinnati-area lines, each terminating on Chicago-style elevated viaducts above Cincinnati’s downtown streets. Its Springfield Pike, or “Mill Creek Valley Line,” was planned to approach the city along a Norwood route similar to Schmidlapp’s railroad and the later Supplemental Tunnel Route. Its College Hill approach proposal was the more interesting of the two, involving a tunnel under Clifton and another in Walnut Hills.

Tunnels beneath the O’Bryonville business district were planned as part of the the Supplemental Tunnel Route and Rapid Transit Loop. Courtesy of the author.

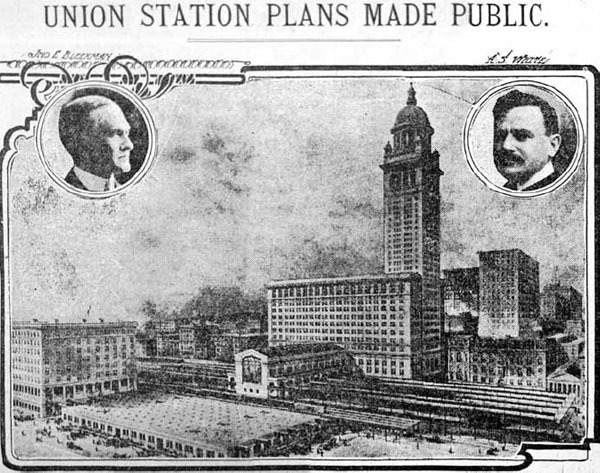

In 1910, fifteen years before the region’s railroads chose a West End site and built Cincinnati’s spectacular Union Terminal, the city granted a franchise for an even more ambitious union station plan on the city’s riverfront. The Union Depot & Terminal Company, headed by New York financier John Bleekman and backed by J.P. Morgan, worked to construct a huge elevated station where all intercity passenger trains and electric interurbans would converge within walking distance of Fountain Square.

Adjusted for inflation, its estimated $36 million cost dwarfed the eventual $44 million cost of Union Terminal, and the Union Depot & Terminal Company sought to recoup construction costs and eventually realize a profit with a variety of side businesses. A five-hundred-foot office tower above the station head house and acres of warehouse space beneath its elevated station tracks promised steady income, but a critical part of the plan, known as the Supplemental Tunnel Route, revisited Schmidlapp’s earlier interurban entrance plan.

This promotional graphic appeared in various local newspapers in 1910. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Times-Star.

The original $6 million Supplemental Tunnel Route plan featured two four-track tunnels: one under Owl’s Nest Park and Madison Road in O’Bryonville and another under Mount Adams. In later proposals, this tunnel was eliminated in favor of a longer surface route around the south base of the hill. Changes such as this, and those in Norwood and O’Bryonville, might have been orchestrated to mislead land speculators, and all along, the Union Depot & Terminal Company might have in fact planned to use Schmidlapp’s route.

The Union Depot & Terminal was planned for the land presently occupied by Fort Washington Way. Courtesy of the 1910 Report of the Union Depot & Terminal Company.

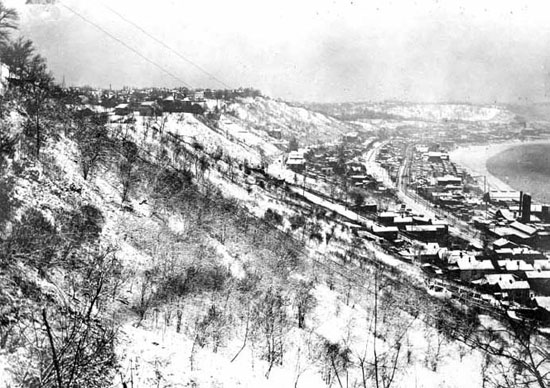

A circa 1905 view of the East End from Eden Park. The Supplemental Tunnel Route was to have hugged the hillside above the Little Miami Railroad and turned north at Torrence Ravine, visible at top center. Later, the Rapid Transit Loop’s eastern routing was planned to follow the same path. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

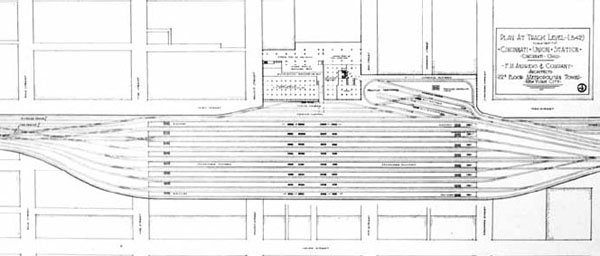

The Supplemental Tunnel Route and its relationship with area railroads. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Union Depot & Terminal Company.

The chronological overlap of the Union Depot & Terminal Company’s 1910 and 1912 franchises, the 1911 canal lease and the Arnold Report of 1912 indicate that, for several years, an epic battle involving the railroads and Cincinnati’s prominent citizens raged behind the scenes. The Union Depot & Terminal Company’s own publications, including its 1912 report, made explicit mention of the unavailability of the Miami–Erie Canal, despite the state having recently granted a lease for railroad purposes. Meanwhile, the contemporaneous Arnold Report avoided consideration of the Union Depot & Terminal Company plan, other than a casual mention of the Supplemental Tunnel Route, but called “The Bleekman Plan.”

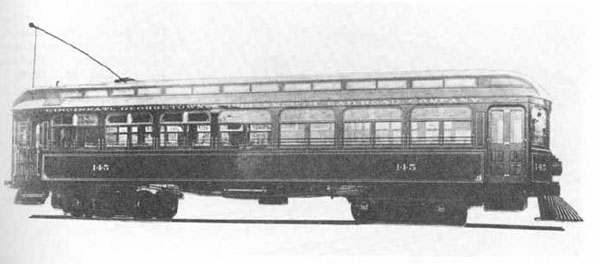

Typical interurban car. Courtesy of the Noel Prowles Collection.

This schematic illustrates one interurban terminal plan made public by the Union Depot & Terminal Company. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Union Depot & Terminal Company.

To fill the company’s financing gap, mention of public financing was periodically voiced. But instead of financing the station itself, it appears that forces acting on behalf of the City of Cincinnati hatched the Rapid Transit Loop plan—which was advertised as a combined interurban entrance and rapid transit railway—to place both remaining practical railroad entrances under city control. Track rental from the two approaches was of keen interest to the era’s corrupt Republican political machine; like the annual rental generated by the Cincinnati Southern Railroad, such income beyond the state-limited 10-mill property tax, street railway franchise payments and typical fees and fines could fuel the machine’s patronage.