The interurban entrance schemes proposed in the new century’s first decade by Jacob Schmidlapp, the Ohio Electric Company and the Union Depot & Terminal Company largely ignored the Miami–Erie Canal, whose eventual availability for use by any type of railroad was uncertain. They knew that any mention of constructing a railroad in place of the obsolete canal could turn public sentiment against the remainder of any proposal—a result of the disastrous logistical and legal conditions created by the laying of railroad tracks in the center of Eggleston Avenue.

Originally a series of locks connecting the canal’s turnaround pool with the Ohio River, Eggleston Avenue was, by the time the Rapid Transit Loop was conceived, a mess of railroad tracks on state property over which the City of Cincinnati collected no revenue and exerted no control. Rail activity on this short spur blocked pedestrian, horse and streetcar traffic between downtown, Mount Adams and the East End, and the lease of the remainder of the canal within city limits under similarly loose terms promised the spread of this situation to the city’s most densely populated sections.

This strange arrangement arose due to a sequence of events described in 1913 by George Barch, President for the Association for the Improvement of the Canal:

In 1863 the Ohio Legislature passed an act granting the canal bed between Broadway and the river to the city of Cincinnati for highway purposes… Afterwards the Little Miami Railway, by consent of the city, constructed a steam railroad track on that part of Eggleston avenue that had formerly been the canal bed. The result was that the Supreme Court of Ohio decided that Eggleston Avenue as was within the limits of the old canal was therefore forfeited to the state of Ohio by reason of violation of the terms of the grant in allowing the railroad company to use the ground for railroad purposes, even though the city of Cincinnati had spent nearly a million dollars in filling and paving the entire avenue, with our filling and paving, belongs to the stat of Ohio which rents it to the Pennsylvania Railroad.

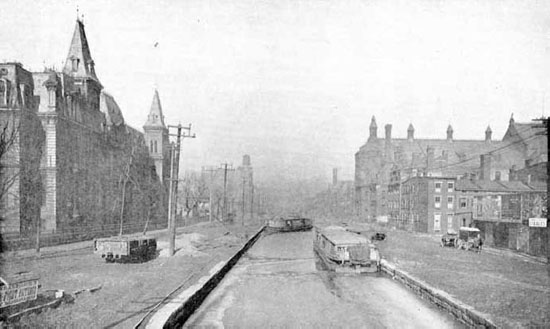

The Miami–Erie Canal, looking north from the Twelfth Street Bridge circa 1900. The City Hospital is visible at left. Courtesy of George Kessler’s 1907 A Park System for Cincinnati, OH.

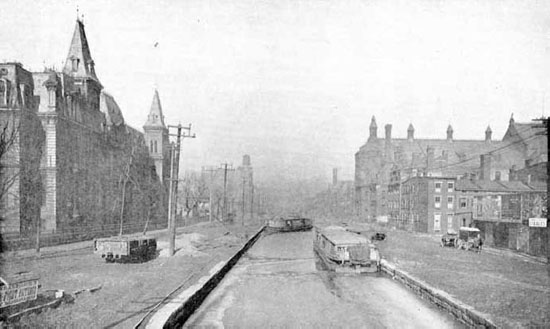

View of Eggleston Avenue, left, and Interstate 471. The tracks of the Little Miami Railroad replaced the canal’s Ohio River locks in the center of Eggleston Avenue. Courtesy of the author.

With this history, it is easy to understand city opposition to an exotic 1883 request by the Cincinnati Northern Railroad to construct a steel viaduct directly over several miles of the canal. The City of Cincinnati had no jurisdiction over the canal or parcels of land to either side (legally defined as “canal lands”) but was able to stop the plan by denying Cincinnati Northern’s request to construct an extension of its canal viaduct over city streets en route to an elevated terminal station at Government Square.

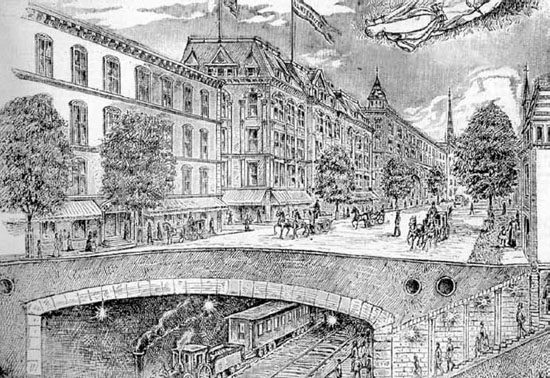

Drawings of the canal replaced by a Parisian boulevard and underground railroad first appeared in the 1880s. Courtesy of the Graphic.

At that early date, Cincinnatians made it known that any redevelopment of the remainder of the Miami–Erie Canal must ensure a favorable aesthetic outcome; sketches of an underground railroad capped by a Parisian boulevard first appeared in local publications soon thereafter. Such a tunnel was impractical in the steam era, but after construction of the country’s first electric rapid transit subway in New York City and electrification of Grand Central Station, Cincinnatians were at last willing to consider the canal’s redevelopment.

Meanwhile, there were from the 1850s onward continuous calls for expansion of Ohio’s two cross-state canals. Miami–Erie Canal expansion schemes were typically paired with proposals for construction of an artificial Ohio River harbor where the Queensgate railroad yard is now located. The harbor facility would have been created by a lock and dam near the mouth of the Mill Creek and would have connected with the widened and deepened Miami–Erie Canal near the present location of today’s Interstate 75/74 interchange. Later plans would have used a dammed and straightened Mill Creek in place of the canal north of St. Bernard. Aside from providing an area safe from river currents for the transfer of cargo, the harbor would also have created a refuge for towboats and barges from winter ice flows. Proposals for barge and ship canals continued into the 1950s and 1960s, but by then involved canalization of the Great Miami River.

View of the canal looking west from Elm Street toward the elbow. The powerhouse visible at center used canal water until early 1920, delaying work on Section Two. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

This spillway, built in 1922 north of St. Bernard, diverted canal water into the Mill Creek. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Convinced that its contemplated cross-state canal expansion project, if built, would inevitably utilize the Mill Creek through Cincinnati, in 1911, the Ohio state legislature passed Senate Bill no. 259, permitting the City of Cincinnati to lease the canal for $32,000 annually between its downtown terminus and the city’s northern corporation line just north of Mitchell Avenue. Construction of a railroad tunnel beneath the boulevard was an optional condition of the lease, but if built, its use by steam locomotives was prohibited except in case of “emergencies.” A revision to the lease permitted the construction of vents in the subway’s roof, ostensibly to mitigate the “piston-action” of air pushed ahead of speeding electric subway trains. However, these vents were in fact built in order to permit the regular operation of steam locomotives in the canal subway. What specific role the tunnel would eventually play in the city’s passenger and freight railroad network was not determined prior to or even during subway construction. In 1922, while the subway was being built, Popular Mechanics reported, “In order to admit freight cars, if necessary, the tubes have been built with a clearance of 14 feet 9 inches over the top of the rail.”

If it had been the intention of state politicians to prevent the tunnel’s eventual usage by mainline passenger and freight trains pulled by steam locomotives, they could have mandated a low tunnel ceiling that would have prevented the use of standard equipment. This detail is a critical part of the subway’s story: standard subway trains are shorter than standard box cars, and the twelve foot, six inch “Assumed Car for the Belt Line” detailed in the 1914 Edwards–Baldwin Report would have enjoyed over two feet of vertical clearance. But beginning in the late 1920s, those forces acting to kill the subway rewrote its history and convinced the public that the tunnel was unusable due to its incompatibility with a variety of equipment. The nature of the irresolvable problem shifted depending on whom was describing it, but usually subway foes claimed that the tunnel dimensions were “too small” and trains “couldn’t make the curves.”