The Union Depot & Terminal Company attempted to fulfill the conditions of its franchise by staging a groundbreaking in December 1912. The event appears to have been limited to a brief shovel ceremony and the moving of a house near the intersection of Kilgour and Pearl Streets. The shifting of this house to an adjacent vacant lot was not successfully defended in court, and the company’s franchise was forfeited on January 1, 1913.

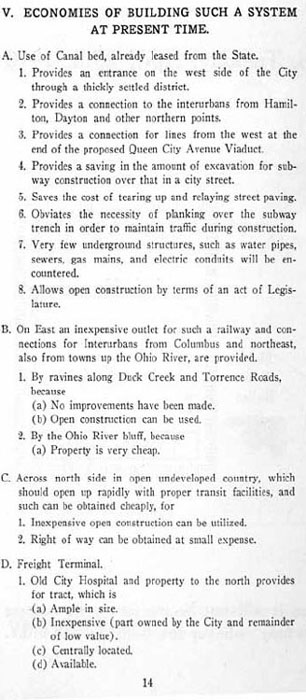

The effort to kill the riverfront union station was helped immeasurably by the March 1913 flood, which threw railroad finances into disarray. With the Union Depot & Terminal Company forced to negotiate a new franchise with the city and its tentative financiers attending to flood damage, planning for Arnold’s beltline progressed rapidly. House Bill no. 562, passed April 18, 1913, revised the canal lease, which extended it to include the canal through the neighboring city of St. Bernard and required subway construction to Dixmyth Avenue. How and why Dixmyth Avenue—now Martin Luther King Drive—was determined to be the northern extent of required subway construction is unclear. The Arnold Report saw no functional need for a subway north of Queen City Avenue, and it even calculated the reduced expense of a subway only as far north as Liberty Street. It’s possible that this condition was motivated by those who sought to prevent Brighton and Camp Washington from potentially evolving into a freight yard.

Construction of Arnold’s beltline for the exclusive use of interurbans could not be economically justified. Implementation of a rapid transit service on the beltway, however, promised enormous ridership. In December 1914, a new city-funded report, “Report On Plans and an Estimate of the Cost of a Rapid Transit Railway and an Interurban Railway Terminal for the City of Cincinnati, Ohio,” but better known as the Edwards-Baldwin Report, refined and improved upon the recommendations of the Arnold Report by detailing the route, stations and electrical system of what was now termed the Rapid Transit Loop.

The Edwards–Baldwin Report discarded a number of Arnold’s extravagances. It reduced the canal subway from four tracks to two and eliminated a third track at stations that would have permitted express service. It ignored the Cincinnati and Westwood Railroad and made no mention of the viaduct that would have connected it with the canal subway. A spur from the belt line to form connections with Clermont County interurbans near the present site of Lunken Airport was also snipped. There was no follow-up to Arnold’s Plan no. 5 and its mile-long tunnel to Hyde Park.

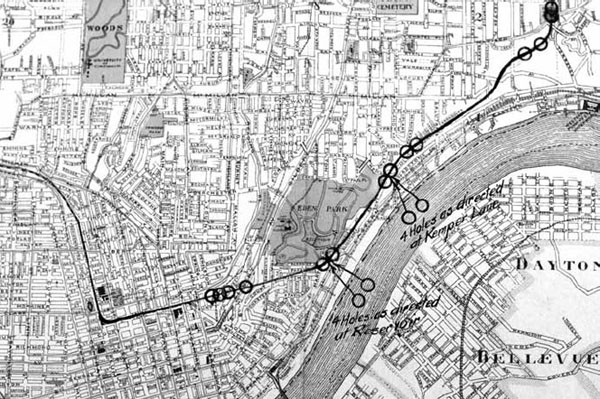

This map of test borings made in 1915 indicates that the Mount Adams tunnel was still under consideration. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

Conceptual subway station design for Walnut Street. Courtesy of the Edwards–Baldwin Report.

A pamphlet clipping comparison with other cities. Courtesy of the Interurban Rapid Transit Bond Issue Campaign Committee.

Its two sections and two authors also neatly divided the eventual capital obligations of the loop’s lessor and lessee. The first half of the report, written by assistant city engineer F.B.Edwards, summarized speculative routes and stations, with the capital costs to be incurred by the city. Ward Baldwin, a member of Boston’s Rapid Transit Commission, wrote the report’s second half, which discussed the character and cost of rolling stock and electrical systems, with the capital costs becoming the responsibility of the Cincinnati Street Railway.

A pamphlet clipping. Courtesy of the Interurban Rapid Transit Bond Issue Campaign Committee.

The railway described by Edwards formed the basis for what was actually built. He prescribed a minimum track radius of 1,000 feet outside the downtown area, and all curves would be super-elevated up to 6 inches, allowing speeds of forty-five miles per hour to be maintained. Grades would be limited to 2 percent, except for several steeper climbs of less than 500 feet. Stations would be built with 240-foot platforms, expandable to 400 feet. Platforms were to be built 4 feet above track level, and surface and elevated stations were to have a roof “of wood supported on steel framework,” similar to the canopies of many elevated stations in New York City. All stations were to have “toilet rooms for men and women.”

Edwards’s figures were all based on the seventy-foot cars of the Cambridge–Dorchester subway (today’s Red Line) in Boston, which began operations in 1912. These cars could achieve speeds of forty-five miles per hour on a 2 percent upgrade and fifty-five miles per hour or more on level track. Whereas these cars operated in four-car trains in Boston, Cincinnati’s platforms would be built long enough for trains of three cars. Most often they would operate as two-car trains.

The design of the Rapid Transit Loop as outlined in the Edwards–Baldwin Report was based on the specifications of Boston’s Cambridge–Dorchester Subway, which began operation in 1912. Courtesy of the author.

A maintenance and storage yard was planned for farmland north of St. Bernard, approximately where the interchange of I-75 and the Norwood Lateral is presently located. This location allowed an interchange with the steam railroads that would tow the rapid transit cars from their place of production to Cincinnati. Edwards called for sufficient storage space for 160 rapid transit cars, an inspection shed, a repair shop, a paint shop and “trainmen’s and yardmen’s lobbies.” The cost estimates of the Edwards–Baldwin Report assumed an initial purchase of between seventy-two and eighty individual cars, about half of the system’s maximum capacity.

Whereas the Arnold Report focused on interurban railroads and mentioned city-operated rapid transit service as a future possibility, the Edwards–Baldwin Report focused on the specific character and potential of a city-operated rapid transit service operating on tracks mixed with interurban traffic. It gave detailed descriptions of each of the beltway stations—a matter Arnold’s otherwise intensely detailed report did not address.

Many changes to the belt line outlined by Edwards in 1914 were made when final blueprints were made in 1919. Subway and surface routing in the canal right of way did not change, but two stations shifted position and a Mitchell Avenue station was eliminated. In 1914, a surface station planned opposite Crawford Avenue in Northside was shifted to Clifton Avenue, and a subway station at Hopple Street was replaced by a surface station at Marshall Avenue. This second change appears to have been caused as much by cutbacks as by the complicated legal and financial relationship of the Rapid Transit Loop and Central Parkway. It was not known in 1919 if Central Parkway would be built north of Brighton, meaning construction of a subway station at Hopple Street might be an unneeded expense.

In Bond Hill, the Rapid Transit Loop was built in the mid-1920s nearly a half mile north of the alignment planned in 1914. As such, a planned station at Paddock Road was shifted to Reading Road (but never built). Station locations at Montgomery Road and Forest Avenue were retained in their original locations, but the loop itself was rerouted to terminate at Madison Avenue in Oakley.

Three stations on the never-built eastern half of the Rapid Transit Loop were described in the Edwards–Baldwin Report as follows:

Oakley Station, 5.21 miles going east from Canal Station, is in a subway on private land on the east side of Duck Creek opposite Smith Road. Entrances and exits are at Dacey Avenue.

Dana Station, 4.5 miles going east from Canal Station, is in the open on private land to the east of Duck Creek and between the N. & W. R. R. and Vista Avenue. The City has considered the building of a viaduct over Duck Creek Valley on the line of Delta Avenue. Should this viaduct be built this station could, without making alteration, be connected with it.

Madison Station, 3.39 miles going east from Canal Station, is on private land to the south of Madison Road. It is partly covered and partly in the open, with entrances and exits at Madison Road.

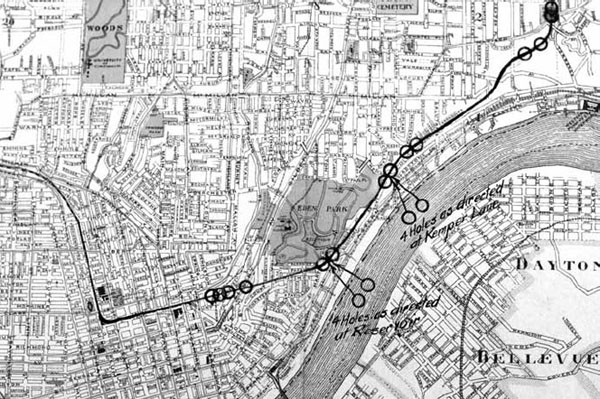

Conceptual plans for the concrete trestle stretching between Mount Adams and Torrence Avenue. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

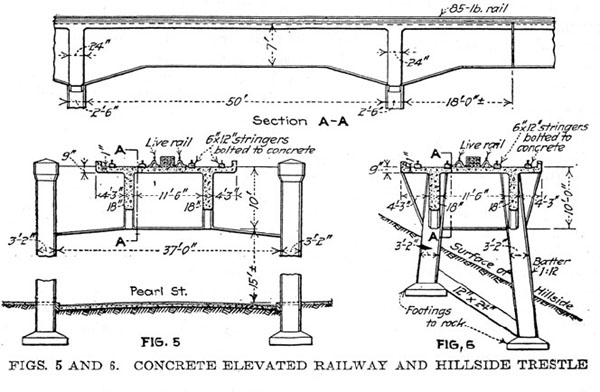

A unique engineering challenge was the section of line built above Columbia Avenue on the unstable hillside between the Eden Park Reservoir and O’Bryonville. Edwards envisioned a 6,100-foot concrete trestle running above Columbia Avenue that would solve the engineering problem and provide a spectacular view of the Ohio River and the Kentucky cities of Dayton and Bellevue.

Edwards described the concrete trestle as follows:

The plan is to construct concrete piers about 30 feet apart with their foundations sunk and keyed into the undisturbed material. These piers are to be connected by reinforced concrete beams on which is laid a reinforced concrete floor and the track will be laid in ballast on this concrete floor. The grade of the track is such that the ground is not disturbed between the piers. The width of the trenches in which the piers are built is about one-tenth of the span between piers. The concrete piers will act as an anchor holding back and tending to prevent a downward movement of the earth.

Unlike the Arnold Report, which considered many different belt line configurations, the Baldwin–Edwards Report assumed a fixed beltway route and concentrated on alternatives for a downtown routing.

Scheme Two imagined a downtown loop that closely mirrored Arnold’s. The loop would have three stations: Plum Street between Seventh and Eighth Streets, one beneath the old Fountain Square esplanade between Vine and Walnut Streets and one in Main Street between Seventh and Eighth Streets.

Scheme Three—“Ninth Street Belt Line”—eliminated any use of the canal between Plum Street and Broadway. It kept the same station locations but reached the Mount Adams Tunnel by a circuitous zigzag through the central business district. The station beneath the Fountain Square Esplanade was to remain the same; the Plum Street station was to become the interurban terminal; and the station beneath Main Street was turned east–west beneath Ninth Street.

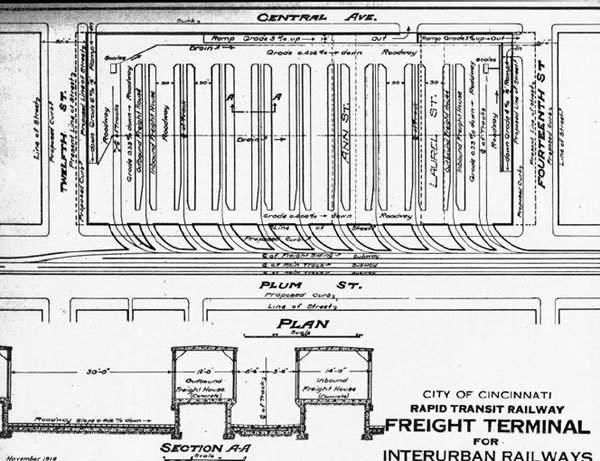

Plan for underground freight terminal to be built on the City Hospital site opposite Music Hall. Courtesy of the Edwards-Baldwin Report.

Scheme Four—”Pearl Street Belt Line”—eliminated the Mount Adams tunnel and reached the eastern half of the loop curving along its base via a steel viaduct above Pearl Street. This scheme greatly reduced the amount of tunnel construction by connecting the canal and the Pearl Street Viaduct beneath Walnut Street.

This 2,700-foot tunnel would include stations between Eighth and Ninth Streets and between Fourth and Fifth Streets. The viaduct would rise immediately from the south end of this station, curve east and have a station above Pearl Street at Butler Street. This land is now occupied by Fort Washington Way and the Third Street Viaduct.

That Scheme Four was recommended by the Rapid Transit Commission is hugely significant, as its Walnut Street portal and Pearl Street viaduct would occupy the area to be claimed by the Union Depot & Terminal Company just a few years earlier. This choice indicates that at this early date the city and business community were in agreement that Cincinnati’s union station should be built in the West End.

Operation of interurban cars on the Rapid Transit Loop would in most or all cases require modification or replacement of equipment, and, in several cases, an adjustment of interurban track gauge. Edwards argued against the installation of a dual-gauge third running rail on the Rapid Transit Loop for use by the broad-gauge interurban railroads, even if they paid for it, because “it is expensive to construct, expensive to maintain and will add to the danger of the derailment of cars with the attendant possibility of accidents to passengers.” Further, his calculations determined that the cost of them changing their own gauges was $38,000 less than the cost for the city to install dual-gauge trackage throughout the loop.

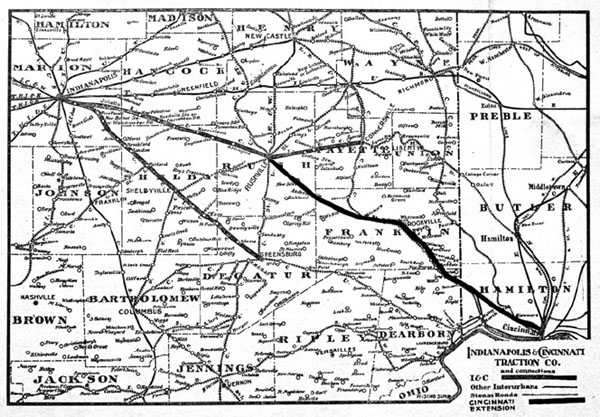

More complicated was the matter of how the interurban cars, which drew their power from overhead trolley wires, could operate in traffic mixed with the electrified third rail of the rapid transit trains. Edwards made no mention of the problem, but preliminary cross-section drawings from 1915 to 1917 show trolley poles and an electric third rail for shared operation. The third rail itself presented a problem for the Indianapolis & Cincinnati Traction Company, as its signaling system was tripped by arms that would conflict with it. Compatibility issues, along with construction of connections and junctions with the loop, were to be the financial responsibility of the interurban railroads.

The Indianapolis & Cincinnati, an interurban built only as far as Rushville, planned to use the Cincinnati & Westwood tracks to enter Cincinnati and join the Rapid Transit Loop near Brighton. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

The second half of the Edwards–Baldwin Report concerns electrical specifications and estimates of cost and was written entirely by Ward Baldwin based on the schemes devised by Edwards. Since production and distribution of electricity had not yet matured, some railroads at that time built and operated their own power plants. Baldwin called for a coal power plant to be constructed, at an estimated cost of $912,000, adjacent to the Cincinnati Waterworks on Eastern Avenue (now Riverside Drive). The riverfront location allowed delivery of coal by barge or railroad and was just two thousand feet from the Rapid Transit Loop’s hillside routing above Torrence Avenue.

The size of this power plant allowed for the simultaneous operation of 36 trains on the Rapid Transit Loop. This rush-hour scenario assumed two-car trains, “on both tracks with a headway of two and one-sixth minutes, at a schedule speed of twenty-four miles per hour, and with one-third minute stops at stations.” Five electrical substations, at a total cost of $225,000, would be spaced evenly throughout the loop. According to Baldwin’s rush hour scenario, on average 4.5 trains would be in operation between substations.

A traffic survey conducted by the city engineer in 1916 generated detailed ridership projections. Overall average daily ridership was estimated to be sixty-eight thousand, with a slight majority of riders originating on the eastern half of the loop. Fountain Square was expected by a wide margin to be the busiest station, with between twenty-five thousand and thirty thousand passengers daily.

Interurban passengers were expected to constitute 18 percent of the loop’s total ridership. As the interurbans ceased operations in the1920s, their bankruptcies were used as an argument against activating the loop. However, the CL&E interurban survived until the late 1930s, and the Cincinnati Street Railway purchased several defunct interurbans and maintained operations as late as 1942. The real danger to the Rapid Transit Loop’s operational finances was not the loss of interurban traffic, but rather a general decline in public transportation ridership.