After the electorate’s approval of Ordinance 96-1917, the Rapid Transit Commission was, per the conditions of the Bauer Act, legally permitted to issue bonds and commence construction of the Rapid Transit Loop. The canal could have been drained and work begun by late 1917, but the United States entered World War I two weeks before the lease ordinance was approved, and soon after the federal government prohibited the sale of municipal bonds.

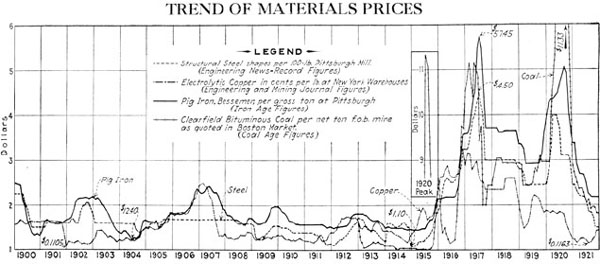

Significant preliminary engineering was nevertheless undertaken in1917 with funds allocated prior to the onset of war, including preparatory work for the Walnut Street subway. But the war did much more than cause a two-year delay—the large-scale sale of gold by warring nations caused a devaluation of those currencies that were backed by it, including the U.S. dollar. As a result, material costs doubled nationwide, and it became clear in 1918, as action in Europe drew to a close, that Cincinnati would be forced to drastically scale back its rapid transit plans.

But the financial situation grew even darker due to ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment on January 16, 1919, just as planning resumed for the Rapid Transit Loop. Prohibition would take effect exactly one year later, closing Cincinnati’s many breweries and taverns, putting thousands out of work and throwing municipal finances into chaos. Diminished tax revenues would inhibit the city’s ability to borrow money, and although legally permitted and in fact petitioned to do so, the Rapid Transit Commission did not seek an additional bond issue for the Rapid Transit Loop before construction commenced. With their obligation to build Central Parkway, the commissioners believed it prudent to begin construction of the parkway soon after completion of the canal subway and then return to the Rapid Transit Loop project. The commission also did not attempt to renegotiate lease terms with the Cincinnati Street Railway until it had a clear idea of how much of the railroad could be built for $6 million.

The economic disruption created by World War I, illustrated dramatically in this graphic, scuttled subway plans in several American cities. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

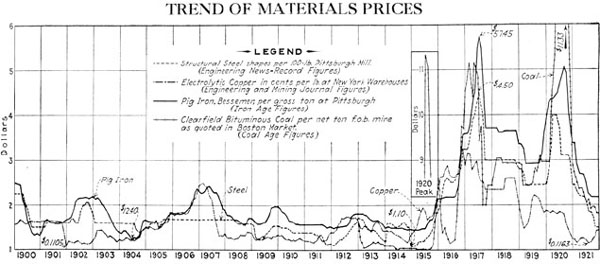

Preliminary design work was performed on the Walnut Street Subway in 1916 and 1917, but no final drawings were made. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

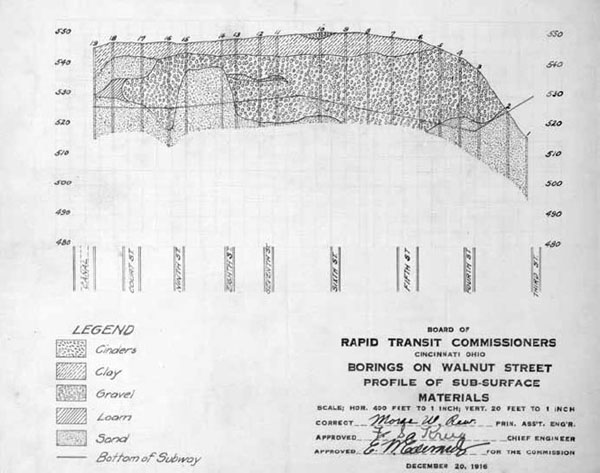

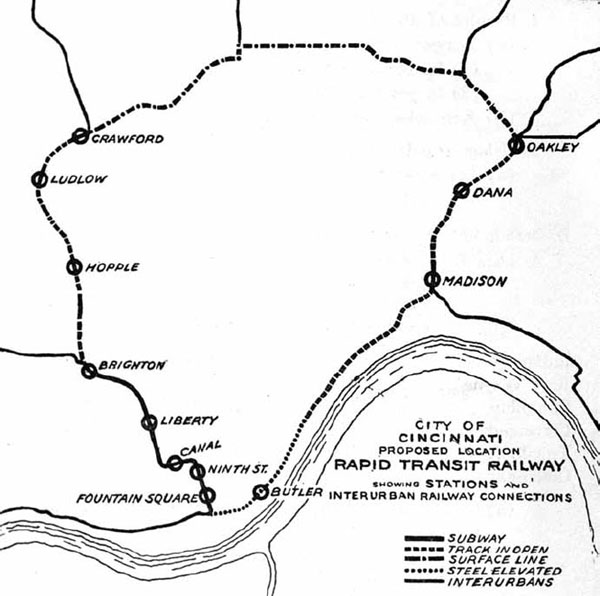

The public was aware as they went to the polls in 1916 that $6 million was insufficient to build the full sixteen-mile Rapid Transit Loop and that it would be built initially as a two-branch system, its temporary terminal stations connected by a new cross-town streetcar line through Norwood and Bond Hill. But due to the factors mentioned above, it was now impossible to build the compromise known as Modification H. In mid-1919, the Rapid Transit Commission dismissed Modification H, made no plans to build the loop’s eastern branch, and resolved to build only the western half of Scheme Four from the Edwards–Baldwin Report.

The new plan that was approved restored the concept of a fully grade-separated rapid transit routing through St. Bernard, Bond Hill and Norwood in place of the Ross Avenue crosstown streetcar of Modification H. It also extended the rapid transit route outside any originally conceived beltway alignment to a terminal station at Madison Road near Cincinnati Milling Machine (later and better known as Cincinnati Milacron), a decision undoubtedly influenced by the appointment of the company’s president to the Rapid Transit Commission. This extension east from Norwood would be built on Enyart Avenue, a platted but unimproved street parallel to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad already owned by the City of Cincinnati.

In its most dramatic cost-cutting move, the Rapid Transit Commission decided not to construct the Walnut Street Tunnel and Fountain Square station. The reason for this decision appears to have been that construction of this section might, in a worst-case scenario, have proven so costly and consumed so much of the $6 million bond issue that the canal subway might not have been finished. With an incomplete canal subway, Central Parkway could not have been built, and the Rapid Transit Commissioners would have failed to complete one of their core tasks.

In a final effort to cut costs, in January 1919, the commission adopted a resolution to acquire properties along the west side of the canal from a point just north of Liberty Street (where the Samuel Adams Brewery is located today) to Mohawk (Linn Street intersection) with the intent to construct this half mile in an open cut adjacent to the future parkway. In order to comply with conditions of the Bauer Act, this construction was required to be entirely outside the bounds of the canal property leased from the state. The matter was studied but abandoned just a month later after it was found that the high cost of property acquisition offered no cost advantage.

The Modification H plan sold to voters in 1916 included rapid-transit lines to the east and west and a streetcar line across Norwood. Courtesy of the Interurban Rapid Transit Bond Issue Campaign Committee.

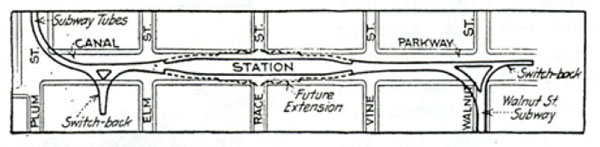

With the decision in February to build the canal subway as originally planned, final drawings were ordered and the two-mile tunnel, divided into four contracts, was put out to bid midsummer, and a dam was built at the Plum Street elbow and another at Ludlow Avenue. The stretch between Plum Street and Sycamore Street was drained in September 1919 and contracts one and two were awarded in November.

Due to World War I inflation, plans were reworked. Only the west side of the loop was to be built initially, but the Norwood streetcar line was replaced by a continuation of the rapid-transit line east to Madison Road in Oakley. The Walnut Street subway and eastern half of the loop pictured in this map could not be built with the $6 million bond issue. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

Section One, site of the Race Street interurban terminal and its associated track work, is the most interesting part of the subway. It was built by D.P. Foley Construction, who earlier built large concrete structures such as the Park Avenue bridge over Kemper Lane and the Mill Creek Interceptor Sewer. Ironically, Foley was contracted in the 1950s to demolish sections of the Rapid Transit Loop including the Ludlow Avenue station as preparatory work for the Millcreek Expressway.

Present-day aerial view of Section One. Courtesy of the author.

Race Street station platforms under construction in 1920. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

The only surviving in-depth discussion of this part of the subway appears in the August 18, 1921 Engineering News Record, a publication not kept at any Cincinnati area library. As a result, for the past ninety years, the station’s design and various dead-end side tunnels have confused its many legal and illegal visitors.

Its central feature, the interurban terminal, was also to temporarily serve the subway’s rapid transit trains. Because the interurban terminal was designed for two-car interurban trains measuring 150 feet in length, rapid-transit trains would also be temporarily limited to a similar length or risk having train doors blocked by the waiting area’s pillars. Four turnout stubs, visible at either end of the interurban platform, were intended to serve future platforms for longer rapid-transit trains after traffic increased. The staircase at the center of the terminal platform was intended to permit transfers to these future platforms, similar to pedestrian underpasses in New York City’s many four-track subway stations.

Provisions for interurban service included wyes at either end of the station. The east wye was to have been completed as part of the Walnut Street Tunnel, and it exists today as a single-track tunnel extending east from the Walnut Street stubs to a point near Main Street. The west wye extends south under private property between Elm Street and Plum Street. It is in pristine condition since the water main that obscures its existence was installed at roughly the same time spray paint was invented.

Diagram illustrating the Race Street Station’s full five-track plan. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

Diagram illustrating the Race Street Station’s full five-track plan. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

Subway Section One. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

Work on Section One was delayed by a litany of material shortages including steel, coal, wood and even lime and burlap, and although work technically began in January 1920, progress was piecemeal until June. The Rapid Transit Commission awarded Foley an extension to its fifty-four-week contract in acknowledgement of these material shortages, and in the interest of progress on the project, City engineer Frank Krug approved the substitution of various materials. For example, Section One was built with a lower-quality steel rebar than originally contracted; Krug allowed its use as long as 20 percent more was used. In 1921, there was a lumber shortage, and the type of wood outlined in the bid books for use as rail stringers was not available.

These change orders gave rise to the rumor that the subway was poorly built. This is obviously not the case, as it has required minimal maintenance in the eighty years since it was built. Tellingly, Section One was not a focus of 2010’s Rapid Transit Tubes Joint Replacement project.

Walnut Street stubs and east wye construction in 1920. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

West Wye under construction between Elm Street and Plum Street. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Section One nearing completion in October 1920. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Race Street station cross-section schematics. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Present-day view of the track switching area and water main west of the Race Street station platforms. Courtesy of the author.

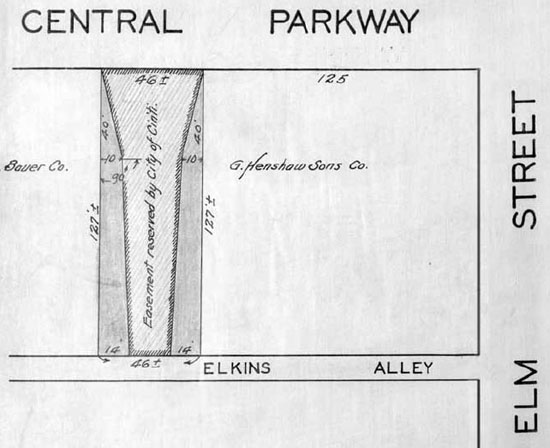

West wye and its easement. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

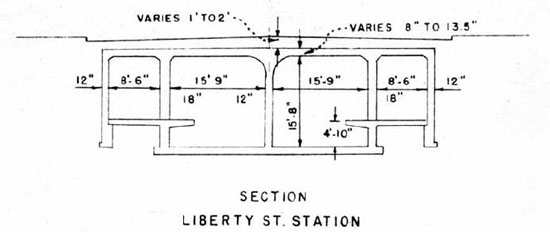

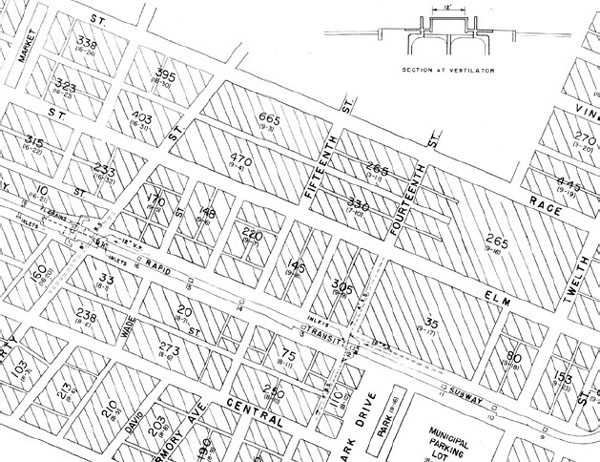

Sections Two and Three were both built by Hickey Brothers of Columbus, Ohio, and compose the simplest and most inexpensively built mile of rapid transit subway in the United States. Combined, these two sections cost $1,050,000 in 1920s dollars, and their construction involved little more challenge than the construction of a similar tunnel beneath a cornfield. Utilities crossed it at just three or four places north of the elbow, but none ran parallel to the canal. Streetcars crossed Sections Two and Three on just two bridges: one at Twelfth Street and another at Liberty Street.

Present-day aerial view of Sections Two and Three. Courtesy of the author.

Liberty Street cross-section. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

The monotony of these two sections is broken only by the Liberty Street Station, provisions for another subway station at Mohawk and turnout stubs for the never-built underground freight depot at the former City Hospital property opposite Music Hall. The Liberty Street Station is situated slightly north of Liberty Street, and entrances were built on the northeast and northwest corners of Central Parkway. Today, only the northeast entrance remains, as the east entrance was probably blocked as part of the Liberty Street widening project.

The station’s east platform was converted into a demonstration nuclear-fallout shelter in the 1960s. The conversion involved minimal structural modifications, limited mostly to installation of permanent lighting and plumbing for toilets and decontamination showers. An alarm system was allegedly installed, but it did not prevent the ransacking of the station by vandals in the 1980s. Since that time, dozens of the bomb shelter’s water canisters have been taken as souvenirs, and few remain.

View of Section Two construction near the freight terminal stubs. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Section Two schematic drawing. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Section Three schematic drawing. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Damaged building near Findlay Street in 1921. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

At Liberty Street, the subway’s ventilation design changed. Sections One and Two were ventilated by regularly spaced box-shaped housings in Central Parkway’s landscaped median. These vents were removed in the 1950s. North of the Liberty Street Station, Section Three’s ventilation was provided by grates on either side of Central Parkway. This design continued north through Section Four.

With work underway on Sections One, Two and Three, the Rapid Transit Commission planned to issue $1,500,000 in bonds in January 1921 in order to fund construction of Sections Four and Five, with each contract amounting to approximately $500,000, and to purchase $500,000 worth of property between Mohawk and Brighton to be used by Central Parkway. This action was delayed by Mayor Galvin, who asked the commission to delay this large bond issue several months in order to protect the city’s bond rating. According to this plan, bonds were sold in July and work commenced immediately thereafter.

In contrast to Sections Two and Three, significant engineering challenges were encountered by F.R. Jones, the contractor hired to build Section Four. Between Mohawk and Brighton, subway excavation corrupted the foundations of several dozen homes. In Brighton, the landmark multistory warehouse now known as the Mockbee Building suffered foundation damage as did the Brighton subway station itself, which was partly rebuilt. Although the event affected fewer than one hundred residents and litigation did not delay construction or, in the end, cost the Rapid Transit Commission a decisive sum, the damage was used to argue against future subway construction.

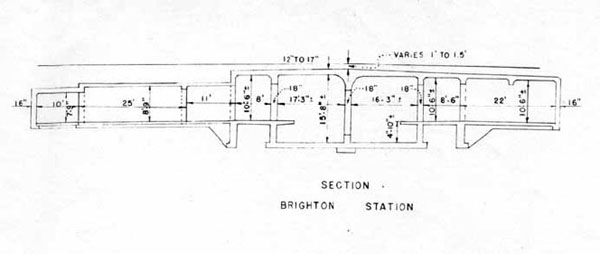

Brighton Station cross-section. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Section Four schematic. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

After the subway was built, an earthen ramp was built to replace the old stone and iron Brighton Bridge. This ramp remained for about five years until it was replaced by a new all-concrete Brighton Bridge, built as part of the Central Parkway Project. This is the only one of four originally planned bridges to have been built over Central Parkway; however, the Dixmyth Avenue Bridge will finally be built as a Martin Luther King Drive–Hopple Street overpass as part of the upcoming I-75 reconstruction.

Section Four ended about one hundred feet north of the Brighton subway station and temporary ramp and only a few photographs taken during initial construction of Central Parkway show these temporary subway portals. These photographs give no indication as to what type of door or other covering was used to block access to the subway during this time period. In 1926, the subway was extended north from this point, but no excavation was necessary as Central Parkway was built as a bridge structure over Section Five north to Draper Street.

Present-day view of Brighton, looking south. Courtesy of the author.

Landslide damage to the Bright Station in November 1922. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Excluded for topographical reasons from the Rapid Transit Loop plan was the Cincinnati, Lawrenceburg & Aurora, an electric interurban railroad that terminated at Anderson Ferry. Passengers were forced to transfer near the ferry slip to the broad streetcars of the Cincinnati Street Railway, which made slow progress from that point into the city. In 1915, the City of Cincinnati granted a franchise to the West End Rapid Transit Company, which planned to build a mile-long viaduct over the Mill Creek and nearby railroad tracks and deliver the CL&A’s interurban cars to a terminal facility on Third Street.

Private financing for this project collapsed during World War I, but the concept was revived in 1919, with hopes that it might be publicly funded. In 1920 the Rapid Transit Commission denied the request of a petition signed by hundreds of Saylor Park residents to place a $1 million bond issue on the ballot, and no improvements were made. The awkward Anderson Ferry transfer continued until 1930, when the defunct CL&A’s track was purchased by the Cincinnati Street Railway, converted to broad gauge, and carried streetcars into former interurban territory until 1940.

Freight was a significant part of the CL&A’s business, and failure of the viaduct project motivated the tiny railroad, like the other interurbans, to truck its freight between Cincinnati and its terminus. But in an innovation with global implications, it created its own purpose-built steel shipping containers that were quickly transferred between its trucks and rail cars by an overhead gantry. This operation only survived for about five years, but word of its effectiveness spread quickly through numerous articles in engineering journals. Although someone somewhere would have eventually invented multimodal container shipping, like so many interesting footnotes in Cincinnati’s history, it has been forgotten.

The CL&A invented multimodal container shipping in the early 1920s. Courtesy of the Engineering News-Record.

The West End Rapid Transit line would not have been a fully grade separated railroad similar to the Rapid Transit Loop as the interurban cars of the CL&A were planned to travel in Third Street for at least a mile in their approach to Dixie Terminal. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.