Unlike Rapid Transit Loop contracts one through four, which survive in the form of the Central Parkway subway tunnel, little remains of contracts five through nine. North of the subway’s Draper Street portals, eight of nine planned miles were built northeast to Oakley, including three surface stations, seven overpasses, four underpasses and three short tunnels. Like the Central Parkway subway, no track or electrical equipment was installed. Exclusive of real estate and engineering costs, a total of $2,050,000 was spent constructing the two-mile subway, but just $1,575,000 on the eight-mile combined distance of sections five through nine.

Hopple Street is the northernmost point where Central Parkway was planned to be built directly over the Rapid Transit Loop, and this eventuality appears to have influenced the small size of Section Five relative to Section Six. Ludlow Avenue would have divided the two contracts more equally, but as-built, $150,000 Section Five was the Rapid Transit Loop’s smallest contract.

Looking ahead to Section Six and beyond, in 1922, the Rapid Transit Commission investigated use of land parallel to the B&O Railroad by the Rapid Transit Loop as an alternate to the canal. On September 8, members of the commission rode a chartered train to Norwood and back, noting the space adequate for two additional tracks. No freight spurs or passing sidings existed along the south side of the B&O mainline for three miles, and due to topography, it was unlikely that any would ever be built. Aside from cost savings, such a routing would free this section of the line from the constraints of the Bauer Act and ease the eventual construction of Central Parkway between Ludlow Avenue and Mitchell Avenue. But after further study, the cost savings were shown to be minor, as the section built in place of the canal cost just $325,000 or approximately as much as one block of the unbuilt Walnut Street subway.

Present-day view of the subway’s portals. Courtesy of the author.

Present-day aerial view of Interstate 75 at site of Marshall Avenue station. Courtesy of the author.

Nothing whatsoever remains of contract six between the Ludlow Avenue Viaduct and Mitchell Avenue, which originally included the Ludlow Avenue station, an overpass and station at Clifton Avenue and another overpass over Mitchell Avenue.

The Hopple Street tunnel was built over previously graded Section Five right of way in 1926–1927. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

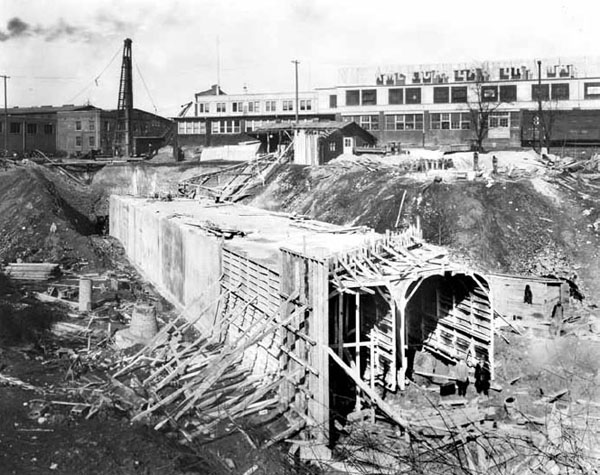

Construction near Bates Avenue in October 1922. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

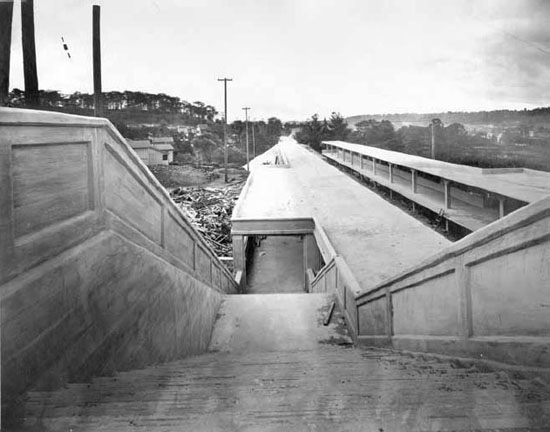

View of the Ludlow Avenue Station from the Ludlow Viaduct. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Earthwork near canal, somewhere on Section Six. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

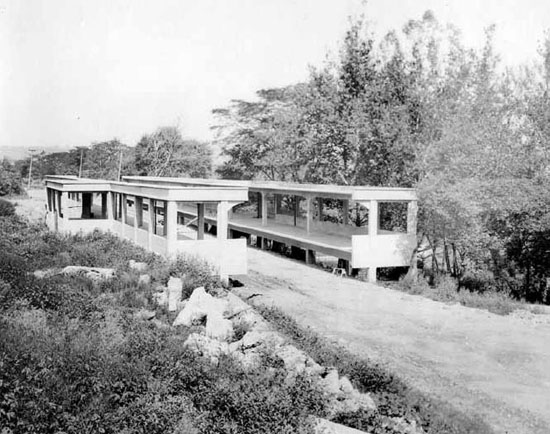

Clifton Avenue Station. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati. St. Bernard Ordinance. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

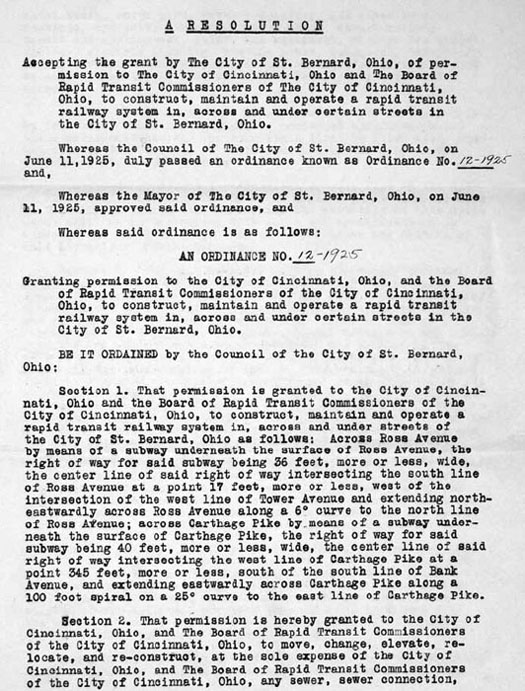

St. Bernard Ordinance. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

Present-day view of Rapid Transit Loop Section Seven right of way in St. Bernard. Courtesy of the author.

Uncertain in 1920 as to how much the $6 million bond issue could build, the Rapid Transit Commission waited to begin right of way acquisition and design work for the route through St. Bernard, Bond Hill and Norwood until the canal subway was complete. Whereas only minor pieces of bordering property were necessary to build along the canal, beginning in 1924, the commission acquired easement or title to approximately one hundred pieces of property of all shapes and sizes between the canal and the line’s terminus at Madison Road in Oakley.

Between Bond Hill and Oakley, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was built in the 1850s on a perfectly straight alignment for a distance of over three miles. As predicted in Arnold’s 1912 report, the area was developing quickly in the mid-1920s, and due to new industries built along Ross Avenue, the Rapid Transit Loop’s alignment was shifted two thousand feet north to open land north of the B&O mainline.

The Rapid Transit Commission was able to cheaply secure right of way through open lands between the canal and Section Avenue. This included a route across the seventy-acre farmlands of the St. Aloysius Orphanage, purchased for $20,700, and a total of $28,296 worth of property purchased from the City of Norwood, with the bulk of it in Waterworks Park. A 248-square-foot parcel near the Norwood Incinerator, probably the smallest piece of property involved in the entire project, was purchased for $62.

The Rapid Transit Loop reused the B&O’s bridge over the canal north of St. Bernard. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Grading near the St. Aloysius Orphanage in August 1924. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Section Avenue Tunnel preliminary work. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

In 1924, the property on both sides of Harris Avenue east of Montgomery Road was owned by the Boss Washing Machine Company, which, as luck would have it, did not completely fill the odd-shaped piece of land between Harris and the B&O. Easement was granted for $4,529, and in 1926, the Rapid Transit Commission was able to build a tunnel beneath Harris Avenue of just nine hundred feet in length, a significant savings over the 1914 plan, which planned a tunnel in excess of two thousand feet. The Boss Washing Machine property was later overtaken by Zumbiel Packaging, a building that was eventually expanded to incorporate the tunnel’s portals into its basement. This tunnel was filled in 2004.

Present-day view of the Harris Avenue Tunnel. This tunnel was filled in 2004. Courtesy of the author.

The Rapid Transit Commission was less fortunate a half mile west, where by odd coincidence another washing machine company, the American Laundry Machinery Company, drew up plans in 1924 for a four-story factory and did not grant easement across its property. The line was originally to have crossed diagonally beneath the intersection of Ross and Section Avenues and continued a diagonal path across open land to an underpass beneath Montgomery Road, immediately north of the B&O underpass; instead, the Rapid Transit Commission was forced to build a tunnel of about seven hundred feet in length beneath Section Avenue, a street that did not physically exist ten years earlier.

East of Forest Avenue, a contiguous right of way to Madison Road in Oakley was acquired, but no construction work was performed east of Norwood Waterworks Park. As part of the Edwards–Baldwin plan, the Rapid Transit Loop was to have traveled through the park to the present location of the park’s tennis courts and then passed beneath the B&O mainline on an alignment just west of Beech Street. The loop would have traveled due south in an open cut parallel to Beech Street, opposite U.S. Playing Card, to a station between Smith Road and Edmonson Road.

Instead, in order to reach the newly conceived terminus at Madison Road, the Rapid Transit Loop was redirected to parallel the B&O mainline and pass beneath it just west of the stone arch Duck Creek Road underpass, which dates from the B&O’s original construction in 1855. A small piece of property was acquired from U.S. Playing Card south of the B&O and west of Duck Creek Road; from that point, the Rapid Transit Loop was to pass over Duck Creek Road and then travel east across undeveloped property that is now Interstate 71.

View of construction in Norwood Waterworks Park. This marked the easternmost extent of construction. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Present-day view of Norwood Waterworks Park. The Harris Avenue tunnel is at bottom right. Courtesy of the author.

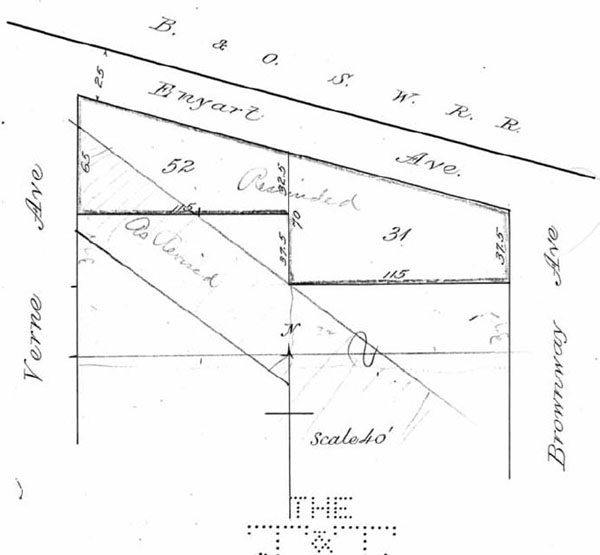

East of today’s I-71, the Rapid Transit Loop reentered Cincinnati and was planned to be built on a three-thousand-foot strip of city-owned property east to Madison Road. Enyart Avenue, which existed only on paper, paralleled the B&O mainline and in concept offered a perfect right of way. Unfortunately, the situation was complicated by a freight siding along the B&O’s south track that was used by one or more of the small companies located south of Enyart Avenue. The Rapid Transit Commission was unable or more likely unwilling to secure a straight right of way by power of eminent domain and was forced to make an odd deviation from Enyart Avenue between Verne Avenue and Appleton Avenue to accommodate the tiny Fitch Dustdown Company.

The right of way acquired near Enyart Avenue in Oakley followed a circuitous route through the neighborhood. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

Present-day view of Madison Road near the abandoned Cincinnati Milacron complex. The Rapid Transit Loop’s Section Nine was planned to terminate at this point, but no work was undertaken on this section. Courtesy of the author.

The Fitch Dustdown Company, manufacturers of “‘Dustdown’: a powder for dustless sweeping and non-trackable floor brushes,” refused to sell the part of its property immediately south of Enyart Avenue, where it accessed the B&O’s freight siding. It demanded damages of $21,000 in granting easement to the Rapid Transit Commission through the center of its property; therefore, the entire alignment east of that point had to be moved south of Enyart Avenue in order to maintain access to the north parcel.

Through this hassle and expense, the marooning of Fitch Dustdown was avoided, but north of St. Bernard where the Rapid Transit Loop deflected east from the canal, an inaccessible island was formed between it, the B&O mainline and Norfolk & Western yard. The owner of the property, Maurice E. Lyons, demanded that a bridge or underpass be constructed in order to provide access, but it is unclear as to whether either were actually built. Construction of a crossing might have been delayed until tracks were laid since the graded Rapid Transit Loop right of way did not present a barrier to people or tractors. This island, measuring 1,500 by 300 feet, was also a prime location for the line’s storage yard and shop facilities, but acquisition of any lands for that purpose were not pursued as they would be the responsibility of the line’s lessee. When the Millcreek Expressway and Norwood Lateral were constructed in the 1950s over the exact route of the Rapid Transit Loop, no access was provided to this area.

Construction of the Section Avenue tunnel and other modifications to Sections Seven, Eight and Nine meant insufficient funds were available to complete Section Nine east of Norwood Waterworks Park. A contiguous right of way was secured between the park and Madison Road, but the $6 million bond issue, as well as proceeds from the sale of small pieces of surplus property, were exhausted by 1927 and no more work could be undertaken. As priority was made of securing this right of way, no stations were built along this stretch.

In 1926, the Rapid Transit Commission reentered negotiations with the Cincinnati Street Railway. Automobile ownership had doubled since 1920 and streetcar ridership’s upward trend, unbroken for thirty years, began a steady decline. Meanwhile all of the interurbans with the exception of the College Hill line had gone out of business. It was a radically different economic environment than in 1917, when Cincinnati voters approved Ordinance 96-1917, and figures from the 1916 Traffic Report that the ordinance had been based on were no longer of any use. Before negotiations between the City of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Traction could begin, a new traffic study was needed.