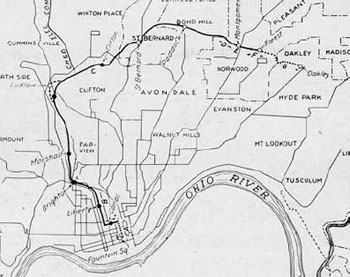

When subway construction began in 1920, it was announced that the Rapid Transit Loop, to whatever extent it could be built with the 1916 $6 million bond issue, would be completed and operational by 1925. But delayed bond issues and technical and legal issues in Brighton and St. Bernard meant that construction of contracts seven, eight and nine did not commence until 1926. Construction of the final section of the loop between St. Bernard and Oakley coincided with the beginning of physical work on Central Parkway. Included as part of the Central Parkway project and built in 1926 and 1927 were the short Hopple Street subway tunnel and an extension of the canal subway north from Brighton, including the portals still visible from I-75.

Amid this variety of road and railway construction, in January 1926, Cincinnati’s municipal government experienced an instantaneous and nearly complete turnover of elected officials and staff. City Hall, county government and some state representatives of southwest Ohio had since the 1880s been controlled by the Republican political machine built and administered by George “Boss” Cox. The machine is believed to have influenced the conditions of the 1911 canal lease and the language of the Bauer Act, and the machine-appointed Rapid Transit Commission made the decision to allow contracts for subway construction after the Ohio Supreme Court tossed out Ordinance 96-1917.

George “Boss” Cox. Courtesy of Bossism in Cincinnati.

Parkview Manor, the mansion built by Boss Cox on Jefferson Avenue in Clifton, served for more than fifty years as a Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity house. In the upcoming decade, it is planned to become the Clifton branch of the Cincinnati-Hamilton County Public Library. Courtesy of the author.

The Cox Machine maintained control by maintaining an avuncular public image. At times, Cincinnati’s thirty-two-member city council was comprised mostly by bartenders, and Cox, himself a former saloonkeeper, famously blocked enforcement of Ohio’s Sunday liquor laws. Top men under Cox were August Hermann, who owned the Cincinnati Reds between1902 and 1927, and Rudolph Hynicka, who was part owner of Coney Island Amusement Park and its horse track.

Rudolph Hynicka. Courtesy of Bossism in Cincinnati.

In the early 1920s, a group of young Republicans, led by local attorney Murray Seasongood, challenged and, after a two-year campaign, drove the Republican Machine out of City Hall. Whereas the machine’s officers and ward captains celebrated their humble origins, freely advertised their lack of formal educations and presented themselves variously as Catholic or Protestant to suit the demographic of each ward, Seasongood was born to a prominent Jewish family, was raised in a mansion on East Eighth Street facing Piatt Park, attended boarding school in England and earned undergraduate and law degrees from Harvard University.

Unlike previous reform attempts, which confronted the machine while it was at full strength, in 1923, the organization was in crisis. After George Cox’s death in 1916, control of the machine shifted to Rudolph Hynicka, who in 1917 moved permanently to New York City where he managed a chain of burlesque theaters. From this outpost, he still controlled Cincinnati government and “The Coney Island of the West” while living a short subway ride from the original Coney Island.

Murray Seasongood. Courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

When Cincinnatians asked why they paid the highest tax rates permissible under Ohio law, and why their city was in more per capita debt than any other city in the United States, the machine pointed to the new Waterworks and General Hospital, its two greatest civic projects until Central Parkway and the Rapid Transit Loop. By the early 1920s, General Hospital alone had come to pinch municipal finances to the tune of $600,000 annually, and interest on Rapid Transit Loop bonds cost the city nearly $1,000 per day.

Meanwhile, city income was inhibited by a variety of unscrupulous activities: property assessments were cooked for party members, and fees and fines of all kinds found their way into the pockets of patrons instead of the city treasury. The situation promised to come to a head in 1925, when a state law permitting Ohio’s cities to levee an additional 2.5 mills above their 10.0-mill maximum property tax was scheduled to expire, reducing Cincinnati and the machine’s annual income by approximately $1,800,000.00.

After 1915, the machine annually filled budget shortfalls with special bond issues, and the November 1923 emergency bond campaign provided an event around which Seasongood’s reform attempt could be rallied. The first move toward that end was made October 9, 1923, when Seasonood’s debut political speech, printed in all three daily papers and dubbed by Seasongood himself “The Shot Heard Round the Wards,” railed against this bond issue. His speech made this mention of the Rapid Transit Loop project: “What is to come of the rapid-transit plan? Ask anyone on the street, and he will shrug his shoulders. Ask the officials of the city. They do not know.”

The November 1923 bond issue, which would not have funded the Rapid Transit Loop, failed along with the second attempted Central Parkway bond issue. The margins of defeat were so great that they would have failed even without Seasongood’s efforts, but he made certain that he was popularly identified with their failure.

Throughout 1924, Seasongood built a case for his reforms, which prescribed institution of a city manager form of government, a weakening of the mayor and reduction of the number of city councilmen from thirty-two to nine. This last feature was important: a nine-member council selected by proportional representation promised to send the machine’s thirty-two ward captains into a fit of infighting. These ward captains were pillars of the community. The best known, Mike Mullen, captain of the Eighth Ward, held an annual picnic at Coney Island that, at its peak of popularity, drew over twenty-five thousand. He, like many others, provided the poor of his ward with coal as winter and the November elections approached and then paid them between ten cents and a dollar as they walked to the polls.

Ward captain Mike Mullen sells Coney Island picnic tickets to neighborhood boys. Courtesy of Bossism in Cincinnati.

The ballots themselves were tipped in favor of the two national parties; bird emblems were printed next to Republican and Democrat candidates for the benefit of the city’s illiterate, but the names of independent candidates or nonpartisan charter amendments were “birdless.” Seasongood drew attention to his nonpartisan ballot issues in 1924 with his “Birdless Ballot League,” an organization that campaigned for his charter reforms throughout the year, including the late summer while he toured Europe for two months. Despite Seasongood’s conspicuous absence and the presence of two decoy charter amendments placed on the ballot by Hynicka, the charter reforms that reshaped municipal government and are still largely in effect today passed by a 2–1 margin.

The new charter did not take effect for a year, and the subsequent orchestration of a Charterite takeover was helped by Central Parkway’s complicated preparatory work. Throughout 1925, a team of surveyors and lawyers were busy defining the parkway’s tax assessment zone for sixteen thousand assessed properties. Seasongood made the poor condition of the city’s streets a major part of his argument against the machine; a completed Central Parkway would have dazzled the public and diffused his argument. The parkway could have been completed by 1925 if the 1921 bond issue had passed, but eighteen months after the electorate finally approved parkway bonds in spring 1924, there was no construction activity.

Little more than two years after his “Shot” speech, in November 1925, Seasongood and five other Charterites were elected to the new nine-member council. In order to secure power and fend off the machine in the long term, they had to make their campaign promises a reality—to the detriment of the Rapid Transit Loop. The new government was able to improve city finances quite easily by simply collecting all property taxes, fees and fines and eliminating patronage staff. They were able to carry out long-delayed projects such as installing new street signs and traffic signals while reducing the city’s debt for the first time since 1915. Additionally, the image of Seasongood and the Charterites was helped immeasurably by projects they had nothing to do with: the new Eight Street Viaduct was built by the state, and work on Central Parkway began just months after they took power. This all-new government had no direct control over the Central Parkway project or the Rapid Transit Loop project since the Rapid Transit commissioners, all machine Republicans, served ten-year terms.

Work continued on the Rapid Transit Loop in Bond Hill and Norwood, but by 1926, it had crossed a financial Rubicon: raising capital to complete the loop was one matter, but the specter of perpetual operational subsidies was another. This situation complicated the task of administrating the project, since the commission was in charge of finishing the Rapid Transit Loop and negotiating its lease, while city council would have to approve an operations budget, an eventuality for which no provision existed in the Bauer Act. This task would therefore require cooperation between the Charterites on council and the elected and appointed Hynicka-controlled members of council and the Rapid Transit Commission. Instead of working to build such coalition, Seasongood picked a headline-grabbing fight that stalled the project for the duration of his four year mayorship.

The charter reforms reduced the power of mayor to that of an ordinary councilman with no veto powers. The mayor was not elected directly and was instead selected behind closed doors by a caucus of his fellow councilmen, a process designed to intrigue the public. Seasongood, despite finishing second in voting, predictably emerged victorious and, upon taking office in January 1926 with the backing of his 6–3 majority Charterite council, immediately set about cleansing City Hall of all old Republican appointees. This was accomplished by eliminating city departments, then ordering the newly instituted city manager to create a replacement department with a new name and new staff.

First to be eliminated was the City Engineering Department, including chief engineer Frank Krug, whose home stood immediately next to the famous Boss Cox mansion on Jefferson Avenue. Krug had been an integral part of both the Rapid Transit Loop project and the planning of Central Parkway but had long been the object of criticism for having drawn a $4,000 salary as a Rapid Transit commissioner in addition to his $6,000 salary as chief engineer.

The only office protected by state law from Seasongood’s purge was that of the City Auditor. Seasongood periodically lobbed mud at auditor Alfred Deckebach but directed most of his energy toward dissolving the Rapid Transit Commission—or rather drawing out its dissolution. Theoretically, the commission could have been dissolved instantly by city ordinance and the administration of the Rapid Transit Loop and Central Parkway projects passed to the Office of the City Manager, but Seasongood drew out the dissolution process for three years in order to build a narrative in the press in which he could repeatedly position himself as a hero of the people.

First, the Harvard Law graduate announced that per the language of the Bauer Act, three of five commissioners had served illegally since the failure of the Central Parkway bond issues. This was followed by an effort to strip the commissioners of their salaries and even order them to pay back what salaries they had drawn since their appointments. Neither action was of much legal merit, but Seasongood won the war by keeping these battles in the news for the duration of his first two-year term. He presented his accusations as having been proven true even after they had been discredited by the courts, steadily turning the public against the rapid transit project and quieting calls for its timely completion.

Mayor Seasongood speaks at Central Parkway dedication ceremonies in 1928. Courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books.

View of Brighton Station and water main, looking north from inbound platform. Courtesy of the author.

View of Brighton Station and water main, looking south. Courtesy of the author.

View of the Walnut Street turnout stubs, center, and the east interurban wye, left. Courtesy of the author.

View of the Hopple Street tunnel’s sealed north portal. Courtesy of the author.

View of the decontamination showers installed in the Liberty Street Station’s outbound platform concourse in the early 1960s. Courtesy of the author.

View of bunks installed in the Liberty Street Station as part of its conversion into a bomb shelter. Courtesy of the author.

View looking south on the Liberty Street station’s outbound platform. Courtesy of the author.

View looking north from the Liberty Street station’s outbound platform. Courtesy of the author.

Looking across the station tracks from Liberty Street’s inbound platform to the bomb shelter built on the station’s outbound platform. Courtesy of the author.

Looking up the Liberty Street Station’s east sidewalk staircase. Courtesy of the author.

Looking west across the Race Street station’s island platform. Courtesy of the author.

View of the Race Street station’s west wye, left, and the subway’s turn at Plum Street. Courtesy of the author.

View of the subway’s outbound tube, looking south just south of the Liberty Street station. Fiber optic cables were installed in 2000. Courtesy of the author.

View of the Race Street station’s center layover track. Courtesy of the author.

View of the Race Street station’s center platform, looking west. Courtesy of the author.

The high pressure water main installed in the subway’s inbound tube in the late 1950s shoots water onto the Liberty Street station platforms. Courtesy of the author.

Below: View looking north from the Race Street Station’s west wye. Elm Street is to the right and the subway’s Plum Street turn is to the left. Courtesy of the author.

Having defeated the Republican machine in part by criticizing the absurdity of Hynicka’s long absences from the city, during his first term Seasongood shamelessly left town to tour cities coast to coast espousing the city manager form of government. These speeches were reported in the papers of tour cities and then wired to Cincinnati papers, where his “good government” shibboleths and predictable railings against the Rapid Transit Commission were repeated yet again to local readers. On May 13, 1927, the Cincinnati Daily Times-Star printed a dispatch from Atlanta, where Seasongood, at a “mass meeting in the City Auditorium,” chronicled the perfidies of the Rapid Transit Commission. The paper printed a verbatim account of this part of the speech, which likely took no more than two minutes to deliver, but nothing from the rest of his appearance.

With work on Rapid Transit Loop contracts seven, eight and nine underway well out of sight of City Hall in Bond Hill and Norwood, in early 1926, council considered the merits of a completely separate streetcar subway project known as the “Broadway Subway,” which would have seen Gilbert Avenue and Reading Road streetcars redirected into a new tunnel beneath Broadway south of Ninth Street. After a station at Seventh Street, the tunnel was to curve under Fifth Street to a terminal station under Government Square. This was planned in conjunction with a widening of Broadway that would have required demolition of all buildings on the east or west side of the existing street.

Theoretically, this terminal station could transfer passengers to the Rapid Transit Loop’s future station beneath Walnut Street, and its phony cheerleaders advertised that fact, but Seasongood had no intention of pursuing construction of either tunnel. Avoiding all risk, he and others sought political shelter by commissioning a new report to recommend what should be done with the incomplete rapid transit line. This study, known as the Beeler Report, was a stall tactic and one devised to weaken the case for the loop.

The Beeler Report ignored any potential expansion of the rapid transit line beyond its original conception, most obvious being a northern branch on the canal, which was now in disuse to Lockland. Instead it prioritized service from the yet-unbuilt stations in Norwood and Oakley over those that had already been built—namely Liberty Street, Marshall Avenue and Clifton Avenue—so that rapid transit trains could beat the travel times of shorter streetcar lines from those distant points. The thought of bulldozing never-used surface stations, as was intended, upset the public, as did not using the Liberty Street Station, which was in the center of the most densely populated neighborhood in the Midwest.

Present-day aerial view of the former Cincinnati, Milford & Blanchester interurban right of way near Merriemont. The bankruptcy of the CM&B and other interurbans was used to argue against completion of the Rapid Transit Loop; however, streetcar transfers were always expected to comprise the majority of the loop’s ridership. The CM&B was purchased by the Cincinnati Street Railroad, and streetcar service to Marriemont continued until 1942. Courtesy of the author.

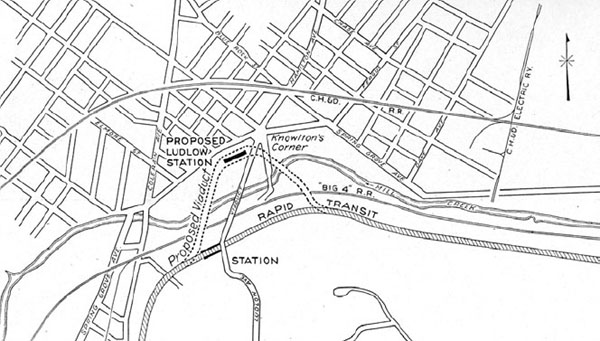

The Beeler Report recommended completion of the line to Fountain Square and Madison Road in Oakley, construction of an elevated Knowlton’s Corner station and abandonment of the Liberty Street, Marshall Avenue and Clifton Avenue stations in order to increase speed. Courtesy of the Beeler Report.

The Beeler Report recommended an elevated station for Knowton’s Corner. Courtesy of the Beeler Report.

Thinly veiled antisubway critiques of the Beeler Report began describing the Rapid Transit Loop as “circuitous,” insinuating that it was planned poorly from the beginning. Other language acted to cast suspicion on the safety of fast operation of the line’s trains and skepticism that the city’s streetcars could operate in the tunnel, when their use was suggested in place of purpose-built rapid transit trains. Seasongood was quoted as saying he was told by those who prepared the report that Cincinnati was “not big enough for a subway,” despite its population having grown 20 percent since the Arnold Report. After the Beeler Report’s completion and presentation, Seasongood complained that since the city manager was not involved in creating the report that yet another study was needed that directly involved his city manager.

Seasongood was reelected for a second two-year term in November 1927. With the Central Parkway project complete and the $6 million Rapid Transit Loop bond issue exhausted before contract nine (the stretch between Norwood and Madison Road in Oakley) could be built, an ordinance was passed by council that called for the Rapid Transit Commission’s dissolution. On January 1, 1929, the commission ceased to exist and all matters relating to the subway and Rapid Transit Loop shifted to the Office of the City Manager.

A second report was completed in 1929 by the Beeler Organization in conjunction with the Cincinnati Street Railway, studying the feasibility of streetcar operation between Ludlow Avenue and downtown on the completed Rapid Transit Loop right of way. This second Beeler Report was relatively simple and took advantage of the line’s strengths, whereas the first Beeler Report, by emphasizing the loop’s weaknesses, intentionally created a proposal with problematic features that could be exploited by Seasongood.

This 1929 streetcar plan came relatively close to fruition. The Cincinnati Street Railway purchased streetcars that could serve the subway’s high platforms, and the Cincinnati & Lake Erie, the only surviving interurban, purchased several interurban cars with a similar feature. Dual-gauge track was installed at the Winton Road streetcar barn, but since the plan was scuttled by the onset of the Great Depression, the broad-gauge axles on these streetcars and interurban cars were never sawed down, and the standard-gauge tracks at the car barn were never used.

Seasongood’s refusal to move forward with the rapid transit project was surely motivated in large part by the unknowns surrounding the Walnut Street Tunnel. Having seen cut-and-cover subway construction first-hand while attending high school in London in the 1890’s, in Boston for seven years at Harvard University, and while working in New York City as a law clerk, Seasongood more so than other Cincinnati politicians knew that the chaos of subway construction was ripe territory for a revival of Hynicka’s machine.

Whereas the subway beneath Central Parkway was the least expensive subway per foot in the country, the Walnut Street Tunnel would be as difficult and expensive as any in New York or Boston. As construction of this short but difficult tunnel would require approximately two years and inevitably overlap an election, the work in Walnut Street would provide a stage for Hynicka to politically sabotage Seasongood and the Charter movement. A month before elections, Hynicka’s goons could have employed any number of tactics to embarrass Seasongood, ranging from staging strikes to causing a building to collapse.

Failure to move forward on the Walnut Street tunnel meant that the existing tunnel, with its terminus a half mile north of the business district, was useless. All subsequent efforts to use the subway have been hampered by its unfortunate terminus on the edge of the central business district.

To borrow a cliché from today, from the perspective of the Republican Machine, the Rapid Transit Loop was too big to fail. The machine built the new Cincinnati Waterworks in 1907 and General Hospital a decade later; Central Parkway would at last realize a dream envisioned for generations and go a long way toward rebuking complaints about the poor condition of the city’s roads. The subway beneath signaled that the machine could execute large, forward-looking and equitable improvements that were the envy of larger cities such as Detroit, Cleveland and St. Louis.

Subsidizing operation of the Rapid Transit Loop would not have presented a moral dilemma for Rudolph Hynicka. It was a concept with which he was intimately familiar since New York City, where he resided, for political reasons held subway fares to a nickel in the 1920s while streetcar fares in Cincinnati and most of the country rose to between seven and ten cents. New York’s artificially low fares caused political turmoil in the rest of America’s cities—populations nearly rioted in protest of streetcar fare increases in their respective cities, but they were equally upset by the prospect of subsidizing the for-profit traction companies.

But if Hynicka had remained in control, completion of the Rapid Transit Loop, or at least operation of part of it, was not an absolute certainty. Cincinnati was already scraping its debt ceiling, and if the struggle to pass bonds for Central Parkway was any indication, a similarly frustrating fight might have been in store for subway bonds. Meanwhile, except in New York City, where subway lines continued to be built to replace unpopular elevated lines, subways generally fell out of favor elsewhere. Cities that had been considering rapid transit subways were spooked by the unprofitable outcomes of the first New York, Boston and Philadelphia lines, and although they were built to reduce population density by opening up new territory, they actually acted to increase it.

The larger issue is that the financial strain placed on the city by completion and operation of the Rapid Transit Loop would pinch the machine’s unofficial patronage budget. The machine began losing its grip in the early 1920s in part due to annual obligations to General Hospital; operation of the loop would aggravate the situation. The Rapid Transit Loop, had it been put into operation, might even have caused the collapse of the machine in the 1930s, as the drop in tax revenue caused by the Great Depression would have dropped potential payouts.

Murray Seasongood, left, and Colonel Sherrill, Cincinnati’s first city manager, are pictured in this mosaic installed in Union Terminal in 1933. Courtesy of the author.

The charter reforms did not single-handedly defeat the machine; Rudloph Hynicka’s health was poor throughout the two-year reform movement, and he died in early 1927, hardly more than a year after Seasongood took over. A parallel effort to reform county government begun in 1926, known as the Citizen Movement, failed to enact a new county charter, but it meant that the vestiges of the machine, accustomed to fighting one uprising at a time, had to simultaneously battle to maintain its control of county government while plotting a City Hall comeback. August Hermann died four years after Hynicka, and with diminished income during the Depression, the lack of tax income available for patronage discouraged a revival of the machine.

While Seasongood was entirely justified in his overall criticisms of the machine, there is no evidence or that a significant sum of money disappeared in the administration of the loop project by the Rapid Transit Commission. Hynicka’s machine was in financial crisis but needed the Rapid Transit Loop to be a success. If money did in fact disappear, the machine shifted other funds into the account in preparation for the Charterite takeover. “The Report of the Rapid Transit Commissioners,” ordered by Seasongood upon taking office, gives a believable account of the management of both the Rapid Transit Loop and Central Parkway projects.

Seasongood’s strategy, clearly intended to stall the subway project, probably did not intend to completely kill it. Piecing together Seasongood’s words and actions, he was setting the stage for the subway project to be “saved” by him, completed on his terms and then become his victory. But because Union Terminal and the Carew Tower broke ground during his tenure, he didn’t need the subway as a short-term political win. He could not have predicted that automobile use would continue to rise at an exponential rate or that the country would sink into its worst financial period just as he was leaving office. He could not have predicted that, aside from Chicago’s State Street and Dearborn subways, which merely supplemented that city’s famous elevated loop, a new rapid transit subway system would not be built anywhere in the United States until San Francisco’s BART broke ground in the mid-1960s.

Seasongood and the Charter Movement do deserve credit for turning around the city’s finances in short order. Between 1926 and 1940, Cincinnati shifted from being the country’s most indebted to its least indebted city. Revenues were enhanced a favorable renegotiation of the Cincinnati Southern Railroad lease in 1928 and expenditures were slashed by eliminating dozens, if not hundreds, of redundant patronage jobs and ending the practice of securing patronage by paying contractors for work never performed. These increases in revenue and savings were so dramatic that the City of Cincinnati could have easily afforded the construction of the entire sixteen-mile Rapid Transit Loop and operated it at an annual loss of $1 million or more.

But by the late 1930s, when these savings were realized, the subway faced new challenges. Plans advanced for a cross-state turnpike on the canal right of way, placing the state’s bulldozers on a collision course with the city’s Rapid Transit Loop. Meanwhile a change in state law required 65 percent supermajorities for local bond issues, taking the wind out of a subway revival effort. With no local funding to complete the loop, Cincinnati was nearly helpless to stop its destruction.