In July 1929, the Beeler Organization completed a second report titled “A Report to the Cincinnati Street Railway Company on a Rapid Transit Line Between Central Parkway and Race Street and Ludlow Station, Cincinnati, Ohio”, which discussed the feasibility and finances of what amounted to a rapid transit shuttle between Downtown and Knowlton’s Corner. Four-minute headways throughout the day promised to replace a twenty-five-minute streetcar ride with a nine-minute subway ride and attract 37,000 daily riders.

The report discussed no major modifications to the line such as a Walnut Street tunnel or elevated station in Northside, but did recommend the abandonment of the Marshall Avenue station and construction of a two-mile nonrevenue track on the Rapid Transit Loop northeast from Ludlow Avenue to reach the Winton Road streetcar car barn. This service track could of course have been utilized if service was extended to St. Bernard. Part of it would be used immediately by the CL&E, which survived the interurban meltdown and in the late 1920s purchased new “Red Devil” cars designed for use in the subway.

The report did not discuss how many rapid transit cars would be purchased, but since two trains were to operate in each direction at all times at a maximum length of three cars, no more than fifteen cars were necessary to begin service. According to several accounts, this plan was very close to fruition, and duel-gauge tracks were even installed at the Winton Road car barn. The report was released just three months before the October stock market crash, after which time capital was unavailable for this relatively small project and use of rapid transit trains was never again proposed for the Rapid Transit Loop.

Revival of subway proposals in Cincinnati appears to have been spurred by the 1935 opening of Newark, New Jersey’s “City Subway”, which was also built in place of a canal but used unmodified streetcars instead of rapid transit trains. A special section in The Cincinnati Enquirer printed photos of similar views of each city’s transit lines side-by-side, some of which bore an uncanny resemblance.

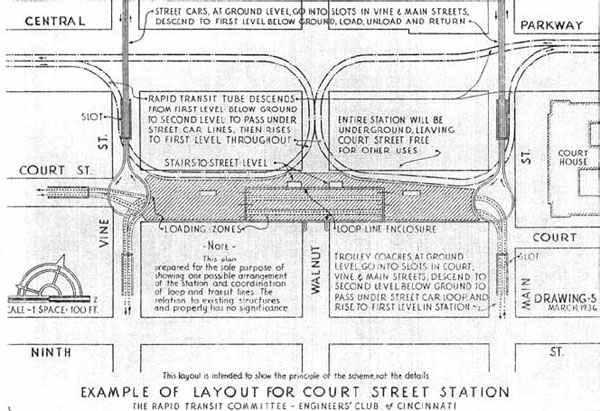

By coincidence, two subway studies were completed in 1936. The first, by the City Engineer’s Club, was not an official study. It suggested use of the Rapid Transit Loop right of way and the two-mile subway tunnel beneath Central Parkway by streetcars, and a downtown streetcar terminal beneath the Court Street Market, where passengers could transfer to electric trolleybuses that would circle downtown streets in perpetuity. According to critics, the inconvenience associated with the modal transfer and the slow movement of the trolleybuses threatened to destabilize downtown property values in favor of the Court Street terminal.

Underground trolleybus transfer terminal as envisioned by the City Engineer’s Club in 1936. Courtesy of the Enginneer’s Club.

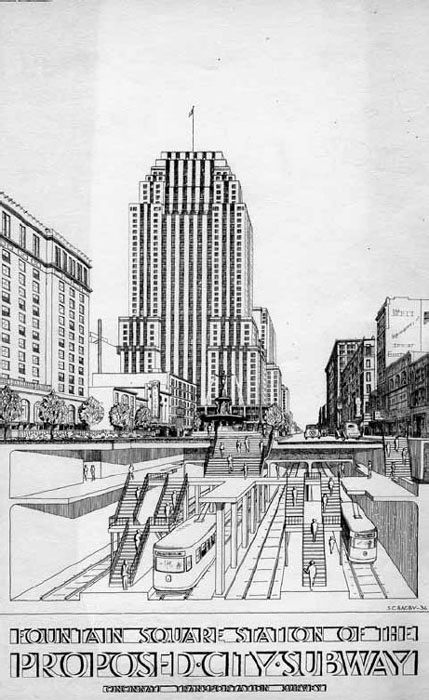

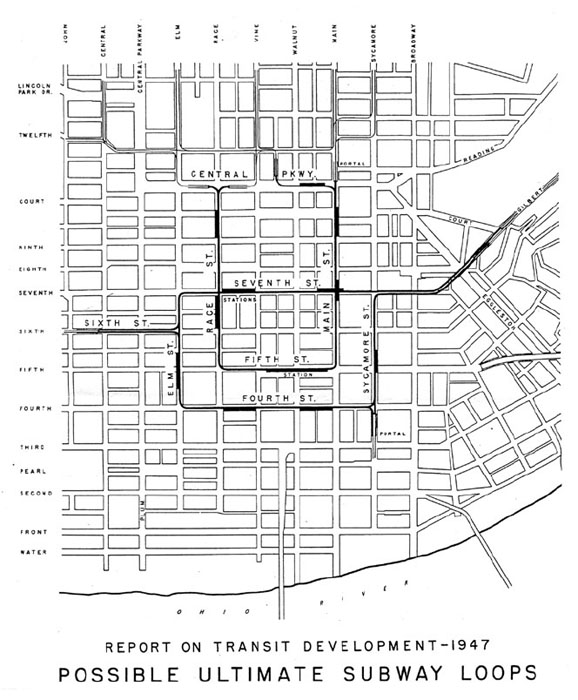

The 1936 “Cincinnati Transportation Survey,” funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), is the more interesting of the year’s two reports. Its survey of streetcar ridership patterns, collected by a crew of seventy men who rode the city’s streetcars every weekday for three months, provided hard data for an application for New Deal capital funds. The report recommended use of the Rapid Transit Loop by streetcars, including the Central Parkway Subway, as far north as St. Bernard, and construction of a streetcar subway loop in the downtown area similar in concept to the downtown loop proposed by Bion Arnold in 1912.

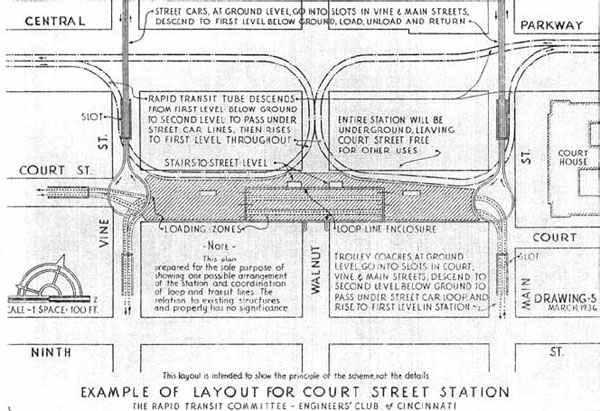

The “City Subway” Fountain Square station. Courtesy of the 1936 Cincinnati Transportation Survey.

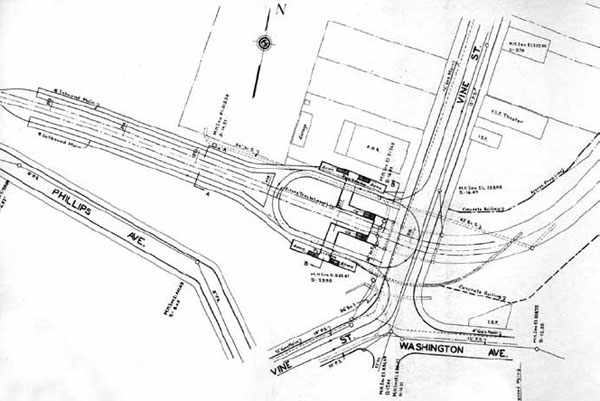

City subway map. Courtesy of the 1936 Cincinnati Transportation Survey.

The so-called “City Subway” was to consist of a double-track loop built under Race Street, Main Street and Fifth Street. Streetcars would enter the loop through the existing Central Parkway subway and several other entry points and circle either the inside or outside track. Stations would be built with center island platforms in order to allow cross-platform transfers, but because all of the Cincinnati Street Railway’s streetcars had doors only on the right side, flying crossovers were planned inside each portal to direct streetcars to the left-side loop track.

Elevated turnaround in St. Bernard. Courtesy of the 1936 Cincinnati Transportation Survey.

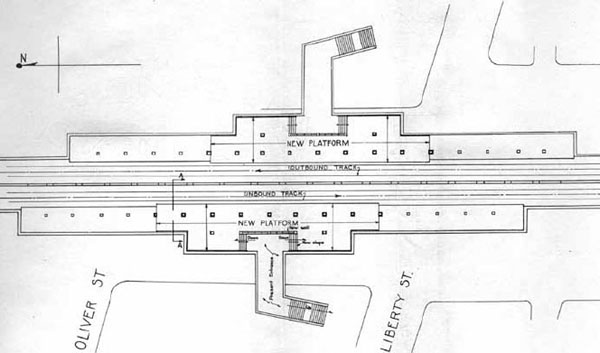

Liberty Street platform modifications, Liberty Street station. Courtesy of the 1936 Cincinnati Transportation Survey.

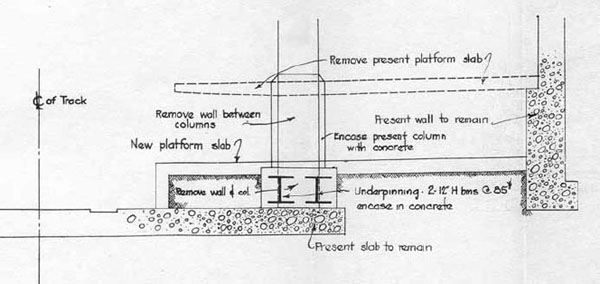

Platform modifications in Liberty Street station. Courtesy of the 1936 Cincinnati Transportation Survey.

The study divided discussion of the City Subway and “Use of Rapid Transit Facilities” into different sections and recommended the funneling of various streetcar lines onto the Rapid Transit Loop route. College Hill and Northside streetcars would join the Rapid Transit Loop at a point just south of Ludlow Avenue, and Western Hills Viaduct streetcars would join the existing subway just north of Brighton. The Liberty Street and Brighton Stations would have their platforms lowered for use by streetcars, as would the Marshall Avenue, Ludlow Avenue and Clifton Avenue surface stations.

The 1936 Cincinnati Traffic Survey estimated the cost of the City Subway to be $4,457,035 and conversion and completion of the Rapid Transit Loop for streetcar service north to St. Bernard to be $1,563,420. Federal funding of 45 percent was possible, which meant a bond issue of at least $3,000,000 was required. It does not appear that the City Subway was part of Cincinnati’s application to the WPA, and instead funding was sought and awarded for construction of Columbia Parkway and its Fifth Street Viaduct, which commenced construction in 1937. The time advantage promised by the Rapid Transit Loop’s unbuilt eastern half was claimed instead by the new parkway and its high viaduct over Eggleston Avenue.

New Deal funds were also awarded to build the basin’s first public housing blocks. About $7 million—more than the subway proposal—was awarded to demolish several densely built blocks of nineteenth-century row houses and replace them with four-floor housing blocks. The entire West End south of Liberty Street and west of John Street, home to more than fifty thousand people, was demolished piece by piece over the next twenty-five years. The original Laurel Homes buildings were demolished in the early 2000s and replaced by City West, a mixed-income development that loosely mimics the area’s original brick row houses.

In 1939, just as political support for a downtown streetcar subway experienced a surge of support, Ohio drastically altered its election laws. In an abrupt departure from simple majorities, beginning in 1939 and until 1949, a 65 percent supermajority was required for major municipal bond issues, making construction of subways, expressways and airports nearly impossible anywhere in the state.

This change did not ice discussion of subway construction, perhaps because it was believed that the situation was temporary. In 1939, a new study advised a plan nearly identical to that described in the 1936 Cincinnati Traffic Survey but avoided its unusual left-track plan by substituting side-platform stations. Streetcars were still favored over diesel buses due to their ability to operate in tunnels without automated ventilation, which was estimated to increase construction costs by $2 million, or approximately 20 percent. Planners also favored PCC streetcars due to their higher passenger capacity, fearing that operation of an all-bus subway might cause traffic jams inside the subway and on the surface near its portal entrances.

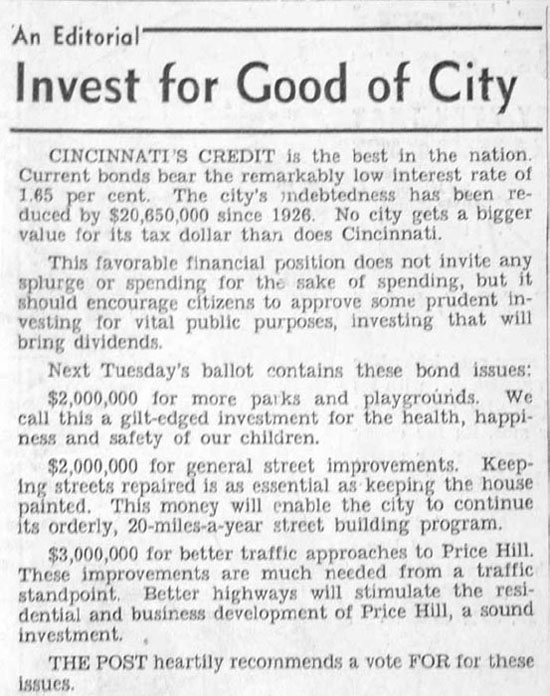

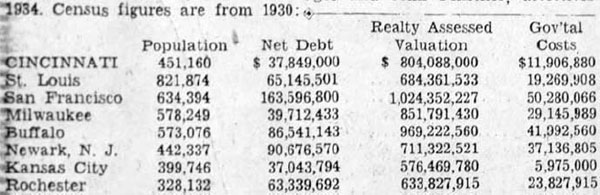

It was announced in August 1940 that this downtown subway plan, which would have cost between $10 million and $13 million, would be submitted to the electorate in 1941. Some expected that a variety of road projects would be bundled with the subway as part of a bond issue totaling approximately $15 million. Cincinnati could easily afford this debt, as its total bonded indebtedness, was reduced by $20 million after the Republican Machine’s 1926 ouster. But as world affairs deteriorated in 1941, the vote was postponed and then set aside as a “postwar project.”

Debt editorial from the November 2, 1939 Cincinnati Post. Courtesy of the E.W. Scripps Company.

In 1949, the state-mandated supermajority was lowered to 55 percent, likely motivated by dozens of failed postwar expressway bond issues. In Cincinnati, failed expressway bond campaigns meant the 65 percent supermajority requirement gave the Rapid Transit Loop a few more years to sit unused. Meanwhile, the law directly affected the placement of the region’s airport in Boone County. Numerous late 1940s airport bond issues won more than 50 percent of the vote but not the required supermajority, and as a result, property acquisition for a major airport in Hamilton County was never sufficiently funded and the region’s airport lost to Kentucky. State law did not return to a simple majority until 1969.

1939 debt comparison graphic. Courtesy of the E.W. Scripps Company.

The various bond issues totaling $6 million sold between 1919 and 1925 were sold according to a fifty-year term dating from 1917 but were redeemable in its twenty-fifth year. In 1940, when the Cincinnati Metropolitan Transportation and Subway Committee advocated a large bond issue for construction of a downtown streetcar subway, it was expected that in 1942, the interest rate of Rapid Transit Loop bonds would be reduced from 5.00 and 5.75 percent to 2.50 percent.

Instead, the economic chaos created by the Second World War permitted the Rapid Transit Loop bonds to be refinanced at an exceptionally low interest rate of 1.25 percent. That year, refunding bonds scheduled to mature in 1966 replaced $4,440,000 of the Rapid Transit Loop’s original bonds. A portion of the original subway bonds held by the Jacob Schmidlapp Trust were refinanced at 4.50 percent, which in a twist came to fund free summer concerts at the Murray Seasongood Pavilion in Eden Park. The inconsistent refinancing of the Rapid Transit Loop’s bonds sparked rumors that the trustees of the Cincinnati Sinking Fund and Schmidlapp Trust conspired to keep the subway from being activated. On May 28, 1965, a letter to the Cincinnati Post asked:

It is our understanding that one of the largest brokerage concerns collects $350,000 a year from the city to pay dividends on outstanding stock issued when the project started. It is also said that as long as this subway lays idle, these dividends will continue, but if this project is ever used commercially, these dividends will stop. That seems to be the reason that anything is brought up to use this facility is discarded or voted down.

With a downtown streetcar subway delayed indefinitely by the war, in 1942, a proposal appeared for the lease of the Rapid Transit Loop south of Ludlow Avenue for freight purposes. In 1943, a city ordinance was passed that described tentative terms for a lease of the subway, and the next year, twenty-six companies near the subway announced an interest in rail service. A group of area businessmen formed the Parkway Industrial Railroad Company, hired their own engineering firm to prepare preliminary drawings, and as a publicity stunt purchased a gasoline-powered locomotive that they claimed would be used in the subway.

Rails were to be laid five miles south from the B&O mainline tracks near the Ludlow Viaduct to the subway’s Plum Street turn. Industries adjacent or near the subway would be served by various new spur tunnels built at its own expense. A single gasoline locomotive, purchased at auction in 1944, was believed to be sufficient to handle all of the freight subway’s traffic.

The proposal was attacked on several fronts. The Cincinnati Metropolitan Transportation and Subway Committee argued that use of the subway by freight trains would complicate or possibly preclude its use by streetcars. Here the track-gauge gremlin appeared once more: the combined use of the tunnel by standard gauge freight cars and Cincinnati’s broad gauge streetcars would require an additional pair of tracks to be laid outside each freight track. Speed of the streetcars would be limited by the many crossings of broad-gauge tracks across standard-gauge turnouts leading to new spur tunnels.

The freight proposal was next attacked on the grounds that, per the conditions of the Bauer Act from 1915, the City of Cincinnati could not lease the subway without its approval by the electorate. Therefore, for the first time in twenty-nine years, a subway matter was placed on the ballot, and in November 1946, Cincinnatians by a 2–1 margin approved a five year lease of the subway to the Parkway Industrial Railroad Company for $32,000 annually.

In the late 1940s, subway proposals shifted to use by electric trolleybuses. Courtesy of Public Transit.

But a lease was not signed and no tracks were laid. Clearly, the junction of the subway railroad and the B&O mainline was in conflict with plans for the Milllcreek Expressway. The unusual geometry of the area created a situation that would have required a multimillion redesign of the Ludlow Viaduct in addition to an elevated expressway. Moreover, since the Millcreek Expressway was being built to improve truck access to Cincinnati’s basin industries, the freight subway would have lost most of its business shortly after its construction.