F. Tannenbaum, ‘Life in Concentration Camp’ series, Belsen, 1945

10th October 1945

This is to give you a description of the day I spent in Luneberg, at the trial of the War Criminals associated with Belsen and Auschwitz concentration camps. The trials began on 17th September and will probably continue for some time, as progress is slow owing to the necessity for translating the whole procedure into so many languages.

Three of us set out from Belsen at 7.30 am on 1st October in the UNRRA station wagon, each provided with a thermos of tea and sandwiches. It was rather dull when we left, but soon the day turned to one of autumn crispness and warm sunshine. The countryside was lovely—the trees are turning crimson and gold and for long distances meet in an archway overhead.

We arrived in Luneberg at 9 am, parked the wagon and walked across to the British Military Court House, which was barricaded off and guarded by armed British sentries in their red caps. Our official passes appeared to satisfy them and we were allowed to pass on to the main entrance, where they again produced the open sesame. We were shown into very good seats behind the witness box and had time to survey the court before the day’s session opened.

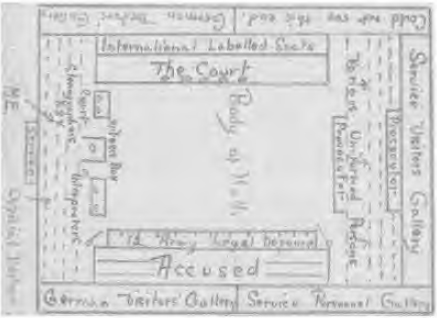

This rough diagram will give you some idea of the positions:

German carpenters had converted a gymnasium into a courthouse to hold 250 of the public as well as the officials. The public gallery facing the accused was crowded with Germans who were listening to the revelations of the Concentration Camps with rapt attention. This gallery was closed in with wire netting. Some of these people, although Germans, had suffered under the Hitler regime. All Germans were searched before they entered the court and pocket knives, etc., removed in case they attempt to pass them for the prisoners to commit suicide. The German press was represented by nine men and I believe news of the trials is being given over the Hamburg Radio.

Seated in three-tiered rows, with the most notorious in the front, the prisoners were guarded by men and women of the British Military Police. There were forty-five prisoners in the dock, twenty-six men and nineteen women. I think three others on trial were ill and did not attend, because I saw one wearing No. 48. They were dressed either in old SS uniforms without badges or as civilians, and were the most menacing and degenerate-looking lot of human beings I’ve ever seen together. Obviously with a poor mental development. They filed in, some smirking, others stolid and sullen, and took their seats. Large black numbers on a white background were sewn on the backs of their garments and on cardboard hung round their necks in front. It is said that each of these accused is responsible for at least 1000 murders.

No. 1 was Kramer, the Beast of Belsen, a grim, thin-lipped heavy creature with narrowly set eyes, low and receding forehead and dark hair. He showed no emotion during the trial but scribbled notes from time to time.

No. 2, Dr Klein, sat next to Kramer and was a more wiry type with a head which appeared to have been squashed up on both sides and surmounted with tufted greying hair. He was the Mad Doctor of Belsen and described the place as a camp of death, I believe.

No. 9, 21-year-old Irma Grese, looked rather defiant, a pert young thing with eyes of steel, very little chin and a straight, small, hard, cruel mouth. She appeared amused at the proceedings and admitted that she had used whips made of tough, transparent, twisted paper on helpless women.

No. 6, Juana Bormann, was the woman who had the savage dog which, when she let it loose on the prisoners, tore them to pieces. She was a wicked-looking witch and religious fanatic about forty years old, small, thin and sallow, or rather, prune-coloured.

Elizabeth Volkenrath, whom I think was No. 11 but am not quite sure, is about twenty-six years old and is alleged to have beaten seven people to death with a truncheon—she was known as the Jew Gasser.

One would imagine that all these prisoners must have been mentally unstable in some way. They say many of the SS were chosen from the bullies and degenerates at school. The men looked like some of the worst characters from the Rogues Gallery at Madame Tussauds—many of the women had small square chins and little hard mouths and assumed an insolent attitude. Irma Grese had worked in concentration camps since she was seventeen and said she liked it. It was an experience, and it will be interesting to see the result of the trial. I believe Kramer was in the box yesterday, the 9th October 1945, and his wife and Dr Klein today. The defence those ‘innocents’ put up is amazing, but Dr Klein let Kramer down today—so there is apparently no honour among thieves when their necks are in the noose. I took notes at the trial but am afraid I may not have got all the names correctly spelt.

The day I was there at 9.10 am, after an announcement was made in English and German that all were to be seated within the next ten minutes, the prisoners filed in at 9.20 am. All persons were seated and were instructed to keep their hats on until the Court entered. Punctually, the Court entered and we stood until the President, Major General H. P. M. Bernay-Ficklin CB, MC, crisply instructed all to be reseated.

A civilian member of the Judge Advocate-General’s Branch, Mr C. L. Stirling, gave the court expert advice on all legal points. The first witness was a Rumanian doctor, Sigismund Charles Bendel, who gave his evidence in French and who was excellent and could not be shaken. He looked a worn and broken man and had come from Paris for the trial; he was arrested by the Nazis because he was not wearing the compulsory Jewish Star. The interpreting was excellent. The Prosecutor, Colonel T. M. Backhouse, an English Barrister and Field Marshall Sir Bernard Montgomery’s Assistant Judge Advocate-General, put the questions in English, they were translated into French, the doctor replied in French, which was in turn translated to English for the Court and German and Polish for the accused. This is the story he told:

On 10th December 1943, Dr Bendel was sent to Auschwitz concentration Camp in Poland and at first was forced to work as a stone mason and later as a doctor to a Gypsy camp of 11 000, where he saw injections causing instantaneous death given as experiments to men, women and children. By July 1944, 4300 of these prisoners had gone to the Crematorium, and except for a working party of 1500, all others had died.

In June 1944, he stated, an SS doctor had ‘given him the honour’ by attaching him to the Crematorium. He was asked if he worked in the crematorium and stated that he and 900 other deported persons called the Special Kommando were forced to work there. There were also Senior Kommandos who were given special privileges and who lived completely separate from the other SS guards. There were about fifteen of these special men, three for each crematorium.

The DP special Kommandos were locked in special Blocks when not working and were not allowed to leave. The German SS guards were relieved by other German SS men. There were four crematoria, each equipped with two gas chambers, at Auschwitz. The witness lived first as a DP in camp and then at the crematorium itself In August 1944, on his first day, 150 political prisoners, Russians and Poles, were led out one by one and shot, but no one was cremated. Two days later he saw the crematorium working. He was on day duty (there was a night shift also). In the Ghetto were 80 000 people. At 7 am the white smoke was still rising from the last of those who had been incinerated during the night.

This method was much too slow for the numbers to be cremated, so three large trenches about 17 x 6 yards were dug and the bodies were finished off with wood fires, saturated with petrol. This also was too slow, so canals were built in the centre of the trenches into which the human fat dropped and burning was hastened. Dr Bendel said the capacity of the trenches was almost fantastic. Where No. 4 crematorium had been able to burn 1000 persons daily, the trenches were able to cope with this number in one hour.

Transports were arriving with between 800 to 1000 people daily. Those too ill to walk would be in tip-trucks, from which, to the amusement of the drivers, they were spilled without warning.

He was asked by the prosecutor to describe a day’s work. His description is as follows:

At 11 am the chief of the political Department arrived on a motor bike to announce that a new transport was expected. The trenches had to be prepared, cleaned out, and wood for burning and petrol put in. At 12 midday the new transports arrived, 800 to 1000 people, who were undressed in the courtyard and promised a bath followed by hot coffee. They were ordered to put their clothes on one side and valuables on the other. They entered a big hall where they had to wait until the gas arrived. In winter they undressed in this hall. Five to ten minutes later the gas arrived in a Red Cross ambulance, the strongest insult to a Doctor and the Red Cross.

The doors of the two gas chambers were opened and the people sent in-terribly crowded. One had the impression that the roof was falling on their heads, the ceiling was so low. Forced in by blows from whips and sticks, they were not allowed to retreat—when they realised that it was death which they were facing they tried to return to the hall, but the SS guards finally succeeded in locking the doors. There were cries, shouts, fighting, kicking on the walls for two minutes, then nothing more.

This moment in the court was tense, the doctor spoke so quietly but with such dignity and conviction that we were all aghast at what we knew was the stark and awful truth.

Five minutes later the doors were opened but it was impossible to go near the gas chamber. Twenty minutes later the special Kommandos started to work. Doors were opened, bodies fell out, quite contracted—it was impossible to separate one from the other. One gained the impression that they had fought terribly against death. Anyone who has seen a gas chamber filled to a height of four feet with corpses will never forget it. At this moment the special Kommandos stopped. They then took out the bodies, still warm, covered with blood and excrement. Before being thrown into the ditches they passed into the hands of the barber and the dentist. The hair was used by the Germans to make material. The teeth contained much precious metal and also did not burn easily.

Now proper hell is started. The Kommandos are told to work as fast as possible—they try to drag the corpses by the wrists in furious haste-they worked like devils, they were no longer like human beings as they dragged the corpses away under a rain of blows. A barrister from Salonika, an electrical engineer from Budapest. Three to six SS men gave blows from rubber truncheons and continued to shoot people in front of the trenches, people who could not be put into the gas chambers because they were so overcrowded. After an hour and a half the work was done. The newest transport had been dealt with in crematorium No. 4.

Asked who had been the commandant at Auschwitz at the time, Dr Bendel quickly replied, ‘Kramer. Commandant Kramer was in charge at this camp and was seen at the crematorium several times and was present at the killings.’ (I have since been told that he used to gloat over this.) On one occasion a man who worked at the crematorium tried to escape, was brought back and killed. SS doctors were seen at the crematoria, and one Dr Klein (in court) was seen in the ambulance which brought the gas, sitting next to the driver.

On 7th October 1944, 300 special DP Kommandos were told they were to work elsewhere, but they knew they were going to their death. That day 500 people (400 in Crematorium No. 3 and one hundred in Crematorium No. 1) were killed. The DP Kommandos were killed in No. 3. They were called one by one, undressed naked, put in rows of five, and an SS man passed by and shot them in the neck.

As a doctor, the witness had to attend to any of the Kommandos if they had an accident, such as burning human fat on their feet.

‘In December 1944,’ he continued, ‘at Auschwitz four women were hanged in the women’s compound for passing dynamite to a doctor for the purpose of exploding the camp—the girls worked in a munitions factory and were publicly hanged without trial. Hoessler ordered the hanging.’ The witness was asked to identify anyone and he picked out Kramer and Dr Klein. He had never seen Hoessler, who was also present, he said.

The senior doctor at Auschwitz, a Dr Mengele, carried out human experiments, but no DPs took part in any of these. H. P. Feuhrer Moll gave the orders and Moll was responsible to Kramer, who received his instructions from the Political Department of which Himmler was chief.

On 7th October 1944, crematorium No. 3 was set on fire by the DPs there, 500 people took part in the revolt, but owing to some confusion and misunderstanding they could not reach their firearms.

The Court adjourned at 11.40 am for ten minutes. At 12 noon the second witness was sworn in: a Jew from Lodz, Poland, Romason Polanski by name (not sure of spelling). He was arrested in 1939 because he was a Jew, and was in a number of camps including Auschwitz in the autumn, 1943. When the Russians were advancing in the east, he was removed to Belsen. He was asked to identify any of the accused, who were floodlit for the purpose. He identified Kramer, Hoessler, Schlamontz, and a Pole named Ambon. ‘My good friend,’ as he put it and whose name he did not know but who was in the stores at Belsen.

Asked what Kramer had done, he stated that three days before the liberation of Belsen, witness went to the cookhouse and there were rotten potatoes lying on the ground. He started picking these up (they had been starving, you will remember), when Kramer shot his two friends dead and wounded him in the hand. He passed round the court and he exhibited the wound. Asked about the man in the stores he said he had led the men who had dragged the corpses to the graves and beat people with rifle butts and shot them when too exhausted to work. He also bit and kicked them. He hid himself and shot the starving prisoners as they tried to find food. They were all killed as he was only two or three metres away.

Hoessler, he said, was Commandant of No. 1 Crematorium at Auschwitz. In 1943, on their arrival at the railway station, Hoessler approached and formed them in fives. The witness said he tried to stay with his two brothers, but Hoessler sent them to the crematorium. He (the witness) worked there himself later, employed in cleaning the gas chambers and loading dead bodies onto lorries.

The Court adjourned at 1.15 pm and resumed at 2.30 pm. During this interval we sat in the station wagon and ate our lunch.

The previous witness again entered the box for a brief period and then the third witness appeared: Anita Loske, a German Jewess of Breslau, imprisoned in Auschwitz, December 1943, as a political prisoner. She actually saw selections being made by Hoessler and Dr Klein of hospital patients destined for the gas chamber. She said people were lined up at these selections and marched by—those who were to live were put on one side, those destined for the gas chamber on the other. This girl was a member of the Band which played at these selections and at public hangings in the camp. She was later transferred to Belsen.

Some days before the British arrived, Red Cross armbands were issued to workers by Dr Klein and they were told to be kind, etc. The approach of the British also affected the SS women, who pretended to be interested in the prisoners’ welfare. Prisoners were told to be very strong because they were to be liberated soon. Previously these women, including Irma Grese, had carried whips and treated them very badly.

Three days before the arrival of the British all prisoners were assembled by Kramer and told to start digging graves, into which they had to drag the bodies. She identified Kramer, Dr Klein, Hoessler, Grese and others, and when she had finished giving evidence, stood for fully three minutes, just looking at them in silence. What a moment of triumph! She said later that the existence of the gas chambers was well known.

In answer to a question, she said the Hungarians came to Auschwitz Camp in May 1944. There were queues waiting day and night for cremation as there were so many people. She was taken to Belsen in November 1944, when there were very few people there and no huts; they lived in tents. Conditions were bad; it was winter, they were sick and had to wash outside in the cold and rain. The SS beat the inmates to keep order. Kramer arrived at Belsen about December 1944, and conditions became worse-beatings and other cruelties were introduced. There was no orchestra at Belsen. She was beaten with wooden sticks in Belsen for being late.

The fourth witness came in at 4 pm, but before she entered, all numbers were removed from the prisoners and No. 22 was allowed to change his place to wherever he liked.

The fourth witness was a girl of twenty-one, a Polish Jewess from Warsaw, arrested in April 1943 and sent to Auschwitz for sixteen or seventeen months, and to Belsen in July or August 1944. In Auschwitz her mother was with her, but was taken to the bathroom, beaten by SS women with a stick and issued with prison clothes, but she knew she was destined for the gas chamber. She was asked to identify the women who had done this. No. 6 she said was one, and that everyone was frightened of her as she kept a savage dog. No. 7 was women’s Camp Commander at Belsen and very cruel. No. 9, Irma Grese, carried and used a whip and also shot people. No. 10 was another. No. 11 collaborated with the SS in Camp No. 40, ill-treating hungry people, beating them kneeling down, etc., in winter. No. 48 was a notorious collaborator with the SS—everyone was frightened of her. And so on. No emotion was seen on these sadistic women’s faces during this identification. Witness No. 5, a Polish Jew, entered the box at 4.30 pm. He was arrested in 1941. He recognised No. 19 as being in charge of the transport which brought him from Dora Camp to Belsen. He had also been in Buchenwald. They had no food or water on the journey and when witness asked for the latter he was told he would get it with this pistol. The journey took seven days. More than fifty per cent died, bodies were left in the wagon on arrival at Belsen. No. 19 was walking along the train and was asked for water, which he refused. His attention was drawn to the bodies taking up space. It was suggested that they be thrown away, but he said that the others were going to die anyway so what was the difference. On arrival at Belsen they lay in the open and were beaten with iron bars. The witness’ friend ended up in bed as a result of these beatings. The only reason for this treatment was that they were Jews. His friend died.

The accused was grinning during this evidence, and did not appear to attach any seriousness to it. I believe the accused prisoners are confined in the town jail, where two share a room fitted with running water and mirrors for the women. Their diet consists of a daily ration of one thick slice of German bread for breakfast, one litre of soup at midday, another slice of bread with corned meat and about half an ounce of margarine for supper. With each meal they receive a small can of ersatz coffee.

On 18th September Brigadier H. L. Glyn Hughes, the first witness in the trials, said, ‘I have seen all the horrors of war, but I have never seen anything to touch Belsen.’ He said that the expectancy of life for a person in reasonable health interned in Belsen Camp was no more than three months. When he toured the camp with the camp doctor, Klein, the latter appeared quite callous and indifferent.

Colonel Backhouse, who opened the prosecution, was frequently compelled to admit that no words could describe the horrible things which had occurred-and said before the Nazis came, mankind had no need of words to speak of such things. He said the women guards had found sport in setting wolf-hounds to tear living people apart. He also stated that the real horror was not the things he had been describing, but the fact that there existed in the German mind determination to inflict these horrors on fellow human beings.

The charge against all defendants is ‘At Bergen-Belsen Germany, between 1st October 1942, and 30th April 1945, in violation of the law and usage of war, they were together concerned as parties to the ill treatment of certain persons, causing their deaths.’ Thirteen Allied nationals who died are named, including a former member of the Royal Navy, Keith Meyer. The second charge against Kramer and eleven others is a similar charge concerning Auschwitz Concentration Camp, Poland.

Harold le Deuillence, the British survivor of Belsen, said he was having his first meal for five days when the British cam e—he was eating grass.

The Court adjourned at 5 pm and we had a comfortable drive back. That these men are given British justice is too fantastic and I’m sure they do not appreciate the privilege. I don’t know how the twelve men for the defence can possibly do it, but, of course, they must, if selected, as they are all British army officials, except one Polish Lieutenant who is defending four of the Poles among the accused. Major T. C. M. Winwood defended Kramer, who with the other accused refused an opportunity to have German civilian counsel, whom they would have had to pay.

Well, my friends, this ghastly letter has been written in two sessions and is, I am afraid, rather disjointed, but will give you a first-hand picture of what a Totalitarian Dictatorship means for the world.