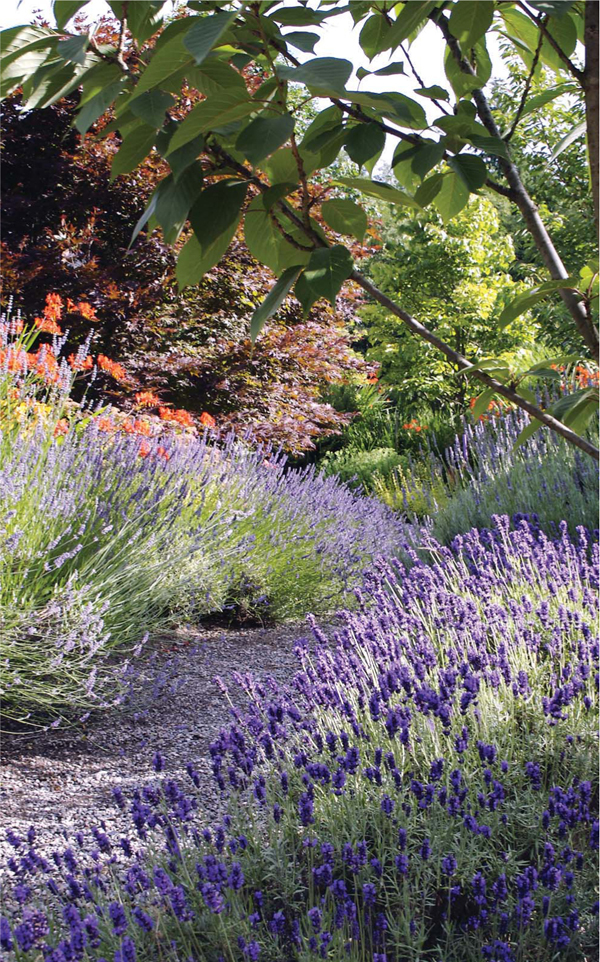

Sam the cat basks amid the relaxing fragrance of Ruth Flounder’s herb garden. Informal hedges are a popular use of lavender.

Sam the cat basks amid the relaxing fragrance of Ruth Flounder’s herb garden. Informal hedges are a popular use of lavender.

Lavender in the Garden

Lavender is rather new to kitchens in the United States, and many folks are still reluctant to try it. It was in the fine French restaurant L’Absinthe in Manhattan that I was first treated to a lavender sorbet atop a paper-thin openfaced apple tart. The chef explained that in the south of France, where he was raised, lavender was commonly used in cooking.

Surprise visitors to your kitchen herb garden by planting one of the sweet lavenders (Lavender angustifolia) among the basil, thyme, oregano, lovage, borage, and coriander. After you explain that lavender is in the same family as mint and is closely related to rosemary and thyme, the concept will make sense, even to those who don’t have a green thumb.

Once the lavender is planted in the kitchen herb bed, the next step is to incorporate it into your cooking. Some people are hesitant to try something flavored with lavender, because the idea seems too outlandish. I wait to announce to my guests that a recipe contains lavender until after I’ve received compliments on the delicate and unusual flavoring of a dish.

For years I stubbornly ignored the sage advice to plant cooking herbs as close to the kitchen door as sun and space allow. Instead all my herbs were planted in my raised beds 500 feet from the kitchen. At suppertime, when the fish needed a few sprigs of dill or the chicken cried out for fresh rosemary, I fought with myself to make that long trip out to the garden. Often my lazy side won out, and it was garlic again or, worse yet, a miserable sprinkling of some dried herbs I’ve had in my spice drawer for years, with a label from a supermarket long since bought out by another chain. I realize this is a shocking confession from someone in the flower and herb business, but it’s true.

I’ve since seen the light and have reformed my ways, and now I have just enough plants near my kitchen for regular daily use. Even after the lavender has been harvested in early July for all my drying needs, there are sprigs pushing forth in a sparse second bloom, certainly enough to add to a fresh fruit dessert or sprinkle in my stew pot. Well into November, even after several light frosts, I can pick enough cooking lavender to flavor the pot.

Don’t hesitate to put your cooking herbs in any sunny, convenient location, tucked here and there in your annual bed or perennial border or planted in containers. A few plants of your favorite herbs are all you need to perk up your meals. If you prefer to plant a formal kitchen herb garden, see the discussion below on knot gardens.

Jardin du Soleil features a charming herb garden with lavenders and cone flower, as well as sage, Santolina, lamb’s ear and others not shown here.

Throughout history, the garden was often a metaphor for healing of the mind and spirit, as well as the body. It contained important herbs, such as foxglove for heart problems, poppy for killing pain, chamomile for sleep and relaxation, hyssop for coughs and chest ailments, and garlic, chives, and other alliums for purifying the blood. Lavender was planted for its antiseptic, carminative, and relaxation properties.

When planting an herb garden of medicinal plants, accurate labeling is extremely helpful to visitors, not just the common and botanical names, but an indication of the historical uses and which parts of the plant, such as root, leaves, flower, seeds, pods, or sap, were used, as well as what kind of preparation: a tea or infusion, salve, poultice, or plaster.

Again, some herbs can be dangerous if continuously used. “Natural” or “organic” are not synonymous with “safe”. It’s important to learn about the effects of the herbs you grow for consumption or to ask a qualified herbalist before dosing yourself from the garden.

A formal herbal knot garden or a foursquare geometric garden is a thing of beauty, admired especially by those who do not have the temperament for carefully plotting, trimming, and manicuring. In a knot garden, the herbs that weave in and out seem to have no beginning and no end, forming a botanical expression of infinity like those used in Roman, Islamic, and medieval Christian cloistered gardens. The knot garden became increasingly popular during the Renaissance in England, along with larger planting of hedges in maze form. The knot garden not only is lovely to view while strolling but also is an intriguing sight from a window or balcony above. One of the dwarf hardy lavenders like ‘Munstead’ is particularly useful as a low hedge in a knot garden, a more fragrant and interesting alternative to boxwood or germander. The gray-green leaves add a subtle hint of color both before and after the bloom period, and the humming of the bees attracted to the flowers adds an aural note.

In foursquare gardens, plantings are done in four squares or rectangles, with brick or gravel walkways forming a cross separating the squares and a focal point like a fountain, statue, or sundial in the center. A low hedge borders each of the quadrants. Dwarf lavender is a lovely plant for the edging, or one of the taller angustifolias or intermedias can be used for the center of the square.

The formal knot garden at Well-Sweep Herb Farm includes sheared plantings of lavender, germander, dwarf hyssop, and ‘Red Pigmy’ barberry.

Problems inevitably arise when one of the plants in such a garden dies. Running to the nursery to buy a new plant is hardly the answer; the replacement always looks just like what it is—a poor substitute for the original. It’s very hard to find fully-grown replacements to fill in a hole in a seven-yearold hedge.

One serious gardener I know solves this problem by always starting with more plants than she needs. She plants the extra herbs in a specially prepared waiting bed off to one side of the garden and behind some shrubbery. When the need arises, usually several years after the patterned garden is planted, she has understudies of the same age, size, and variety ready to make their way onto the main stage.

Fragrance and Other Sensory Enhancements for the Garden

I had just moved into an 1830s stone farmhouse when I first happened upon the notion of a fragrance garden planted beneath a window. The idea was that the mingled perfumes of the garden bed would waft into the house through the open window. I was a novice gardener, and I planted heirloom peonies, fragrant iris, lavender, mock orange, and phlox, dreaming of future pleasures.

The original windows of my home, with their rippled glass windowpanes, have no sash mechanisms to hold up the heavy frames. Once the windows are raised, they must be propped up with dowel sticks, which I’d painted to match each room. Though the 22-inch-thick stone walls provide wonderful insulation on a hot summer day, they also make the windowsills 20 inches deep. To get the proper leverage to raise the windows, I had to hop up on the sills and raise straight up—not the most convenient activity. Where I lived in northeastern Pennsylvania, most of the windows get propped up in June and closed in October. The peonies, iris, and mock orange had long since finished their bloom before the windows were opened so that I could enjoy the fragrance. The lesson to be learned: Pay attention to bloom time. Select plants with a sequence of bloom that you can enjoy many months.

Plant a fragrance garden where you will enjoy the benefits: late-spring- and summerblooming plants around a patio, earlier fragrant plants on a path or at the entranceway, where you can enjoy the perfume coming and going. Plant creeping thyme between the flagstones that you tread upon entering and leaving your home. Include a bed of narcissus varieties and hyacinths early in the season, some lavenders like L. angustifolia or L. x intermedia, lily of the valley, a well-behaved mint like mountain mint (Pycnanthemum pilosum), summer lilies like rubrum, scented geraniums or lemon verbena, a fragrant heliotrope, peonies, bee balm, roses, and for late appeal, sweet Annie (Artemisia annua).

This fourteen year old lavender ‘Hidcote’ is a wonderful companion to the ‘Royal Bonica’ rose.

A plot in the community garden on Roosevelt Island in New York City combines the gardener’s treasured favorites.

Modern cultivars of certain traditionally sweet-smelling flowers such as peonies, roses, and sweet peas have been bred for characteristics like disease resistance, size, and color, to the detriment of aroma. When ordering from a catalog or buying from a nursery when plants are not in bloom, make sure that the advertising copy or label includes a notation about the aroma, or you will be in for an unhappy surprise: visual beauty without the characteristic scent.

Enhance the sensory theme of your fragrance garden by including plants specifically for texture, like the velvety lamb’s ear and the surprisingly dry strawflower. Podded flowers like annual poppy, okra, nigella, and martynia add interest to a textural garden. Also consider sounds in the garden. Where scents are most powerful, the humming of bees will be evident. Add a simple water fountain or bubbling pump for pleasant, soothing sounds.

Whether bordering a formal herb design, a path to the front door, or a walkway leading into an outdoor garden room, lavender hedges are a traditional way of leading a visitor down the garden path. Because of the nature of its woody stems, lavender is more like a small shrub than a perennial, with the added advantage that the leaves remain on the plant during the winter. Some gardeners like to clip and trim the branches to a more regular shape; others allow the plants to sprawl, hanging over the path, where stray shoots get trodden on, releasing the most delightful odor.

In Manhattan, a vest-pocket park features impeccable hedges of lavender and boxwood, with accents of purple petunias and silver Artemisia.

Butterflies love a jumble of colorful flowers, particularly tubular ones like lavender. They seem to be attracted to profusion, so if you want a butterfly garden, plant masses of flowers together.

Butterflies lay their eggs on specific host plants, which the hatched caterpillars use for food. Though lavender is not a major host plant, its nectar attracts butterflies, and since butterflies spread their wings in summer, the later blooming lavenders are perfect for northern gardens. Remember that pesticides are often fatal to butterflies, and herbicides cut down on many of the native habitats that butterflies seem to prefer.

The imposing Madrid Archeology Museum in Spain is densely planted with lavender and gray Santolina.

The lavender border at Well-Sweep Herb Farm displays a broad sampling of the cultivars they sell. The angustifolias were blooming in mid-June; the intermedias will bloom about a month later.

Lavender takes its place in a perennial border or mixed bed of perennials, annuals, and shrubs as much for its habit and foliage as for the flowers. Since the foliage stays on year-round, there is some presence in the border from the earliest days of spring through the following winter. The often grayish hue complements the hottest fuchsia or orange as well as pastel pinks, blues, and yellows. Even if you pick the flower spikes to use indoors, the plant still looks interesting for most of the year.

Because healthy lavender needs good air circulation as well as full sun, leave some room for the plants to spread; the larger lavenders may grow 5 feet across and don’t enjoy crowding.

Lavender in its native range, along the dry, rocky Mediterranean coast, grew in hot sun, poor soil with good drainage, and drought conditions. Rock gardens as they are designed in the United States resemble such habitat. They are usually located on steep embankments where the soil is shallow and the drainage excellent. Because of the slope, lavender plants are naturals for a south-facing rock garden. They are semi-drought tolerant and crave sunshine, and the protection of the slope will help ensure a long, happy life in horticultural zones 5 to 9.

Coral bells and lavender (bottom) were selected by two home gardeners with bright golden foliage (top) and in a mixed border of mostly pastels.

The path at Frog Rock Lavender leads you into the farm on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

A rock garden that pleases the eye repeats creeping and mounding forms, as well as colors, along its expanse, so it’s good to use a number of plants of the same variety here and there throughout the garden.

Traveling through Spain with lavender on my mind, I expected to see purple drifts of Spanish lavender, growing wild on the hillside and planted in farmers’ fields. They may well be there, but in two weeks of traveling I sighted none. Instead, lavender was used in com mercial landscaping, from the few rocky beds surrounding a car rental lot in the Granada airport to mixed beds of L. dentata in front of an office building on a fashionable street in Madrid. The most impressive sight was the use of lavender in planters on the balconies of an insurance building on a bustling Madrid street. As seen by passersby on the ground, the purple haze repeated on all seven stories and on all four sides. The countless flower spikes were reflected into the mirrored facade, where they mingled with the reflections of the clouds above.

In years gone by, I planted tender lavender species in my zone 5 flower border, watched them grow and bloom, and mourned their death with the first killing frost, around the middle of October. Then I learned better and planted my L. dentata and L. stoechas in terra-cotta pots that sat on my patio near an old well pump from May to October. Their winter home was my sun porch, with a bright eastern exposure and skylights, where they flourished for the next six months, some blooming their fool heads off and some sending out the occasional bloom, which was cherished all the more when a heavy frost or dusting of snow coated the meadow just beyond the patio. The flowers were much paler indoors than out, almost white.

Lavender dentata spends Pennsylvania winters on the sun porch to avoid the icy weather (left). Taken out again in spring it will survive many years; tender lavenders can also be treated as annuals (right).

‘Hidcote’ lavender is planted with nemisia and osteospurmum in a big tub. Five-year-old hardy lavenders on my rooftop in Manhattan survive the winters in containers with no special care.

It is best to plant your tender varieties directly in containers, to avoid transplant shock every fall and spring, but if you haven’t thought of that in time and still want to winter over indoors, you can dig the plants in late summer and transplant them into pots 2 to 3 inches wider than the root balls. Water well and leave outside for at least two weeks. Bring the pots indoors to their winter location before the heat goes on in the house, to reduce the additional shock of a drastic change in atmosphere. Though the plants might prefer 40- to 50-degree temperatures at night and 60 degrees during the day, most people don’t have a separate conservatory in which to pamper their lavenders. I consider them part of the family and treat them like everyone else, with temperatures at 62 during the day, 60 at night, and 68 if I’m sitting still for a long time reading or playing bridge. Water your container-grown lavenders when the top of the soil is dry to the touch, and use your favorite plant fertilizer about every three weeks.

I gave up my farm and moved to Manhattan, smack in the middle of New York City. Our condo in a medium-size building of 100 apartments has no balcony, terrace, or even a fire escape on which to grow plants illegally. But the building has a 70 by 100 foot roof garden on the eighteenth floor, and I volunteered to be a one-person garden committee, with the condo association picking up the tab for all plants, containers, and soil. At first disappointed that no one else offered to work with me, now I’m grateful. I can select my favorites and experiment with any plants I want, with no one else to say me nay. I pore over seed catalogs as always, start seed on a windowsill, even compost in containers on the roof. At the current count I have seventy-nine containers: three for trees as large as 42 inches across, and most on a drip irrigation system.

Cuttings from the tender ‘Goodwin Creek Grey’ rooting on the windowsill of my office in winter, while the mother plant hangs out at the far right.

The oldest lavenders are now five years old, ‘Hidcote’, ‘Grosso’, ‘Provence’ and my latest, the tender ‘Goodwin Creek Grey’ that I’ll winter over in my apartment. Altogether I have sixteen lavenders throughout the garden, sometimes attracting butterflies fluttering their way above street noise and traffic to my garden oasis in the sky.

Outdoors in late spring and summer, you can mix the plantings in the container with colorful annuals like pansies or dwarf lemon yellow marigolds. When the summer heat gets to be too much for the pansies, replace them with a delicate verbena or trailing nasturtium. Or plant one container full of lavender and other containers each filled with other types of plants. You can rearrange the pots as they come into their best bloom seasons. To winter over in zone 5 the container should be at least 15 inches in diameter, so the roots don’t freeze. Don’t mix lavender in a container with a water-loving plant like hydrangea, as their opposite requirements might make you frantic.

The ability to plant lavender in containers means that those who have small spaces can enjoy this species on a terrace or patio or in a tiny yard and move the containers to better advantage throughout the season. Remember, though, that lavender always needs excellent drainage and full sun, whether in the ground or in a pot.

With careful pruning and shaping, lavender can be trained into a potted standard the same way as the more typical rosemary. Choose a hardy variety with a straight, woody center stem, and prune all other stems off the plant. As the plant continues to grow, cut out all side branches but allow the top to branch out. When the plant has reached the height you want, nip off the tip to encourage a more bushy habit. You can shear the leaves to a geometric form or let the plant grow naturally to allow it to bloom.

As with any lavender, good drainage is essential. Water when the soil is dry to the touch, fertilize minimally, and provide plenty of sunlight. If the trunk seems to be wandering off course as it grows, tie it to a small stake to train it upright. If you prefer a more natural, gnarled look, you can leave it unstaked, as a larger version of a traditional bonsai.

This potted plant will take several years to attain its full growth. You may keep it in a sunny area indoors year-round or let it summer on a patio or terrace and winter inside, to protect the roots from the cold. When I have a particularly lovely plant growing contentedly indoors, I use it for special occasions, such as a buffet centerpiece for a party.

One spring, when I went to prune one of my old angustifolias, I found that the woody stem had become so bent and twisted that it reminded me of a cedar on a windswept coast. There was little top growth, and the plant looked like it might not make it another year. I dutifully pruned about one-fourth of the leaves and made a mental note to start a bonsai if this plant made it through the summer.

In August, the plant had grown and bloomed, and I was ready for my experiment. I lined a shallow bowl with plastic, and put down a layer of gravel and then some sandy soil. With a sharp pair of clippers, I pruned off most of the branching stems and top growth and clipped out much of the root structure as well. As with any bonsai, when pruning the roots to fit the shallow pot, you must keep a balance between root growth and top growth. The plant must not be top-heavy. Enough roots are needed to provide nourishment to whatever leaves (and flowers) you keep.

I planted the pruned lavender in the pot and put it in a sunny window, watering when dry and fertilizing lightly. After several weeks, all the old leaves had died back and new growth was sprouting from the woody stems. My elation was short-lived, however, as the plant died. My adventure over, I started a new bonsai with a young plant, following the recommended method so that the roots could adapt gradually to the restricted environment—a fine start for a young plant soon to grow into a classic bonsai.

A single lavender plant makes little impact in the garden, as the blue-violet color of the flowers blends into the green foliage of other plants. The slender flower spikes are best viewed en masse. An older, well-pruned plant may make an impression, but it’s most common to see lavenders planted in hedges or groups.

Here the lavender takes a backseat to the splashy gold coreopsis.

When combining lavenders with other plants in the garden, think of both the lavender flower and the foliage. Spring bulbs look wonderful with a backing of perennial lavender foliage. When other perennials are just starting to push their leaves aboveground, the gray, needlelike leaves of lavenders are already starting to put on a real show.

For a blue, purple, and silver garden, plant lavender with perilla and purple basils, globe thistle, verbenas, blue larkspur and delphin ium, veronica speedwell, and a blue sage like ‘Blue Bedder’ or ‘Victoria’. Salvia argentea, a sage with large, velvety, silvery leaves, enhances the gray color of the lavender leaves. Try purple pansies in spring and asters to highlight the second lavender bloom in late fall. Mix in white phlox or midsummer white lilies for contrast.

Combinations of lavender and pink are common, lavender and yellow less so. A gardener near me plants her lavender against goldenthread false cypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera c.v. Filifera aurea), and a designer at Longwood Gardens, in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, chose a similar theme of lavender against dyer’s woad (Isatis tinctoria). I like to plant it with brilliant gold-orange heliopsis, golden yarrow, and globe centaurea.

Downy lavender (L. multifida), an annual in my garden, doesn’t usually bloom until late July or August. By then the 3-foot-high spikes look great in combination with brilliant zinnias, never too ordinary for me to love.

When planning lavender combinations, consider when the flowers bloom in your area and how long the blooms last. If you are going to cut off the spikes for drying as soon as they begin to open, however, consider combinations of foliage rather than bloom sequences.

Lavender and violas are beautiful together. Later, incorporate animals or place pots of color directly in the garden if bloom is important.

Even though the mogul emperor of India, Shah Jahan, had a garden of white flowers and gray foliage planted in 1639 near Delhi, and perhaps others were planted even before that, the modern reference for a moon garden is the restored garden at Sissinghurst, England, planted by Vita Sackville-West. That garden welcomes thousands of visitors a year, who are intrigued by the lovely bright white and gray plantings, shown to best advantage after dusk. The flowers reflect the moon’s glow on summer evenings, and the pristine whiteness shimmers on romantic evening strolls through the garden.

A moon garden is planted both for light and for fragrance, with narcissus, lilies, phlox, nicotiana, jasmine, and gardenias perfuming the air for the visitor. White lavender is often included because of its gray foliage that is perfect for a white theme garden.

To start a moon garden, select one bed or area of the garden, and choose plants that have white blooms and foliage that is white variegated or gray. The gray color comes from the reflection of little hairs on the surface of the leaf and usually indicates that the plant is drought-tolerant, as the hairs protect the leaf from water depletion in the hot sun.

Decide whether you want to carry the white theme year-round or only in the summer. To enjoy a moon garden, plant it where you will sit on a summer evening, where you will stroll, or lacking time to do either, where you will stride in the evening to and from your home.

The plant lists for a white garden are endless, and it’s fun to pore over the catalogs in midwinter and make your plans. Appropriate plants come in a variety of habits and species, including shrubs, climbers, annuals, and perennials.

Shrubs and Climbers

• Variegated lily-of-the-valley shrub, which has lovely green and white waxy foliage and drooping white panicles in May and June.

• A white rose like ‘Fair Bianca’, which has the form and scent of an old rose and has a second bloom.

• Gardenia, if appropriate to your planting zone.

• Hydrangea like ‘Pee Gee’ or the climbing hydrangea, both of which have large, dramatic blooms.

• Moonflower vine, an annual with huge, white, morning glory–like blooms that unfurl in the evening and die at dawn.

Perennials

• White lavenders are L. x intermedia ‘Dutch white’, L. a. ‘Alba’, a white lavender, or L. a. ‘Nana Alba’, a dwarf white. Select by plant height and hardiness, and ask your favorite herb source for other recommendations.

• Lamb’s ear, that velvety gray perennial.

• The bright, woolly ‘Silver Sage’ with its large, showy leaves.

• Babies’ breath, which has a cloudy delicacy and never looks trite in the garden.

• White phlox, like the disease resistant ‘Miss Lingard’.

• One of the gray-white artemesias like the annual dusty miller or the perennials ‘Silver King’ or ‘Silver Mound’.

• Gooseneck loosestrife, if you can plant it in a contained area, as it is an invasive but lovely summer bloomer.

Annuals

You may need to plant annuals from seed to get white selections, but look for “white” marigolds, ‘zenith hybrid’ zinnias, white snapdragons, nicotiana, cleome, cosmos, petunias, and alyssum. These will bloom all summer until frost and fill in your bed.