We start this chapter by asking whether there can there be collective, as opposed to individual, grace in human affairs (cf. Dear 2000, 263)? Why should anyone want to live in a City of Grace? Some, like monks and ascetics, are spiritually inclined, while the faithful could see mortal life leading to an afterlife. On a lower road, we might be seeking merely to parry the burgeoning demographics and compounding problems of neoliberalism. Having now established the dimensions of grace, a real-world and extended literary search for the city which embodies it can begin. Yet grace, as a quality bestowed, presumably cannot be either hurried or manufactured. Hence, in this chapter, we proceed in a measured way through the preliminaries, approaches, framework, precepts and strategies involved in modeling.

Preliminaries

Adopting Cartesian principles, it is important that all prior evidence bearing on grace, as in real-life places and supplementary urban literature, be fully explored. After this excursion, solid conceptual foundations can be laid for a working model.

Searching in the Real World

If grace is a worthy construct, the pragmatic route is to discover whether it already pertains anywhere in world urbanism. Could a City of Grace be found, by name or reputation?

In Australia, the Brisbane suburb of Graceville is well-heeled and amply supplied with eateries, but otherwise undistinguished. Less appetizingly, Gracemere, near Rockhampton in Queensland, boasts ‘the largest cattle saleyards in the southern hemisphere.’ Gracetown in Western Australia is a coastal resort claiming an immaculate right-hand surf break while, inland, Lake Grace is a serenely beautiful but empty saltpan playa. North America fares a little better. Apart from the suburb of Notre Dame de Grâce (NDG) in Montréal, Canada’s leading light is Gracefield, Québec, named after its original businessman, Patrick Grace, and home in 2011 to 2355 inhabitants. No US city over 100,000 in population has ‘grace’ in its name. Grace City ND in 2010 had 63 inhabitants: more substantial is Grace ID with an estimated 2016 count of 910.1 The late Elvis Presley’s 14-acre Graceland Mansion in Memphis TN is perhaps a little ostentatious. Alternatively, there are actually ‘cities of grace’ in Little Rock AR, Nashville and Murfreesboro TN, Canton and Columbus OH, Las Vegas ND and Sacramento CA,2 but they are individual churches, not entire cities. Overlooking other countries and error caused by nescience, this inquiry by name appears unprofitable.

Maybe the quest should identify religious sites since, according to Kostof (1992, 82), ‘whenever in any region of nuclear urbanism in the Old or New World we trace the characteristic urban form back to its origin, we arrive at a ceremonial centre.’ As temple cities, he cites: Olympia and Delphi in Greek antiquity; Mayan settings of Uxmal, Chicen Itza and Palenque; and, in Asia, Benares (India), Anuradhapura (Sri Lanka) and ‘the great landscapes’ of Angkor Thom (Cambodia), not overlooking Medina (‘the radiant city’) and Mecca in Saudi Arabia. This urban form has historically promoted a division between sacral and secular power. While, of the former, some monastic settlements continue to reflect theological and ascetic strands of grace, most are small, below the threshold of modern urbanism. Otherwise, over time, housing and other city functions congregated around an original shrine, separating church and state to the benefit of secularism in all but the most fundamental or theocratic regimes. Hence, ‘religion is now a matter of conscience, not law’ (Kostof 1992, 91). It might be that cathedral and other religiously inspired centers around the world have a head-start, but, as will be demonstrated, today they would need to meet some strict secular criteria to qualify as cities of grace. Their case should remain open pending further research.

A non-eponymous possibility could be Paris, appraised by David Harvey (2006). The City of Light, la ville-lumière, achieved renown as a center of learning and philosophy, along with its early adoption of street lighting. Many admire Paris’ architecture and form, enhanced through a decision after 1958 to validate the past by transposing modernist and postmodern additions to a new northwestern edge city of La Défense, now one of France’s key business centers. However, as the culmination of a difficult postwar settlement history (Sandercock 1998, 168–69), Paris has also been marred by endemic social and employment upheavals in which infrastructure and precincts have been torched. Its concorde might now be more of form than function: its claims to grace have receded.

Likewise, those of American cities: the view of Jan Morris (1987, 12), shared by the emeritus geographer James Vance, is that they had their ‘moment of grace’ in the 1950s. Johns (2004, 1–6) paints the scene. Before their industry and governance were ‘hollowed out’ by globalization and neoliberalism (Wadley 2008, 665), urban areas exhibited clear purpose, Adam Smith’s industriousness and sense of achievement. They hosted and nurtured homegrown businesses. Over the twentieth century, a rational consistency in city form developed. Districts had a distinct character, unbroken by elevated freeways, railways or massive urban redevelopment projects. With appropriate decorum, people left their vital, close-knit neighborhoods, where local business flourished, for social visits downtown, ‘the hub and nerve’ of the metropolis. Johns (2004, 5–6) recalls:

an overall cultural coherence … a nearly blind faith in progress, a strong sense of patriotism, a forward-looking attitude that lacked nostalgia, a prevailing dress code, a homogeneous mass market for consumer goods, and a process of assimilation so absorbing that writer Philip Roth remembers it as a period of “fierce Americanization.” The coherence of the ‘50s looks especially foreign from the perspective of today’s society, which affords nearly unlimited personal freedoms, places little trust in government, and relies heavily on the past for ideas, images and styles.

Apparently, manifesting Schopenhauer’s idealism, mid-twentieth-century urban development involved integrity of function and form. Yet, Johns also documents dark forces and downsides such that those impressions in the United States were ‘momentary,’ less than sufficient for an encompassing grace (cf. Harvey 2000, 170; Fainstein 2005, 11). At that time, Mumford ([1956] 1968, 108–09) noted ‘car-choked streets, the blank glassy buildings, the glare of competitive architectural advertisements, the studied monotony of high-rise slabs in urban renewal projects; in short, new buildings and new quarters that lack any esthetic identity and any human appeal except that of superficial sanitary decency and bare mechanical order.’ In The Australian Ugliness, architect Robin Boyd (1961) reported much the same as regards Antipodean cities reveling in a new trend of commercial ‘featurism.’

Against such backdrops, the most likely clues available to present-day searchers are the ‘best city’ league tables, covering retirement, tourism and general community amenity.3 Leading the community analysts, Sperling and Sander (2007) focus not on grace but on economy and jobs, cost of living, climate, education, health, crime, transportation, leisure, arts and culture, and quality of life. All these criteria are a good start and ones which, as will be seen, leave room for a crowd-sourced conclusion to the present inquiry.

With grace missing in action, why not simply substitute bliss? Such a quest has occupied ‘the grumpiest man on earth,’ veteran correspondent Eric Weiner (2008). His 413-page chase for happiness includes such disparate places as the Netherlands, Switzerland, Bhutan, Qatar, Iceland, Moldova, Thailand, Great Britain, India and America. Though devoid of academic reference, Weiner’s contribution makes a valid point for present purposes: barring a higher path to grace, even a little happiness would not go astray in an apparent ‘age of absurdity’ (Gorringe 2002, 9; Foley 2010; Osborne 2018). Helpfully, Montgomery (2013, 43) lists its keynotes. A happy city would be: healthy, maximizing joy and minimizing hardship, affording personal freedom, resilient, fair, sociable, communal and co-operative.

Lacking the omniscience of homo economicus, hope of revealing a real-world exemplar of The City of Grace now appears slim. The search thus turns to the more pragmatic theological texts which have actually considered the worldly concept of ‘place’ within urban function and form.

Outreach on the Street

As shown, grace and beauty are well theorized, and Beck (1999) has widened the account to western literature, music and art. Yet, apropos urbanism, the trail remains austere. A web search for ‘The City of Grace’ reveals the usual multi-million links, none exactly ideal. The US Library of Congress matches 625 of its 162 million holdings to relevant subject/title search descriptors, principally identifying the work of Johns (2004) and, ephemerally, Bernard (2004).

The latter author contributes to a tradition that commenced over 50 years ago with Harvey Cox’s ([1965] 2016) The Secular City. This seminal book, which attracted a large audience and lively debate (Callahan 1966), argued that secularization (as opposed to an ideologically rigid secularism) frees people from theocratic dogma and widens their ethical and spiritual positions. God is not confined to some special divine realm, nor to established institutions, and people of faith need not spurn a seemingly godless world. While endorsing such tolerance, Putnam and Campbell (2010, 493, 520) nonetheless note that not all expressions of religion advance the human spirit.

Considering that grace is offered gratuitously, Timothy Gorringe (2002, 2) provides its debtors with a ‘theological reading of the built environment.’ His Trinitarian approach4 would eliminate the pre-Christian distinction of the spiritual and secular, even though sacred and domestic spaces are regularly demarked in respect of the ‘great’ and ‘little’ traditions of architecture (#9). Contrasting with Old Testament experience, religious attention has focused on the retreat and ascendancy offered by holy buildings, leaving the rest of the city as a venue for evangelism or to fend for itself. Some reaction to this position arose in the optimistic secular city theology of the 1960s. It regarded the vernacular as a rightful domain of God, though its stance was challenged for its assumption that humanity had come of age, as well as for its muted critique of urban modernism.

To Gorringe (2002, 23–24), the subsequent liberation theology of the environment sought to call the world ‘home,’ but the systemic demographic and economic changes explained earlier called its homeliness into question. Cities can be regarded as places of creativity and heightened spirituality but also sin, violence and hubris—Jerusalem or Babylon, as it were. As part of this theological dialectic and reprised secularity, cities act as a genius loci to integrate purpose, meaning and ideas in a ‘creative spirituality’ and transcendent purpose without which, historically, they have died (#140, 161). ‘The built environment reflects not just ideologies but … spiritualities. Profound, creative, grace-filled spiritualities produce grace-filled environments; banal, impoverished, alienated spiritualities produce alienating environments’ (#24).5 Consequentially, urban centers are places where people can sin and isolate themselves to neglect God. As per liberation theology, cities could act redemptively to help the poor but, in reality, those unfortunates might be better off in rural poverty—minus urban pollution and crime.

Inge (2003) takes a religious lens to city planning’s interest in place-making. In establishing what makes a place holy, he concurs with Gorringe (2002, 1) that theological literature on place is ‘sparse,’ a surprising point for several reasons. Theorizing of place and space has evolved from Plato and Aristotle. Yet, after the late thirteenth century, space became the ascendant quantity, its infinity coming to represent the omnipresence of God. This conception complemented the discoveries of Galileo and, later, Isaac Newton, for whom places simply constituted a portion of absolute space. For its part, drawing on the philosophies of Descartes, Leibnitz and Kant, space subsequently deferred to time as the fundamental parameter in physical processes (Inge 2003, 8–9).

In the modern era, geographer Yi Fu Tuan (1977, 3) reasserted that space and place are, after childhood, the basic components of the lived world. Rather than validating this association, contemporary western society demonstrates a dehumanizing loss of place; precincts are penetrated and interrupted by far-distant influences, localities belong to investors not inhabitants, and space and time are fused by electronic media (Inge 2003, ix, x, 1–12; Gorringe 2011, 72). Implicit in concepts of instantaneity, the ‘global village’ and Thomas Friedman’s (2005) flat world6 is the death of geography, distance and space (Martin 1996; Cairncross 1997). Yet, the scriptures point otherwise, Genesis 2 assuming a three-way relationship among God, humanity and place. In the New Testament, places host meetings of God and the world. Thus, from both a relational standpoint and the biblical paradigm, there is a case to regard such places sacramentally, many distinguishing themselves since medieval times as sites of pilgrimage or as an eschatological sign of God’s future. Arguably, churches are significant places in elevating human experience. ‘Community and places each build up the identity of the other. This is an important insight in a world in which the effects of globalization continue to erode people’s rootedness and experience of place’ (Inge 2003, x, 1). In overlooking place, Inge (2003, 32) argues that theologians have ‘remained wedded to the norms of modernity which are being questioned in other disciplines.’ While placelessness is one thing, the counter applies that too effusive, conscious (neoliberal) place-making can be not simply inauthentic but culturally insensitive and profane (Gorringe 2011, 75).

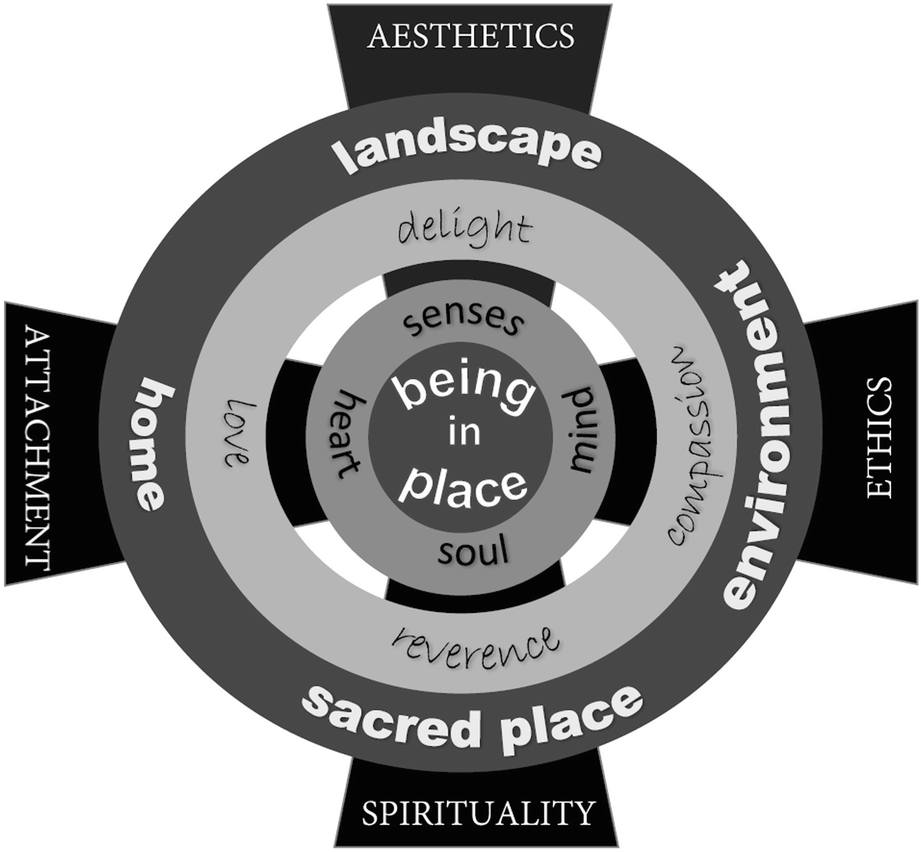

Intangible relationships with the environment. (Source: After Porteous 1996, 9)

Constructively, Holt (2007, 25) appraises the city by way of four criteria, each with up- and downsides. Regarding the latter, its size can make for superficial relationships compared with those embedded in a rural village. Density can cause urban residents to withdraw as a necessary facet of psychological survival (cf. Mackay 2018, 44, 48). Diversity can cause suspicion and mistrust, fostering retreats into protective subcultures which neoliberalism, given its individualizing outlook, could scarcely dispute. Commercialism can render most daily encounters instrumental and mercantile (Gay 1991, 75). Among these contingencies, ‘the ever-changing demographics of our cities say much about the way we naturally cluster with people of like culture, lifestyle and economic resources’ (Holt 2007, 28). Kaleidoscopic interchange can produce perpetual hybridization, ontological instability and little authenticity (Toffler 1970). Those looking for local ‘networks’ and ‘connection,’ or seeking ‘belonging’ and, ultimately, ‘community’ must navigate these realities.

To the urban-oriented theologian, modern suburbia demands its own analysis. Having framed it as ‘as much a state of mind as a place to live’ (cf. Healy 1994, xiv), Holt (2007, 34–39) quotes Marion Halligan’s (2004, 15) endorsement; namely, ‘one of the great achievements of the human spirit.’ With Gorringe (2002, 132–34), his view is more equivocal, variously settling upon the suburbs’ inception as an escape from the excesses of nineteenth-century industrialization; their friendly face to the mid-twentieth century created by front verandahs and porches which welcomed civic interaction; and the current incarnation of small lots supporting large (‘trophy’) dwellings fronted with multi-car garages and backed by manicured barbeque areas.

Hereby, collective privacy has ceded to a neoliberal, inward-looking reserve (cf. Ehrenhalt 1995, 254–55; Mackay 2018, 56–59). An overlay of public regulation and developer covenants acts to eliminate an experience of difference, creating placelessness by any other name. Though identity, ownership, space and family are all on offer, intrinsic feelings of homelessness and estrangement can imbue a place with a lack of soul. It is echoed in the 1990s tomes probing The Geography of Nowhere (Kunstler 1993; Eberle 1994). Kunstler (1993, 5), a journalist and novelist, maintains that ‘all places in America suffered terribly from the way we chose to arrange things in our postwar world. Cities, towns, and countryside were ravaged equally, as were the lesser orders of things within them—neighborhoods, buildings, streets, farms—and there is scant refuge from the disorders that ensued. The process of destruction … is so poorly understood that there are few words even to describe it.’ Eberle (1994, 19), a Mid-west academic, is concerned for people to find themselves in the postmodern world in which ‘incoherence, loss of center, and the relativity of virtually everything have been seen as the norm rather than as an aberration.’ Ironically, this passage was scripted before the virtual world had fully emerged: it speaks to Beth Milroy’s (1991) notion of postmodern ‘weightlessness,’ Douglas Porteous’ (1996) analyses of spatial anomie, Michael Foley’s (2010) age of absurdity, and the worries of Natalie Osborne (2018) about the contemporary Australian psyche. Mackay (2010, 35) nails the matter by way of three pointed questions about ‘my place,’ namely: ‘where do you come from?’; ‘where do you live?’ and ‘where do you feel most at home?’

a city which practices emancipatory koinonia7 in its total life process, where non-compulsive dialogue forms the basis of decision-making, where an interconnectedness of all beings is accepted, where maximal pluralism is promoted, where a moderate and just division of the total economic resources is the ideal, where shalom8 describes the contract between nature and man, and where aesthetics, ethics and religion are integrated in an existential understanding of what being a city implies. Man’s existence on earth should above all be a humble enterprise, with man being aware of his own trespasses. Likewise, humility is the ideal form of existence for a city [original italics].

Differentiating types of environmentalism

View/origin | Human-originated (anthropocentric) | Nature-originated (ecocentric) | Divinity-originated (theocentric) |

|---|---|---|---|

Narrow view | Techno-ecology | Ecofascism | Natural mythology |

Broad view | Deep ecology | Evolutionism | Ecotheology |

Approaching the Modeling

Though scientific method has been employed, searches in the real world and specialized literature have not pinpointed The City of Grace. Kjellberg’s (2000) theological account is, however, revealing: it places the present (secular) project in the anthropocentric fields of environmentalism and within St Augustine’s civitas terrena, rather than the heavenly civitas caelestis. Other elements of his thesis will prove useful as now, sufficiently informed by earlier chapters, we turn to deductive modeling of what will be a secular, centrist, ‘eco-tech’ city (Bogunovich 2002).

Model Foundations

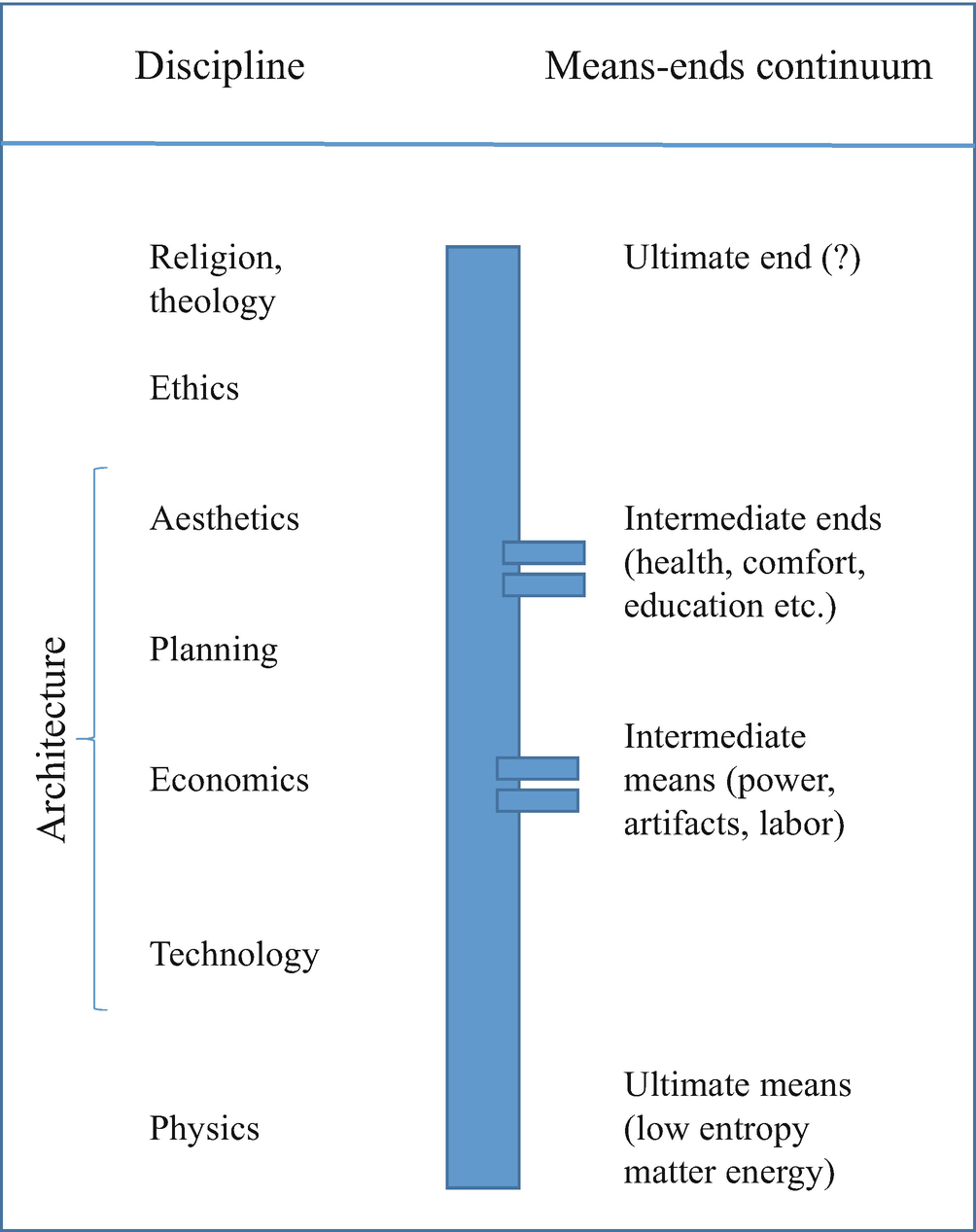

The spectrum of the disciplines. (Source: Adapted from Daly 1977, 19)

Embracing those of faith, Gorringe’s (2002, 161) theological and teleological positioning to urban development sits high on Daly’s means-ends spectrum. However, Gorringe explains that perfection will never be achieved on earth, another rationale for a secular approach. Such a stance aims to address an entire populace, improving upon a life of ‘quiet desperation’ for non-believers, and providing an aspirational platform for the faithful. The motive, seemingly ‘redemptive’ in Gorringe’s calculus, offers Paretian improvements and can meet Rawlsian welfare criteria (improving the lot of the worst-off in society).

Model Components

Like any other settlement, The City of Grace will reflect an interactive model in which the challenge is adequately to articulate the interdependencies. Its structure is as follows. The deliverables or aspirational outputs are produced by its internal system ‘mechanisms’ acting upon inputs, which consist of human, financial, environmental (natural) and manufactured (infrastructure, plant and equipment) capital. As in Fainstein’s (2010) acclaimed model, the processing applies to a settlement’s function assisted by its built form. Despite justifiable debate, such ordering first reflects the reality that structures are mostly functionally inspired and purpose-built: an assembly of them comes to constitute urban form.9 Second, as Banfield (1970, 8) remarks, ‘one has only to read Machiavelli’s history of Florence to see that living in a beautiful city is not in itself enough to bring out the best in one.’ To manifest grace, the assumption is made that the City’s function will be gracious and its form graceful, as determined by both public and private enterprise.

Supporting a vision and a mission, the necessary conditions involve three foundational precepts.

They underpin six strategies collectively sufficient to organize urban function and form to achieve a gracious and graceful product.

The strategies provide the entropic means by which The City will, as a system, avert chaos and deliver desired results.

The approach nominated, more formal and technical than those characterizing the urban modeling recounted earlier, can follow the grounded methods of strategic planning and project management.

Framework of the Model

Aspirational Outputs

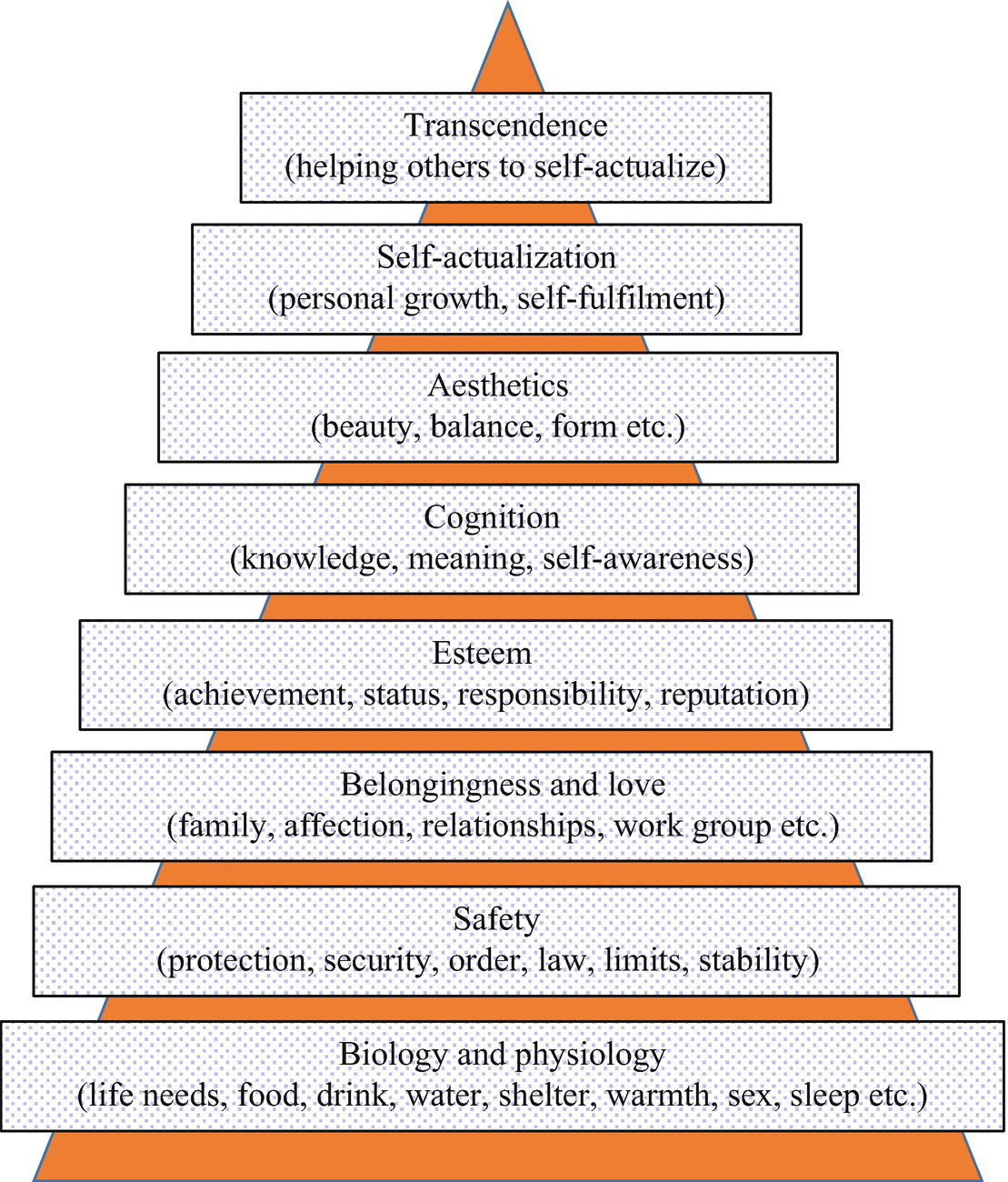

With theoretical and procedural foundations under control, we can nominate the primary outputs of The City of Grace. Reference is to the telos or meaning (Kjellberg 2000, 71), or, to refashion Daly’s (1977, 19) nomenclature, ‘ultimate ends.’ Just as an important one of Mackay’s (2010) 10 human desires is for ‘something to believe in,’ Hamilton (2003, 46) argues that ‘a sense of meaning and purpose is the single attitude most strongly associated with life satisfaction.’ At this level of discussion, an incursion into existential philosophy is a possible option. More economical for present purposes is to ask readers to indicate their highest level of engagement in Daly’s (1977) spectrum of the disciplines (Fig. 4.2). Though some will undoubtedly choose the upper realms, the present secular account, for its part, will not broach Daly’s ultimate ends. It puts aside theological intervention, transcendence or some imagined utopia for the lesser but realistic aspirations of self-actualization, well-being and an agreeable standard of living founded in personal motivation. These ends rest on three supporting constructs.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. (Source: Adapted from http://www.iloveulove.com/psychology/maslowhon.htm)

The second construct has various strands. Assuming that self-actualized people can maintain reasonable material standards, they have the basis for personal well-being and high quality of life. British philosopher, G.A. Cohen, wrote in the journal Ethics of 1989 that welfare, henceforth read synonymously with ‘well-being,’ can represent an agreeable state of consciousness (hedonic welfare) and/or a measure of the number of preferences a person is able to achieve (welfare as preference satisfaction). Influenced by Ghandian economics, Diwan (2000, 315–18) advances Cohen’s position. He defines quality of life as a state in which a person is at peace with: her/himself; nature or the environment; and society, in a narrow or broad sense (cf. Mackay 2018). He accepts that happiness or success depends on having a purpose and maintaining strong relationships with others, a condition termed ‘relational wealth.’ ‘Having’ a supply of private and social material goods and services primarily defines a standard of living, whereas quality of life involves ‘being’ and is associated with non-material values (Porteous 1996, 7). ‘For want of a better term, there is a certain order of spirituality in this idea. It also involves a life of voluntary simplicity’ (Diwan 2000, 316). At this point, we have gone beyond needs to satisfy wants or, alternatively, have overcome the need for wants. Popularly called ‘fulfillment’ rather than ‘greatness,’ such a post-material state might engage some of the divers constituents of grace.

States of amotivation, extrinsic and intrinsic motivation according to self-determination theory. (Source: After Ryan and Deci 2000b, 72)

External regulation, the first of four extrinsic types, involves compliance based on rewards and punishments emanating from other than the self (e.g. imposed ‘carrot and stick’ planning incentives). Top-down planning systems proposing edict before choice will likely elicit only extrinsic motivation.

Introjected regulation introduces some internal motivation and relies on self-control, ego-involvement and internal rewards and punishments (e.g. a self-administered regime of standards and values based around self-esteem) (Moller et al. 2006, 105).

Identified regulation involves a ‘somewhat internal’ perceived locus of causality. It evokes personal importance (i.e. things or issues significant to the individual) and conscious valuing, the latter behavior different from non-valuing amotivation. For a person in a planning context, greater awareness of civil society or civic issues might emerge by way of ‘returning something to the organizations which have supported me.’

Integrated regulation is the consummate point of extrinsic motivation, in which causality is seen as internal to the individual (i.e. a proactive rather than reactive position). Signature behaviors are those of congruence, awareness and self-synthesis as a person approaches self-determination. Place attachment and self-reliance to improve things would be anticipated, manifest in civic engagement.

Ultimately, intrinsic motivation is accompanied by intrinsic regulation, all fully internalized. Characteristic behaviors are those of interest, enjoyment and inherent satisfaction. Deci and Ryan suggest informally that children absorbed in play offer the most obvious demonstration of self-determination. Proactive citizens, willing carers and active community volunteers are their probable adult counterparts.

Theorists within this school of psychology acknowledge that people have basic but imperative demands such as those for food, shelter and security (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2000a, b). Assuming these physical requirements are met and also that people can raise their view beyond excessive materialism (Hamilton 2003, 104), conceptualization can concentrate on issues leading to personal or public mental health and, on a more elevated plane, well-being. Human behavior and experience convey meaning to people in their attempts to satisfy needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness. Thus, as an outcome dependent on these three independent variables, ‘well-being’ should constitute a key, higher level, pre-condition for a satisfactory quality of life. Extending Cohen’s (1989) view, Deci and Ryan (2000) relay two views of well-being—hedonic and eudemonic. The former is of well-being as happiness or a positive mood. Eudemonic well-being is more complex and involves the Aristotelian concept of a fully integrated person within society.

Self-determination theory asserts that success under external regulation results in hedonic, but not eudemonic, well-being. The hedonic path, more typical of top-down strategic planning, involves extrinsic aspirations such as wealth, but resultant happiness is often transitory and lacking fulfillment. Hedonism can effectively short-change intelligent people’s ontological security and quality of life. The pursuit and attainment of meaningful relationships, personal growth and community contributions align more closely with competence, autonomy and relatedness, which promote the fuller well-being represented in eudemonia. It is associated with vitality and self-actualization, producing personal growth, life purpose and self-acceptance, linked with the absence of anxiety, depression and somatic symptoms. The theory thus relates to conditions, such as those characterizing city planning and development, which optimally support human development. As individuals enhance their competence, autonomy and relatedness, they engage in self-determination which could aggregate to community level.

Having elaborated the three constructs underpinning the conceptualization of The City of Grace, we can now consider its operationalization. The components of the model include a vision and mission, allied with foundational precepts constituting necessary conditions for development. They are backed by strategies which badge the City and are sufficient to foster its existence.

Vision and Mission

As psychological as well as physical entities which concentrate human minds, most towns and cities have organically supported a vision, whether conscious and articulated or not (Batty and Longley 1994, 9). Mercantilism undergirded the typical settlement, capitalizing upon a river ford, trail junctions, a break-in bulk (entrepôt) port and so on. Statements of urban visions and missions can be easily accessed: Stanley et al. (2017, 19–43), for instance, consider those of Vancouver, Melbourne, London, Malmo (Sweden), Freiburg (Germany) and Portland (United States).

At its high level of systemic resolution, The City of Grace envisions individual and communal self-actualization, backed by intrinsic motivation, in seeking happiness and a standard of living supporting purposefulness, a worthwhile environment and quality of life. The vision presumes a concerted mission toward an agreed ethos offering hedonic welfare and enabling individual preference satisfaction. The City’s mission must engage committed people concerned about their life today and legacy tomorrow. They would have tested and found concepts of goodness and greatness wanting, and now, in ‘bonds of community,’ feel called, capable and vocationally responsible to current and future citizens for urban function and form (cf. Mackay 2018, 15, 26).11

This mission could engender debate. Libertarians will decry any collectivist involvement exceeding that for defense and maintenance of the (neoliberal) market. The rebuttal, invoking Schopenhauerian freedom, is that individuals might freely choose, bottom-up, to effectuate the mission, thus sidelining allegedly oppressive or imposed regulation (cf. Schoon 2001). Liberals might also dispute implied coercion or, otherwise, argue for various fancied and allocative ends. While Rossiter (2006) contributes a withering psychoanalysis of the liberal standpoint, the short response à la Grace is that undue liberalism, internal differentiation, identity politics and virtue signaling could produce ‘paralysis by analysis,’ defy consensus and fail to see the wood for the trees. Anarchists will meanwhile disparage any attempts at concerted and unitary action unless it advances their favored ends (or non-ends). However, there is little historical or philosophical relationship between such chaos and a state of grace (cf. Byrne 1997). Considering the environmental exigency outlined in Chap. 1, it is improbable that anarchic hedonism would appeal. As per Table 2.1, the City’s focus would need to be more mature and resolute as might attract replication in urban settlements elsewhere.

Necessary Processing Elements: Precepts

With the outputs, vision and mission established, the mechanics of the model need closer attention. Preliminary ideas permeate foregoing accounts of ‘good’ cities, a comprehensive example being that of Stanley et al. (2017, 16–19). As ‘outcome goals,’ these authors call for increasing economic productivity, a reduced environmental footprint, greater social inclusion and intergenerational equality, and reduced inequality. Their ‘process goals’ cover wide community engagement and governance which supports integrated land use and transport planning.12 Yet, on the fundamental but complex matters of how to sustain a successful economy, they are less than forthcoming.

In all such modeling, the devil resides not only in the detail but also in arranging elements (i.e. Daly’s (1977, 19) ‘means’) mutually and recursively to support each other toward the desired ends. Conscious of this requirement, the present formulation, as necessary conditions for gracious function and graceful form, prefers three foundational precepts, buttressed by several operating strategies sufficient to effectuate the mission and deliver the City’s vision.

First Precept: A Rational Context

Mention of anarchy inversely introduces the first precept necessary to the City’s operation, the embrace of rationality. Though usually unaddressed because of its problematic nature, the existence of rationality is seminal to, but simply assumed in, social science modeling. Recognition is lacking in both the urban literature and in current urbanism: Kjellberg (2000, 24) advises that ‘in the current so-called postmodern times there is strong skepticism toward rational, holistic thinking.’ More prospectively, Gorringe (2002, 147) affirms that ‘the supreme human goal is the exercise of our rationality.’ It must fulfill three requirements. The first is in orienting people to commit to action which they or others judge to be ‘rational.’ The second and third look at what those rational undertakings might entail both procedurally (what it takes to be judged ‘rational’) and substantively (the focus of behavior).

Apropos committing to action, Schmid (2007) writes that general (as opposed to political) philosophy has mostly been concerned with ego cogito, namely, individual, rather than nos cogitamus, collective, intention. Raimo Tuomela (1995, 2002a, b), Margaret Gilbert (1989), John Searle (1990) and Michael Bratman (1999) lead this more communal analysis. In graduating from individual free will to a person’s decision freely to concur with a group, one must relegate the idea of co-operation (well theorized) for that of co-ordination (Gardiner 2011, 88). The latter has escaped attention in microeconomic models of the single producer or consumer and remains less conceptualized because it ostensibly depends on known conventions.

The question, then, is how individuals might adopt a common strategy (involving, for example, a substantive application of rationality) (cf. Ehrenhalt 1995; Gleeson 2010). According to Gauthier’s (1975) interpretation, rational players who seek to maximize their utility but who do not know of any conventions will choose randomly between two strategies. If a condition within this decision-making is deemed ‘salient,’ the alternatives are to choose or ignore it, even though, for two players, the salient choice would provide a co-ordination equilibrium and a ‘payoff dominant’ or rational outcome. Yet, now, in an alternative sense, the existence of a non-salient solution makes that non-salient strategy also salient, though it is Pareto inferior. This development renders the initial salient course ‘weakly dominant.’ It will, however, prevail as the best ‘collective’ equilibrium if every person involved is (a) concerned with individual utility maximization, while (b) concurrently assuming that everyone else is likewise rational.

This conclusion not only nestles comfortably within the rational choice model in economics but, empirically, could explain results as diverse as recruitment of support around corporate plans in business (dissenters choosing to quit the company), as well as the onset of intentional communities as in kibbutz living, religious orders, eco-hamlets and retirement villages. Shared aims and mutual beliefs infuse such ‘team’ applications. They operate at a higher conceptual level than that of the individual decision-making underpinning orthodox economic models. They similarly depart from the individualization inherent in the neoliberal, ‘me’ society (Mackay 2018, 56). Conversely, they raise a specter of the ‘group mind.’ Historically, and at the extreme, it has totalitarian connotations and philosophical quandaries as to the possibility, beyond scriptural and Cartesian individual free will, of its actual existence. Various attempts have been made to accommodate this matter. Schmid’s (2007, 175) ‘strong’ conception is that collective intentionality does not have a single subject. Intentions have many subjects. ‘Thus the group mind is nothing we should be afraid of. It is merely a distorted individualistic image of a non-individualistic, holistic concept of the mind.’ It might also be less contentious if groups oriented themselves to objectives recognized to be effective, efficient and equitable as per welfare interests within microeconomics (Pindyck and Rubinfeld 2001). On this note, we can move on from mutual commitment to the second and third epistemological considerations surrounding rationality.

Starting from ground zero, Wikipedia relays the Kantian stance that a state of being rational depends on aligning one’s beliefs and actions with reasons to believe and act. These reasons need to be free-standing in regard to empirical contingencies; that is, to abstract from an individual’s particular circumstances and also withstand the critical scrutiny of others (d’Agostino 2011, 183). Yet, to the Dublin philosopher, Paul O’Grady (2002), a strong test must apply to the information behind a decision: rationality cannot be relativistic, as in simply running with the crowd. Action must first be goal-directed, that is, exhibiting agency. It is proactive rather than reactive (the latter state denoting, rather, that something has just ‘happened’ to someone). For O’Grady, the core elements of procedural rationality must be universal to avoid the travails of competing or relativist politics. This position has positive resonances within general systems theory.

He (#239–42) thus proposes four principles derived from two arguably universal components of rationality, namely, coherence and the use of evidence. The first principle requires avoidance of contradiction within a proposition. The second mandates inferential and evidential consistency. The third is non-avoidance of available evidence. It combines with the fourth, intellectual honesty, which would force a person to maximize the use of evidence pertaining to a case or decision. If a person thinks and behaves according to these rules, s/he could be said to be exhibiting rationality in decision-making or, otherwise, approaching a subject in a rational way. Upon reflection, it will be seen that this script is exactly that employed in law to determine the background to a case. It is, therefore, not only philosophically derived but also practical in everyday life.

Prominent in the social sciences are Max Weber’s (1864–1920) prescriptions regarding rational social action, outlined (rather briefly) in the first volume of his 1922 Economy and Society (Weber 1978, 24–26). He differentiates four forms, the first pair individually and the latter pair group-oriented. Instrumental rationality is conditioned by an agent’s expectations of a situation or behavior of others. It reflects appropriate adjustment to these elements. Value-rational action applies consciously to express an overriding commitment to a position or cause independent of any prospects of success. Affectual (especially emotional) rationality is determined by an actor’s specific affects and feeling, while traditional rationality accrues from ingrained habituation. It thus characterizes bureaucracies in which individual action follows customary, general rules, even though they might not reflect universal maxims. Rationality then becomes substantive when such institutions function effectively to meet publicly defined objectives (i.e. demonstrating allocative efficiency as in economics).

Despite this pairing, O’Grady’s approach appears procedurally purer than that of Weber (1978, 25), who regularly leans toward social substance (e.g. as in nominating values such as ‘duty, honor, the pursuit of beauty, a religious call, personal loyalty or the importance of some “cause” no matter in what it consists’). This last criterion echoes the inherent relativism of an allegedly ‘rational decision’ in city planning—‘one for which persuasive reasons can be given’ [original italics] (Taylor 1998, 70). Contrariwise, O’Grady’s case demands that (substantive) the focus of rationality be universal. Similarly, Alessandro Vercelli (1998, 261) disputes the alleged rationality of both ‘rational economic man’ and that discipline’s rational choice model. These formulations become inapplicable whenever time is irreversible and, alternatively, strategic learning is relevant but bears importantly on the state of entropy and onset of chaos. Incorporating relativism, they do not fulfill O’Grady’s conditions of procedural sufficiency.

The required philosophical universality might, therefore, be elusive, but could obtain when high-level instances of systemic resolution confront humanity. Such events include war, epidemics, a nuclear holocaust or collisions with space elements such as asteroids, each occasioning massive loss of life. Today’s emerging environmental crisis is relevant since ‘climate change is a truly global phenomenon’ (Gardiner 2011, 24). As outlined previously, the planet faces anthropogenic warming which could threaten its population (Dunlop 2013). While the risk is not necessarily one of complete human annihilation, death is certainly absolute for individuals. The environmental context involves recognition of systematic mistakes only ex post, hard uncertainty about direct cause-effect relations and the fixity of major decisions in the past (Vercelli 1998, 259). Time has seen the extinction of many sub-human species and, should anthropogenic activity generate system-wide and irreversible natural phase shifts, homo sapiens need not be immune (Goodrich 2014). Apocalyptically, we might not need to bother about heaven or hell in future urbanism: we would just peer out from a city to see environmental mayhem gliding into view. Gleeson (2014, 112–13) offers a scenario of how everything might actually occur. In sum, the second and third conditions of rationality consist of a strict procedural approach toward a universal substantive focus.

Second Precept: Sustainability

From this platform, a quite different and ‘alter-Weberian’ stance to rationality can be justified, namely, the application of individual and communal cognition to prospective species survival. This co-dependency unites singular and collective intention (Schmid 2007; Gleeson 2010). It can fulfill O’Grady’s strict criteria, and it differentiates humans from other forms of life which simply evolve, rather than being able to act rationally toward their own perpetuation. It also follows the kindred logic of the economist, Armen Alchian (1950), who maintained that neo-classical economic profit maximization was chimeric since its locus could not be established under uncertainty. The definitive position in real-world business is a realized result around zero dollars. This breakpoint where profits meet losses signals survival, if only for the time being, and survival is the first-order desideratum for most unimpaired individuals and organizations.

Logically, survival underpins sustainability, though this nexus escapes most of the literature, perhaps being taken as given. Neo-classical economists conventionally define sustainability in terms of the maintenance or increase of utility over generations. But, writes Daly (2005, 103), that interpretation is useless since utility is an experience, not a thing, and it cannot be bequeathed. Cross-sectionally and longitudinally, sustainability connotes the environment’s capacity to supply resources (natural capital) and to absorb wastes from the production and usage of goods and services (i.e. entropy change created by man-made capital or stocks of assets). Today, human activity is constrained not by any lack of industriousness, but by the supply of natural capital and, potentially, by the earth’s ability to eliminate wastes (especially GHGs and pollution).

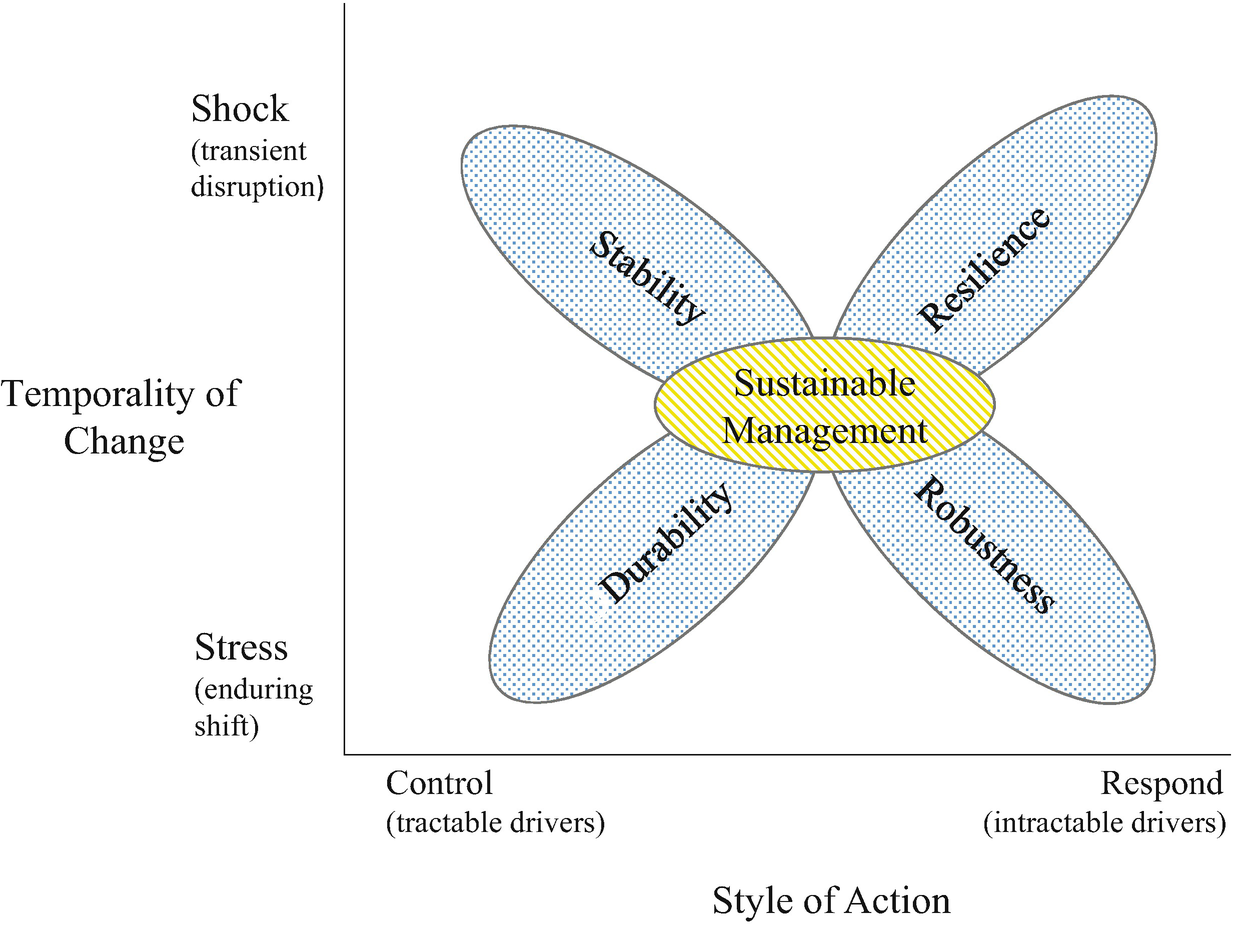

Dynamic properties of sustainability. (Source: After Leach et al. 2010, 62)

On balance, survival leading to sustainability can provide an acceptable substantive focus for procedural rationality. Viewed from the economic, social and environmental triple bottom line, it denotes the high level of systemic resolution implicit in Ehrlich and Holdren’s (1971) IPAT identity. Whereas twentieth-century modeling, usually around individual decision-making, was instrumentally facilitative and extended the frontiers of knowledge, circumstances in the natural environment now demand elevated thinking. Survival and sustainability play to either a virtuous or vicious circle. If the former prevailed, humanity would be tackling its impending problem with ‘Mother Nature.’ Either way, though, inhabitants of The City of Grace should act with survival in mind—and that could mean forsaking certain behaviors permeating neoliberal society (cf. Gleeson 2010; Mackay 2018, 23).

Third Precept: Low Entropy

To some readers, the discussion will have already taken a Calvinist turn. Sustainability can surely be taken for granted: now hosting hundreds of definitions, is it not a concept approaching its use-by date? Why not get into something more relevant and, most importantly, ‘vibrant’ in the neoliberal sense (Wadley 2008, 650)?

Rather than a series of sectoral booms and busts, low entropy indicates a system acting in an orderly manner, accepting its constraints (Mackay 2018, 11; Alexander and Gleeson 2019). It would eschew John Maynard Keynes’ ‘animal spirits’ or Alan Greenspan’s ‘irrational exuberance’ steadfastly to follow its objectives. Rational policy and decision-making should ensure that potentially disruptive positive feedbacks will be counteracted by negentropy to keep operations steady (i.e. accessing the tractable approach of Leach et al. (2010)). Many outsiders, weaned on media hype, political spin and sensationalism, would regard Leachean stability or durability as unfathomable, but businesses might welcome a largely predictable domestic milieu. The outlook would be neither boring nor sclerotic since certain kinds of growth and differentiation in both function and form would occur within system capacities. Substantial information about creating urban sustainability and continuity is available. With suitable strategies, it might be possible to overcome uncertainty, insecurity and placelessness by raising levels of co-ordination, trust and conviviality among the populace.

Sufficient Processing Elements: Strategies

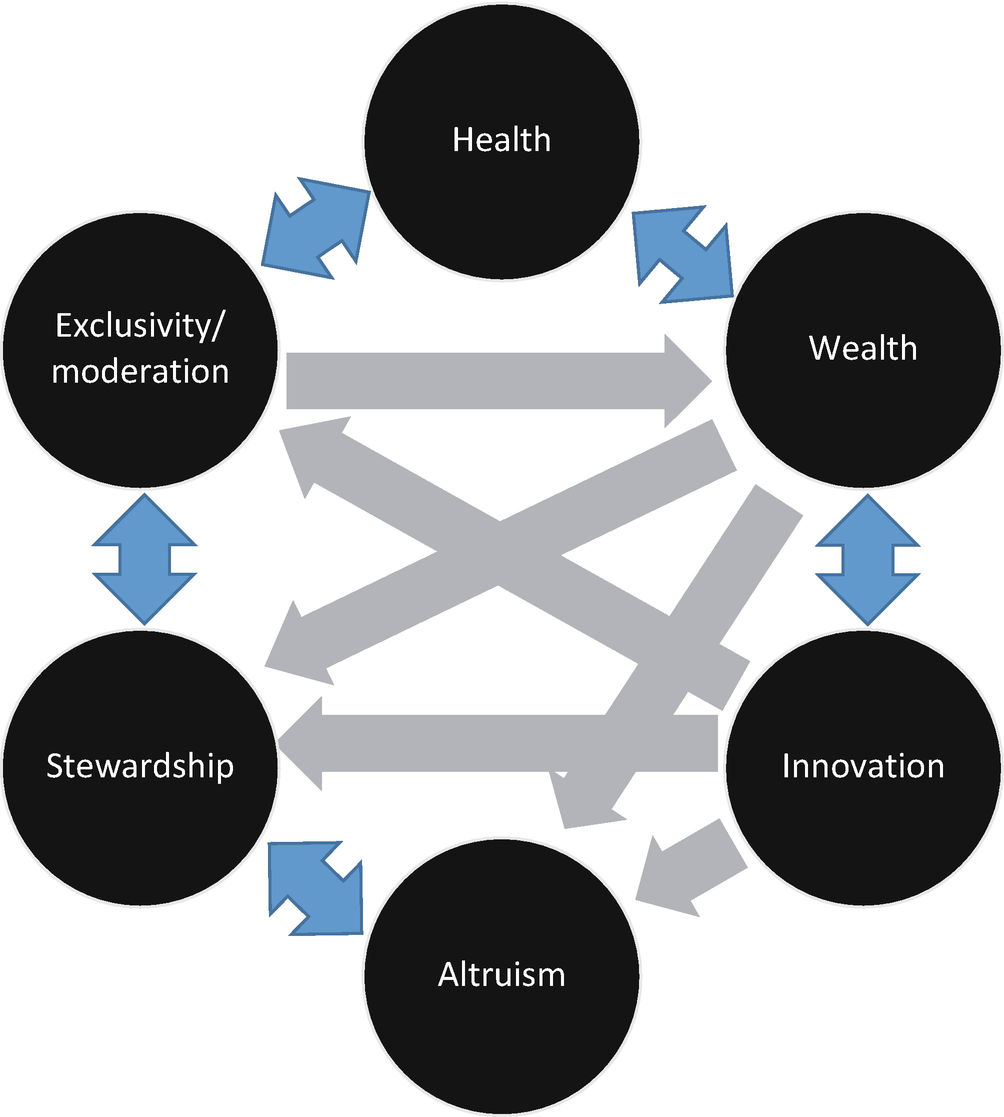

Key interactions among strategies, The City of Grace. (Source: Author)

First Strategy: Health

Health and wealth, the first two necessary strategies for the development of The City of Grace, present a chicken and egg problem. Both are indispensable but which is the primary one? Health underpins the Maslovian hierarchy and, since the days of Hippocrates, its importance has been singularly obvious. The bedrock of good health and sufficient well-being, both physical and mental (Friedmann 2002, 113), can be absent in poverty, signaling the need for at least enough wealth to provide relevant services. As the healthy city authors have remarked, good health is not simply about science and technique but also about popular access to quality provision, preferably assisted by a low entropy setting in which shock and mental stress are contained.

Second Strategy: Wealth

‘What is wealth?’ asks the British economist, James Ball (1992). He refers to Adam Smith ([1759] 1976) in The Wealth of Nations, only to find ‘wealth’ rarely mentioned. Though not consistently applied, the historical sense is of income per capita or overall productivity. Smith also draws a distinction between wealth and money (the latter, in the 1700s, gold and silver). He intertwines the concepts of wealth and ‘opulence’ (as a state of economic well-being) and, finally, distinguishes ‘productive’ from the ‘unproductive’ labor undertaken by menial servants, soldiers and entertainers.

Ball (1992, 5–6) responds that, today, wealth is understood as an asset stock yielding a flow known as income. Economic and general well-being should not be confused, indicating that there is more to life than the dollar. Accordingly, a fundamental problem remains that of determining whether an individual or society is ‘better off’ between two points in time—for example, would income per capita, disposable income, or net assets be the appropriate measure? Moreover, is the public or private sector the more efficacious in increasing wealth, income and well-being?

For balance, we leave this elevated discourse for the vernacular of Gordon Gekko’s ‘greed is good’ pronouncement in the 1987 film Wall Street. Though widely panned, it raises prospective leads in that ‘greed captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind.’ Later, Gekko advises that: ‘Sure, now what’s worth doing, is worth doing for money. If it’s a bad bargain, nobody gains, and if we do this deal, everybody gains.’ Less enthusiastically, Susan Fainstein (2010, 5) realizes that the capitalist system will not disappear overnight. Nor is she attracted by David Harvey’s prescription of perpetual conflict to overthrow it. As in her Just City and in Gay’s (1991, 98–99) reference to St Luke’s account of the shrewd steward, the requirement is to bargain the terms surrounding The City of Grace within the present global capitalist project. The only alternative is to model a rudderless utopia, akin to Michael Gunder’s (2014) reports of Auckland planning practitioners forced to pursue a discourse of fantasy.

So who can say a good word for poverty? Few in the real world except recluses would welcome it and theoretical modeling has emphasized its alleviation, not advancement or perpetuation. Hence, The City of Grace will not become an ascetic and introspective coma, hanging off some mountain cliff: rather, it must compromise with an environment of potentially chaotic capitalism. Gekko’s utterings can be dignified by advice contained in two venerable newspaper reports. First, channeling St Matthew’s parable of the talents, Brisbane’s former Anglican archbishop (and Governor General of Australia), Peter Hollingworth, advances that a sound Biblical approach is not antagonistic to the creation of wealth (Moodie 1993). It is a question of its uses and abuses. Wealth should help achieve a social vision which prioritizes benefits for the vulnerable and generates enough jobs for those who wish to work and live productive and creative lives. The four essential, collateral values are justice, sustainability, participation and efficiency.

Second, partially following Gay (1991, 96), the Melbourne philosopher, John Armstrong (2010), pursues this argument with insights about wealth ideally translating into worthiness:

What do people want a lot of money for? Many decent people aspire to earn large sums of money for reasons that are entirely respectable—they want long-term security for themselves and their families; they want personal freedom; they want to own fine things; they may, along the way, wish to contribute some of their wealth to good causes. Wealth is pursued as a means towards individual flourishing—that is, to being a finer, more complete, more worthy version of oneself. Wealth is not a necessary condition of being a good person, but wealth can be a condition for carrying out noble private projects … The ethic of wealth is not just to do with the value for money process by which it is accumulated; nor is it only to do with its the social utility. Ultimately, the ethic of wealth lies in self-regarding actions. Resources are a means of individual flourishing, of exercising the virtues of taste, wisdom and generosity on a large scale, with access to the finest products of human intelligence and imagination.

These views correspond with both commonsense, motivation theory and the rational choice model. In globalization’s unending migrations, people speak with their feet: they know that little can be achieved in poverty and so wealth is preferred whenever available. As Margaret Thatcher succinctly put it, ‘no-one would remember the Good Samaritan if he’d only had good intentions; he had money as well.13’ Wealth is thus the prerequisite not only to health but, further up Maslow’s hierarchy, also to altruism. It enables the adequate housing, remunerated work and social provision featured in John Friedmann’s (2002, 113) prescription of the Good City. Sustainable wealth could be the key to the beneficence inherent in grace. It confers the ability to assist those who might not have even asked for help. Altruism can meanwhile bestow gifts on the giver (Mackay 2018, 69).

Third Strategy: Innovation

Broadly, wealth first arises as the retention of the profit component of an income flow to organizations which engage in transactions. These exchanges occur in both the financial and the real economy.14 If not simply speculating, or arbitraging in markets, organizations normally create the comparative advantage required to produce a surplus either by becoming more efficient (i.e. increasing their productivity) or through innovation (as implied in Gekko’s advocacy of greed). Inevitably, the constitution of The City of Grace must embrace advances in goods and services as having unique potential to improve living standards and quality of life. Breakthroughs and cutting-edge technology offer people new capacities and benefits.

Gorringe (2002, 149) opines that creativity requires a balance between stability and anarchy since where there is perfect order (i.e. system equilibrium) there is death. He quotes Peter Hall’s (1998, 285–86) view that creative cities feature social relationships, values and views in transformation. Immigration (of talent) and cosmopolitanism are thought to contribute to ‘continual renewal of the creative bloodstream.’ Clearly, these orthodoxies will need balancing with the precept of low entropy.

Fourth Strategy: Altruism

Drawing on love, modern concepts of gracility suggest positive regard for welfare and equity, a generosity which might extend beyond, as well as within, city limits (cf. Fainstein 2010). As shown, wealth is improved when allied with (voluntary) worthiness, especially if the latter is applied effectively and efficiently. The City would rely on rules and laws, and individual and collective good works from its inhabitants. Recursively, they would attain opportunities for Maslovian self-actualization. The philosophies of Hume and Kant suggest the possibility of agreement on desirable qualities of life, such that inclusion, concord and civility could characterize social function.

Fifth Strategy: Stewardship

Since the Brundtland report, responsible stakeholders have recognized environmental preservation and enhancement as critical to human occupancy of the planet (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987). Various multilateral accords have instigated national attempts to limit negative economic and social externalities. If resource depletion and biophysical changes are as serious as experts have long maintained (International Energy Agency 2008; World Meteorological Organization 2008), there is no goodwill in denial, free-riding, chiseling, reneging, despoiling the commons or other forms of poor global citizenship (Doucet 2007). Though relegated by the 2008 GFC, ecologically sustainable development needs reassertion as more than rhetoric (Coyle 2011, 275). Current deliberation between mitigating, and adapting to, the effects of climate change might be academic. In Australia, Birrell and Healy (2008) insist that the government’s proposed 60 percent carbon cuts by 2050 will simply be annulled by the consumption of a wealthier population projected as 50 percent larger than in 2008. Such is the systemic applicability of the IPAT identity. With the relevant models predicting major environmental change well before 2100, quality of life will rest upon the sustainability generated by cities’ economic, political and social functions.

Despite localized green agendas (Racine 1993, 213), twenty-first-century urban grace should rely unequivocally on (macro) planetary stewardship.15 Today, its counterpoise is idleness, notwithstanding a need to remediate. In the west, satisfaction appears driven by strong materialism, which, with all its environmental overheads, could be difficult to change (Kjellberg 2000). Further, such is the power of globalization that investigation of serious alternatives has been thwarted by threats or fears of a significant loss of national socioeconomic welfare. The neoliberal agenda has fostered ideologies which, save for TINA admonitions, people might have disputed. Invoking the quality of gracility, the thrust in the City is whether any personal relief might be possible through different sociopolitical objectives.

These two basic facets, planetary accountability combined with individual utility, could be sufficient not only for the sustenance of urban life but the eventual accession of grace. Without environmental responsibility, we have no place worth living in. Without some utility, existence would be vapid (Kao 2007, 16). Accepting these essentials, our task is to investigate their achievement, first within the function, and then the form, of the City. Assisted by theory and practice, the analysis seeks the fulfillment created by divergence from both conventional urbanism and the less appetitive elements of global neoliberalism.

Sixth Strategy: Exclusivity/Moderation

The wellsprings of grace lie not in assumption but in endowment and incorporation. Its creation and maintenance in urbanism would be subject to exclusivity or ‘moderation,’ the latter derived from the Aristotelian ethical ideal of metron (Kjellberg 2000, 92). These concepts incorporate allied ideas of love, truth, order and freedom, which, along with foundational ones like trust and O’Grady’s (2002) evidential honesty, are far from universal. Life in the City would involve both intellect and effort as, for example, attempts to theorize atonement or the geometry of beauty have each demonstrated. Given the role of moral disinterest, if grace were not fully realized by its inhabitants, at least they would be able to retain humility or innocence. Initiatives to reduce public stress could attenuate domestic disruptions. Moderation and exclusivity, it should be emphasized, do not presuppose ‘exclusion’ since there need not be just one City of Grace in the world.

Leonie Sandercock (2003, 405) has written that ‘the completely profane world, the wholly desacralized cosmos, is a recent deviation in the history of the human spirit.’ The quality of exclusivity suggests that the City would, at least in some ways, be separated and redeemed (liberated) from totally encapsulating neoliberal mercantilism. Corroboratively, European urbanism prior to the Enlightenment strove to impart sanctification and salvation to its inhabitants, as illustrated by Johann Valentin Andreae’s 1619 Reipublicae Christianopolitanae Descripto (Hansot 1974, 79–92; Kohane and Hill 2001, 69; O’Meara 2005, 3646). As Racine (1993, 67) writes, ‘merchants founded cities to undertake commerce but the church reacted: was not the true purpose … to develop the Christian life?’ Some observers might therefore find more grace in medieval than in contemporary cities. Elsewhere in the world, the nexus of religion and the state remains unbroken and religiosity exists in the public domain. This practice reflects the NeoPlatonic view of one world in which the divine and secular intertwine (O’Meara 2005, 3645). If, today, The City of Grace were to be defined teleologically, it could lie outside the west.

If reserved, responsible, contrite and grateful, the City could appropriate some of Thomas Aquinas’ seven cardinal virtues16 and, likewise, avoid the seven deadly sins which date from the papacy of Gregory I (590–614 AD). Less relevant ones include: gula (gluttony), ira (wrath) and invidia (envy).17 More potent could be luxuria (extravagance, later lust), avaritia (greed), superbia (pride) and acedia (sloth). All are known to sap individual and civic morale. Adam Smith (1976, 184–85) dealt convincingly with luxuria. The downsides of Gekko’s avaritia and its alter ego, fear, castigated in the GFC of late 2008, need little elaboration. Superbia appears in political posturing and hubris and is arguably a facet of neoliberalism as it attempts to recolonize the world with its distinctive mores (Wadley 2008, 656). Acedia represents the listlessness, flaccidness and enfeeblement gripping the West as it grapples with events hubristically unexpected at ‘the end of history’ and the edge of chaos (Fukuyama 1993; Buchanan 2002).

Several orientations would be averted. From foregoing readings, the City will shun the ordinary or Pelagian mediocre. Given Banfield’s (1970) exposé of the unheavenly city, its form would not be physically ugly or uninviting. There will inevitably be insiders and outsiders, as with existing democracies and the presently bordered nation-state (Flint 2003, 54; Ross 2004, 7, 104–05; Blackwell 2013, 284–87). Hopefully, with its precepts and strategies, the settlement can reflect a unified character, undertake good works and offer senses of tranquility, order, harmony and reason so as to demonstrate purpose. It might afford more certainty than the neoliberal world beyond. Grace revolves around quality, rather than quantity, and chooses measure, efficiency and elegance over extravagance. Acknowledging the ascetic but avoiding its excesses, a workable perspective could be informed by the steady-state economics of Herman Daly (1977), the theses of E.F. Schumacher (1973) and other studies which controversially dispute neoliberalism to claim that nature, people or the world actually matter (e.g. Short 1989; Poirrott 2005; Nelson 2006). In all these ways, moderation would contribute to the critical principle of managing urban entropy, an overarching condition of sufficiency in the model proposed.

Leads in Modeling

In foregoing chapters, construction of The City of Grace has been explicitly situated in a non-utopian, secular context. Its empirical backdrop is a world of unrelenting demographic growth, globalizing, expansive neoliberalism, a destabilizing natural environment and fast-paced urbanization. Given the dynamism and uncertainties, employment of general systems and chaos theories as central explanatory tools is essential. The literary lineage of the proposed model includes a wide array of themed and general urbanist texts. The focal component, grace, has been explained in its theological, ascetic, aesthetic and material expressions.

This chapter, having searched unsuccessfully for a real-world City of Grace, reviewed more specialized literature, and then set out the model’s foundations. First came the desired outputs. Maslow advanced that basic needs must be addressed before people can turn to higher-order ones and eventually undertake a move to self-actualization. Cohen defined two conditions of human welfare or well-being and Diwan added prerequisites of inner contentment and the constituents of a meaningful quality of life. Ryan and Deci emphasize autonomy, competence and relatedness as routes to the intrinsic motivation which underpins psychological fulfillment. Autonomy could be a particularly important quality since City organization would need to be seen as legitimate and assented to by the populace. In this way, citizens’ engagement would be volitional, not imposed.

Aggregate process model of The City of Grace

Inputs | + Intermediaries | Processing mechanism | Outputs (objectives) |

|---|---|---|---|

Capital: • human • financial • environmental • manufactured | Concepts of Grace: • as per Table 3.1 Precepts: • rationality • sustainability • entropy Strategies: • health • wealth • innovation • altruism • stewardship • exclusivity/moderation | Urban: • function • form | States of: • actualization • motivation • welfare |