Reflection upon the human condition should not deal in optimism or Schopenhauerian pessimism but, rather, and always, in realism and reason. Though, obviously, many minor circumstances could affect The City of Grace, the big picture counts more. Significant roadblocks thus comprise charges of utopianism, popular acceptance, and the possible denouement of capitalism. By contrast, rationality in future affairs could create a pathway to progress. We move to expose and deal with these themes.

Utopianism and Acceptance

While utopianism usually posits an ideal, upside condition, the present account is more constrained to avoid significant downsides. And, whereas the relevant utopianism of Mumford’s (1922) historically respectable type has been acknowledged, it should be explicitly distinguished from that of the lazy, hazy 1960s—with epithets such as ‘imagine all the people living for today’ and ‘all you need is love’ and so forth. Such sentimentality can segué into listlessness (acedia), indecision (such that if you believe in everything, you believe in nothing) or learned helplessness. This soggy embrace could suffocate any sustained modeling and should find no favor with realists. A levelheaded compromise invokes John Friedmann’s (2002, 103–04) critical and constructive vision: ‘utopian thinking [is] the capacity to imagine a future…radically different from what we know to be the prevailing order of things.’ The City of Grace is only somewhat different and, to that extent, achievable.

Robertson (1989, 20) writes of valuing people and the earth, a plaintive call, were it not echoed by authors like Schumacher (1973), Daly and Townsend (1993), Nelson (2006) and Coyle (2011). So, is The City of Grace dependent, as in the past, on illustrative narratives, or could it be a metaphor for energization and a different epistemology of prospective urbanism? Its secular and industrious intent has been painted as exclusive, but positively so. Some will deem it not worthwhile; others will see a hard life in its resolute communitarianism. For hedonists, libertarians, anti-regulationists, perpetual adolescents and anarchists, a large and lively realm beckons outside. It is both germane and non-utopian to posit this worldly trajectory, if only in the default setting that ‘if you don’t like “grace”, sample the graceless and potentially chaotic alternatives.’ In this regard, what could be defined as popular, business-as-usual capitalism, incorporating global neoliberalism? In fairness, picturing it could offer observers a basis of choice (cf. Freestone 1993; Schoon 2001).

The Future of Capitalism

Alexander and Gleeson (2019, 6) submit that ‘capitalism has run aground on the reefs of contradiction and overreach.’ To expand their littoral analogy by enlisting chaos theory, the neoliberal compact appears as a pressured system, represented by a surfer attempting the Quasimodo.2 The approaching wave of unchecked population growth forces the board (capitalism) along. The move involves the rider (humanity) bending forward with hands upraised and head down, passage uncertain, a wipeout or collision ever possible. Indeed, the last 30 years have seen not simply a retreat of socialism but repeated, synchronized, worldwide contortions of capitalism3 in the 1987 market crash, the 1997 Asian meltdown, the 2001 dotcom bubble, the 2008 GFC and later quantitative easing. Australian businessman, Tim Hughes (2008), chides that the weakest companies must be saved because they are deemed too big to fail4: ‘the old Politburo warhorses must be laughing in their graves to see capitalism get its comeuppance.’ Even so, people lost their shirts, jobs, partners, dogs and pick-up trucks in these crises. Others lost their lives in the global war on terror, assorted epidemics, and human or natural disasters. In a modern take on the life of desperation, Cooper (2004, 77) resignedly observes that ‘we may not be interested in chaos but chaos is interested in us.’

Apart from the transaction of physical (solar) energy (Daly 1977, 19), global capitalism essentially represents a singular, closed system, determined by irreversible, foregoing conditions (aka ‘the signature of chaos’) and unstable, aperiodic behavior (Goudzwaard 1979, 152–53). Though Gore (2013, 35–35) muses about a ‘sustainable capitalism,’ Alexander and Gleeson (2019, 14) identify ‘a convulsive instability at the heart of human prospect [sic] that contradicts the predictive confidence of popular urban commentary.’ Alternatively, The City of Grace could offer an outpost of relative stability, its precepts and strategies capable of checking entropy. To probe this contrast, we must consider two possible crises, environmental and internal, which capitalism could create through its own devices.

Capitalism’s Physical Environment

We are more powerful than ever before, but have very little idea what to do with all the power. Worse still, humans seem to be more irresponsible than ever. Self-made gods with only the laws of physics to keep us company, we are accountable to no one. We are consequently wreaking havoc on our fellow animals and on the surrounding ecosystem, seeking little more than our own comfort and amusement, yet never finding satisfaction.

In the journal, Futures (2015), Australian authors, Melanie Randle and Richard Eckersley, asked respondents, ‘in your opinion, how likely is it that our existing way of life will end in the next 100 years?’ and, further, ‘how likely is it that humans will be wiped out in the next 100 years?’ In Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States, 54 percent believed that there was a 50 percent or greater probability of experiencing the end of ‘our existing way of life.’ An average 24 percent foresaw the same chance of the elimination of humanity within a century. First, ‘our way of life’ could refer to the viability of the western order. Relevant literature includes warnings by former US presidential nominee, Patrick Buchanan (2002) about immigration and ennui transforming America and Europe, recently rehearsed by Murray (2017), and more broadly pursued in Goodhart’s (2017), Frank’s (2018) and Hitchens’ (2018) polemics about those continents’ current politics. They bow to the geographically wider ‘provocation’ of Singaporean commentator, Kishore Mahbubani (2018). He criticizes ‘suicidal’ war engagements, the operational blindness of élites, and running on ‘autopilot’ underpinned by naiveté and ideology. ‘It is inevitable that the world will face a troubled future if the West can’t shake its interventionist impulses, refuses to recognize its new position, or decides to become isolationist and protectionist’ (#91). A troubled world is not helpful to constructs such as a City of Grace.

Randle and Eckersley’s second inquiry about ‘the elimination of humanity’ ups the ante. Today, even an institution as traditional6 as the Catholic Church has misgivings. The 2015 papal encyclical, Laudato Si (see bibliography entry ‘Francis’), written to all humanity and not just adherents, rightly asks, ‘what kind of world do we want to leave to those who come after us, to children who are now growing up?’(#160). It acknowledges a crisis around climate, water, loss of biodiversity, declining quality of life, societal breakdown and global inequality. Of human settlement, it observes (#44):

Nowadays, for example, we are conscious of the disproportionate and unruly growth of many cities, which have become unhealthy to live in, not only because of pollution caused by toxic emissions but also as a result of urban chaos, poor transportation, and visual pollution and noise. Many cities are huge, inefficient structures, excessively wasteful of energy and water. Neighbourhoods, even those recently built, are congested, chaotic and lacking in sufficient green space. We were not meant to be inundated by cement, asphalt, glass and metal, and deprived of physical contact with nature.

Pope Francis argues that today’s global interdependence requires universal plans and reforms (cf. Rifkin’s (n.d.), ‘biosphere consciousness’ as opposed to ‘geopolitics’). Yet, who is inclined to listen? Although, as posted by Evans (2019), the chief executive of the large global miner, BHP, has latterly warned that dependence on fossil fuels poses an ‘existential risk’ to the planet, authors Mazutis and Eckhardt (2017) generally chastise business for dismissing climate change on account of several inbuilt cognitive biases, those of perception, optimism, (ir)relevance and volition. Their experience with industry appears to corroborate Hamilton’s (2010, xii) earlier lament that ‘after a decade of little real action, even with a very optimistic assessment of the likelihood of the world taking the necessary action and in the absence of so-called unknown unknowns, catastrophic climate change is now virtually certain.’

In these circumstances, the United Nations (2013) compiled a register of six hazards potentially impacting the world’s 633 cities with populations over 750,000 in 2011. The climate-related instances covered: floods, affecting 224 settlements with 663 million inhabitants; drought, 134 cities, 278 million; cyclones, 68 cities, 229 million; and landslides, 6 cities, 12 million people. The figures quoted are only those for settlements in the eighth to tenth most exposed deciles: many more could be less severely affected. Moreover, some areas face multiple natural hazards. The report (#24) identifies 205 cities of over a million population subject to one type of hazard, sixty-one facing two, and seven exposed to three. Africa and Europe are the continents least affected. As to future population gains, and consequent outcomes from climate change, these data generated from historical sources can only be regarded as baseline or speculative. Moriarty and Honnery (2015) take the results beyond immediate damage and destruction into important second-order impacts such as those affecting health.

Former energy industry executive, Ian Dunlop (2013, 139, 142), escalates the case. He maintains that two degrees of warming will, over time, result in six to seven meters of sea-level rise, while four degrees could produce seventy meters following significant polar and tundra melting. Thus:

Political and business leaders glibly talk about adapting to a 4° C world with little idea of its implications. It is a world of one billion people or less [sic], not seven billion, caused by a combination of heat stress, escalating extreme weather disasters, sea level rise, food and water scarcity, with consequent social disorder and conflict.

climate change is every bit as alarming as any of the threats facing humanity, and probably more alarming than most, because—without drastic change—its impacts appear certain. So …its effects matter fundamentally to everyone: what is at issue is not comfort, or lifestyle, but survival. (Kirby 2008, 23) [italics added]

Alexander and Gleeson (2019, 49–51) warn of ‘the moral hazard of possible technological solutions,’—that is, in following optimists like Matt Ridley and the late Herman Kahn to place faith in the (T) of the IPAT identity (Ehrlich and Holdren 1971). The (2019) authors’ argument should not be read as being anti-technology per se, nor disputing the utility of innovation as favored in The City of Grace. Rather, it applies to hope of ‘technological solutions’ at large saving humanity from a situation of its own making. Both economic and physical lenses can be applied.

Economically, in determining total factor productivity (TFP) in national accounting, the influence of technology is usually calculated as any component of gross product existing after acknowledging the contributions of labor and capital (Stiglitz and Walsh 2002, 583–85). To achieve an effect in mediating environmental impact (I), this measure of technological or quality change would have to outweigh the multiplicative influences of (P), population stocks and growth, and (A), affluence sometimes also interpreted as ‘attitude.’ Assume that, worldwide, the product of (P) ∗ (A) amounted to 3 percent per annum: technological advance would then have to better that rate to achieve any TFP. Yet the focus here is upon aggregate technological progress, not all of which would be oriented to, or have any ameliorating effects upon, the environment. A total of 3 percent is also a prodigious annual rate of growth in TFP. Population and affluence are likely to be far more powerful than technology in influencing the human condition. For positive and realistic consequences, control of population is the pivotal variable.

+14 GT CO2e from increased per capita consumption (A, affluence in the IPAT identity)

+4.2 GT CO2e from population growth (P, as above)

(−)8.4 GT CO2e from increases in efficiency and technological improvements (T, as above)

(−)1.5 GT CO2e from changes to the composition of consumption (A)

+0.6 GT CO2e from changes to trade structure (T, technology, possibly a result of globalization)

Overall increases in carbon dioxide emanating from consumption thus exceed efficiency gains by 5.6 GT CO2e, or an additional 66.66 percent above the 8.4 GT CO2e technology offset (5.6/8.4 × 100). Including emissions consequent upon population growth, the gap rises to 9.76 GT CO2e, or 116 percent of the total reduction. From this evidence, Alexander and Gleeson’s (2019) caution about ‘moral hazard’ again looks justified.

To conclude this sorry section, global leaders meeting in Davos, Switzerland, recently rated ‘failure of climate change adaptation and mitigation’ as the second of ten global risks in terms of both likelihood and impact on humanity (World Economic 2019). All these sentiments render somewhat anodyne and complacent the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development definition of sustainability—not doing anything now to impact the welfare of future generations. ‘Physician, heal thyself’: the global population 30 years ago was 5.02 billion!

Capitalism’s Internal Dynamics

The second worry,8 also bearing on population issues, concerns the systemic viability of so-called late capitalism. Karl Marx’s critique in Das Kapital has attracted many authors, a frontrunner being David Harvey (1982, 2014 inter alia). His appreciation of spatial and temporal unevenness, along with class struggles, has encouraged diverse inputs including the 1996 works of Gibson-Graham, and Webber and Rigby. Other than fundamentally ideological objections also exist, such as Albert’s (2003) advocacy of a participatory economy, Davis and Monk’s (2007) exposé of neoliberalism’s ‘evil paradises…in former mob hideouts,’ and Piketty’s (2014) celebrated analysis of capitalism’s structural inequalities. How might things play out?

The concern here is not with consumption and overproduction, as trouble Gleeson (2014) and Alexander and Gleeson (2019, 8–10). Instead it relates to the factor input mix. Dicken (2015, 322–23) records that the world’s labor supply quadrupled between 1980 and 2005. From 1995 to 2025, he cites a prediction that only 1 percent of its growth will occur in developed countries, leaving the International Labor Organization to fret over a supply-side crisis ‘of massive proportions’ as 46 million people per year enter global employment markets. Economic activity, the basis for human survival, involves a complex system of land, labor, capital and management. Unsurprisingly, capitalism is about capital and, since the Industrial Revolution, technological progress has orchestrated its substitution for labor in the factor mix. Finn Bowring (2002) of the University of Cardiff has gone as far as to claim that the objective of the most efficient organizations is the elimination of work (i.e. by humans). Six trends buffeting labor include: the accessing of internal and external scale economies in production; ongoing product and service development incorporating simplification, modularity, weight loss, miniaturization and multi-functionality; digitization, robotization and augmented/artificial intelligence; outsourcing and offshoring; casualization and contracting; and shadow work in which corporations inveigle consumers to undertake free work for them.

Heeding early lessons about contemporary risk relayed by Hacker (2006, 60–85), labor issues in parallel with its overall demography would be closely watched in The City of Grace. It could be noted that proactive management of labor force dynamics is effectively a radical idea given the general slackness applying in rich nations where capital calls the shots. Currently, various pundits, including some of the world’s largest business service firms, are debating whether the aggregate demand for labor in advanced countries will rise or actually fall, especially in light of potentially revolutionary ‘system-embracing’ technological changes such as quantum computing (cf. Dicken 2015, 76). The implications extend beyond a single city, nation or factor share. After five Kondratieff waves, humanity could be reaching a new technological asymptote, making it difficult to imagine many meaningful, labor-absorbing, new products and services and thus tilting toward Hamilton’s (2003, 80) and Russell’s (2011, 221–22) anticipation of a post-consumptive environment. As to Gore’s (2013, 5) suggestion that ‘the world has now emerged as a single economic entity that is moving quickly towards integration’ [original italics], European sociologist, Zygmunt Bauman (2007, 28, 30) adds the alarming observation that:

the volume of humans made redundant by capitalism’s global triumph grows unstoppably and comes close now to exceeding the managerial capacity of the planet; there is a plausible prospect of capitalist modernity (or modern capitalism) choking on its own waste products which it can neither reassimilate nor annihilate….As for the ‘redundant humans’ who are currently being turned out in the lands that have only recently jumped under (or fallen under) the juggernaut of modernity, such outlets [i.e. new spatial frontiers] were never available; the need for them did not arise in the so-called ‘premodern’ societies, innocent of the problem of waste, human or inhuman alike. [original italics]

modeling the function and form of The City of Grace takes a precautionary and defensive position (cf. Bailey 2005, 310);

despite its elevated systemic level, the model is not utopian but, instead, anti-dystopian; and

it might act as a constructive alternative to neoliberal development, even though existence of the latter is assumed for the sake of realism.

The City puts forward an intentional future involving a known agenda and potential certainty, as against the lack of teleological direction, or maybe, pernicious misdirection, of prevailing market forces. There is no guarantee, however, that a single City, or even a cohort of Cities of Grace, could overturn current trends or that there would otherwise be a positive ‘transformative crisis,’ to quote Gleeson (2014, 112). Consequentially, it is relevant to consider any alleviation potentially accompanying the application of rationality in urban development.

The Pathway to Rational Progress

Ensconced in philosophy and psychology, rationality and its alternatives lie among the supreme ends in Daly’s (1977, 19) scaling of the disciplines. They also propose the highest level of systemic resolution in world affairs: as follows, if the word ‘rational’ is to mean anything, its application must extend beyond the individual such that collective conduct is either rational or not. That important dichotomy can be understood by considering procedural and substantive senses of rationality as they influence management of urban and other environments.

In his book on Relativism, O’Grady (2002) argues that a procedurally rational action should be judged around a minimal list of non-relativist criteria and also by its treatment—how one acquires it, integrates it with other beliefs and by what one does with it. Core elements of rationality must be universal, whereas localized ones need not be. ‘Universal’ could signify maxims, which are consensually affirmable, free-standing in relation to empirical contingencies and independent of an individual’s particular circumstances.

As to substantive rationality, it is certain that, under current auspices, the natural environment upon which we depend will, in the absence of remarkable technological change (e.g. overcoming the second law of thermodynamics), feature irreversibility and irreplaceability. The context is one of depletion of non-renewable resources, extinctions of species and loss of biodiversity. Systemically, it is both deterministic (in that impacts can cumulate over time) and also stochastic (meaning that maverick variables can produce random occurrences of differing likelihood and consequence). With positive feedback, there can be tipping points or phase shifts, which can accelerate and cause structural or aggregate changes. Nonlinear, dynamic systems host vast numbers of independent variables interacting in multitudinous ways and producing unintended consequences (Novak 1982, 89), yet complex systems are able to balance order at the ‘edge of chaos.’ This margin of transition hints at a phase shift between stability and a high-entropic slide into total dissolution, as has happened periodically to human societies (Sardar and Abrams 2013, 15, 82).

With this backdrop, rational action and survival appear linked because, in their absence, there is no human context to superimpose upon the natural one. This position has the advantage, rare in philosophy, of absolutism, since it is about life and death. Hence, in a poorly recognized way, our oft-cited, much-touted ‘sustainability’ must somehow depend upon human rationality. Individually, but, more significantly, collectively and at the highest level of systemic resolution, we should redefine sustainability as the application of rational action toward anthropogenic survival.

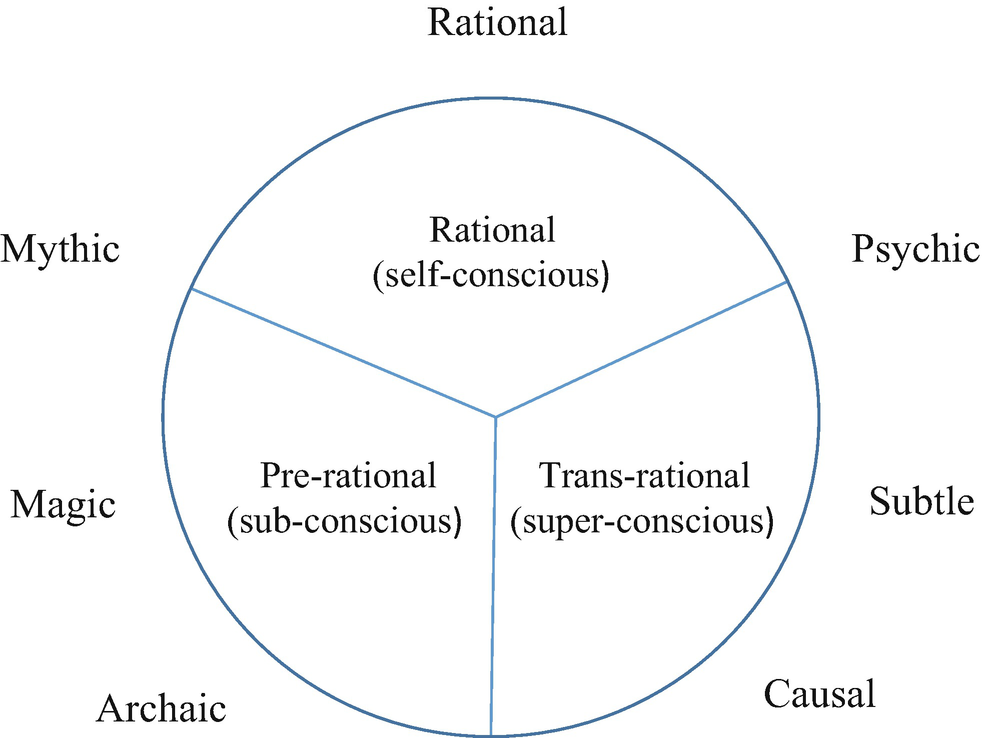

Reflecting a symbolic world view, the pre-rational, sub-conscious realm has ‘archaic,’ ‘magic’ and ‘mythic’ levels relating respectively to: animism, pantheism and orgiastic modes; rituals and, enchantments; and the energies of nature, the essence of humankind and semi-divinity. It corresponds with Maslow’s physiological needs.

The trans-rational, super-conscious realm in its ‘causal,’ ‘subtle’ and ‘psychic’ levels lies atop Daly’s (1977, 19) spectrum of disciplines as it taps clairvoyance and intuition, the divine and enlightenment, and eschatology and dreams. It reflects Maslow’s belongingness and self-actualization/transcendence needs.

Self-conscious rationality, correlated with Maslow’s self-esteem needs, at once involves a level of reason, analysis and measure in a framework of morals and ethics. It helps create the institutions of the modern world and pursuit of science and technology. However, it is also associated with dysfunctional compulsions and obsession with self-conceived truths and perfection of standards.

Realms and levels of consciousness. (Source: After Wilber 2001, 225)

While Hamilton (1994, 122) endorses elements of the pre-Enlightenment organic worldview (as in the contemporary rise of environmentalism and validating of indigenous cultures), Conway (1992, 227–36) charges that modernism has locked advanced societies too strongly into self-conscious rationality. It stresses instrumentality at the expense of other realms and worldviews (which might question pure materialism and relate somewhat more to grace). Three refrains apply. First, the objectification and metrication of contemporary capitalism illustrate the downsides in pursuing self-conscious rationality too strongly. As Martin Buber ([1937] 1970, 109–10) remarked, ‘the capricious man does not believe and encounter…he only knows the feverish world out there and his feverish desire to use it…he cannot perceive anything but unbelief and caprice, positing ends and devising means. His world is devoid of sacrifice and grace, encounter and presence….’ Second, this self-conscious rationality can explain neoliberalism’s compulsion toward growth. Third, for these reasons, what Conway (1992, 228) calls ‘the rational ego’ will require some calibration and management in its involvement with The City of Grace, lest qualities such as charm, beauty, beneficence and selflessness retreat (Table 3.1).

In modeling urban grace, two questions ensue. If the City can, in fact, survive by achieving procedural and substantive rationality, where does that leave the rest of the world, given its lack of unified leadership and potentially chaotic neoliberalism? Further, have we reached such a stage of (dis)illusion and hubris that the desires to be rational and sustainable should be dismissed as dissociative and ‘utopian’?

Summation

The roadblocks and pathways to The City of Grace relate to its possible utopianism, uncertain acceptance, the state of its surrounding neoliberal environment, and the potential for rational decision-making.

Regarding utopianism, it should be remembered that human settlement inevitably follows models. Early types of organization evolving into feudalism were adequately appraised by Karl Marx. The Industrial Revolution begat thinkers like Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill who fostered classical liberalism, transformed from the 1940s in the work of F. A. Hayek, Anthony Fisher, Milton Friedman and others as the neoliberalism of today. In that it represents the world as we know it, neoliberalism is not usually (and probably for good reason) seen as utopian, but it remains a model with its own system dynamics. Despite becoming a ‘solid fact’ in Mumford’s (1922, 14) terminology and notwithstanding the claims of Frances Fukuyama, it might not after all represent ‘the end of history.’ Should it and its libertarian backers fail, neoliberalism could, in the hindsight of those who survive it, appear more conceptually utopian than the moderate City of Grace.

Grace might have benefits beyond goodness and greatness but, as with everything in life, comes at a cost. Its prospectus will not attract everyone. For the present, there are plenty of alternatives for the ‘ecologically illiterate’ and dissenters to maintain their ‘apparently innocent’ interest in ‘beliefs and value systems that would seem to place apparently irrational and dogmatic restrictions upon the programme of practical improvement’ (Gay 1991, 79; McFague 2008, 56). The City has been situated in a capitalist environment which, contrariwise, will influence its success. Therefore, as roadblocks, two macro-level failure modes of capitalism have been examined. As neoliberalism evolves, they are not assured but, recalling the principles of scenario-building, nor are they fanciful (Hirschhorn 1980, 181). They are plausible and might contain chaotic elements of surprise, which could produce dramatic change if either of the cited sequences occurs.

Rationality pervades the construction of The City of Grace but, in the real world, is a contested and far from a free good. From the author’s theorizing of its individual and collective expression, it can be defined as the application of reason to human survival. Like Gleeson’s (2010) urbanism, the City aims to survive in an environment of arguably increasing entropy. As a secular rather than a theological construct, maybe it can employ rationality as a negentropic force.