2 Identifying the Needs of Young Children with Disabilities

Ensuring that young children with delays and disabilities are identified and given the same opportunities to succeed as their peers without disabilities is a goal that encompasses numerous entities, including public and private schools, hospitals, and even the US government.

The federal government recognizes that many individuals with disabilities, including young children, face discrimination and barriers that make being included as members of their community almost impossible. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), passed in 1990 and reauthorized in 2009, sets out to break down these barriers and guarantee that all people with disabilities can participate in American society.

Title III of the ADA prohibits child care providers from denying admission, terminating enrollment, or in any way discriminating against or excluding a child from a program because of a disability. The ADA also says that programs must make reasonable adaptations when necessary in order to accommodate the individual needs of each child (Child Care Law Center 2011).

Education laws, including specific special education laws, go beyond a child’s right to access educational programs and address how to meet the educational needs of children with disabilities so they can develop to their full potential.

Education for All Handicapped Children Act

In 1975, with the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142), the US government outlined the educational rights of children with disabilities and their families and allocated funds to states to provide children a free, appropriate public education and related services. Initially the law applied only to children and adults ages 3 through 21; those under the age of 3 were not eligible.

Amended in 1986 as Public Law 99-457, the law recognized the need to provide intervention services to infants and toddlers (from birth through age 2) who had a developmental delay or a diagnosed condition with a high probability of leading to a developmental delay. Provision of services for these children and their families was mandated, and states were given the option of providing services for infants and toddlers who were at risk for having a delay due to conditions such as low birth weight and abuse or neglect (Center for Parent Information and Resources 2014a).

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

In 2004, the law was reauthorized and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (Public Law 108-446). In 2011, the final set of regulations for Part C of IDEA, which pertained to infants and toddlers, was published. These regulations help states interpret the intentions of IDEA Part C and provide guidance for developing programs for infants and toddlers with delays or disabilities.

Part B of IDEA covers children and adults ages 3 through 21. Since services are administered differently under these two sections of the law, the processes of evaluating and providing services for infants and toddlers and for older children are discussed separately in this chapter.

Early Intervention: Birth Through Age 2

Early intervention is a system of services for infants and toddlers with developmental delays or disabilities and their families. Early intervention providers do not just work with the child; they also work closely with the family to support their child during everyday routines and activities.

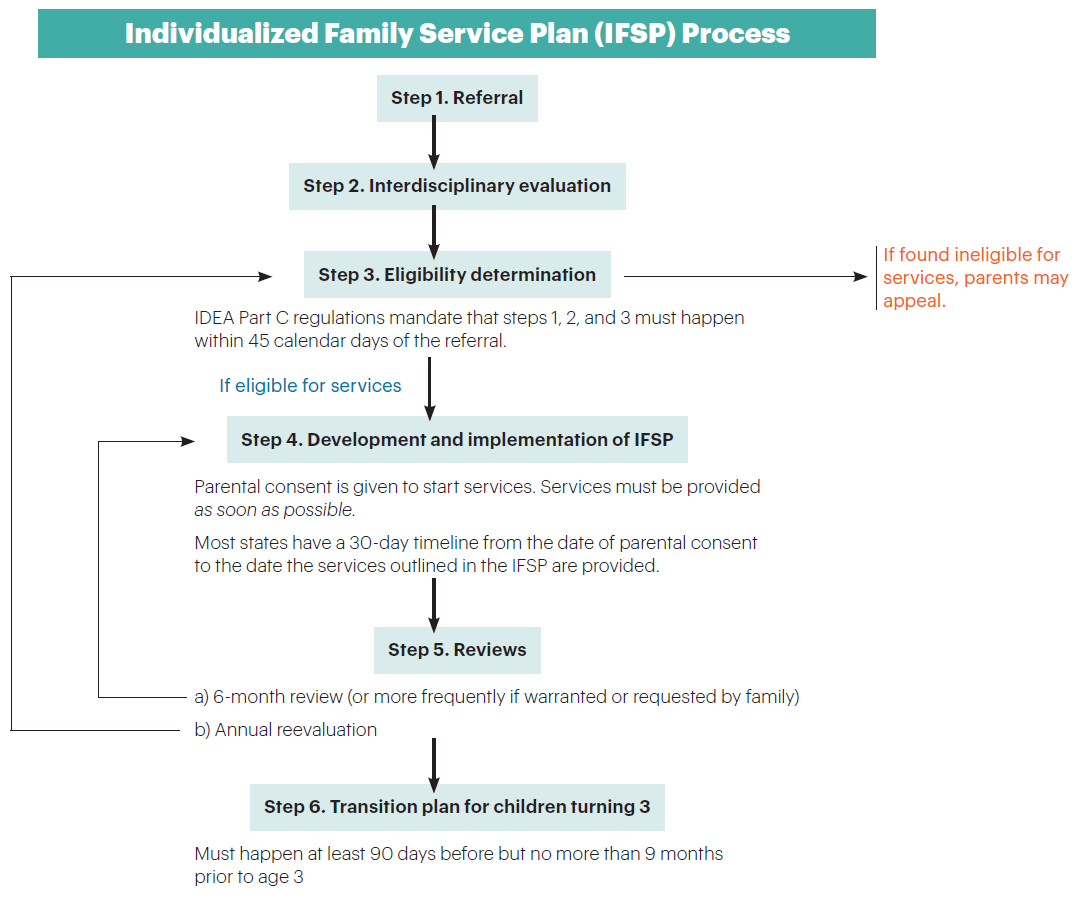

Each state administers its own early intervention program, so procedures for obtaining assistance, timelines for the steps in the process, and terminology vary from state to state and may even change over time. However, the basic steps outlined by the federal government are similar. These are discussed below and outlined in the figure shown here, “Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) Process.”

The Early Intervention Referral and Evaluation Process

1. Contacting the community early intervention system

In some states, the Department of Education and public schools coordinate the early intervention system, while in other states it is the Department of Health or another agency. To obtain contact information for early intervention services in their community, families can contact any medical doctor who treats infants and toddlers, such as a doctor in a local clinic or the pediatric department at a local hospital. Local public schools also may have this information for parents, even if the schools do not coordinate the system or a child is too young to attend school. Many states have a single point of entry for early intervention information and services, which means there is a single phone number to call for everyone who lives in a state.

When parents request early intervention services, either by contacting their state’s system directly or having a medical doctor or school staff member do so on their behalf, an early intervention representative asks the parents about their child’s development to decide the next steps. This is called a referral to early intervention. Before anyone from the early intervention system can evaluate or work with their child, the parents must give their written permission. If at any time the parents are uncomfortable or unhappy with the proceedings, they may revoke their permission. The early intervention program may conduct a screening to identify children who need additional evaluation to determine whether a disability or delay exists.

IDEA outlines the rights parents have to protect both them and their child throughout the evaluation process. Each state is required to provide parents with information about their rights in an easy-to-understand format in the family’s home language. IDEA regulations can be confusing for families to understand, so the law mandates that all families are entitled to a service coordinator to assist them in accessing the services and supports they need, including providing information about their rights.

2. Conducting an evaluation for early intervention services

A team of professionals who specialize in working with infants and toddlers evaluate the child to determine the child’s current developmental functioning and the existence of a disability or delay. The members of this team—known as an interdisciplinary team—may evaluate the child together or individually, and the parents are an integral part of the process since they know their child best. Team members’ areas of expertise vary according to the family’s and/or teacher’s concerns about the child. For example, if parents are concerned that their child is not speaking, a person with expertise in language development, such as a speech-language therapist, will be on the team. In addition to talking with the family—and perhaps other individuals who care for the child on a regular basis, such as child care providers or extended family members—the team members observe the child as she plays or completes tasks.

During an evaluation, the team assesses a child’s functioning in five areas, or domains, of development: physical, cognitive, communication, social and emotional, and adaptive. Here are some things the team may look for in each area.

Physical development: the child’s hearing, vision, and response to stimuli, as well as how he moves his arms and legs (large motor skills) and fingers and hands (small motor skills)

Infants: Depending on how old the baby is, the team may look to see if he holds his head up by himself, if he is crawling, and if he can pick up small objects (toys or food).

Toddlers: The team might observe how the child walks, runs, or generally gets around. They may watch to see if she can use a fork or spoon to feed herself or manipulate small toys. They may ask if the child is very sensitive or has a very strong dislike for the taste or texture of certain foods or the feel of certain clothing or material.

Cognitive development: the way infants and toddlers learn to understand the world around them

Infants: The team may look to see if the infant recognizes a familiar caregiver or pays attention to the faces of people and visually explores her surroundings.

Toddlers: The team may look to see if the child recognizes familiar or favorite objects in his environment (such as asking “Where’s the doggy?” if the child is being evaluated at home and the family dog is present). The team may also watch how the child plays with both familiar and new toys.

Communication development: the ways infants and toddlers express themselves to make their wants and needs known, as well as how well they understand what other people are saying

Infants: The team may look to see if the infant babbles and responds to his own name. With an older infant, they may watch for the child to use gestures to communicate, such as pointing to objects in the environment or shaking his head no.

Toddlers: The team may look to see if the toddler uses some words or sentences or can name familiar objects.

Social and emotional development: how the infant or toddler reacts to her own needs, the environment, and other people

Infants: The team may look to see if the infant smiles at or is easily comforted by a known caregiver. The team may also look at how the infant reacts to strangers.

Toddlers: The team may look to see if the toddler is interested in other children, imitates what other people do, and uses her parent as a safe base from which to explore her environment. The team may ask about temper tantrums and what they look like in this child if they do not observe this behavior during the assessment.

Adaptive development: the degree to which the infant or toddler assists with or completes self-help skills

Infants: The team may look to see if the infant can hold his own bottle or drink from a cup if age appropriate.

Toddlers: The team may look to see how independent the toddler is with tasks like dressing and eating by himself. The team may also ask about toilet training, bathing, and tooth brushing.

Each area of development is equally important, and although they may be evaluated separately, the areas overlap as children develop. For example, as children explore the world around them, they develop physically as well as socially and cognitively. Delays or deficits in one developmental area impact other areas.

In many states, children with specific physical or medical issues that are identified by a doctor and have a strong likelihood of leading to a delay in development are automatically eligible for early intervention services without any additional evaluations. Each state publishes a list of these conditions.

3. Determining eligibility for services

The parents and the interdisciplinary team members who evaluate the child hold an eligibility meeting to go over the results of the evaluation and decide whether the infant or toddler meets the federal and state criteria for eligibility to receive early intervention services. Other individuals may be present, such as the service coordinator and teachers or therapists who are or may be providing services. Parents are encouraged to invite other members of their family to the meeting, and they may bring an advocate to help interpret the evaluation results.

If the team determines that the child is eligible for early intervention services, they develop an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP).

4. Writing and implementing the Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP)

Early intervention focuses on family-centered intervention processes designed to help infants and toddlers who have delays or disabilities and to support the whole family. The philosophy behind these services is that the family is the child’s first teacher and greatest resource, so supporting the family as well as the child is critical to the child’s success. For example, an infant may have low muscle tone (hypotonia) and have difficulty holding his neck up independently. If the interdisciplinary team finds the child eligible for physical therapy, a physical therapist would work with the family to find positions for breastfeeding or bottle feeding that support the child and help him develop better muscle tone. As the child gets older, the therapist might work with the family as he learns to walk independently. Early intervention services are designed as a partnership to meet families’ needs and help parents and other caregivers support children’s development.

In addition to educational services, children may require other supports and services to meet some developmental milestones. Here are some of the most common therapies young children with disabilities receive:

Physical therapy. A physical therapist (PT) provides expertise in developing large motor skills, balance, coordination, and other skills so children can move as independently as possible.

Occupational therapy. An occupational therapist (OT) provides expertise in developing small motor skills so children can become more independent in self-care routines (eating, dressing, using utensils), manipulating objects (assembling puzzles, stringing beads), using tools like scissors and pencils, and playing with peers. An OT might also work with a child who has sensory processing issues (discussed in Chapter 11).

Speech-language therapy. A speech-language therapist (SLP) provides expertise in developing speech and language skills so children can develop both expressive and receptive vocabularies to interact with peers and adults and participate in learning activities.

What Is Included in an IFSP?

The IFSP form varies from state to state, but it must include the following:

• The child’s present levels of functioning and need in the areas of physical, cognitive (thinking), communication, social and emotional, and adaptive development

• Family information, including the family’s resources, priorities, and concerns

• The major results or outcomes expected to be achieved for the child and family

• The specific early intervention services the child will receive

• Where in the natural environment (e.g., home, community) the services will be provided. If the services will not be provided in the natural environment, the IFSP must include a statement justifying this decision.

• When and where the child will receive services

• The number of days or sessions the child will receive each service and how long each session will last

• Who will pay for the services

• The name of the service coordinator overseeing the implementation of the IFSP

• The steps to be taken to support the child’s transition out of early intervention and into another program when the time comes

The IFSP may also identify services the family is interested in, such as financial information or information about raising a child with a disability.

Adapted from “Writing the IFSP for Your Child” (Center for Parent Information and Resources 2016b).

Intervention is planned with the family and laid out in the IFSP. The IFSP identifies appropriate services that the child and family may be eligible for, such as physical, occupational, and/or speech therapy. The service coordinator helps families arrange for and manage various service providers or agencies.

Early intervention services are provided in the natural environment, which refers to whatever setting the child would typically be in if she did not have a disability, such as the family’s home or a child care program. In other words, the child does not have to go to a doctor’s office, hospital, or school to receive services. This allows a child’s family or other caregivers to learn how to integrate therapy strategies in their day-to-day routines.

Once parents consent to start implementing the IFSP, all supports and services must begin in a timely manner, usually within 30 calendar days of being agreed upon. These supports and services occur on a regular schedule based on what was agreed upon in the IFSP.

5. Reviewing the IFSP

The IFSP must be reviewed regularly to make sure that an infant or toddler is making progress and getting the services she needs. States are required under IDEA Part C to evaluate the IFSP once a year and review the document with the family every six months to make any needed changes. However, parents may request additional reviews from their service coordinator at any time.

6. Transitioning to special education at age 3

Children receive early intervention services through age 2 unless state law allows an extension of these services (Center for Parent Information and Resources 2014a). When early intervention ends, the child may transition to school-age services provided by the local public school district. The interdisciplinary team, along with the child’s family, evaluates and develops an Individualized Education Program (IEP) under IDEA Part B. Transition is a process in early intervention, and it is just as much a transition out of early intervention as it is a transition to public school preschool services. Each state has different criteria for IEP eligibility under IDEA Part B than for eligibility for an IFSP under IDEA Part C. The early intervention system takes the lead in this transition, and the service coordinator is responsible for assisting and supporting the family during this transition. The ultimate goal is a seamless transition of services between systems for the child and his family.

Who pays for early intervention?

Early intervention is partly funded by federal and state monies. The federal government pays 100 percent of the cost of the evaluations, developing the IFSP, and case management. For other services like speech therapy or physical therapy, each state has its own rules about payment, including cost-shares or co-payments (Center for Parent Information and Resources 2014b).

Special Education: Ages 3 Through 21

When children turn 3, the public school system generally takes the lead in offering supports and services for children with developmental delays and disabilities. The transition from early intervention to preschool may not be an easy one for some parents and children. They have new faces to become familiar with, and often they have built close, trusting relationships with early intervention professionals. Services may change with the transition, and the child may have a new location for services. Both the early intervention and the early childhood special education professionals must support and reassure families and children during this time.

While IDEA covers children from birth through age 21, some of the rules and processes are different when a child begins school-age services. While the IFSP and early intervention services focus on the child and family, Part B of IDEA provides an Individualized Education Program (IEP) that focuses on the child and her educational needs.

The Special Education Referral and Evaluation Process

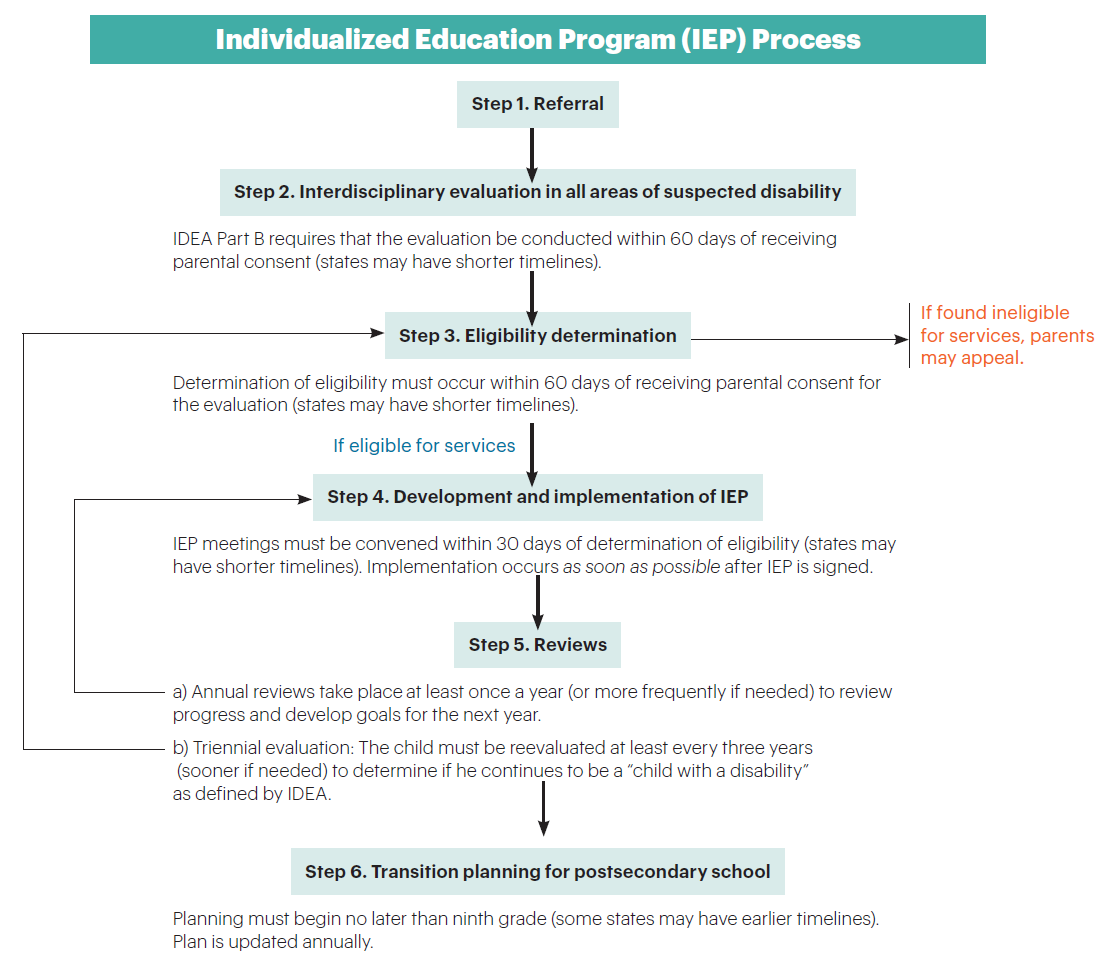

Each state administers its own IDEA Part B programs for children with suspected or identified disabilities. The Part B regulations outline eligibility requirements and procedures for seeking services, as well as the timelines for when the steps in the referral and evaluation processes must happen. As with the early intervention process, terminology varies from state to state and may change over time, but the basic steps are similar (see the figure below, “Individualized Education Program [IEP] Process”).

1. Making the referral

When an infant or toddler is receiving early intervention services, the state agency in charge of early intervention makes the referral to the local public school system when the child is about to turn 3. This is done to ensure continuity of service for the child. Service coordinators explain to families how this referral happens, what to expect, and their rights and responsibilities in this process.

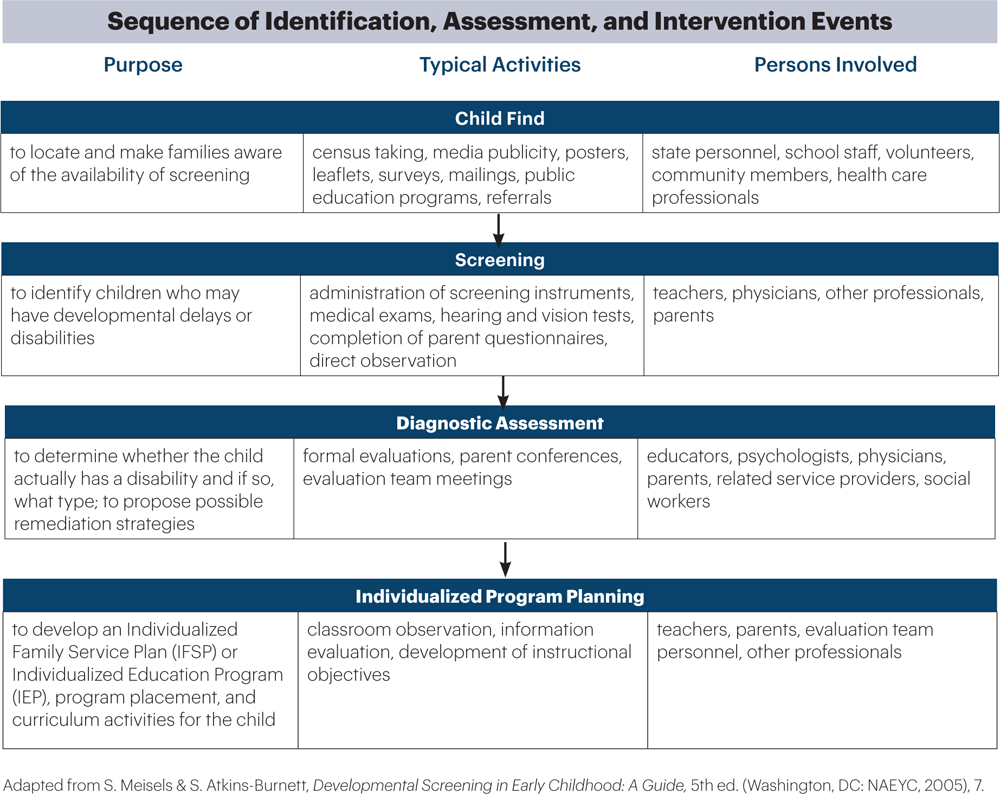

For a child who has not been in an early intervention program, most of the referrals for services come from the family. When a family is concerned about their preschooler’s development, they can contact their local public school and request assistance, even if the child is not yet enrolled in the school. Schools are required under Child Find, a system mandated by IDEA, to have policies in place to locate, identify, evaluate, and serve any child living in their communities who is suspected of having a disability and would benefit from the early intervention or special education services. As part of the Child Find process, a child may be screened to see whether she should be referred for an interdisciplinary evaluation.

Pediatricians and preschool programs can provide families with information about their state’s referral and evaluation process. Referrals from families should be made in writing, highlighting their concerns and requesting that the school evaluate their child for a disability. Once the school receives this written request for an evaluation, the school must follow timelines that are outlined in the state’s IDEA Part B regulations.

Other individuals, such as teachers or physicians, can also refer a child for a special education evaluation. However, no evaluation can occur without parental consent.

2. Conducting the evaluation

Evaluations to determine if the child has a disability are individualized and based on the child’s needs and the family’s concerns. The evaluation process must use valid, reliable assessments and assess all areas of suspected disability. As in the early intervention system, evaluations are completed by an interdisciplinary team of experts. The results of the evaluation are then used to determine if the child meets the state’s eligibility requirements for special education services.

3. Determining eligibility for services

The team that conducts the evaluation interprets the results to decide if the child meets the federal and state criteria to receive special education services. If the child is eligible, then the team and family work together to develop a program for the child. Should the team decide, based on evaluations, that the child does not have a disability and is not eligible to receive services, the process ends. If parents disagree with this decision, they have the right under IDEA to challenge it.

Disability Categories Under IDEA

The primary goal of IDEA is to ensure that special education and related services are available to children with disabilities in public schools. While each state sets its own eligibility criteria for these services, IDEA defines some specific disabilities that states use to help make their own definitions. Those disabilities identified in IDEA are

• Learning disability

• Intellectual disability (originally termed mental retardation in the law, but changed with the enactment of Rosa’s Law of 2011 [Public Law 111-256])

• Autism (now known under the broader term of autism spectrum disorder)

• Hearing impairment

• Visual impairment

• Orthopedic impairment (may be called physical disability)

• Other health impairment (such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, diabetes, asthma, epilepsy)

• Multiple disabilities

• Speech or language impairment

• Emotional disturbance (may be called behavior disorder or emotional disability)

• Deafness

• Deaf-blindness

• Traumatic brain injury

Developmental delay, a nonspecific category, may be used for children between the ages of 3 and 9 if they have delays in one or more areas of development.

Children are considered to have a disability if, after proper assessment, they meet the criteria for one of these disabilities and require special education or related services due to the disability (Center for Parent Information and Resources 2014a). Simply having a disability is not usually enough to be eligible; the disability must also affect the child’s educational performance. This does not mean that a child with a disability has to be failing in school to be eligible to receive services but that the disability impacts the child’s ability to learn.

4. Writing the Individualized Education Program (IEP)

Once a child is found eligible for services, an Individualized Education Program (IEP) is written by a team of people, including the parents, teacher(s), and some members of the evaluation team. The IEP specifies the following:

» The child’s Present Level of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance (PLAAFP), a description of the child’s current functioning in school or at home

» Individualized goals to be addressed in the following year

» Supports and services needed to access education, participate in instruction, and make progress toward the program’s standards and the IEP goals

The location where services will take place is also noted in the IEP. Placement must be in the least restrictive environment (LRE) for that child, meaning that to the maximum extent possible, the child is educated with his same-age peers who do not have disabilities. For many preschoolers with disabilities, this might mean they attend public school preschools, Head Start programs, or private preschool or child care programs. The LRE varies from child to child and may change over time. The IEP team may decide that a child with a disability will be best served in a classroom that is specifically designed to educate only students with disabilities, or that the best solution may be more than one placement, with part of the day spent in a classroom designed only for students with disabilities and the other part included in a classroom with their peers who do not have disabilities.

Although the decision is always individualized for each child, the goal is to provide children with as much access to programs with their peers as possible. Many professionals and families use the terms inclusion, full inclusion, or inclusion class to describe settings in which children with disabilities are educated alongside their same-age peers. IDEA uses the terms natural environment and least restrictive environment to describe the preferred settings for educating children with disabilities.

Once the IEP is written, families must give consent before it can take effect. In most states, to demonstrate this consent parents are required to sign a document stating that they are in agreement with what is written in the IEP and they want the IEP to be implemented. Parents should review the final copy of the IEP before they sign. If at any time the parents feel that a change in the IEP is warranted, they may request a new IEP meeting.

Inclusion is the practice of teaching young children with disabilities in the same classrooms with children their own age who do not have disabilities. While you may occasionally hear the older term mainstreaming to mean inclusion, the two are not interchangeable. Mainstreaming describes a child with a disability participating in a general education class for just part of the day or for specific activities.

5. Reviewing the IEP

The IEP team meets at least once a year to review a child’s IEP and identify the progress he is making toward his current goals. They also develop new IEP goals for the following year as well as decide what supports and services will be offered. Parents or school personnel can request additional meetings or amendments to the IEP if the child is not making progress toward his goals, or if the child is progressing better than expected and the goals must be adjusted to reflect this.

The IEP is not the curriculum

Many IEPs contain goals related to specific deficits and isolated skills a child needs to acquire. Unfortunately, these goals often become the de facto curriculum for the child. Keep in mind that a child’s IEP is intended as an addition to your program’s curriculum and standards. Use it as a tool to help you implement, not replace, the curriculum you use with all children.

6. Transition planning for postsecondary school

When the student is 16 years old, the IEP team, including the student and family, develops goals that will help prepare the student for adult life, including the skills needed to have a job, live independently, and be a productive member of society.

Partnering with Families Through the IFSP and IEP Processes

When Mrs. Lopez takes her just-turned-2 son, Sebastian, to his pediatrician, she mentions that both she and Sebastian’s child care teacher have noticed that Sebastian shows no interest in playing with or talking to other children. In fact, he shows little interest in other people at all and uses only a few words to communicate. He plays with cars by himself for long stretches of time, lining them all up in a row. Even when Mariana, his teacher, prompts Sebastian to play alongside another child, he continues to focus all his attention on his own play. During group times he sometimes participates in music activities, but otherwise he sits off by himself and looks away from the group. Mariana has suggested that Sebastian’s mother talk to his doctor.

Dr. Jimenez, the pediatrician, asks Mrs. Lopez several questions and decides to use the M-CHAT-R/F screening tool with Sebastian and Mrs. Lopez to get a better picture of what might be going on with Sebastian. The checklist indicates that he is at high risk for autism spectrum disorder. Dr. Jimenez feels that Sebastian might benefit from additional education options and suggests that Mrs. Lopez and her husband contact the early intervention program for an evaluation. After thinking about this, they decide to call.

Jill, the family’s new service coordinator, and a small team of professionals come to the Lopez house to play with Sebastian, evaluate his needs, talk to his parents, and answer their questions. Sebastian does not talk much while they are there, but he explores some of the toys they have brought. Mr. Lopez asks if the team is able to tell if his son has autism spectrum disorder. While the team members say they cannot diagnose Sebastian, they can share their findings with Dr. Jimenez so she can make a better determination about a diagnosis as he gets older.

At a meeting with Mr. and Mrs. Lopez to discuss the evaluation results, everyone agrees that Sebastian is eligible for early intervention services due to a delay in his ability to communicate as well as a delay in social and emotional development. They decide that he may benefit from speech therapy the most to help him learn to interact and communicate with others. Mariana and Rob, the speech therapist, meet with Mr. and Mrs. Lopez and Jill to develop an IFSP for Sebastian and outline the goals they will work on with him and his parents. Rob will come to the center twice a week to work on these goals in class, and Mrs. Lopez and Mariana will work together to carry over these goals at home and when Rob is not at the center.

For several months Rob works on getting Sebastian to play and interact with a few of the other children who crowd around Rob when he comes. Slowly Sebastian responds, and later Mariana notices that he has started to play alongside his classmates even when Rob isn’t there. Mr. and Mrs. Lopez are pleased with this progress, as is Mariana. Mariana decides to ask Rob for other strategies she can use in the classroom to build on Sebastian’s progress.

Parents and teachers can be strong partners in making sure that every child receives what she needs to be successful. NAEYC’s Code of Ethical Conduct and Statement of Commitment reminds early childhood educators that it is their ethical responsibility to children “to advocate for and ensure that all children, including those with special needs, have access to the support services needed to be successful” (2016, 2). You may be the first professional to recognize that a child has a delay in development or a disability, and you have a professional responsibility to discuss your concerns with the child’s family as soon as possible. Many parents rely on teachers for professional advice, and you need to be prepared to share your observations along with information the family can use to seek additional help if they wish. Advocating for children and becoming partners with parents is an essential role for every teacher, as is supporting families as they advocate for their own children.

Families and early childhood educators look at children through different lenses. Families see the child primarily at home in the context of everyday life with individuals he is very familiar with, and educators see the child primarily in programs in the context of early learning, alongside other children near the same age. Different environments, with different expectations for a child—no wonder parents and educators sometimes see children differently! Regularly communicating with a family about their child—his ups and downs, what he likes and doesn’t, how he interacts with others—gives everyone a better understanding of the child’s strengths and needs. It also assures the family that you care about their child and know him very well, and it helps to build their trust in you. Trust opens the door to being able to share your concerns with them.

Understanding Emotions

Discussing your concerns about a child’s development with a family is never easy, but it is important to help the child and family be able to access any supports or services they may be entitled to that will help the child be successful. When you share your concerns about a child, parents may have different reactions than you expect, including dismissing your observations or becoming angry, and they might need time to process this information and their feelings before moving forward (Ray, Pewitt-Kinder, & George 2009). Accept this, and avoid making judgmental statements. Make the effort to carefully listen to what they are saying, and encourage them to talk about their own concerns, doubts, and worries so you can understand their perspective.

Also, emphasize the child’s positive traits. Every child has strengths, and it is important to talk about what a child can do and not just focus on what she can’t do.

Being Prepared

Keep written documentation of your concerns about a child’s development, or the family’s concerns they share with you, in different situations and when different demands are put on the child. Having this information makes it easier for you, the family, and the child’s doctor to note patterns in the child’s development and see if he’s making progress. The information you provide may help the doctor diagnose a delay or a disability, and in turn, this diagnosis can help determine if the child is eligible for early intervention or special education services.

Tips for Communicating Your Concerns to Parents

Here are some things to consider as you prepare to talk with a child’s family:

» Understand the importance of time and place. Plan to talk with the family in person, making sure that all of you can set aside ample time for this conversation and that you have privacy. Do not try to have this conversation at drop-off or pickup time when families are in a rush, or during scheduled conferences when there is a narrow window of time and other parents are waiting for their meetings. Arrange a space to discuss the issues in private, without other adults or children being able to overhear or interrupt.

» Start with the positives. Every child has positive qualities—highlight them at the start of the conversation. Let the parent know what their child does well and encourage them to talk about what they see as their child’s strengths.

» Remember that words matter. Choose your words carefully, and avoid stating what you think may be wrong or your opinions about what the next steps should be. Discuss only what you actually observe and document in the classroom. Talk with the parents, not just to them. Let them ask as many questions as they need. And listen well.

» Offer additional information and support. Be prepared to help the parents with the next step in getting help for their child. Have information and resources available at the meeting so you can discuss them if the parents ask. Be respectful of the parents. Offer to help, but if the parents decline assistance at this time, do not force the issue. They may be ready to ask for help later, and then you can give it.

» Trust your instincts. While it is difficult to tell parents that their child may have a delay or disability, your professional instincts and experiences are a valuable resource. Trust them.

Despite their experience and expertise in the area of early childhood development, teachers need to be respectful of the family and their wishes, as well as careful not to share their opinions or unsolicited advice. Having concrete information about how their child is functioning in the classroom is essential for families to make a decision and seek more information about a potential delay or disability.