Iassume many of you are reading my book because you seriously need to make a food garden, starting just as soon as you can put some seeds or seedlings into the earth. I assume you can’t afford costly mistakes and wasted efforts. But these days, few people have had the good fortune to grow up on the land, so new vegetable gardeners have to catch up on some basics.

Every vegetable we eat was once a barely edible wild plant. As we humans improved that wild plant, its ability to compete was reduced.Vegetables have become oversized weaklings unable to best their ancestors, who remain the wiry guerilla fighters nature demands of its survivors.

A landscape may appear beautiful and serene, but look closely: a fierce battle is going on. Each plant is trying to overcome or outwit its neighbor, struggling to control light, moisture, and space.The scene seems peaceful only because the action is in slow motion and you are seeing the winners of the moment.

Our vegetables lack the survival skills wild plants still have.Wild plants know how to toughen up and conserve moisture when the soil gets dry; a moisture-stressed vegetable becomes nearly inedible.Wild plants will cope if they are put into the shade; veggie gardens must be grown in full sun or at least have the sun from 10 am until 4 pm.When the earth is infertile, wild plants adapt. Put a vegetable into the same circumstances and it usually just dies.Wild plants protect themselves from animals and insects with intensely bitter, unpleasant flavors. They make themselves poisonous. But we humans wish to eat sweet, pleasant-tasting food. So we must protect our relatively helpless veggies.

Wild plants usually make thousands of tiny, hard seeds so that even if most of these seeds are eaten or, having fallen on hard times, die, at least a few will manage to start the next generation. But we must sow vegetable seeds in welcoming conditions where they will survive and grow.

Wild plants have leaves and stems filled with strong fibers that resist damage from wind and heavy rain.Their roots anchor the plant firmly. But we humans want to eat tender juicy leaves, stems, and roots. If a veggie garden bears the brunt of a gale, leaves will likely be shredded and many of the plants will be half-uprooted.Veggie gardens require sheltered spots.

Most wild plants grow a huge network of roots to aggressively mine the soil.These roots are formed at the expense of making leaves.This is a pro-survival trade-off. But humans usually want the tops to grow large and lush, and this can only be done at the expense of weakening the root system, a reverse trade-off.

Luther Burbank, the famous 19th-century plant breeder, suggested that when humans domesticated a wild species, it was as though we made an enduring contract reading something like this: You agree to be my plant and to let me change you into something I will like better than the way you are now. I, in turn, promise that instead of leaving you to struggle to survive, I will eliminate or greatly reduce the competition you face. I will put you into much better circumstances than you now find in nature — moister, looser, richer soil — and I will value your seeds and propagate them forever.With this contract in hand, we began to alter our plants, changing them into what we wanted. We encouraged them to make bigger, juicer leaves (lettuce, spinach); larger flowers (broccoli, cauliflower, globe artichokes); or fewer but fat, tender, more flavorsome seeds (beans, wheat). Domesticated plants have greatly enlarged the upper storage chamber of their root while reducing the extent of the deeper subsoil system (carrots, beets, parsnips, potatoes).We caused them to make much larger, better-tasting (and fewer) fruit with thinner skins and fewer seeds (tomato, chili, eggplant). Burbank also said that whatever we envisioned plants becoming, they did, changing themselves to please us because we humans had become their protectors.

Although it took thousands of years to breed the changes we made in our food crops, it wasn’t too hard to accomplish because domesticatable plants are like dogs wagging their tails, trying to please. Our main breeding technique has been to first bare and loosen the soil, then place our seeds far enough apart that the plants don’t compete too much with each other. In this circumstance our crop benefits from all the water, light, and soil nutrients it can use, and each plant has enough room to develop well. If we happen to put in too much seed and our crop is too crowded, competing with itself, we remove some of these plants. This is called thinning.We also eliminate any wild plants trying to sneak in. This is called weeding. And then we save seeds from those plants that most please us. This is plant breeding in a nutshell.

These few simple practices are almost all there is to agriculture or to vegetable gardening:We eliminate wild plants; put in the ones we want to grow; space our plants so that they aren’t overly competing with each other; keep the wild plants from taking over; make our garden soil more fertile and more moist than nature does.And then our gentled plants bless us by happily allowing us to eat them because they are confident we are going to carry on their progeny in the coming years.

Field crop or vegetable

“Field crops” include the cereal grains — wheat, rye, oats, and barley — as well as corn (maize), rice, sorghum, millet, quinoa, and amaranth; some varieties of beans and peas, usually the types grown for dry seed; and oilseeds such as flax, sunflower, sesame, poppy, and canola. A field crop can be productive in unfertilized, ordinary soil, but it does better when that soil has been improved. Heirloom varieties, bred before the use of chemical fertilizers, are especially good at growing in ordinary soil.

Vegetables are different. For thousands of years the kitchen garden has received the best of the family’s manures and lots of them. After millennia of coddling in highly improved conditions, few veggies thrive in ordinary soil.

Low-demand vegetables. Some vegetable species can still cope with soil of the sort that will grow field crops if the soil has been well loosened by spading or rototilling. Low-demand vegetables include carrots, parsnips, beets, endive/escarole, snap and climbing (French) beans, fava beans (broad beans), and garden peas (see the sidebar listing vegetables by the level of attention they require).However, when low-demand vegetables are given soil considerably more fertile than their minimum requirement, they become far more productive. Low-demand crops are capable of struggling along and usually will produce something edible even under poor conditions.

Vegetables by level of care needed

| Low Demand | Medium Demand | High Demand |

| Jerusalem artichoke | globe artichoke | asparagus |

| beans, peas | basil, cilantro (coriander) | Italian broccoli |

| beet | sprouting broccoli | Brussels sprouts (early) |

| burdock | Brussels sprouts (late) | Chinese cabbage |

| carrot | cabbage (large, late) | cabbage (small, early) |

| other chicories | cutting (seasoning) celery | cantaloupe/honeydew |

| collard greens | sweet corn | cauliflower |

| endive | ordinary cucumbers | celery/celeriac |

| escarole | eggplant (aubergine) | Asian cucumbers |

| fava beans | garlic | kohlrabi (spring) |

| herbs, most kinds | giant kohlrabi | leeks |

| kale | kohlrabi (autumn) | mustard greens (spring) |

| parsnip | lettuce | onions (bulbing) |

| southern peas | mustard greens (autumn) | peppers (large fruited) |

| rabb (rappini) | okra | spinach (spring) |

| rocket (arugula) | potato onions | turnips (spring) |

| salsify | topsetting onions | |

| scorzonia | parsley/root parsley | |

| French sorrel | peppers (small fruited) | |

| Swiss chard (silverbeet) | potatoes (sweet or "Irish") | |

| turnip greens | radish, salad and winter | |

| rutabaga (swede) | ||

| scallions (spring onions) | ||

| spinach (autumn) | ||

| squash (pumpkin), zucchini | ||

| tomatoes | ||

| turnips (autumn) | ||

| watermelon |

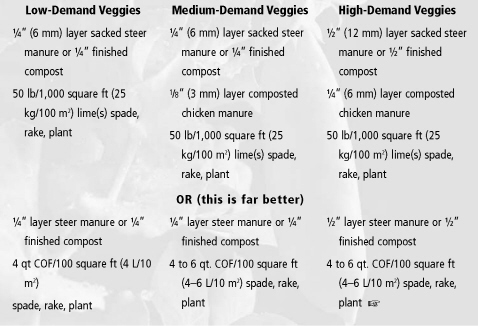

Medium-demand vegetables. These veggies need significantly enriched soil to thrive.This group includes lettuce, potatoes, tomatoes, corn, etc.What I consider the minimum enrichment for this group would be spading in a bit of agricultural lime plus either a half-inch-thick (12-millimeter) layer of well-rotted low-potency manure or else a quarter-inch-thick (6-millimeter) layer of well-made potent compost. But medium-demand vegetables will do enormously better when given soil considerably more fertile than their minimum requirement.

High-demand vegetables. These are sensitive, delicate species. High-demand vegetables usually will not thrive unless grown in light, loose, always moist soil that provides the highest level of nutrition. These vegetables become rather inedible unless they grow rapidly. In Chapter 9 I will discuss these vegetables one by one and will provide full details about how to cultivate them. If gardeners are not able to provide the nearly ideal conditions required by high-demand vegetables, they would be much better off not attempting to grow them.

Plants need minerals to construct their bodies. So do people. Human bodies need energy and enzymes, minerals, vitamins, amino acids, and, as research into nutrition continues, it seems an ever-extending list of other substances. Plants also need a wide assortment of organic chemicals produced by the soil ecology. These were named “phytamins” by the Russian researcher Krasil’nikov, who was, in my opinion, the world’s greatest soil microbiologist.The creation of phytamins is accomplished by microorganisms, and the process is still not well understood.

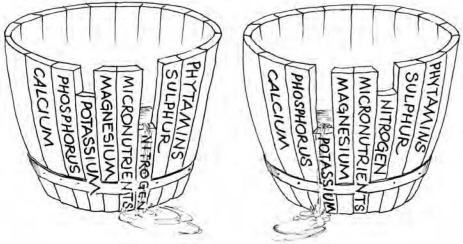

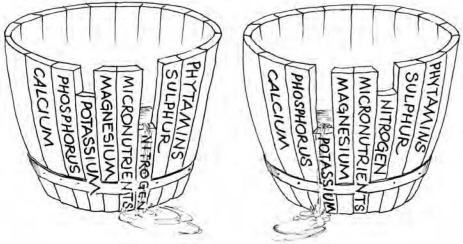

However, the mineral nutrition of plants is more straightforward. Agronomists are confident about which minerals are required, and in what proportions. As an example, most plants use a lot of calcium, but for every six to eight measures of calcium, they’ll also need one measure of magnesium, maybe a sixteenth measure of sulfur, and one ten-thousandth measure of boron. If they have heaps of calcium but are short of magnesium, then they won’t be able to grow any more than the amount allowed by the quantity of magnesium they’ve got. If they have adequate calcium, magnesium, and sulfur, all in the right proportions for ideal growth, but are desperately short of boron, then they will grow as poorly as though they were short of calcium and magnesium and sulfur.

Figure 2.1: Each stave in the barrel represents a different plant nutrient in soil. The ones at their full height are in full supply. The barrel at the left illustrates a soil in which the greatest deficiency is of nitrogen; plants will grow no better than the level of nitrogen. The barrel on the right shows that soil after nitrogen has been added. Now the most limiting deficient nutrient is potassium. The plants will grow no better than the level of potassium permits.

According to Dr.William Albrecht, chairman of the soils department of the University of Missouri during the 1940s and 1950s, the broadest differences in soils are caused by climate. Albrecht repeatedly pointed out that where it rains just barely enough for agriculture, the soils tend to be the richest and most balanced. Usually prairie grasses grow there. Where it rains a great deal, where vegetation looks lush and trees grow thickly, the soil is usually, overall,much less fertile and much less balanced. Sparsely grassed prairies once supported huge herds of healthy animals. Food from these fertile, balanced soils makes people healthy too. Before the trees were cleared, forested lands supported relatively few animals that tended to be smaller, less healthy, with a shorter lifespan than those on the prairies.

The best I can say about these well-rained-on soils is that they aren’t too bad for growing something.What do I mean by “not too bad”?

Before World War II most North Americans got most of their food from farms located not far from where they lived. As a result, differences in average human health due to local soil conditions were apparent. Albrecht provided this example: In 1940 the United States instituted a draft registration for military service. All young men had to report for a physical examination. In Missouri, the prairie soils in the northwest are far more fertile than the once thickly forested soils in the southeast of that state. If you draw a line across a map of Missouri from northwest to southeast, and test the soils all along that line, you’ll find that they get progressively poorer as you travel toward the Mississippi river, precisely as the amount of annual rainfall increases along that same line. Accordingly, approximately 200 men out of 1,000 examined from the northwest of Missouri were found to be unfit for military service, while 400 young men out of 1,000 from the southeast of the state were unfit. In the center of Missouri, about 300 per 1,000 young men were unfit.

Suppose the soil in your area contains abundant mineral nutrients in a near-perfect balance. In that case, the plants grown in your district will be healthy. If you take the manure from the animals eating that vegetation and/or take the vegetation itself and rot it down into compost, and then spread that compost or that manure atop your garden, what you have done is transported minerals in the right proportions to your garden and increased the overall level of minerals in the garden’s soil in the right proportions. The result is a much better garden producing the same highly nutritious food the surrounding land grows.

But suppose that the soils in your area do not contain a perfect balance of plant nutrients. This means the average vegetation in your area is not as healthy as it might be, and neither are the animals grazing on it.When you bring a load of that vegetation into your garden in the form of manure or compost, you are increasing the amount of organic matter in your soil, which is good. You are also increasing the amount of minerals in the soil, but you are amplifying the imbalances of those minerals. Importing large quantities of imbalanced organic matter often leads to trouble because rich and ideally balanced soils are rare, not common. When you depend on your garden to provide much of your food, your health will suffer to the degree that your soil is out of balance. Homesteaders mainly eating out of their gardens, even from organically grown gardens, have developed severe dental conditions or other health problems as a consequence of incorrect soil building.

If the soils around you are not rich and balanced, you should, if possible, take steps beyond ordinary manuring or composting to improve them.

Complete organic fertilizer

Because my garden supplies about half of my family’s yearly food intake, I maximize my vegetables’ nutritional quality. Based on considerable research, I formulated an organic soil amendment that is correct for almost any food garden. It is a complete, highly potent, and correctly balanced fertilizing mix made entirely of natural substances, a complete organic fertilizer, or COF. I use only COF and regular small additions of compost. Together they produce incredible results. I recommend this system to you as I’ve been recommending it in my gardening books for 20 years. No one has ever written back to me about COF saying anything but “Thank you, Steve.My garden has never grown so well; the plants have never been so large and healthy; the food never tasted so good.”

COF is always inexpensive judged by the results it produces, but it is only inexpensive in money terms if you buy the ingredients in bulk sacks from the right sources. Finding a proper supplier will take urban gardeners a bit of research. Farm and ranch stores and feed and grain dealers are the proper sources because most of the materials going into COF are used to feed livestock. If you should find COF ingredients at a typical garden shop, they will almost inevitably be offered in small quantities at prohibitively high prices per pound. If I were an urban gardener, I would visit the country once every year or two and stock up.

A fertilizer that puts the highest nutritional content into vegetables provides plant nutrients in the following proportions: about 5 percent nitrate-nitrogen (N), 5 percent phosphorus (P), and only 1 percent potassium (K, from kalium, its Latin name). It would also supply substantial and perfectly balanced amounts of calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg), and minute quantities of all the other essential mineral plant nutrients such as iodine, cobalt, manganese, boron, etc. The ideal fertilizer would release slowly, so the nutrients didn’t wash out of the topsoil with the first excessive irrigation or heavy rain. It would be a dry, odorless, finely powdered, completely organic material that would not burn leaves if sprinkled on them and would not poison plants or soil life if somewhat overapplied. All this accurately describes COF.

You could sizably increase bulk yield by boosting the amount of potassium in garden soil higher than COF will, but the nutritional content of the veggies would decrease by just about as much as the yield went up. Most commercial growers, be they chemical or organic growers, push soil potassium to high levels for the sake of profit.But the higher bulk yield potas-siumtriggers is in the form of calories — starch and fiber — and not in the form of protein, vitamins, enzymes, and minerals, which we need a lot more from our food.

COF is concocted by the gardener. All materials are measured out by volume: that is by the scoop, bucketful, jar full, etc. Proportions varying plus or minus 10 percent of the targeted volume will work out to be exact enough. Do not attempt to make this formula by weight.

I blend mine in a 20-quart (20-liter) white plastic bucket using an old 1-quart (1-liter) saucepan for a measuring scoop. I make 7 to 14 quarts (7 to 14 liters) of COF at a time.The formula is shown in Figure 2.2.

Formula for complete organic fertilizer

Mix fairly uniformly in parts by volume:

4 parts any kind of seedmeal except coprameal

OR

3 parts any seedmeal except coprameal and 1 part “tankage” (sometimes called “blood-and-bone” or “meatmeal”). This higher-nitrogen option is slightly better for leafy crops in spring

OR

4 ½ parts less-potent coprameal, supplemented with 1 ½ parts tankage to boost the nitrogen content

BLEND WITH

¼ part ordinary agricultural lime, best finely ground

AND

¼ part gypsum (if you don’t use gypsum, double the quantity of agricultural lime)

AND

½ part dolomite lime

PLUS (for the best results)

1 part of any one of these phosphorus sources: finely ground rock phosphate (there are two equally useful kinds or rock phosphate, “hard” or “soft”), bonemeal, or high-phosphate guano ½ to 1 part kelpmeal or 1 part basalt dust

Figure 2.2

Seedmeal and the limes are the most important ingredients. These items alone will grow a great-looking garden. Gypsum is the least necessary kind of lime and is included because it also contains sulfur, a vital plant nutrient that occasionally is deficient in some soils. If gypsum should prove hard to find or seems too costly, don’t worry about it and double the quantity of inexpensive agricultural lime. If you can afford only one bag of lime, on most soils, in most circumstances, your best choice would be dolomite, which contains more or less equal parts of calcium and magnesium. You could also alternate agricultural lime and dolomite from year to year or bag to bag.

Guano, rock phosphate, bonemeal, and kelpmeal may seem costly or be hard to obtain, but including them adds considerable fortitude to the plants and greatly increases the nutritional content of your vegetables. Go as far down the list as you can afford to, but if you can’t find the more exotic materials toward the bottom of the list, I wouldn’t worry too much. However, if shortage of money is a concern that stops you from obtaining kelpmeal, rock dust, or a phosphate supplement, I suggest taking a hard look at your priorities. In my opinion, you can’t spend too much money creating maximum nutrition in your food; a dollar spent here saves several in terms of health costs of all sorts — and how do you place a money value on suffering?

Seedmeals. Seedmeals, a by-product of making vegetable oil, are mainly used as animal feed. They are made from soybeans, linseed, sunflowers, cottonseeds, canolaseed (rape), etc.When chemically analyzed, most seedmeals show a similar NPK content — about 6-4-2 — although coprameal (which is made from coconuts after the coconut oil is squeezed out and is used mainly for conditioning race horses) is about one third weaker in terms of NPK than the other seedmeals. Coprameal has a plus point, however: coconuts are almost inevitably grown without pesticides or chemical fertilizers.

The content of minor nutrients — calcium, magnesium, and trace nutrient minerals — varies quite a bit by kind and from purchase to purchase, depending mostly upon the soil quality that produced the oilseeds.Most farm soils are severely depleted, so most seedmeals in commercial trade are probably rather poor in terms of supplying nutrients other than NPK.And because seedmeals are intended as feed and not as fertilizer, they are labeled by their protein content, not by their content of NPK.The general rule is that for each 6 percent protein, you are getting about 1 percent nitrogen, so buy whichever type of seedmeal gives you the largest amount of protein for the least cost. Seedmeals are stable and will store for years if kept dry and protected from mice in a metal garbage can or empty oil drum with a tight lid.

Tankage. Also known as meatmeal, tankage is a product of the slaughterhouse. In the United States it is made up of the whole animal, minus the bones and fat, ground to a powder and dried. In Australia a similar product is called “blood and bone” and contains everything but the fats. Tankage has no odor as long as it is kept dry, and it produces no odor when spread on the earth as part of COF. I have no health concerns regarding meatmeal, and I’ve used it for more than 20 years. However, if you’re worried about disease and decide not to use tankage, the only consequence will be that your COF will be slightly lower in nitrates, requiring that you use a bit more of it to get the same growth response. The form of tankage I get now analyzes at 10-4-0.

Lime(s). There are three types of lime, which is ground, natural rock containing large amounts of calcium.“Agricultural lime” is relatively pure calcium carbonate. “Dolomitic lime” contains both calcium and magnesium carbonates, usually in more or less equal amounts. “Gypsum” is calcium sulfate. (Do not use quicklime, burnt lime, hydrated lime, or other chemically active “hot” limes.) If you have to choose only one kind, it probably should be dolomite, but you’d get a far better result using a mixture of the three types. These substances are not expensive if bought in large sacks from agricultural suppliers.

You may have read that the acidity or pH of soil should be corrected by liming. I suggest that you forget about pH. Liming to adjust soil pH may be useful in large-scale farming, but is not of concern in an organic garden. In fact, the whole concept of soil pH is controversial. (If you are interested in the debate, read the papers of William Albrecht cited in the Bibliography.) My conclusion on the subject is this: if a soil test shows your garden’s pH is low and you are advised to lime to correct it — don’t. Each year just add what I recommend in the sidebar “Soil improving in a nutshell”: compost/manure and 50 pounds of lime(s) per 1,000 square feet (25 kilograms per 100 square meters), or else COF. Over time the pH will correct itself, more because of the added organic matter than from adding calcium and/or magnesium. If your garden’s pH tests as acceptable, use my full recommendation in “Soil improving in a nutshell” anyway because vegetables still need calcium and magnesium as nutrients and in the right balance.

One final thing about limes. If you routinely garden with COF, there will no longer be any need to lime the garden. COF is formulated so that when used in the recommended amount, it automatically distributes about 50 pounds of lime(s) per 1,000 square feet per year.

Phosphate rock, bonemeal, or guano.All three of these boost the phosphorus level and (except bonemeal) are usually rich in trace elements. Seedmeals of all sorts once had quite a bit more phosphorus in them, but over the last 25 years their average phosphorus content has steadily decreased. Incidentally, a comparison of nutritional tables published by the USDA over the past 25 years (covered in the March 2001 issue of Life Extension Magazine) shows that the average nutritional content of vegetables has also declined about 25 to 33 percent across the board — all vegetables, all vitamins and minerals. This is one reason I grow my own.

Kelpmeal.Kelpmeal has become shockingly expensive, probably in response to environmental degradation, but one 55 pound (25 kilogram) sack mixed into COF will last the 2,000-square-foot (200-square-meter) gardener several years. Kelp supplies plants with some things nothing else will supply — a complete range of trace minerals plus growth regulators and natural hormones that act like plant vitamins, increasing resistance to cold, frost, and other stresses.The kelpmeal imported from Korea costs less than the meal imported from Norway, but as far as I know, kelp is kelp is kelp. So long as the sack isn’t half sand, the price difference is only the cost of labor and the exchange rate.

There is a way to economize with kelp. Instead of putting dry meal into the soil, you can spray a tea made with kelp on the leaves.This is called “foliar feeding.”There are prepared kelp teas, but you can also make your own. Foliar feeding is more time-consuming than mixing the kelp into COF, but I believe the practice has advantages beyond frugality. Since foliar feeding needs to be done at least every two weeks, the spraying gets the gardener walking among the plants, putting into practice the old saying that the best fertilizer of all is the feet of the gardener.

Some rock dusts are highly mineralized and contain a broad and complete range of minor plant nutrients. These may be substituted for kelpmeal. But I believe kelp is best.

Using complete organic fertilizer

Preplant. Before planting each crop, or at least once a year (best in spring), uniformly broadcast four to six quarts (four to six liters) of COF atop each 100 square feet (10 square meters) of raised bed or down each 50 feet (15 meters) of planting row in a band 12 to 18 inches (30 to 45 centimeters) wide. Blend the fertilizer in with hoe or spade. If, despite my soon-to-come advice to the contrary, you do not dig your garden, just spread it on top of everything. Soil animals will eat it and mix it in for you. If you’re making hills, mix an additional teacup of COF into each. This amount provides a degree of fertility sufficient for what I’ve classed as “low-demand” vegetables — like carrots, beets, parsley, beans, peas — to grow to their maximum potential. It is usually enough to adequately feed all “medium-demand” vegetables. If you’re using less-potent coprameal as the basis of your mixture, err on the side of generous application.

Side-dress medium- and high-demand vegetables. If you want maximum results, then, in addition to the basic soil-fertility-building steps, I suggest that a few weeks after seedlings have come up or been transplanted out, sprinkle small amounts of fertilizer around them, thinly covering the area that the root system will grow into during the next few weeks. As the plants grow, repeatedly side-dress them every three to four weeks, placing each dusting farther from the plants’ centers. Each side-dressing will require spreading more fertilizer than the previous one. As a rough guide to how much to use, side-dress about four to six additional quarts (four to six liters) per 100 square feet (10 square meters) of bed, in total, during a full crop cycle. If a side-dressing fails to increase the growth rate over the next few weeks, that lack of result indicates it wasn’t needed, so do it no more.

Figure 2.3: Side-dressing plants.

Chemical fertilizers

Concentrated sources of pure plant nutrients should come with a label warning about giving plants too much. That is one reason I don’t recommend the use of chemical fertilizers. It is too easy for the inexperienced gardener to cross the line between enough and too much.

Another word of warning: You can poison plants with chicken manure and with seedmeal, too. They are powerful but not nearly so dangerous as chemicals because they are slow to release their nutrient content.

Chemical fertilizers are too pure.Unless the manufacturer’s intention was to put in tiny amounts of numerous other essential minerals, the chemical sack won’t supply them.What is especially troublesome is that chemical fertilizers rarely have any calcium or magnesium in them. This is particularly true of inexpensive chemical blends, so-called complete chemical fertilizers like 16-16-16 or 20-20-20 or 10-20-16. They are entirely incomplete. They only supply nitrates, phosphorus, and potassium. Depending on how the fertilizer was concocted, there may also be plenty of sulfur (S) in them, but not necessarily. Plants do need NPK (and S), but they also need large amounts of calcium and magnesium, and a long list of other essential minerals in tiny traces. Plants lacking any essential nutrients are more easily attacked by insects and diseases, contain less nourishment for you, and often don’t grow as large or as fast as they might.

There is yet another negative to mention. All inexpensive chemical fertilizers dissolve quickly in soil. This usually results in a rapid boost in plant growth, followed five or six weeks later by a big sag, requiring yet another application. Should it rain hard enough for a fair amount of water to pass through the soil, then the chemicals already dissolved in the soil water may be transported as deeply into the earth as the water penetrates (this is called “leaching”), so deep that the plant’s roots can’t access it.With one heavy rain or one too-heavy watering, your topsoil goes from being fertile to infertile. The risk of leaching is especially great with soils that contain little or no clay.

Organic fertilizers, manures, and composts, on the other hand, release their nutrient content only as they decompose — as they are slowly broken down by the complex ecology of living creatures in the soil.The length of this process is determined by the soil temperature. The rate of decomposition roughly doubles for each 10°F (5°C) increase of soil temperature. Complete decomposition of COF takes around two months in warm soil. During that entire time, nutrients are steadily being released. Gardeners in hot climates (with warmer soils) will get a bigger result from smaller applications of less-potent organic materials. The result will last a shorter time, too, though.

Chemical fertilizers can be made to be “slow release,” but these sorts cost several times as much as the type that dissolves rapidly in water. Slow-release chemicals are used to grow highly valuable potted plants and other nursery stock. Seedmeals, naturally slow releasing, are cheaper.

Manures and simple fertilizers

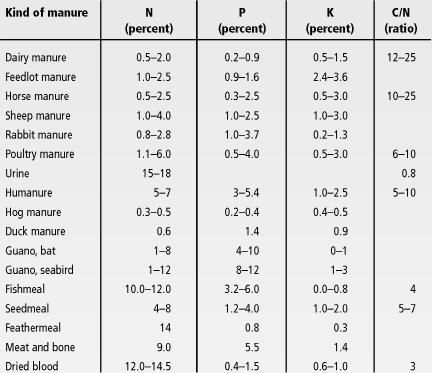

As mentioned earlier, spreading manure and compost made from vegetation in the district you live in is no guarantee of making garden soil that will produce the most highly nutritious vegetables possible. It will make nutritious food only if the soils around you are rich and balanced. Figure 2.4 shows the range of fertilizing values manures and simple fertilizers might have, depending on the nutrient balance in the feed the horse, cow, sheep, etc., was fed.

Please notice that horse manure can range from 0.5 percent nitrogen to 2.5 percent N. Cow manure can go as high as 2 percent, but may be as poor as 0.5 percent.The same spread occurs for phosphorus and potassium.There are two probable reasons for these wide ranges of value.One is that there is no telling how much, if any, bedding material was mixed into the samples being tested. More importantly, it is absolutely certain that what the animals ate varied greatly.

An acquaintance, I’ll call him Ken, grows a seemingly excellent garden using horse manure. (I’m somewhat skeptical because his children’s teeth and jawbones haven’t developed as one would expect for people growing up eating mainly organically grown vegetables). He uses nothing but what I consider enormous overdoses of horse manure and some agricultural lime. Others around me also use horse manure and get poor results.What is going on? Ken gets his manure at no cost from a nearby stable owned by a wealthy man who breeds, raises, and trains thoroughbred racehorses. These animals are fed like endurance athletes. Their hay is purchased from carefully selected fields, grown by knowledgeable farmers who know exactly when to cut it for the highest protein content and how to dry it so as to preserve the value. These horses are also given a broad range of protein, vitamin, and mineral supplements, including oilseed meals and abundant kelpmeal. Is it any wonder this manure grows stuff, even if Ken is using too much and throwing his soil out of chemical balance?

Fertilizing values of manures and simple fertilizers

NOTE: These figures were gathered over many years from numerous sources. Iwould be dubious about any row showing a single figure. If Iam told that duck manure has 0.6 percent nitrogen, Idon’t believe it. If Iam told it has from 0.4 to 1.3 percent nitrogen, I believe I’m being told the possible range for duck manure, at least as so far discovered. The extraordinary range in guanos is because some are fresh deposits and some are ancient fossilized rock-like materials that have lost all or virtually all their nitrogen.

Figure 2.4

Another neighbor sells horse manure from three sorry-looking nags loafing in her back pasture. The vegetation on their compacted, scabby field is pathetic despite all the horse urine the pasture receives. Because there is so little grass coming from that field, she has to buy most of the horses’ food. She feeds mainly local grass hay of a quality so low that the racehorse breeder I mentioned wouldn’t use it for anything but bedding straw.The manure makes rose bushes, low-demand plants, grow a little better.

My point? It is not easy to obtain manure that you can be confident about — that you can be sure will grow a great garden and produce highly nutritious food. That’s why I recommend using only the minimum amount of manure necessary to supply the soil ecology’s requirement for organic matter and suggest using COF to supply the plant’s requirement for nutrients.

Some of my readers will be growing a food garden without much money to spend on it. Some may not have access to free or almost free manure (except humanure). Some may not have the means to haul enough animal manure or materials to make an adequate amount of compost. Some will be more affluent; to them the idea of spending five or ten cents to grow a dollar’s worth of food will seem entirely reasonable and doable. Because of this range of readers, I will suggest a sequence of gradient steps instead of describing only one approach to increasing soil fertility. By gradient, I mean that each step is a step up and will give you a better result.

No soil improvers. If all I could manage to do with a piece of ground was spade it up, keep the weeds hoed out, and hope for the best, then all I would attempt there would be low-demand crops. Frankly, I can’t envision people in this situation unless they are starting a new garden without the first completed compost heap and cannot face the thought of using humanure.

Insufficient soil improvers available. Soil improvement materials were always scarce for Native American gardeners. Their approach, and a wise one it was: concentrate what fertilizer they could get into hills. Usually several plants were grown on each fertilized hill.The word “hill” in this case does not mean a high mound; it is a low broad bump about 18 inches (45 centimeters) in diameter that is deeply dug up and into which fertilizer is mixed. For Native Americans the fertilizer was often a buried bony “trash” fish that weighed at least one pound (500 grams). I expect the Native American garden was also used as the family latrine and as the burial yard for slaughtering waste, dead dogs, and other small animals, with each deposit making a hill.

These days, hills might be fertilized by roadkill or a quart (liter) of strong composted chicken manure and a few tablespoonfuls of agricultural lime.Used that frugally, one bag of chicken manure might fertilize quite a few hills, thus producing an enormous amount of food compared to the cost of the manure. If I had to fertilize hills with raw manure, I’d give the hill at least a month to mellow before sowing seeds. If I were collecting raw manure, I’d also try to collect urine and pour a pint or two into each hill.

A garden grown this way usually concentrates on raising large-sized low-or medium-demand vegetables such as squash or tomato vines. Such a hill could also grow a couple of corn plants, a cucumber vine, or a few kale or collard plants. The hills are always separated by about four feet (just over a meter) from center to center. I am guessing about this next statement of mine — it is based on only one reference in a document — but I suspect that the Native Americans east of the Mississippi, lacking steel shovels, did not dig up the ground between the hills. Instead they kept it under a permanent leaf mulch, bringing in loads of forest duff and spreading it between the hills.

Minimally sufficient soil improvers available. The next step up in both effort and cost would be to make highly fertile hills as before, but also to dig up the soil between the hills and fertilize it less intensely than you do the hills.This means the plants on those hills could more effectively extend root systems and find more nutrition beyond the hills they start out in.Gardening this way naturally leads into forming wide beds or wide rows for small plants while making extra fertile spots in these beds or rows for individual large plants.

In climates where there is good rainfall during the growing season, such as east of the 98th meridian in the United States, gardeners should spread agricultural lime (or for an even better nutritional outcome, a mixture of half agricultural lime and half dolomite lime) at a (combined) rate of 50 pounds per 1,000 square feet (25 kilograms per 100 square meters) before spading the garden.You don’t need a soil test for this step; light liming is always a safe and productive thing to do as long as your climate is humid enough to grow a lush forest. If the climate is semi-arid, the soil likely won’t need more calcium. Adding needed lime will greatly increase the health of your plants and boost the overall output and nutritional quality of all the food you are growing.Agricultural lime will especially make everything in the cabbage family grow better. If your soil is a bit short of magnesium, dolomite lime contains enough calcium to help the cabbages,while the magnesium it contains will make most of your vegetables taste a lot sweeter.

If your soil already has sufficient calcium and magnesium, the small amount I am suggesting you add won’t throw things out of balance. Finding out by soil test if a veggie garden needs more calcium and magnesium is usually a waste of money.An accurate and meaningfully interpreted soil test will cost far more than a little lime.However, for a farmer with a large area to manage, a proper soil test is a relatively small outlay compared to the cost of putting unnecessary lime (or other things) into many acres.

Spread lime once a year, either in spring or in autumn.Uniformly distributing 50 pounds of lime(s) per 1,000 square feet is quite difficult because it makes an incredibly spotty dusting. Spreading more, say 100 pounds per 1,000 square feet, which amounts to two tons per acre, is a lot easier, but even when the application goes up above three tons per acre, you barely turn the soil white with lime dust.However, spreading more than one ton per acre can be dangerous; over-liming ruins plant growth for years afterward. Regrettably, I’ve done it; don’t you do it, too. As my father said, the cheapest experience you can get comes secondhand — if you’ll buy it.

There are a few soils (usually clays in arid places) that need gypsum and do not receive much benefit from agricultural lime. There are also a few soils that need to avoid additional magnesium entirely because they already have too much of it, verging on magnesium toxicity (your local agricultural extension service will know if there are such soils in the area). But if you live where dense forests grow naturally and where it rains more than 30 inches (75 centimeters) per year, you probably have nothing about liming to be concerned about except making sure you don’t overdo it.

Another equally useful step is to minimally cover the entire garden with manure or compost at least a quarter inch (six millimeters) deep, and preferably double that depth, before spading it up. If I did not have enough well-decomposed ruminant manure or compost to cover the entire garden, I would manure whatever part of the area I could and use that area for growing both low- and medium-demand veggies. I could also attempt low-demand vegetables on those areas that I limed but did not manure; if the soil is naturally fairly fertile, the unmanured soil might still grow something useful. A somewhat better approach in an ongoing garden would be to grow low-demand vegetables on the ground that had been given manure or compost the previous year because some of that added fertility will still be in the soil the next growing season.

Soil improving in a nutshell

You will almost certainly have a reasonably productive garden if once a year (usually in spring), before planting crops, you spread and dig in the following materials for the type of vegetables you are growing.

These recommendations are minimums for growing low-, medium-, and high-demand vegetables on all soil types except heavy clays. Excessive liming can be harmful to soil. Do not use more than I recommend. COF is potent! Use no more than recommended here. However, it is always wise to exceed the amounts of manure and compost I suggest in this table by half again or double if you can afford to. No matter how much organic matter you may have available, do not apply more than double the amount recommended here or you’ll risk unbalancing your soil’s mineral content. If you think your vegetables aren’t growing well enough, do not remedy that with more manure or compost; fix it with COF.

Steer manure: Sacked steer manure is commonly heaped in front of supermarkets in springtime at a relatively low price per bag. However, this material may contain semi-decomposed sawdust and usually has little fertilizing value. It does feed soil microbes and improves soil structure, which helps roots breathe. And it has been at least partially composted; it is not raw manure. It is useful if not hugely overapplied.

Chicken manure: Chicken manure in sacks (which has been somewhat composted but is not labeled “compost”) or “chicken manure compost” is far better stuff than weak steer manure for fertilizing the veggie patch, but take care not to overuse it. The product I used to buy before I switched exclusively to COF was labeled with an NPK of 4-3-2, potent stuff.

For large plants I would make hills, as described in the previous section, giving each hill additional strong fertilizer. Agronomists call this practice “banding,” the idea being that as the young plants put out roots, they immediately discover a zone or band of highly fertile soil.This help gets them growing fast from the beginning so they outgrow environmental menaces. (One insect can take what seems a huge chunk out of a newly emerged seedling and may kill it from a single feeding. But once that plant becomes 50 times larger, the removal of the same single chunk seems but a tiny insult.) Later on, having had a good start, they’re more able to cope with less than ideal soil conditions.

Enough money. If money is not painfully short, I’d improve the soil for low-demand vegetables as though I were preparing for growing medium-demand ones. I’d prepare the soil for medium- and high-demand vegetables as though I were growing high-demand ones, and I’d also use COF instead of chicken manure compost. That’s what I do in my own garden.

Clay soils

The suggestions above apply if you’ve got a fairly workable soil — lots of sand or silt and not too much clay (for a discussion of soil content, see Chapter 6). If you have clay, though, you’ll have to do some extra soil preparation.

Clay soils do have some agricultural uses — if they drain well and aren’t the heaviest, most airless sorts of “gumbo” or “adobe,” they can be good for orchards and for permanent pastures. But no sensible farmer or market gardener would willingly use a clay soil to grow any crop that required plowing to make a seedbed — which is what veggie gardening is all about. Clay is incredibly difficult to work. If you dig it when it is even slightly too wet, it instantly forms rock-hard clods. It also gets rock-hard when dry, and if you have enough mechanical force at your disposal to plow or rototill it when too dry, it then forms dust. The first time this dust is rained on or irrigated, it slumps into an airless goo in which almost nothing will grow. There is only a short period during the drying down of a clay soil that it will form something resembling a seedbed when tilled.This fact means a clay garden can be mighty late to start in a wet spring. In Chapter 3 I describe a “ready-to-till” test you can use to determine when soil is at the right moisture to work. This test is essential when working clay.

Clay is heavy. Shovelful for shovelful it weighs twice as much as loam, so working clay soil exhausts the gardener. Even after it is tilled successfully (at the right moisture content), clay quickly settles into a hard mass, which makes it much more effort to hoe. As a result, it’s not easy to get weeds out of a clay garden. To top it off, clay tends to contain little air, so most vegetables don’t grow well in it.

Clay can be turned into something resembling a lighter soil by blending enough organic matter into it. Not the essential little bit that enlivens a soil containing less than half clay, but huge amounts, a layer several inches thick. But remedying clay this way is not wise for several reasons. First, because in the long run this practice is expensive. The high level of organic matter you must create to improve the structure of clay decomposes rapidly and requires replacement every year. The first year might take spading in a layer three to four inches (7.5 to 10 centimeters) thick to significantly open up a clay. In subsequent years you might only need to dig in a 1 ½ inch-thick (4-centimeter-thick) layer to maintain the benefit.That effort demands a lot of hauling.And spreading. And consumes your time spent making compost.And when all’s done, the remedial clay will never grow vegetables as well as a light soil will — never.

I am well aware of what garden magazines (and books) have said about the joys of turning any old clay pit into a Garden of Eatin’ by hauling and blending in enough composted organic matter. But please consider what I say in this book about the harmful nutritional consequences of unbalancing a soil after mixing too much organic matter into it. The quality of your garden’s nutritional output is your family’s health.

Remedying clay on the cheap. If your garden must be on a clay soil, and if you lack funds to do anything else and live where the native vegetation is a lush forest,my advice is this: before digging a new garden site for the first time, spread a layer of compost or well-rotted manure about one inch thick (2.5 centimeters) and spread 100 pounds of agricultural lime per 1,000 square feet (50 kilograms per 100 square meters). Add these large amounts only for the first year. If you live in a dry climate providing under 30 inches (75 centimeters) of rainfall a year (where soils may already contain significant levels of calcium and sometimes excessive magnesium, too) and have clay to deal with, I suggest that you consult with a local soil-testing service or agricultural agency before adding any forms of lime in excess of the minimal amounts in COF. You might be advised to use gypsum instead of lime.

A one-inch (2.5-centimeter) layer of decomposed organic matter blended into a shovel’s depth of clay is not enough to make it seem light and fluffy, but it is enough to make a decent garden.You’ll never grow prize-winning carrots, parsnips, or sweet potatoes in this soil, and it will never produce gigantic broccoli, but it will serve. In subsequent years you can manage your garden as I suggest for other soil types, but take extra care not to dig it when wet. And especially when working clay, if you want to end up with a reasonable seedbed after the first year, put your amendments of compost or manure into the surface with a rake after digging, as will be described in Chapter 3.

Chemically, clays act like discharged lead-acid batteries. They have the capacity to soak up huge quantities of plant nutrients. Until they have been brought close to “full charge,” they tend to withhold nutrients from your vegetables. I strongly suggest that gardeners with clay make and use COF, applying it at about 1 ½ times the usual rate for the first few years.

Remedying clay when you’re able to invest. Almost no one who considers a vegetable garden one of the most important things in life and has had the experience of trying to garden on clay would ever buy a home surrounded by clay soil unless there were some other compelling reasons. But if you are already located on clay, there is something you can do that is a lot cheaper than moving, something that will result in a garden nearly as good as one situated on a much lighter soil. Simply import a thick layer of loam topsoil and spread it above the clay.

I confess: I did this for my current garden. I live in an absolutely beautiful but simple home surrounded by six acres (2.5 hectares) of healthy native forest full of animal and bird life. It is on a steep sun-facing hillside with long views of a large river below us and of the mountains beyond seen through the trees. I love living here in the bush: I have no useless lawn to mow to please Everybody Else, and in the mornings I see numerous kangaroos grazing just outside my windows.

On my entire property there is only one area that is relatively flat and sunny enough to make a garden. And the soil there is a deep black clay. So I had many truckloads of topsoil dumped in a huge heap right in the center of the new garden site. I bought enough soil to cover all my beds (not the paths) nearly one foot (30 centimeters) thick. Next I erected a wildlife fence and then, with a wheelbarrow, began spreading that topsoil, creating one bed after another.What I ended up with is a garden where the topsoil is an easy-to-work loam, and what had been a clay topsoil became the subsoil.

I might mention that before covering the beds with topsoil, I limed, lightly manured, and rototilled the clay, thus accelerating the improvement of my subsoil by several years.Had I not done this laborious task, the clay would have loosened up anyway, but far more slowly. Eventually the worms would have transported humus into the clay, and leaching would have transported mineral nutrients into it. Eventually.

It cost me approximately $1,200 to have 120 cubic yards (100 cubic meters) of sandy loam topsoil delivered — a small investment, actually, when you consider the value of what I can grow with it.However, over the next few decades this investment will work out to be the least costly of all alternatives, and one that will pay large dividends for as long as I use the garden. Instead of being on the treadmill, having to haul and spread 20 to 25 cubic yards (15 to 20 cubic meters) of compost the first year to “build up”my clay into an inadequate imitation loam, and then another 10 to 15 or more yards (8 to 12 meters) every following year to maintain it in that condition, I now need only two or three cubic yards (1.5 to 2 cubic meters) a year to enliven my genuine loam topsoil. Because my soil has not been given too much organic matter, the nutritional qualities of my vegetables are the highest they can be. Because I am digging a light soil, I can work my garden early in spring when it is wet.

Because the soil is light, I don’t get tired from digging it and it forms a fine seedbed with little effort. The only crop in my entire garden that does not grow as well as I might hope is celery, which, to grow really well, requires a light loam soil at least three feet (one meter) deep.

Soil temperature and oxygen

Here’s something you probably don’t already know about plants.The business of construction, of growth, is mainly done at night. Plants store up energy by converting sunshine, water, and air into sugar during the daytime. They burn that sugar as energy to grow with during the night.

Assuming the plant lacks for nothing in the way of nutrition, moisture, etc., then the speed with which a plant grows is determined by temperature. For every 10°F (5°C) increase in temperature, the speed of growth doubles, meaning the size increases from 1 to 2, then to 4, and then 8, 16, 32, etc.When the nighttime temperature is much below 50°F (10°C), all biological chemical reactions, including growing, go on slowly; nothing much seems to happen. Even fruit won’t ripen much when the nights are chilly because ripening is just another form of growing. Let’s say that during a chilly evening when the temperature has dropped to 50°F at sundown, the plant will grow one size larger overnight. If the nighttime low is 60°F (15°C), the plant can grow two sizes larger. If the night is a warmer one, when the low is 70°F (21°C), the plant enlarges by four sizes overnight. On a steamy evening when people can hardly sleep and it is 80°F (26°C) at sunup, all other things being equal, the plants in the garden may have grown eight sizes overnight. That’s why on a hot midsummer’s night you can hear the corn growing.

This principle also applies to sprouting seeds, which is another growth process. Some kinds of vegetable seeds (spinach, mustard, radish) can sprout in chilly soils, though slowly, usually taking two weeks to emerge, where in warm earth they would be up and growing in four or five days. Others (melons, cucumbers, okra) need warm soils to germinate at all and either sprout quickly in warmth or rot in the earth if it is too chilly.

One of the most educational bits of equipment new gardeners can have is a soil thermometer. Watching it closely over a few springs allows them to grasp the connection between the daily weather, the rise and fall of soil temperature a few inches below the surface, and the resulting rate of seed sprouting and plant growth. It is not only air temperature and the amount of sunshine that determines how fast a plant grows. For the tops to grow, the roots have to grow, too. And, all things being equal, the speed at which roots grow is determined by the soil’s temperature.

TV documentaries and botany books all tell us that when plants use solar energy to make sugar, they take carbon dioxide from the air and break it down into oxygen (which they can breathe or release into the air) and carbon, which they combine with water into sugar. This is true. What books and movies don’t point out, though, is that, without sunlight, the plant can’t do photosynthesis and so has to breathe oxygen like any other living thing.

The roots do not conduct photosynthesis.And oxygen can’t be sent from the leaves to the roots. So the roots, being alive, need to breathe in oxygen all the time, and like other carbon burners on our planet, they breathe out carbon dioxide gas.How do they get oxygen? At a casual look, the soil might seem like a solid thing, but it is actually made of little particles that have spaces between them filled with either water or air.The larger the air-filled spaces are, the more freely air can move between the particles and the more freely the soil air, which gets thick with carbon dioxide exhaled by all the living things in it (including plant roots, soil animals, and microorganisms), can be exchanged with atmospheric air,which contains the normal amount of oxygen.The more oxygen the roots can get, the faster they can grow.Growth above ground matches what is happening below ground. If the roots are choked for lack of soil oxygen, even if there is otherwise plenty of fertility in the soil, the growth of the top will also be reduced.

One reason we dig before planting is to get more air into the soil, to fluff the earth up and temporarily create more air spaces in it. But within four to six weeks the soil will settle back to its natural degree of compaction. So plants grow faster for a month or so after spading, but then their growth slows down. Most vegetable crops occupy their beds for 12 or more weeks, and a few will grow on for five months or so, but you can’t spade up a bed after the plants are in and growing.There is a remedy:Digging in compost or manure loosens the texture of the soil far better, and for far longer, than digging alone will do.This better texture is called tilth, and the improvement lasts for a year or three, depending on how much manure/compost was dug in and how fast it rots away.

This chapter has provided the bare minimum of information and some basic techniques. If you knew nothing more than this, and if you spread manure and lime (or, better, manure and COF), dug the ground once a year, followed the vague instructions on the back of seed packets, put in some seedlings and a few seeds, hoed the weeds, and did a bit of thinning, you would have a productive garden. But there is quite a bit more to be known.

The next chapter will explain how you can use hand tools to work the soil more effectively, show you a better way to manure the ground in an ongoing garden so that your seeds will germinate more effectively, and describe a number of other techniques that will both save you time and make your efforts pay off better.